After the recent death of former Uruguayan president José “Pepe” Mujica, obituaries around the world called him “the world’s poorest president.” Mujica really did live in a modest house in the countryside and drove an old Volkswagen Beetle. And yet, under the steady guidance of left-leaning governments, Uruguay has seen impressive GDP growth, achieved historically low unemployment numbers, and reduced poverty levels. The country has surpassed the United States to join the ranks of the world’s 15 most democratic nations, and it now boasts the lowest corruption perception rate in Latin America.

Mujica’s political journey mirrors the transformation of Latin America’s left in the 20th century — from dreams of overthrowing capitalism via armed struggle to a more pragmatic, social-democratic approach after the lessons of the Cuban revolution were learned. He not only became Uruguay’s most popular modern leader, but also a moral reference point for Latin America as a whole — and for many beyond its borders.

Content

Children of the revolutions

The end of the dictatorship

The people’s president

Uruguay, a small South American country with a population of around 3.5 million, is often confused abroad with Paraguay. But on May 13, news of Mujica’s death made headlines across the globe under the same striking phrase: “The world’s poorest president has died.” How did the leader of a country once nicknamed “the Switzerland of Latin America” come to be known as both its humblest and its most iconic figure of modern times? Where does the myth end and the reality begin?

Children of the revolutions

Pepe, as Uruguayans called José Mujica, was once among the most active members of the leftist radical movement known as the Tupamaros, founded in 1963 at a moment when Uruguay was sliding toward political and economic crisis. Young revolutionaries saw in the turmoil an opportunity to seize power by force and build a brighter future.

José Mujica is not the only 21st-century Latin American president with a revolutionary past. One need only recall former Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff or Colombia’s current president Gustavo Petro, both of whom took part in guerrilla movements in their youth. Or former Chilean president and Socialist Michelle Bachelet, who joined the resistance against the dictatorship after the military coup of 1973. All of them eventually moved away from dreams of reshaping the world through violence and turned instead to fighting for their ideals through democratic means. The victory of the Cuban Revolution in 1959 had inspired many on the Latin American left to try to replicate its success, and guerrilla movements sprang up in several countries before that particular model of effecting social change was discredited.

In Uruguay in the 1960s, the urban guerrilla campaign grew so large that the government banned the press from reporting on the Tupamaros — or even so much as mentioning their name. Some journalists began referring to them as “the unmentionables,” and readers knew exactly who they meant.

In 1968, the president of Uruguay declared a state of emergency, suspended all constitutional protections, and jailed several of his political opponents. In 1969, a public opinion poll showed that 40 percent of Uruguayans believed the Tupamaros were noble revolutionaries acting out of idealism (and sympathy for them lingers in Uruguay to this day). The crackdown only fueled the Tupamaros’ armed campaign against the regime, triggering a new wave of violence and repression. In 1973, just three months before Chile’s military coup, Uruguay became an open military dictatorship.

One episode from this period — the kidnapping and subsequent murder by guerrillas of U.S. adviser Dan Mitrione, who was training Uruguayan police and military in the effective use of torture — became the basis for the 1972 French-Italian political thriller State of Siege, directed by Greek-French filmmaker Costa-Gavras and starring Yves Montand. The film went on to win several international awards.

By the early 1970s, the Tupamaros had been crushed. Most of their leaders were imprisoned, while a few managed to flee abroad. José Mujica spent 14 years behind bars (1972–1985), enduring some of the harshest conditions imaginable: solitary confinement, isolation cells, torture, no visits, no books, no time outdoors. He later recalled speaking with mice and insects just to keep from losing his mind.

Many years later, in 2018, during the filming of Emir Kusturica’s El Pepe, a Supreme Life, Mujica said: “Without those years of solitude, I would have been more useless, more frivolous, more superficial. I would have basked in success.” That refusal to bask in success is what sets Mujica apart from other Latin American leftist leaders who also abandoned violence but went on to become conventional moderate politicians — many of these were later accused of corruption.

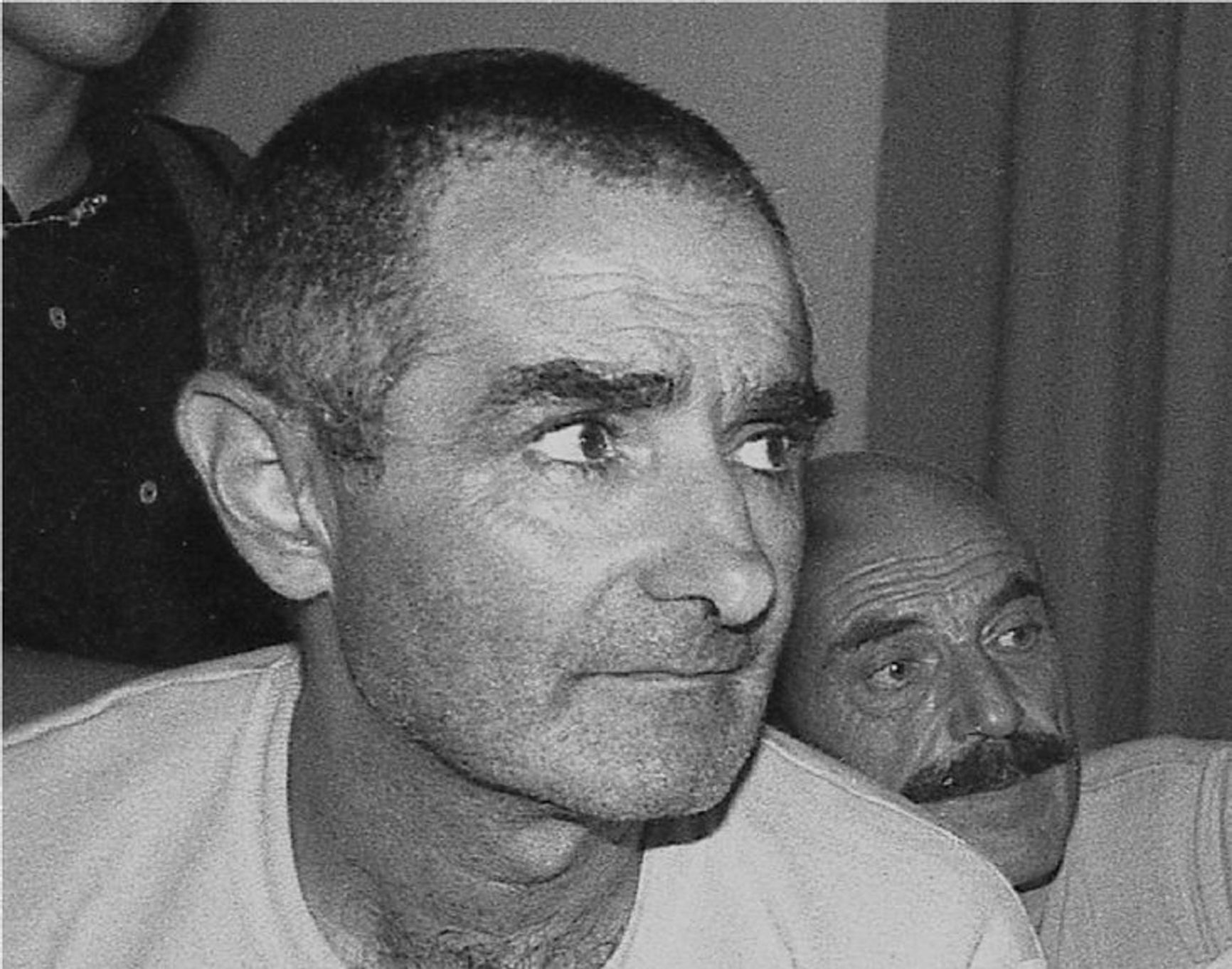

José Mujica after his release

Similarly repressive processes were underway in neighboring countries. From the 1960s through the 1980s, military dictatorships dominated in Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay. All of them attempted, to varying degrees, to implement neoliberal economic policies, but only in Chile did these policies yield any notable macroeconomic success — which, however, had little effect on living standards for most of the population and ultimately led to Pinochet’s departure after he lost a nationwide referendum in 1988.

In Uruguay, the dictatorship’s demise came more quickly. In 1980, Chileans voted in favor of a new constitution proposed by Pinochet to legitimize his rule, while Uruguayans voted against the continuation of their own military junta. It was the first time a dictatorship had been defeated in a plebiscite that the regime itself had called.

Uruguayans voted against the military junta: it was the first time a dictatorship had been defeated in a plebiscite it had called for itself

In Uruguay, the military was forced into dialogue with political parties. Civil rights and individual liberties began to be gradually restored, along with the return of political parties, trade unions, and the free press. After several general strikes paralyzed the country amid a deepening economic crisis, the military opted to hand over power to a civilian government.

The end of the dictatorship

In late 1984, Uruguay held presidential elections. In addition to the two traditional right-wing parties — the Blancos and the Colorados, which had alternated in power since 1836 — a new player entered the race: the Broad Front, a center-left coalition. Julio María Sanguinetti of the Colorado Party took office in 1985 and declared a blanket amnesty, covering both the victims of the dictatorship and the perpetrators in the military. Among those released from prison was José Mujica.

One of the most divisive debates in parliament and society concerned the “Expiry Law,” which effectively granted the military immunity from prosecution for serious human rights violations during the dictatorship. Uruguayans came to call it the “impunity law.”

The Broad Front, the Catholic Union, trade unions, and other organizations collected more than 555,000 signatures — a number representing 25% of registered voters — to force a referendum on the law. In the lead-up to the vote, the military and right-wing parties waged a vigorous propaganda campaign, arguing that the full amnesty declared by President Sanguinetti had given the country four years of stability and subordination of the military to civilian authority. Putting officers on trial, they warned, could provoke unrest and a new coup.

In the 1989 referendum, 85% of eligible voters took part. Of them, 57% voted to uphold the Expiry Law. Most of the law’s supporters were middle-aged or older. Among young people aged 18 to 29, 75% voted to repeal the “impunity law.”

Uruguayans continued to demand investigations into disappearances that had occurred during the dictatorship. Around 200 people were officially listed as missing, and according to Amnesty International, 100 Uruguayans were abducted and disappeared in Argentina. The region’s military dictatorships had coordinated their actions.

Roughly 60,000 people — about 2% of Uruguay’s population — were imprisoned during the dictatorship, a global per capita record at the time. Emigration was also massive: one in every ten Uruguayans left the country.

During the dictatorship, one in every ten Uruguayans left the country

In 2005, Tabaré Vázquez, leader of the Broad Front and the newly elected president of Uruguay, ruled that certain crimes were not covered by the Expiry Law. This led to a number of trials, and two of the five former presidents of the civic-military dictatorship period, Juan María Bordaberry and Gregorio Conrado Álvarez, were handed prison sentences. Every May since 1996, Uruguay has held an annual Silent March that draws thousands of participants, who carry photographs of the disappeared and demand truth and justice from the state.

The silent march

Such issues have always divided society, and José Mujica's stance was controversial even among many of his fellow former prisoners — he opposed prosecuting the military. In one of his final interviews, with the Spanish newspaper El País, he reflected:

“I didn’t turn the page. I simply chose not to spend time settling scores — and that’s something very different. You can’t live in the past; there are things that can’t be changed. They are what they are. In life, there are wounds for which there is no cure, and we must learn to live on. I know some people won’t agree with me, but I chose a more rational and less sentimental position. That’s why I didn’t use power to go after the military. There are people who may have wanted more, but we’re not going to change the past. I’m concerned about what comes next. We must try to ensure that yesterday doesn’t hold us back from moving toward the future.”

The restoration of democracy in Uruguay and the release of political prisoners sparked intense debate within the old Tupamaros. Most of them — including José Mujica — chose to pursue legal political struggle. They founded the Movement of Popular Participation, which later joined the center-left Broad Front coalition and began contesting elections.

In 1994, Mujica was elected to parliament as a Broad Front deputy. Five years later, he became a senator, emerging as one of Uruguay’s most popular politicians. He was already well known for his modest lifestyle: after his release from prison, Mujica bought a small farm outside the city to grow flowers, and in 1986 he and his wife moved into a modest single-story home on the property. Mujica rode a motor scooter to his first parliamentary session and never left his little house. When he became president, he remained in the home while adopting a Volkswagen Beetle as his preferred mode of transport.

The president and his 1987 Volkswagen Beetle

Tabaré Vázquez, who served as president from 2005-2010 (and again from 2015-2020), effectively broke Uruguay’s traditional two-party system for the first time in the country’s history, pushing the right-wing parties out of power. He began implementing the Broad Front’s center-left program, which included tax reform, the strengthening of social protections, and the expansion of healthcare. Vázquez also succeeded in carrying out pension reforms and repaid an IMF loan ahead of schedule, all of which contributed to GDP growth and a decline in poverty. By the end of his term, Vázquez had the highest approval rating in the country’s history — 71%.

In 2005, Mujica was appointed minister of livestock, agriculture, and fisheries. Even though he was not an expert in this sector, which is critical to Uruguay’s economy, his political experience, exceptional ability to engage with the public, and instinctive grasp of public opinion were valuable assets that allowed him to succeed in the job. Mujica’s performance boosted his popularity, and in the next election he became the Broad Front’s presidential candidate.

On November 29, 2009, tens of thousands of Uruguayans took to the streets to celebrate José Mujica’s victory. Addressing the crowd, he thanked the outgoing president, saying it was the broad public approval of Vázquez’s work that had made another Broad Front victory possible. Mujica also addressed his opponents and thanked the defeated right-wing candidate for his timely concession and calls for national unity.

Tens of thousands of Uruguayans celebrate the election of José Mujica in 2009

The rise to power of a president like Mujica was no accident: it was made possible by Uruguay’s long-standing democratic traditions, its strong political institutions, and its well-educated population. The country’s two-party system took shape back in the 19th century, and its first constitution was adopted in 1830, five years after the declaration of independence from Brazil. Many of the constitution’s provisions remain in force today, even after multiple reforms, and compulsory primary education has been a public good since 1877.

Soviet diplomats who worked in Uruguay during the 1950s and 1960s — when the country already had the highest per capita GDP on the continent — had a saying: “If there’s a paradise on Earth, it must be Uruguay,” a loose interpretation of the popular Uruguayan phrase Como el Uruguay no hay (“There’s no place like Uruguay”). That was a period of economic prosperity driven by monoculture exports of livestock products. But it came to an end with a collapse in global prices for meat and wool, triggering an economic crisis and eventually a military dictatorship — a rupture in the country’s democratic tradition that failed to bring prosperity. After that, Uruguay began a gradual shift to the left.

The people’s president

Today, Uruguay is seen as a country of socially oriented capitalism that, thanks in large part to its center-left governments, has avoided many extremes. In his inaugural address, Mujica stressed the importance of shaping policy that goes beyond a single presidential term and that is relatively independent of the ruling political party. He outlined four main priorities: education, security, the environment, and energy, and he invited the opposition parties in parliament to form working committees on these issues.

Mujica had a gift for building consensus and finding compromise through a focus on shared interests. In Uruguay, rather than highlighting Mujica’s individual role, people are more inclined to emphasize the continuity of his policies with those of his predecessor — who, incidentally, returned to the presidency after Mujica left office (Uruguayan law prohibits serving two consecutive terms). Uruguayans appreciated Mujica for his unique personal qualities, his simplicity, and the philosophical depth of his thinking. There is no personality cult around Mujica — only a shared understanding that the country’s achievements were the result of collective effort that continued under his watch.

There is no personality cult around Mujica — only the understanding that success came through collective effort

During Mujica’s presidency (2010–2015), Uruguay’s economy grew steadily, and the country managed to avoid the worst effects of the 2008 global financial crisis. According to World Bank data, per capita GDP rose from $12,600 to $17,100, and the country’s total GDP increased from $40.3 billion to $57.1 billion. Inflation held steady at 7–9%.

Uruguay’s foreign economic policy was guided by pragmatic cooperation with a range of partners. One notable achievement involved gaining access to the Asian market for Uruguayan beef — the backbone of the country’s agricultural exports. (Uruguay is one of the world’s leading beef exporters and ranks among the top countries in meat consumption, which has reached 100 kg per person per year.)

Uruguay also achieved success in environmental policy: by 2015, nearly 95% of the country’s electricity was generated from renewable sources. This, too, represented continuation of past reforms — since 2008, Uruguay had been investing 3% of its GDP annually into transforming its energy sector through public-private partnerships.

Addressing social issues was a top priority for Mujica. Between 2010 and 2015, poverty was cut from 18.5% to 9.8% — down from 32.6% in 2006. Unemployment dropped to the lowest levels in the country’s history, ranging between 6.3% and 7.5%. Mujica launched the “Together” social housing plan, funded by donations from private companies. The program provided housing for 15,000 families, and Mujica personally contributed up to 85% of his salary toward its implementation. The country’s Gini index hovered around 40 points — relatively high for a developed democracy but quite good relative to other Latin American countries.

In 2012, Uruguay passed a law legalizing abortion — a highly divisive issue in Catholic countries — becoming the second Latin America state, after Cuba, to legalize the procedure. In 2013, a law legalizing same-sex marriage came into effect, granting same-sex couples all the rights available to other couples. Uruguay was the second country on the continent to implement such a reform (after Argentina in 2010) and just the twelfth in the world.

Uruguay was also the first country in the world to legalize marijuana. In 2013, a law was passed fully decriminalizing the cultivation, sale, purchase, and use of cannabis. Mujica’s policy achieved his main goal: once marijuana became widely accessible, the popularity of heroin and cocaine dropped sharply, and Uruguay ceased to be a profitable hub for drug trafficking. In 2014, Mujica was even nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for signing the law.

In 2013, Uruguay became the first country in the world to legalize marijuana.

Although Mujica preached strict austerity, his government significantly increased public spending, which led to a rise in the budget deficit and prompted his opponents to accuse him of wastefulness. Nevertheless, by the end of his presidency, his approval rating stood at right around 70%, and his predecessor Vázquez succeeded him after winning 56.5% of the vote.

In 2015, at the age of 80, José Mujica left the presidency and was later elected to the Senate. Importantly, the country continued to develop after his departure. In the 2024 Global Democracy Index, compiled annually by The Economist, Uruguay’s average score of 8.67 marked it not only as the most democratic country in Latin America, but placed it 15th in the world — higher on the list than the United States and roughly on par with Canada. According to Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index, Uruguay also has the lowest level of perceived corruption in Latin America, ranking 13th globally, between Estonia and Canada.

Mujica’s formal career ended with his early resignation from the senate in 2018 — characteristically, he declined to receive a senator’s pension — but he remained actively involved in the country’s political life to the extent that his health allowed. In May 2024, Mujica was diagnosed with cancer but still made several appearances during the election campaign in support of Broad Front candidate Yamandú Orsi, who won the election last November and was sworn in as president on March 1. In January 2025, Mujica announced that the illness was untreatable and bid farewell to his fellow citizens, acknowledging that his time had come and refusing to give further interviews. He died on May 13, one week short of his 90th birthday.

Funeral of José Mujica, 2025

In his final interview, Mujica said:

“There is nothing better than democracy. When I was young, I didn’t think so — that’s true. I made a mistake. But today, I fight for it. It’s not a perfect society, but it’s the best possible... It’s easy to respect those who think like you do, but you must understand that the foundation of democracy is respect for those who think differently.”

Mujica was aware that his personal philosophy was not for everyone, and this understanding helped him accept other people as they were. As he quipped in a 2013 interview: “If I asked people to live as I live, they would kill me.”