Domestic spending on vaccines and medications, subsidies for paying medical staff, and programs supporting mothers and newborns are being rapidly reduced in the United States, the United Kingdom, and continental Europe. At the same time, global health aid to low-income countries has fallen to its lowest level in 15 years, dropping by half since the end of the Covid pandemic. Funding for efforts to combat the three most widespread diseases — HIV, tuberculosis and malaria — are shrinking as well, leaving millions of the most vulnerable adults and children worldwide at risk. Bill Gates, the globe’s largest private donor, predicts that “2025 will be the first year since the start of the century when child mortality not only fails to decline, but actually rises.” If these trends are not reversed, a new wave of increasingly desperate migrants could soon be arriving in the same countries that have recently reduced their budgets for foreign aid.

Content

A record collapse

Who is cutting funding

What's no longer being funded and who may pay with their lives

What comes next

A record collapse

In 2025, external health assistance to the world’s poorest countries amounted to only $39 billion — the lowest figure in the past 15 years and less than half of the Covid-era peak of 2021, when it reached upwards of $80 billion. From 2024 to 2025 alone, the drop exceeded $10 billion, driven primarily by the shutdown of U.S. aid programs.

Experts offer grim projections: if current trends continue, funding will keep declining and could fall to $36 billion by 2030 — a level last seen in the late 2000s.

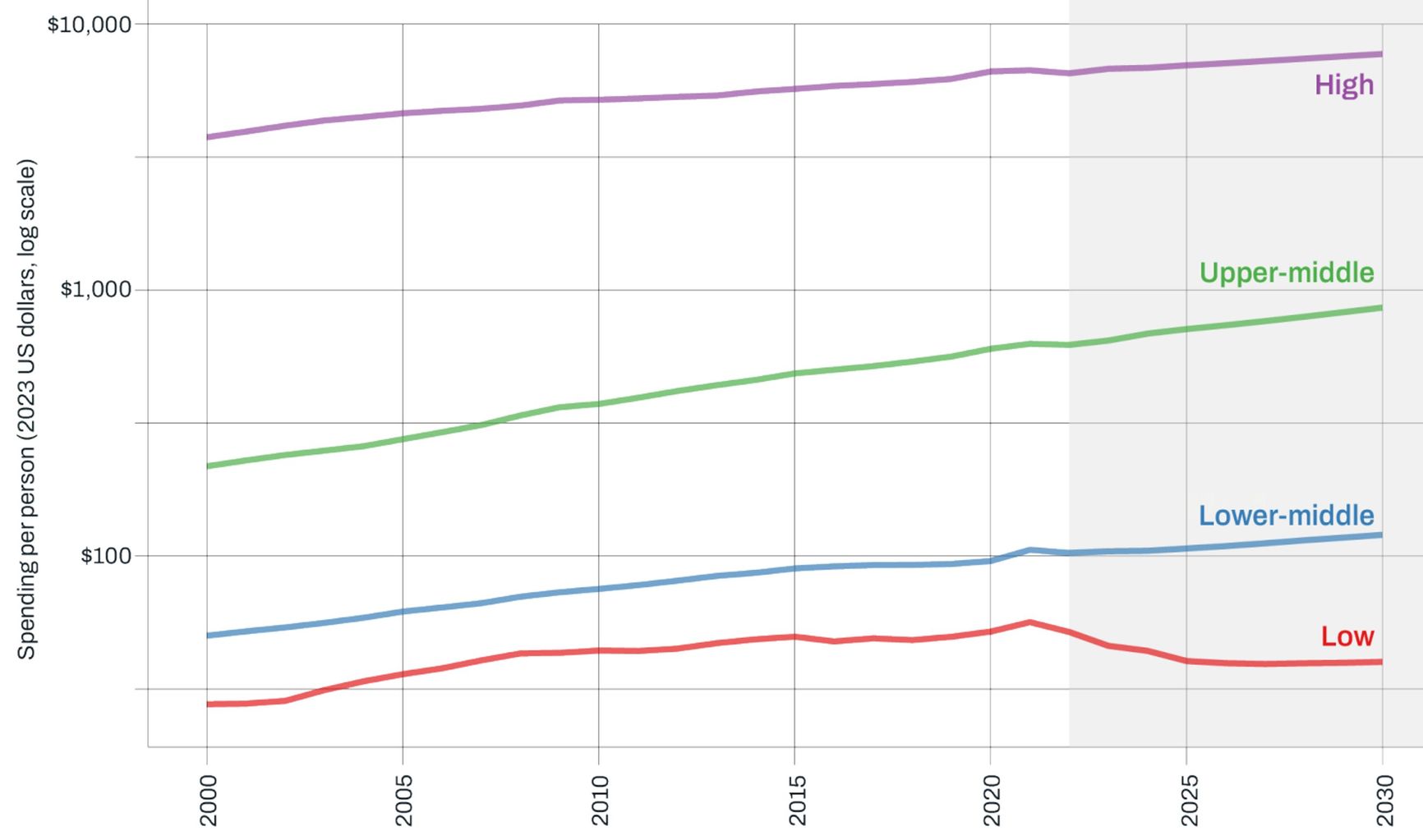

Per-capita healthcare spending by World Bank country groups, 2000–2030. Y-axis values are shown on a logarithmic scale (base 10) because of the sharp differences in spending levels between country groups. The color coding reflects groups by gross national income per capita: purple for high-income countries, green for upper-middle-income, blue for lower-middle-income, and red for low-income

The decline in funding threatens to erase progress in combating infectious diseases and reducing child mortality. Since the early 2000s, the annual number of deaths among children under five years old has dropped from 10 million to five million, but this curve may turn upward as early as the end of 2025, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation warns. In October, the world’s largest private donor laid out the stakes: “There’s never been a point in the past 25 years when more lives hung in the balance. In all likelihood, 2025 will be the first year since the turn of the century when the number of children dying will go up instead of down.”

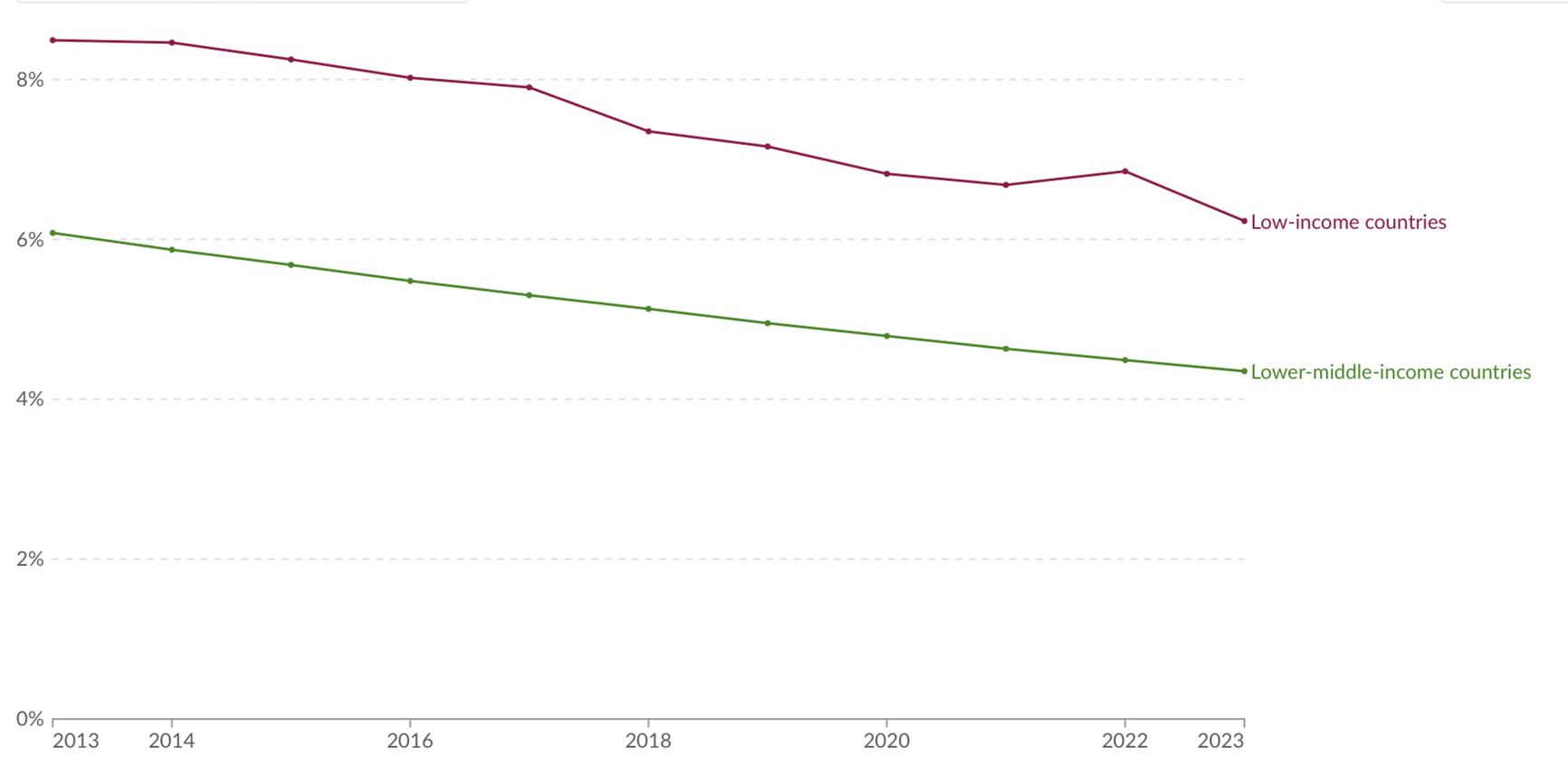

Child mortality curve for low- and lower-middle-income countries

In the communique that came out of the 2021 G7 summit in Cornwall, England, leaders pledged to prevent another pandemic. Now the same G7 is withdrawing support from the healthcare systems of poor countries.

Who is cutting funding

United States

For many years, the United States was the world’s largest health donor, providing more than 35% of global assistance. The PEPFAR program alone saved about 26 million lives over 21 years and prevented millions of new HIV cases.

But in 2025, U.S. policy on foreign assistance changed sharply: the government reduced funding by 67%, or $9 billion. The reason was Donald Trump’s return to the White House. Even PEPFAR, which was rolled out under the presidency of Republican George W. Bush, ended up partially frozen over concerns about “supporting activities related to abortion.”

At the same time, the White House announced the suspension of funding for the WHO and pledged to review its participation in the Global Alliance for Vaccines (GAVI). Researchers believe that if the United States continues on this path, by 2030 it will lead to more than 14 million additional deaths, including those of 4.5 million children under five.

United Kingdom

Although the United States has played the central role when it comes to cutting health funding for the developing world, it is far from alone. On Feb. 25, 2025, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced that London would reduce spending on development aid for poor countries — official development assistance (ODA) — by £6 billion in order to boost defense investment.

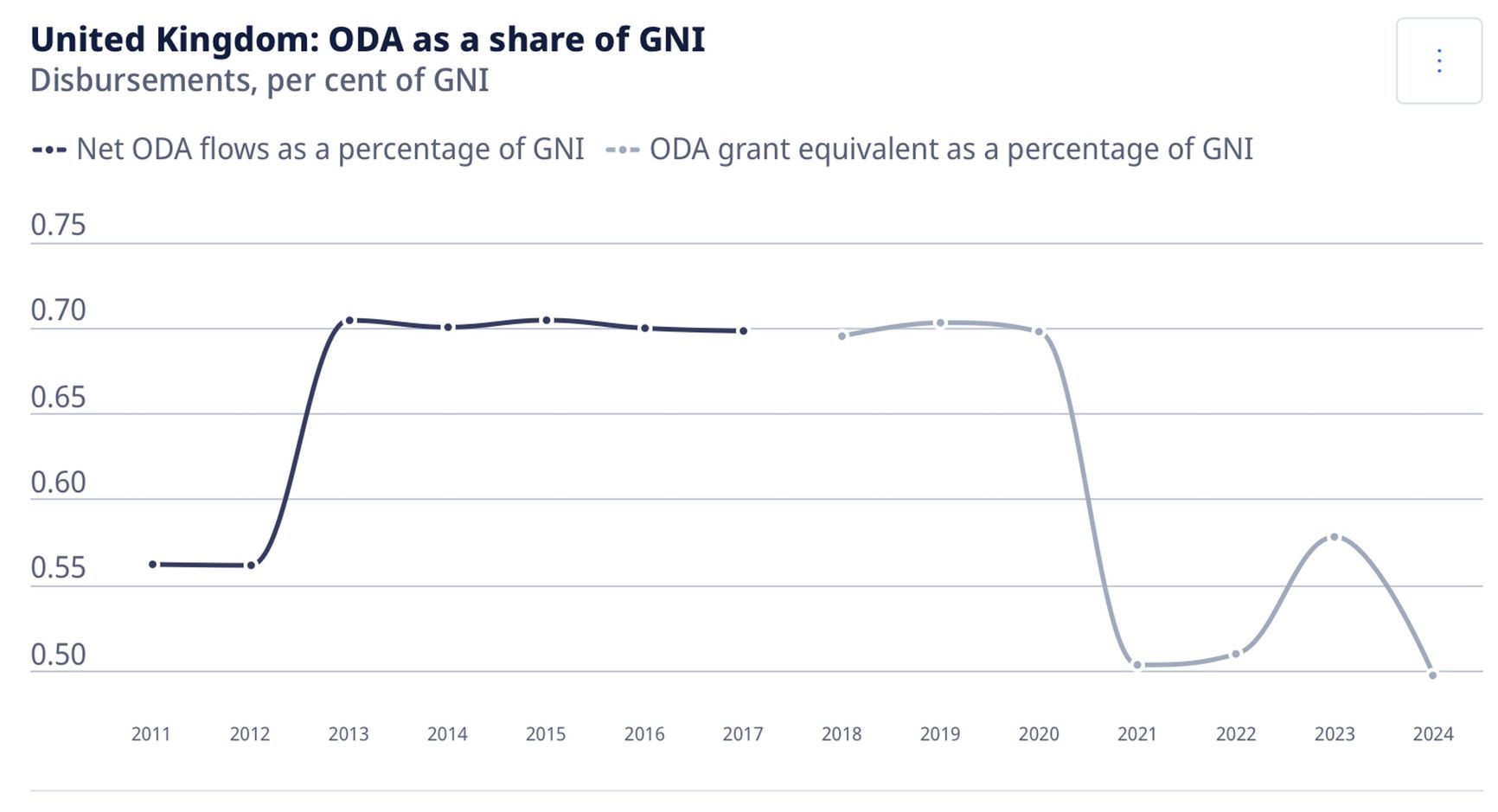

In 2020, the United Kingdom spent the UN-recommended 0.7% of its gross national income on ODA, but that share has now dropped to 0.5% and continues to fall. In absolute terms, preliminary data show that the UK reduced its development aid contributions in 2024 by £1.278 billion compared to 2023.

Share of the United Kingdom’s official development assistance (ODA) in gross national income (GNI), 2011–2024. Source: UK government

In the summer, the British government explained the reduction in foreign aid as being part of a move “towards a new relationship with developing countries, becoming partners and investors, rather than acting as a traditional aid donor.”

To the wider public, officials justify this redistribution by citing the need to address domestic problems, arguing that money saved on “donor” spending will be redirected to domestic needs. Ian Mitchell, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, summed Starmer’s decision by saying, “cutting funding for the world’s poorest people is the easiest — and cruellest — choice he could make”

According to a report put out over the summer, “the poorest countries will be hit hardest” by the UK’s spending cuts, with massive reductions in “funding to some of the countries hit hardest by humanitarian crises, including Ethiopia (25% reduction), South Sudan (23%), and Somalia (27%).

Continental Europe

Continental European countries are also pulling back. The largest donors to healthcare in low-income countries report plans to scale down their foreign aid. According to OECD forecasts, in 2025 its volume in European countries will fall by anywhere from 9% to 17%. In 2024 it had already dropped by 9%. If the OECD projections prove accurate, this will be the first time in history that the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany all reduce aid two years in a row.

How sharply will European countries cut their ODA budgets?

The Netherlands: the government announced a €350 million reduction in aid in 2025, with a projected decline to €2.5 billion per year by 2027.

Germany: the 2025 federal budget includes major cuts to agencies involved in official foreign assistance, with the total reduction coming in at €19.8 billion. The budget of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development will be reduced by €937 million, and that of the Foreign Ministry by €836 million.

France: the draft 2025 budget includes a €1.3 billion cut to ODA, roughly a 23% decrease compared to 2024.

European governments officially emphasize the need to focus on domestic challenges. Critics, however, argue that “ODA cuts have become an easy fix for budget gaps, despite being costlier than using ODA for conflict and crisis prevention in the long run.”

Private donations, unfortunately, cannot fill the widening funding gap. The Gates Foundation, for example, has allocated $1.6 billion for vaccinations in the poorest countries, but such a sum is nowhere near sufficient to make up the shortfall in aid from national governments.

What's no longer being funded and who may pay with their lives

Child vaccination

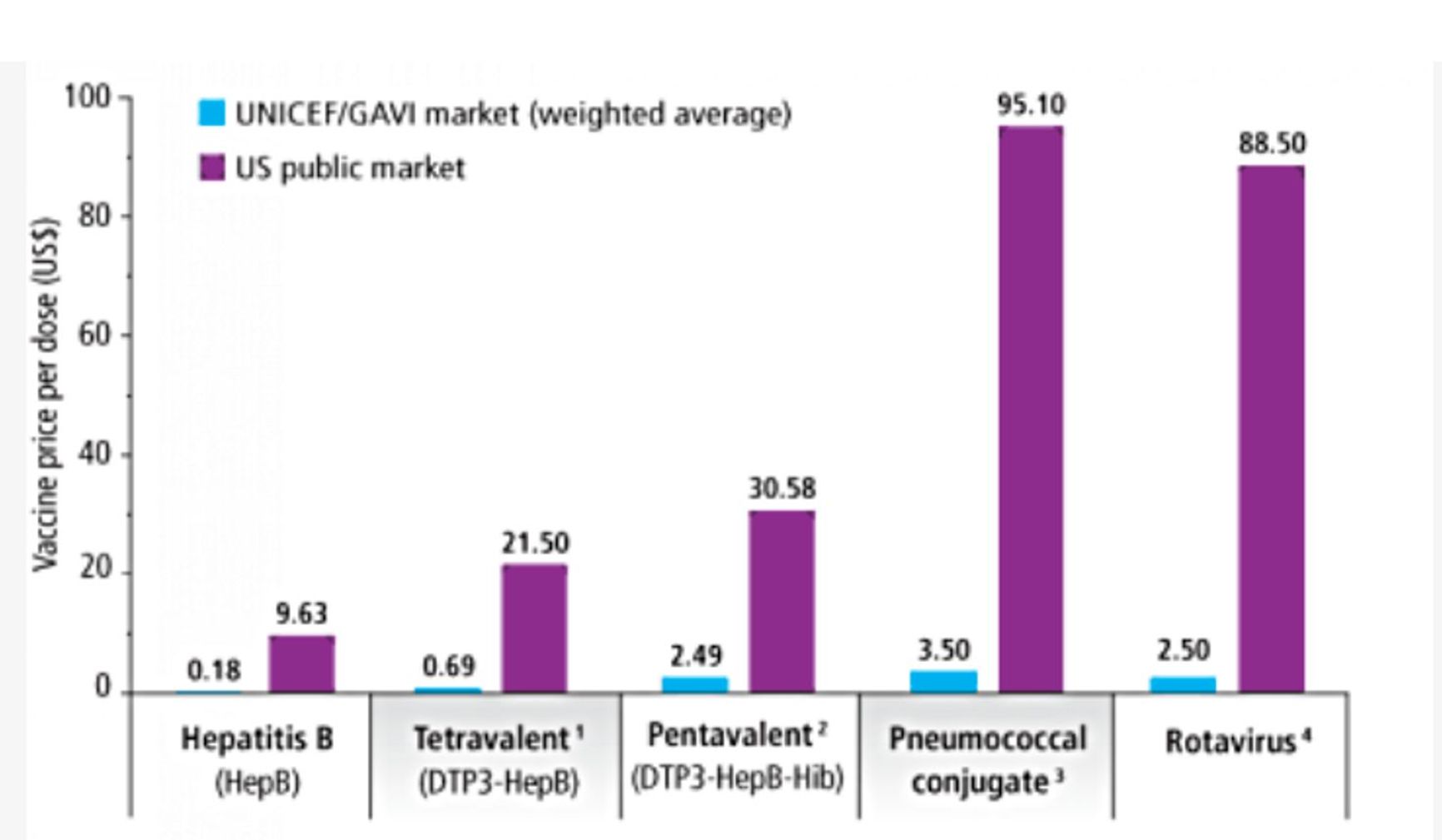

Over the past two decades, GAVI and UNICEF have completely reshaped the market for childhood vaccines. Previously, individual countries procured vaccines on their own. Now, however, a system of long-term aggregated contracts is in place, consolidating demand and driving prices down many times over.

The system works as follows: orders from several (or several dozen) countries are combined into one large contract, with volumes and delivery schedules fixed for three to five years. This allows manufacturers to reduce risks and thereby dramatically lower prices. Countries, in turn, receive uninterrupted supplies via the long-term agreements.

Price of a single vaccine dose on the UNICEF/GAVI markets (blue) and on the U.S. public market (purple). Thanks to long-term aggregated purchasing, the cost of key childhood vaccines for low-income countries is reduced by a factor of 10–30: for example, hepatitis B vaccine costs $0.18 through GAVI/UNICEF versus $9.63 on the U.S. market; the pneumococcal vaccine costs $3.50 versus $95.10 in the U.S.. Source: GAVI

With budget cuts at UNICEF and GAVI, contracts for vaccine production simply are not being signed, and the people suffering the most are children under five. Each year, UNICEF procures vaccines for 45% of all young children worldwide. In 2023 it delivered nearly 2.8 billion doses to 105 countries. But today, the situation is dramatically different. As the WHO warned in July 2025:

“Nearly 20 million infants missed at least one dose of DTP-containing vaccine last year, including 14.3 million ‘zero-dose’ children who never received a single dose of any vaccine. That’s 4 million more than the 2024 target needed to stay on track with Immunization Agenda 2030 goals, and 1.4 million more than in 2019, the baseline year for measuring progress.”

GAVI estimates that around 1.2 million potential child deaths will occur over the next five years if U.S. support for vaccine procurement ceases.

HIV, tuberculosis, malaria

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria is an international pooled financing mechanism established in 2002. It raises money from donor governments, private foundations, and the corporate sector, directing those resources into treatment, diagnostics, and prevention of the three deadliest infectious diseases — HIV, tuberculosis and malaria. The Global Fund primarily operates in low- and middle-income countries. According to the organization, more than 70 million lives have been saved since 2002.

The fund has now confirmed a cut of $1.43 billion in the current financing cycle. This is roughly 11% of the amount originally pledged for the 2024–2026 period. Representatives say the fund will continue to support essential programs, but NGOs fear a repeat of the 2025 crisis, when the U.S. administration froze USAID, triggering a collapse of medical and humanitarian programs worldwide.

Neonatal and maternal care

The most effective interventions for saving the lives of mothers and newborns include the provision of prenatal care, treatment of postpartum hemorrhage, maternal nutrition, antibiotics for newborns, and rehydration therapy for diarrhea. Individually, these interventions are inexpensive, and they save a vast number of lives. Every dollar invested yields an 83-fold return when measured in years free from severe illness or disability.

But this type of care is among the first to face cuts, according to a WHO report, “humanitarian funding cuts are having severe impacts on essential health care in many parts of the world, forcing countries to roll back vital services for maternal, newborn and child health.”

WHO analysts warn of grim consequences: low-income countries will lose access to vaccines, emergency obstetric care, and basic neonatal services, followed by disease outbreaks and rising infant and maternal mortality.

Why budget cuts are so dangerous

Reducing health spending in low-income countries would inevitably hurt vulnerable groups at any time, but what is happening now carries critically dangerous consequences. Three factors are to blame: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the increasingly visible effects of climate change, and large-scale population displacement.

During the 2020–2022 pandemic, poorer countries took out loans to provide their citizens with essential supplies such as tests, ventilators, and oxygen. They must now repay those debts, which is squeezing their own budgets, including outlays on healthcare.

Climate change is another major factor. According to WHO forecasts, between 2030 and 2050 it will cause about 250,000 additional deaths each year due to increases in hunger, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress alone. The direct cost to health systems by 2030 is estimated at $2-4 billion a year. “Areas with weak health infrastructure — mostly in developing countries — will be the least able to cope without assistance to prepare and respond.” the organization warns.

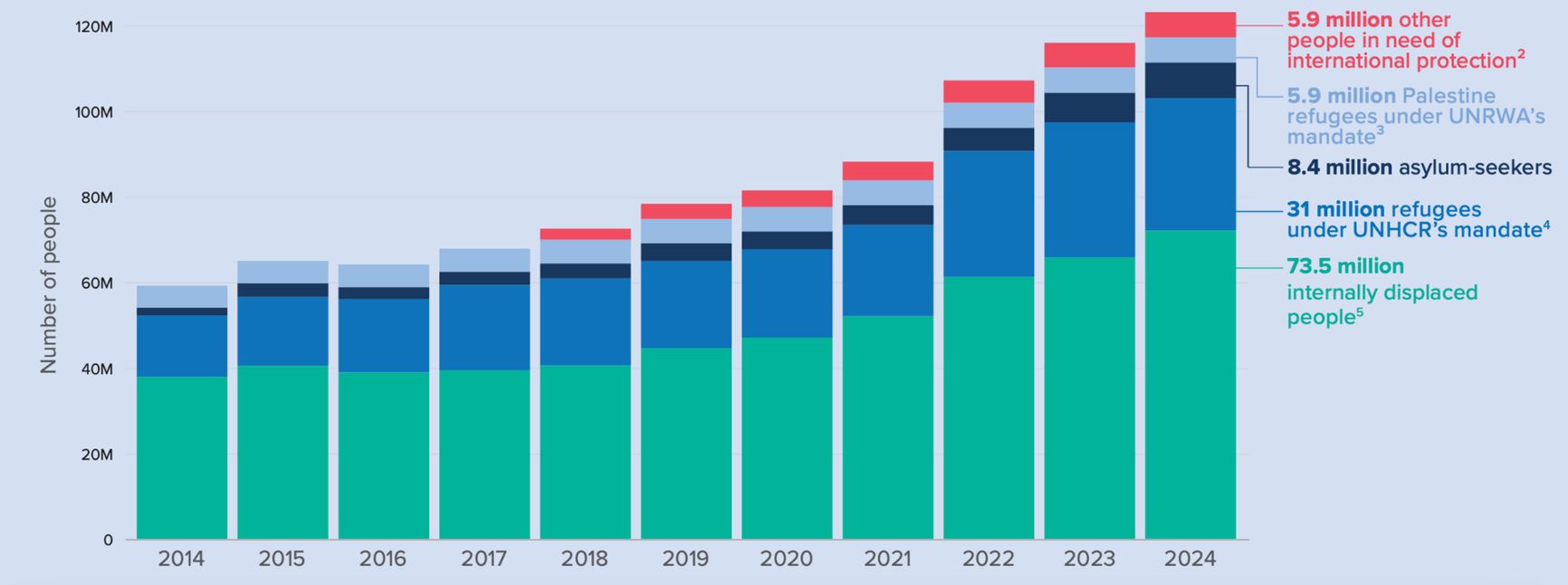

According to UNHCR, by the end of 2024 about 123.2 million people had been forced from their homes due to persecution, conflict, violence, or human rights abuses.

The total number of people forced to flee their homes has been rising for ten consecutive years, and it reached a record 123.2 million in 2024. This figure included 73.5 million internally displaced, 31 million refugees under the UNHCR mandate, 8.4 million asylum seekers, 5.9 million Palestinian refugees, and another 5.9 million people in other groups requiring international protection. Chart: UNHCR data

Crowds of people in camps and transit zones are triggering outbreaks of infectious diseases, including cholera, at a time when preventive resources are already in short supply.

What comes next

Now, less than two years since most of the budget cuts went into effect, the world is already seeing the return of local epidemics. African countries are suffering the most, as hot climates accelerate the spread of infections such as malaria. Deaths from the disease in Cameroon fell from 1,519 in 2020 to 653 in 2024, but the number is rising again, Reuters reports.

Maternal mortality is also expected to keep worsening. The UN warns that budget cuts could wipe out all progress made in this area, even though global maternal deaths fell by 40% between 2000 and 2023.

Over the next three to five years, disruptions in vaccination will leave entire groups of children and teenagers at heightened risk of disease. Incomplete treatment courses for tuberculosis and malaria, driven by a lack of funding, will lead to growing drug resistance and higher mortality. The consequences will extend beyond epidemiology — trust in official medicine among poor communities will come under threat, fueling further increases in illness and death.

Researchers project that if U.S. funding ceases entirely between 2025 and 2030 (without replacement from other sources), the following worldwide impacts would be expected:

• 1.6–6.6 million extra deaths from HIV/AIDS;

• 466,000–768,800 additional deaths from tuberculosis;

• 1.3–4.5 million additional child deaths from other causes;

• 40–55 million unintended pregnancies and 12–16 million unsafe abortions.

Declining vaccination coverage and increasing antibiotic resistance will lead to significant economic downturns. According to World Bank estimates, drug-resistant infections could erase decades of progress, as malaria alone has historically reduced GDP growth by 1.3% per year in endemic regions.

But the resulting problems will not be confined to the developing world. Poverty and climate change are driving migration, meaning even more desperate people will soon be seeking refuge in the same countries that are cutting back on the provision of medical aid today.