The U.S. Department of Defense is undergoing more than just a rebranding — it is being reshaped in appearance as well. “No more beards, no more dudes in dresses,” declared Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth on Sept. 30, flanked by the top brass of the armed forces. Donald Trump, for his part, warned that he would dismiss any general who failed to please him. On Sept. 27, the president ordered the army into Portland, Oregon, to “restore order,” defying local authorities in a manner already seen in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. Trump is redefining the role of the military in American life, renaming the Department of Defense and carrying out purges among generals. But while the president treats the military as a powerful instrument of domestic influence, public trust in the armed forces among ordinary Americans is plummeting.

Content

Army in the streets

“I need generals like Hitler’s”

Purges in the ranks

War on leaks

Naming the ship

The army in politics

Army in the streets

In 2020, during Donald Trump’s first term in the White House, a wave of protests swept the country under the slogan Black Lives Matter slogan, and the president threatened to send in the armed forces to disperse the demonstrations, which were indeed marred by violence in several notable instances. At the time, however, the Pentagon and senior military leaders resisted the move.

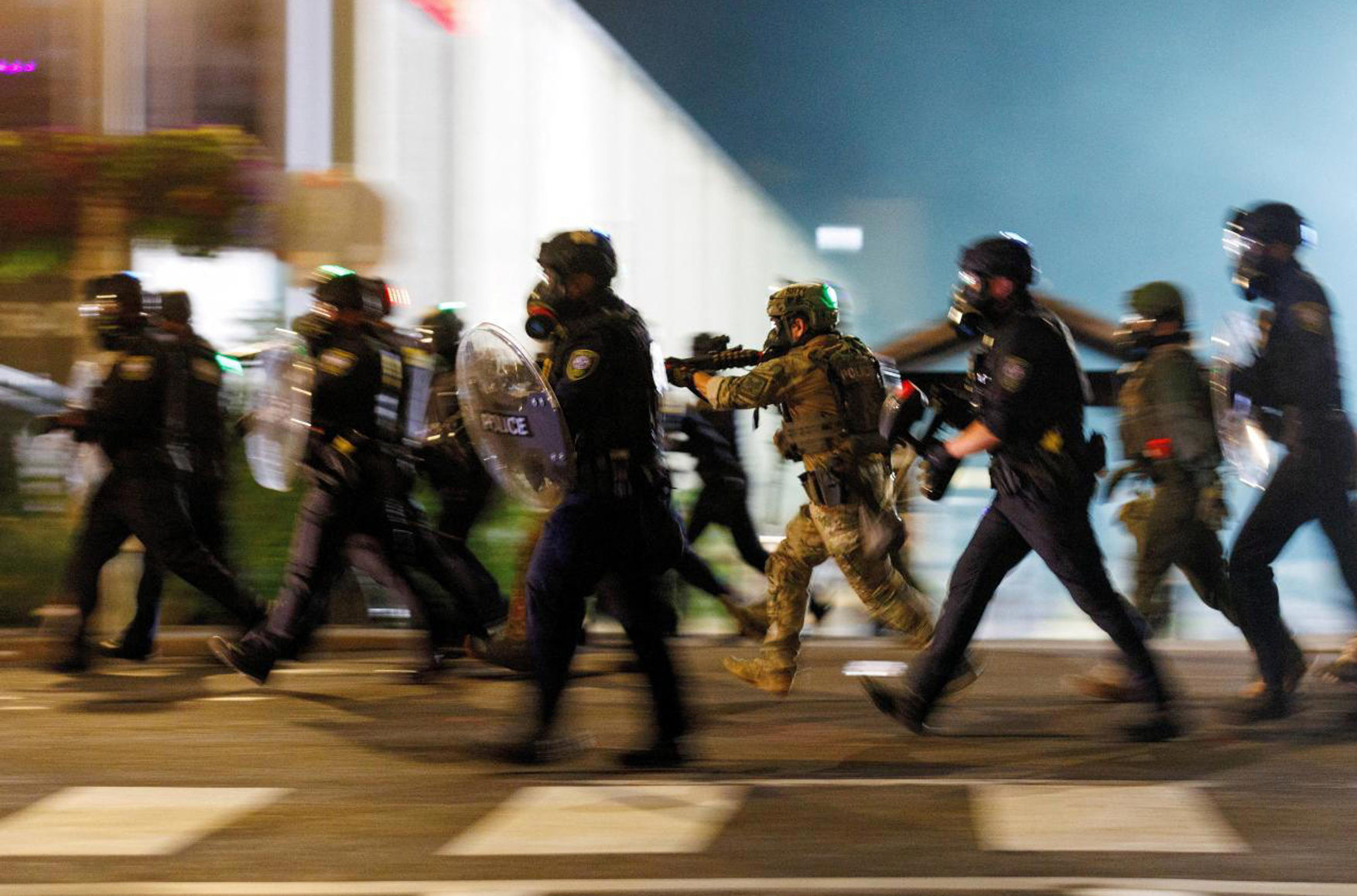

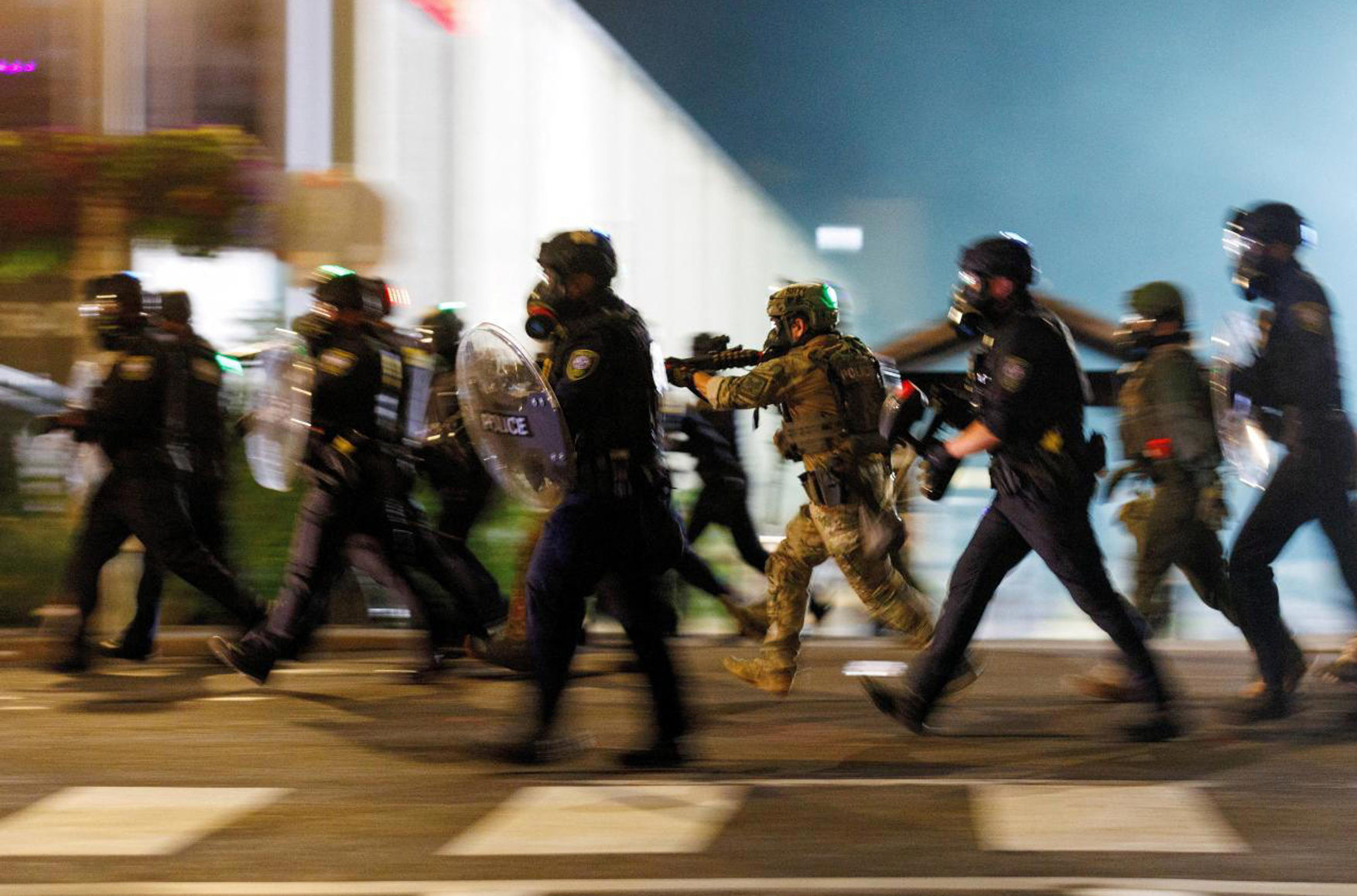

Now, however, there is little to restrain Trump. In June, he deployed more than 4,000 National Guard troops and an additional 700 Marines to Los Angeles after unrest erupted over raids by ICE. Masked officers staged dragnets outside supermarkets, roughly detaining Latinos and anyone else who did not speak English. Only about 10 percent of those arrested had a criminal record. The raids forced many migrants to stop going to work, costing the state an estimated 270,000 jobs.

Because of the National Guard raids, California lost about 270,000 jobs

The decision to deploy troops was made without consulting California’s Democratic governor, Gavin Newsom. Due to logistical problems, some of the service members who were ordered to cordon off federal buildings in downtown Los Angeles had nowhere to spend the night.

California authorities filed a lawsuit, accusing the White House of violating the 1878 Posse Comitatus Act, which prohibits the use of the military for law enforcement inside the country. In September, a federal district court in San Francisco agreed with those arguments and ruled the deployment unlawful, though that decision is now under appeal.

In early August, the National Guard was sent to the nation’s capital. Trump justified the move by citing the need to combat crime, undocumented immigration, and homelessness. Initially, 800 guardsmen were deployed to Washington, but the number later rose to 2,300 — with reinforcements coming from Republican-led states including Ohio, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. Alongside them, several hundred federal law enforcement officers began patrolling the streets, while the local police were placed under White House control.

By the end of August, the Trump administration had reported more than a thousand arrests and a 23% drop in violent crime compared to previous weeks. However, both local police and the FBI stated that violent crime in the city had already been at a record low before the National Guard was brought in. In the first half of 2025, Washington police reported crime falling another 26% compared to the same period a year earlier. The White House, however, insists that local police are falsifying statistics and concealing the true scale of lawlessness.

At the end of August, the Pentagon authorized National Guard troops to carry firearms while patrolling the city’s subway and streets, and some service members were assigned to improve the capital’s appearance — collecting trash, removing graffiti, and planting trees. Given that maintaining a military presence in Washington costs an extra $1 million per day, this can hardly be called an efficient use of funds.

The army’s presence in the capital sparked protests from local residents, who booed the troops and shouted insults at federal law enforcement officers. In one such incident, Justice Department employee Sean Dunn threw a sandwich at an ICE agent. Dunn was arrested and fired, and federal prosecutors attempted to charge him with assault, but a grand jury declined did not go along.

Dunn became one of the faces of the Washington protests. Soon posters appeared across the city depicting a man throwing a sandwich — including at Trump adviser Stephen Miller. In early September, tens of thousands joined a “We Are All D.C.” march demanding the withdrawal of troops, preservation of the city’s autonomy, and the granting of full statehood.

Polls show that only 38% of Americans — and just 17% of District of Columbia residents — supported the deployment of National Guard forces in the capital. As with the Los Angeles operation, city authorities are now seeking to challenge the White House’s decision in court.

American discontent with ICE actions is spilling over into protests

But that was far from the end of the story. At the end of August, Trump signed an order instructing the Pentagon to prepare specialized National Guard units that would be “specially trained and equipped to address issues of public order,” ready to assist law enforcement during riots and other incidents of unrest.

The president repeatedly threatened to send them to other major cities, including Chicago, New York, Baltimore, and Seattle. Polls show that nearly 60% of Americans oppose such measures, and Trump’s advisers warned that without the consent of Democratic governors, these deployments would be immediately challenged in court.

Nevertheless, on Sept. 16, Trump announced the deployment of National Guard troops and federal law enforcement officers to Memphis, the second-largest city in Tennessee. The state’s Republican governor, Bill Lee, endorsed the move and was present at the White House during the signing of the order. The city’s Democratic mayor, Paul Young, said the Guard would not help reduce crime in Memphis.

Trump called the crime rate in Memphis “one of the highest in the country” and claimed it was continuing to rise. In 2024, Memphis was indeed ranked the most dangerous of America’s large cities, recording 2,500 violent crimes per 100,000 residents. In 2023, the city registered 390 murders — the highest figure in recent years.

But as in many other major U.S. cities, overall crime in Memphis has been declining. Recently, the local police department reported that, during the first eight months of this year, crime fell to its lowest levels in 25 years, with homicides reaching a six-year low.

Then, on Sept. 27, Trump ordered Hegseth to send the army into what he called the “war-ravaged Portland,” Oregon, and to use “full force” to protect migrant detention centers from attacks by antifa, which the president had recently designated a terrorist organization. For several months, a few dozen demonstrators had been camping outside an ICE office, at times clashing with the federal officers trying to disperse them. Oregon Governor Tina Kotek and Portland Mayor Keith Wilson have both spoken out against sending troops into the city.

In comments to The New York Times, five retired generals who once commanded National Guard units noted that deploying the Guard domestically for law enforcement purposes was not only legally questionable but also damaging to troop morale and to the army’s image in the eyes of Americans. As Lieutenant General Russel Honoré, who led the Guard during the response to Hurricane Katrina, put it: “When things go bad, like at Kent State, it ends badly.” (He was referring to the May 4, 1970, protests at Kent State University in Ohio, where National Guard troops who were sent in to break up an anti–Vietnam War demonstration killed four people and wounded nine others.)

“I need generals like Hitler’s”

Trump’s troubled relationship with the military leadership dates back to his first term. After visiting France for Bastille Day in 2017, the president demanded a similar military parade in Washington. The armed forces, together with the capital’s mayor, talked him out of it, citing the cost and impracticality of such a spectacle. He only managed to bring the plan to life after returning to the White House in 2025, when the U.S. Army celebrated its 250th birthday.

Back in his first term, during the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, Trump pressed then–Defense Secretary Mark Esper and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Mark Milley to send in the military to break up demonstrations and asked whether troops could shoot protesters in the legs. On June 1 of that year, police acting on Trump’s orders dispersed demonstrators in downtown Washington so that the president could pose for photographs holding a Bible in front of a local church. Esper and Milley, who stood alongside Trump that day, later apologized, saying they had been misled about the nature of the event.

Before stepping down in 2023, Milley delivered an emotional farewell address reminding his fellow service members that their oath is to the U.S. Constitution, not to its leader: “We do not take an oath to a king, a queen, a tyrant, or a dictator, and we do not take an oath to a man who aspires to be a dictator. We do not take an oath to any one person. We take an oath to the Constitution and to the idea of America, and we are prepared to die defending it.” Many at the time saw the missive as being aimed at Donald Trump.

After leaving the military, Milley spoke candidly with journalist Bob Woodward, sharply criticizing Trump: “He is the most dangerous person ever. I had suspicions when I talked to you about his mental decline and so forth, but now I realize he’s a total fascist. He is now the most dangerous person to this country.”

After his resignation, General Mark Milley called Trump a “total fascist”

That description was echoed by retired General John Kelly, who served as Trump’s White House chief of staff from 2017 to 2019. When asked by reporters whether he saw fascist traits in Trump, Kelly replied: “Certainly the former president is in the far-right area, he’s certainly an authoritarian, admires people who are dictators — he has said that. So he certainly falls into the general definition of fascist, for sure”.

In another interview, Kelly recalled that Trump once asked him in frustration why American generals could not be like German military leaders. When Kelly asked if the President of the United States meant the generals under Bismarck, Trump replied that he was talking about Hitler’s top brass.

Kelly tried to push back, reminding the president that Germany’s military had made several attempts to overthrow Hitler, one of which culminated in an assassination attempt on the Führer. But Trump disagreed, insisting that “they were totally loyal to him.”

Ahead of the 2024 election, Trump was also criticized by the aforementioned Mark Esper. Commenting on Kelly’s remarks in an interview with CNN, the final Defense Secretary of Trump’s first term said the president did indeed “have fascist tendencies.” His predecessor at the Pentagon, General Jim Mattis, who resigned after Trump’s decision to withdraw U.S. troops from Syria and Afghanistan, had also been critical. In 2020, Mattis issued a statement calling Trump “the first president in my lifetime who does not try to unite the American people,” accusing him of mocking the Constitution via his threats to use the military to disperse protests.

Purges in the ranks

Upon returning to the White House in 2025, Trump endeavored to avoid repeating past mistakes by appointing Fox News host Pete Hegseth, a National Guard veteran who attained the rank of Major, as Secretary of Defense. During Senate hearings, Hegseth faced accusations of sexual harassment, drinking on the job, and misusing funds from a nonprofit. Nevertheless, after the Senate split 50-50 on his confirmation, Hegseth was sworn in thanks to the tiebreaking vote from Vice President J.D. Vance.

Once at the helm in the Pentagon, Hegseth immediately began dismissing senior officers suspected of disloyalty to Trump. Among those ousted were Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Charles Brown, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Lisa Franchetti, Coast Guard Commandant Admiral Linda Fagan, and Air Force Vice Chief of Staff General James Slife. Hegseth had previously accused some of them of being appointed thanks to racial and gender quotas.

Once at the helm of the Pentagon, Hegseth immediately began dismissing senior officers suspected of disloyalty to Trump

In August, he also fired the head of the Defense Intelligence Agency, Lt. Gen. Jeffrey Kruse. In June, the agency had prepared a preliminary report on U.S. strikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities, and the document, later leaked to the press, stated that the attacks had only delayed Iran’s nuclear program by a few months — contradicting the White House’s official claim of complete destruction of the sites. In addition to Kruse, Hegseth dismissed Navy Reserve chief Vice Adm. Nancy Lacore and Navy SEAL officer Rear Adm. Milton Sands, who oversaw Naval Special Warfare Command.

The defense secretary also introduced a new rule requiring all candidates for four-star general positions to meet personally with President Trump before their appointments could be finalized. According to Pentagon officials, this hurdle has slowed the promotion process, since it is often difficult to secure time in the president’s schedule for such meetings.

It was also revealed that Hegseth blocked Rear Adm. Michael Donnelly’s appointment as commander of the 7th Fleet after conservative media reported that, seven years earlier, the admiral had authorized a drag show aboard the aircraft carrier Ronald Reagan.

War on leaks

From the start of his tenure, Hegseth suspected his subordinates of leaking information to the press. In April, he fired three staff members he had personally brought into the Pentagon, accusing them of passing information to journalists.

Suspicions of leaks also led Hegseth to block the promotion of Lt. Gen. Douglas Sims. After an investigation cleared Sims of any wrongdoing, and following a request from the new chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Dan Kane, Hegseth did agree to the promotion — only to reverse the decision later. Ultimately, Sims chose to retire after 34 years of service.

Hegseth’s insistence on absolute loyalty to the president fostered distrust among the troops. Desperate to identify the sources of leaks, the Defense Secretary and his attorney, Tim Parlatore, began subjecting military personnel and Pentagon staff to lie detector tests. However, after numerous complaints, the White House ordered Hegseth to halt the practice.

The insistence on absolute loyalty to the president has fueled distrust among military personnel

Recently, the Pentagon also required journalists covering the department to sign a pledge not to disclose information unless it is approved for publication by the department’s leadership. Any articles citing classified or even internal Pentagon documents can now be grounds for revoking journalists’ accreditation.

Notably, Hegseth himself had previously been the source of leaks. He shared classified information on strikes against Houthi targets in Yemen in a private Signal chat, which by mistake had included journalist Jeffrey Goldberg of The Atlantic. He also reposted the same information in a chat that included his wife, brother, and attorney. On at least two occasions, Hegseth invited his wife to meetings with foreign military officials where confidential information was discussed.

The secretary’s brother, Phil, frequently accompanies him on overseas trips. Formally, Phil serves as a senior advisor to Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem and acts as a liaison with the Department of Defense. The 1967 federal anti-nepotism law prohibits government employees from hiring, promoting, or recommending relatives for any civil position they oversee. However, because Hegseth’s brother is formally not under his supervision and works in a different department, proving a violation of the law is difficult.

Naming the ship

President Trump decided to symbolically cement his control over the armed forces by renaming the Department of Defense as the Department of War. The new name partly revives the original title the department held at its founding in 1789. In 1947, it was renamed the Department of the Army and, together with the Department of the Navy and the newly created Air Force, was incorporated into the larger structure, which has been called the Department of Defense since 1949.

At the Oval Office ceremony marking the change, Trump lamented that the U.S. had not won a single major war under the Department of Defense, while the old name had bolstered military morale and struck fear into the hearts of enemies, helping the country prevail in two world wars. Speaking at the White House, Secretary of Defense Hegseth said, “We will strike, not just defend. Maximum lethality, not shaky legality.”

By law, only Congress can rename executive agencies, meaning the department will have two simultaneous titles — one de facto, and one de jure. The administration has already begun implementing symbolic changes: the Pentagon building received a new sign, and a plaque on Hegseth’s office door now reads “Secretary of War.” The department’s website, defense.gov, now automatically redirects to war.gov.

Hegseth did not wait for the official renaming and ordered the plaque on his office door replaced immediately

Such rebrandings are far from cheap. In 2022, the Biden administration decided to rename nine military bases that had been christened in honor of generals who fought for the Confederate side in the Civil War. At the time, Congress’s Naming Commission estimated the cost at over $21 million, while the Department of Defense itself put the figure at nearly $40 million.

Given that the Pentagon oversees more than 700,000 facilities and bases across all 50 states and in more than 40 foreign countries, replacing names, emblems, plaques, signs, and official stationery will cost significantly more than Biden’s relatively modest reforms. Sources within the department could not provide exact figures but estimated that the total could run into the billions.

The army in politics

The founding fathers of the United States, who secured the country’s independence from Great Britain, were deeply suspicious of the idea of a standing army. Fearing it could become the foundation of a future dictatorship, Congress regularly blocked attempts to create a large peacetime army, increasing military budgets only during times of war. In 1890, the U.S. Army was the smallest among those of the world’s major powers, numbering just 39,000 troops (for comparison, France had nearly 550,000).

As of 1890, the U.S. Army was the smallest among the major powers of the time

Unlike in Europe, American lawmakers long resisted the formation of a general staff to lead the army. For this reason, none of the various branches of the U.S. military ever became a powerful political force, and their operations have remained highly depoliticized — in sharp contrast to the situation in Central and South America.

In the United States, a distinct consensus developed between the military, the government, and society: the armed forces stay out of politics, the government does not use the military against its domestic opponents, and the public regards the military as a prestigious institution.

With Trump’s rise, that consensus appears increasingly uncertain. The examples of Milley and Kelly show that military leaders are growing more willing to speak out on political matters. On the other side, Trump himself sees the military as one of his most powerful tools of influence within the country. Meanwhile, public trust in the armed forces has sunk to its lowest levels in the past 20 years.