In April, in an effort to counter acts of sabotage against the country’s railways, it emerged that Russia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs was establishing special police units outfitted with armored vehicles. Since the outset of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, explosions on tracks, incidents of arson targeting railway infrastructure, and other acts of sabotage have become commonplace across Russia. By September 2023 — 19 months into the war — the human rights group Solidarity Zone had used open source data to count 111 such incidents. One of the most serious occurred in November 2023, when an explosion in Russia’s central Ryazan Region derailed 19 wagons. At the time, investigators had the names of no concrete suspects — only a bicycle tire track, a vague silhouette caught on camera, and a composite sketch pieced together from fragmentary descriptions. Three weeks later, a police officer detained a man in the courtyard of an ordinary apartment block — an encounter that would mark the beginning of a high-profile terrorism case against anarchist Ruslan Sidiki. If convicted on multiple charges, Sidiki could face a life sentence. Drawing from the case materials, The Insider has reconstructed the story of the manhunt, tracing it from a blurry surveillance image to a chance encounter at an apartment entrance.

Content

Explosion at dawn and a camera in a sock

A blurry silhouette: The first leads

Searching for the guerrilla: “No operationally significant information obtained”

The Wagner trace

A retired KGB saboteur weighs in: A careful plan and a clean assembly

“He's definitely not local”: The guerrilla gets a face

A chance encounter: “I made a couple of mistakes”

Investigative methods: “I was this close to f***ing up every cyclist in Ryazan”

Final reflections: “I don’t regret what I did”

Explosion at dawn and a camera in a sock

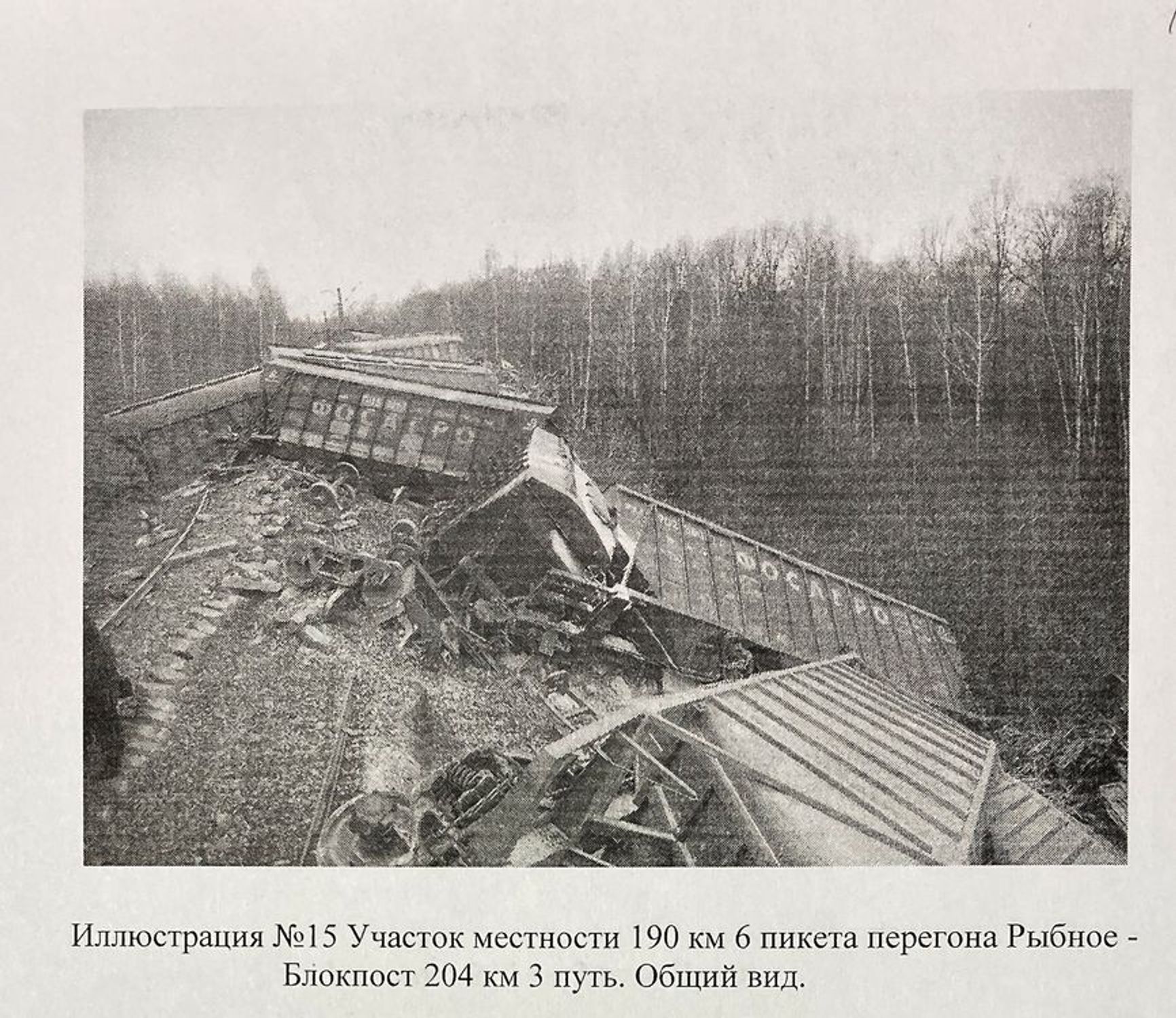

At 7:10 on the morning of Nov. 11, 2023, nineteen freight cars of train No. 2018 derailed on a stretch of track running between the “Rybnoe” and “Block Post 204 km” stations, not far from the city of Ryazan. The train, weighing 5,154 tons, was carrying apatite concentrate from the far northern Murmansk Region to the Saratov Region, which borders Kazakhstan. Driver Dmitry Unshakov and his assistant, Sergey Tarabukin, were in the engine cab.

“We were moving at a speed of 54 kilometers per hour,” Unshakov would later recount during interrogation. “There was a loud bang. The side windows in the locomotive cab, where my assistant and I were located, were blown out, and the front windows cracked. I saw the wires above the tracks swinging wildly, so I immediately applied emergency braking.”

While Tarabukin went to inspect the train, Unshakov reported the incident to the dispatcher. Upon returning, Tarabukin confirmed the situation: the wagons had derailed. He later testified that there had been only one explosion. The brake system pressure remained stable, and he had not seen any strangers on the tracks.

At the scene there were twisted railroad ties, and a section of rail was cut clean through — an uneven break consistent with the results of an explosion. A crater approximately 4.5 by 3 meters was found. Metal rods protruded from the gravel. Splinters of ties, debris, and torn-out fastenings were scattered about. The overhead contact line was damaged, with one of the supporting poles missing. Forest stretched along both sides of the tracks.

«Як би нам не було важко, нам більше не буде соромно»

Security forces arrived almost immediately: agents from the FSB, the police, the Investigative Committee , the Center for Combating Extremism, the Russian National Guard (Rosgvardia, a militarized internal security force directly subordinate to Vladimir Putin), canine units, and a traffic police crew — more than 25 people in total. Later, an OMON sapper-engineer from the “Vyatich” squad arrived. After inspecting the blast site, he concluded that over 10 kilograms of explosives, measured in TNT equivalent, had been used.

The sapper also found circuit boards wrapped in electrical tape, batteries, the casing of a syringe filled with powder, traces of white residue, and a black sock containing a video camera attached to a tree approximately five meters above the ground.

“I saw that a camera lens was sticking out of the sock. It was a video camera, but it showed signs of being booby-trapped. To neutralize the device, we decided to saw off the part of the tree where it was hanging, but we didn’t have time — the camera exploded and caught fire. It was a self-destructing device, likely triggered by a target sensor,” the sapper later testified.

Service dogs were brought in to sweep the area. One started from the site of the derailment, walking along the railway track past the tree with the camera and then into the forest. There the dog reached a gravel road and turned onto a dirt path before the trail ended.

Another canine team searched the surroundings, including relay cabinets and signal blocks — but found no traces of explosives or other telltale odors.

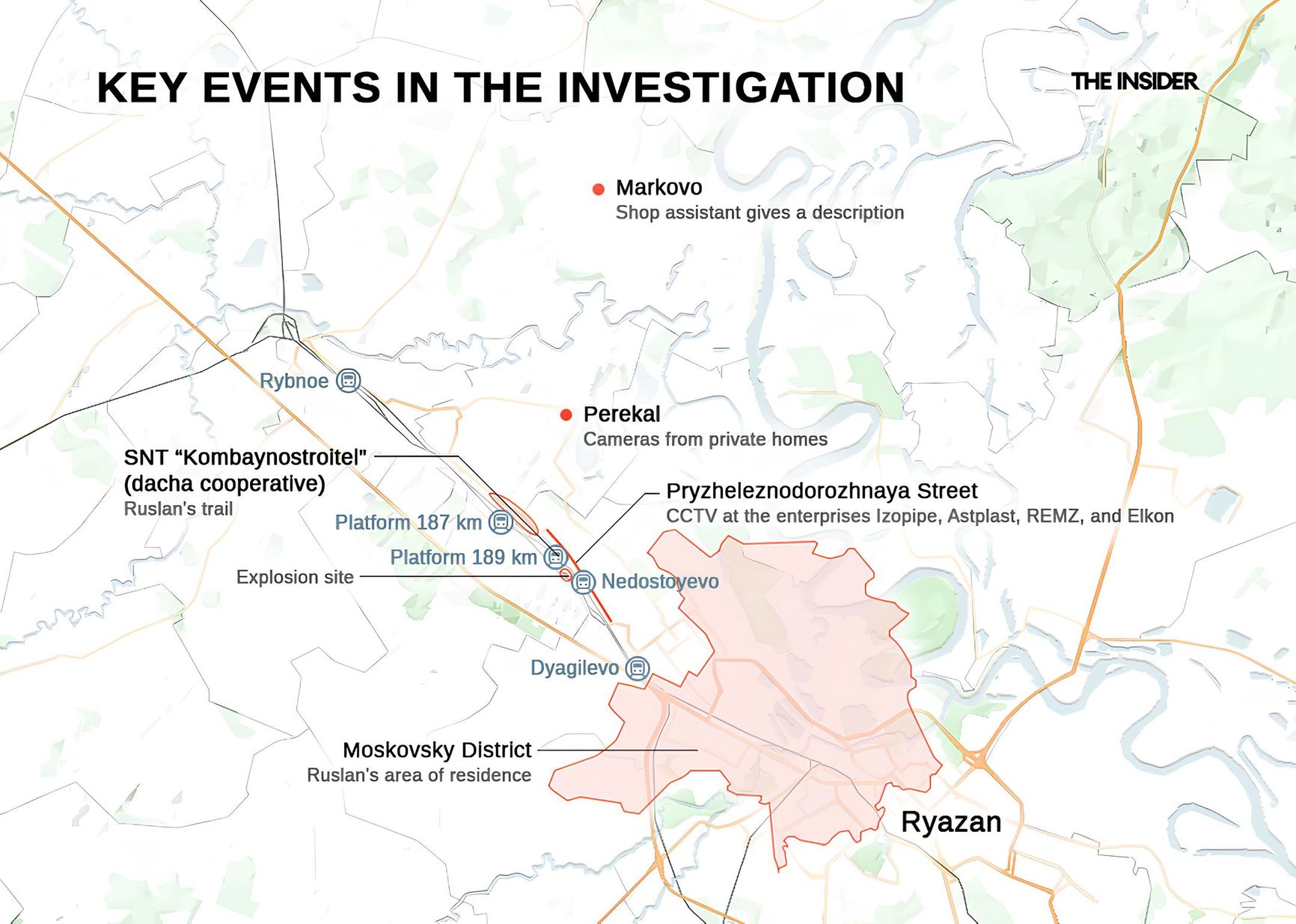

At the same time, investigators canvassed the surrounding area. On a road leading toward Rybnoe, they discovered bicycle tire tracks leading toward a dacha (summer house) cooperative called “Kombaynostroitel” (meaning “Combine Harvester Builder”). On the shoulder of Prizheleznodorozhnaya Street in Ryazan, they found another clear tread mark veering toward the forest belt. Opposite one of the buildings on this street was a footpath leading toward the tracks. Along this trail, investigators later found a spot showing clear signs of a “hideout” — flattened leaves covering an area about one by two meters.

This was the first time the theory of a cyclist emerged.

«Як би нам не було важко, нам більше не буде соромно»

The official damage caused by the explosion was assessed at over 800,000 rubles (almost $10,000) to the cargo shipper and more than 30 million rubles ($363,000) to Russian Railways — the country’s government-owned operator. The authorities classified the incident as a terrorist attack. According to investigators, a homemade explosive device had been used.

The search for those responsible began.

A blurry silhouette: The first leads

The next day, Nov. 12, investigators began questioning anyone who might have seen anything suspicious. Among the first to be interviewed was a traffic police patrol crew that had been in the area of Promyshlennaya Street the night before. One officer recalled that between 2:30 and 3:00 a.m., a man riding a bicycle had traveled in the same direction as their patrol car. He could not recall the cyclist’s face, the make of the bicycle, or what the rider was wearing — but it was the first lead.

Investigators canvassed businesses along Prizheleznodorozhnaya Street, looking for security cameras facing the road. On the facade of the Izopipe factory, they found several cameras, some of which were pointed directly at the roadway.

The first breakthrough came when it was discovered that a camera had captured a person wearing camouflage clothing with a black backpack pedaling quickly along the edge of the road at 7:14 a.m. — after the explosion — traveling from Ryazan toward Rybnoe.

That same day, security forces seized footage from the Astplast, REMZ, and Elkon factories. On Astplast cameras, at 6:33 a.m., a cyclist’s silhouette appeared, moving in the same direction. The face was obscured, and the figure was visible for only eight seconds.

«Як би нам не було важко, нам більше не буде соромно»

Elkon cameras caught another glimpse: at 6:51 a.m., the same silhouette, moving the same way.

«Як би нам не було важко, нам більше не буде соромно»

Footage from the REMZ factory was of no use — the cameras were either pointed inside the buildings or too far from the road to be helpful — but investigatorsnow had three video clips, all showing glimpses of the same cyclist. There was no face or voice, only a direction of movement, clothing, a backpack, and parts of a route. From there, they began “stitching” the route together — linking footage from one camera to the next, from the city streets to the forest belt.

Searching for the guerrilla: “No operationally significant information obtained”

With only video of the cyclist as evidence, security forces began working “blind.” The suspect’s name was unknown, the route was fragmented, and there were no forensic traces — no fingerprints, no mobile phone signals. Investigators began pursuing all possible leads.

In Ryazan, they checked stores with names like “Bratishka” (“Little Brother”), “Russian Fishing,” and “Legionnaire” — places that carried dry fuel, military gear, and electronic parts. One after another, the shopkeepers said they had not sold any such collection of goods, had seen no suspicious customers, and remembered nothing unusual. The same responses came from the chain of “Svetofor” stores, from army supply outlets, and from chemical shops.

Police even pursued leads involving the purchase of a voltage step-up converter — a component that can be used in detonator circuits for homemade bombs. But that trail also went cold: the buyer they tracked down turned out to be an engineer engaged in defense research. His employer confirmed that the device was purchased for official work purposes.

Next came the rental housing angle. Investigators reasoned that the saboteur might have been an outsider who arrived, carried out the bombing, and left. They combed through ads on Avito (Russia’s equivalent of Craigslist), called realtors, compiled lists of short-term rentals, and inspected hostels and even garages. They spoke to garage cooperative chairpersons, apartment residents, and property managers — but found nothing.

They also checked nearby settlements. Investigators combed through the “Kombaynostroitel” dacha cooperative, where, according to one theory, the cyclist might have hidden after the blast. The cooperative had 381 plots, more than 100 of which were abandoned. Only six families lived there year-round. All reported seeing no strangers and receiving no unusual visitors.

Investigators inspected abandoned plots, searched derelict dachas, and checked for any signs of a hidden bicycle. Again, they found nothing.

«Як би нам не було важко, нам більше не буде соромно»

A map of the area Russian law enforcement searched for Ruslan Sidiki.

Special attention was given to Ukrainian citizens. DNA samples — saliva and blood — were collected from displaced persons housed in temporary accommodation centers “Kolos” and “Sazhnevo.” Genetic material was also collected from soldiers stationed at local military units. “The territory is under control. No operationally significant information obtained,” police reports read.

This was not the first act of sabotage in the region. In the summer of 2023, unknown attackers used drones to strike the Dyagilevo military airbase near Ryazan. No suspects were ever apprehended, and the case quickly went cold. Investigators were determined to avoid a repeat of that failure.

The Wagner trace

Investigators also checked former fighters from the mercenary Wagner Group living in the Ryazan region. Their suspicion was hardly unfounded: it was November 2023, only a few months after Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mutiny — and his subsequent death in a plane crash. Questions about the loyalty of returning Wagner mercenaries remained highly sensitive.

Names appeared in the files: Timur Mingazov, Kirill Petrov, and Artem Khozhainov. Security forces examined their residences, social media profiles, and personal connections. One was reportedly in rehabilitation after being wounded, another had not been home for a long time, and the third, according to relatives, was either incarcerated or working at a construction site. All three had combat experience and criminal records. But none of them had been near the explosion site on Nov. 11.

“All that was established was who rents from whom, who has died, and who drinks with whom,” one report concluded.

A retired KGB saboteur weighs in: A careful plan and a clean assembly

For further analysis, authorities brought in a retired explosives specialist, a former KGB reconnaissance and sabotage operative. After reviewing the case materials, he concluded that two explosive devices had been used, placed about six meters apart. Such a setup, he explained, was intended to guarantee the derailment of the train. The explosives used were of standard military-grade power — specifically, TNT — with a charge of no less than 500 grams.

«Як би нам не було важко, нам більше не буде соромно»

Aftermath of the railway explosion in the Ryazan Region.

The retired explosives specialist noted that prior to planting the devices, reconnaissance of the area had likely been conducted. The explosive devices themselves appeared to have been put together in advance, under conditions in which cleanliness was strictly maintained — as indicated by the precision of the assembly.

The specialist’s findings made it clear that the suspect had technical expertise, a solid understanding of how railways were built, and a clear plan — this was no spontaneous act.

«Як би нам не було важко, нам більше не буде соромно»

The specialist’s findings made it clear that the suspect had technical expertise, a solid understanding of how railways were built, and a clear plan — this was no spontaneous act.

Several days into the search, investigators were still largely operating in the dark. The cyclist remained a faceless, nameless shadow. Then, on Nov. 16, another video emerged.

“He's definitely not local”: The guerrilla gets a face

Security cameras on private homes along Sadovaya and Pochtovaya Streets in the village of Perekal had also captured the cyclist. The footage showed the same silhouette, the same steady movement, and the same direction — heading from Ryazan toward Rybnoe. On two recordings taken seven minutes apart, the cyclist crossed the frame and disappeared behind a bend.

At this point, investigators had four video clips — all showing movement in the same direction. It could no longer be dismissed as coincidence.

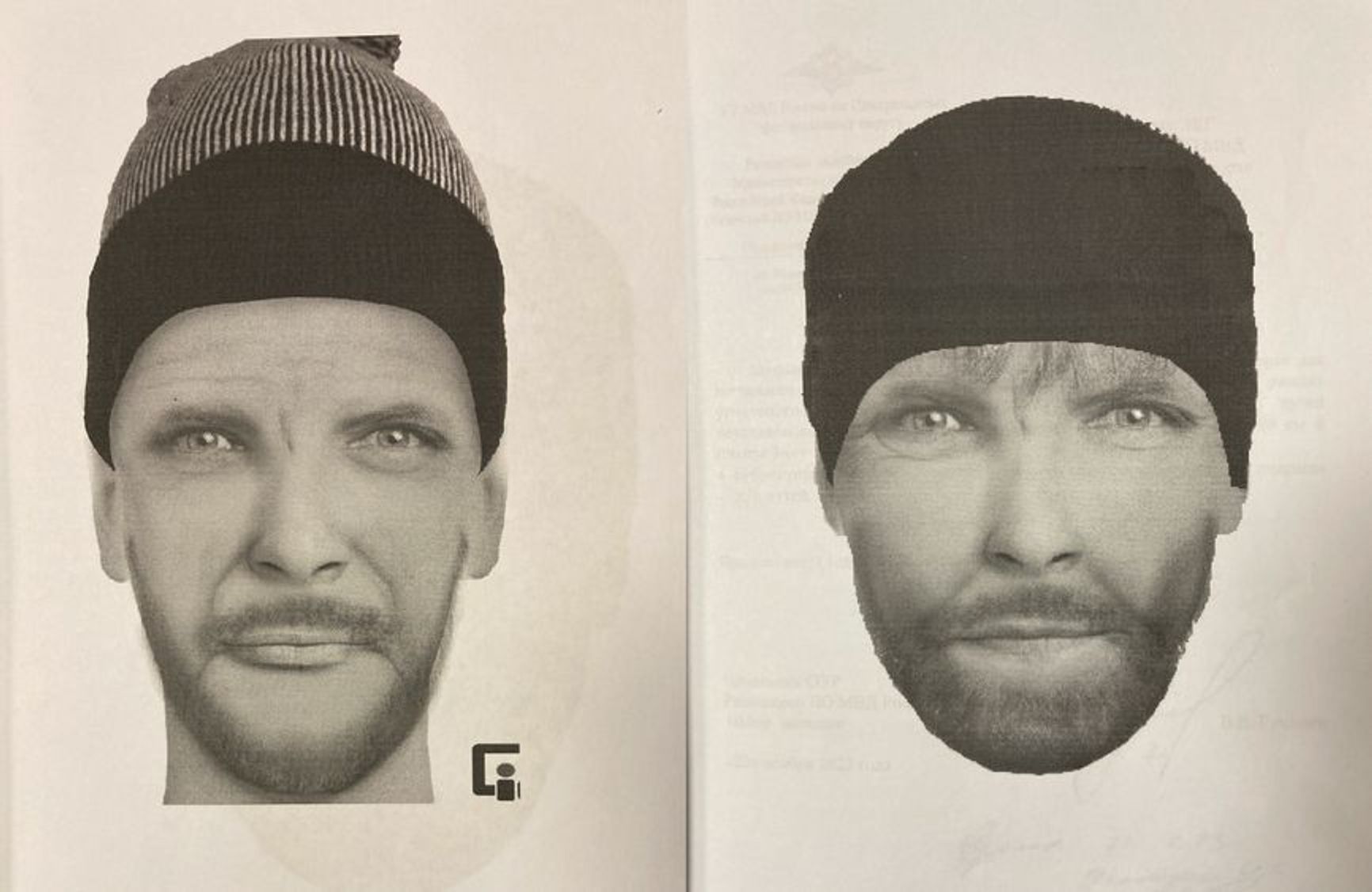

Around the same time, investigators questioned Olga Doronina, a shop clerk in the nearby village of Markovo. She recalled that during one of her shifts shortly before the explosion, a stranger had come into the store. According to Doronina, he was wearing a camouflage jacket several sizes too large and carried a bulky backpack. His hat was pulled down almost to his eyebrows. His face was thin and somewhat triangular, with stubble and light-colored eyes.

“He asked if there was any work available in Markovo. Then he asked if there was a monastery nearby. I told him there was one in Poshchupovo and explained how to get there. He thanked me and left. I never saw him again. He was definitely not local,” the shop clerk told investigators.

«Як би нам не було важко, нам більше не буде соромно»

Using the description Doronina provided, investigators produced a composite sketch — known in Russia as a “photo robot.” The details were sparse: an ordinary face, an unremarkable expression, nothing striking. But it was the first image of a suspect. The investigators finally had a visual reference.

A chance encounter: “I made a couple of mistakes”

The composite sketch did not yield immediate results. Investigators continued going door-to-door — block by block, building by building. Routine questions, brief conversations in entryways: who lives where, who arrived when. Nothing notable. No one expected a sudden breakthrough — the police were simply working through their list of addresses.

Internatsionalnaya Street lies closer to the outskirts of Ryazan — a district of dense apartment buildings, private homes, and nearby fields. It was the kind of area where someone could leave town without appearing on surveillance cameras — or, conversely, lie low without drawing attention.

It was on this street that, on Nov. 29, during another routine door-to-door sweep, a police officer stopped a man coming out of Building No. 13A. Comparing the man’s face to the composite sketch, the officer insisted he accompany him to Police Station No. 4 in Ryazan for questioning. The man agreed.

No one was looking for Ruslan Sidiki at that moment. He was detained purely by chance.

“I made a couple of mistakes. I was in bad shape after my grandmother’s death. I agreed to go with him, hoping they would just ask a few questions and let me go,” Ruslan later wrote from a pre-trial detention center (SIZO) to journalist and human rights activist Ivan Astashin.

Investigative methods: “I was this close to f***ing up every cyclist in Ryazan”

Warning: The following section contains descriptions of torture.

Even after detaining Ruslan Sidiki, the security forces were not fully confident they had the right man. They began questioning him about his whereabouts on November 11. Ruslan’s answers became confused at times, which was enough to deepen their suspicions.

According to letters later written by Ruslan, what followed was torture. Under duress, he confessed not only to the railway bombing, but also to the summer drone attack on the Dyagilevo military airfield — a case that, up to that point, had no suspects or leads. After his confession, the two cases were consolidated into one.

Later, Ruslan’s attorney succeeded in obtaining a medical examination report documenting multiple injuries: wounds to the head and wrists, bruises near the eye, and large hematomas on his back.

As Ruslan recalled, during the beatings one of the officers said: “I was this close to f***ing up every cyclist in Ryazan.”

The human rights project Solidarity Zone published Ruslan’s account of the torture he endured on the night of his arrest:

“A man, about 50 years old, wearing civilian clothes, began telling me that if I didn’t voluntarily confess to the bombing, they would take me out of town and stage an escape attempt to legally justify shooting me — and that before that, they would torture me.

After I agreed to cooperate and give statements, they asked if I had any chronic illnesses. When I said 'no,' someone struck me on the head, and I fell to the floor.

There were at least six people in the office. While I was lying on the floor, they stepped on my arms and legs so I couldn't move, even though I offered no resistance. They pulled up my pant legs around the ankles and tied something to them…Then one of them said to another: 'Call.'

At that moment, I felt an electric shock coursing through my body, causing my muscles to contract in unbearable pain. I screamed loudly and hit my head on the floor. One of them stood in front of me and filmed everything on a cellphone. Because I was screaming, they stuffed a rag in my mouth.

…I cannot say exactly how long the torture lasted; after several electric shocks, my consciousness became blurred. All I can say is that it was unbearably painful.

Between shocks, unidentified people asked me questions. If my answers didn’t satisfy them, they resumed shocking me… They asked whether I was planning another sabotage. I said no — and the torture continued. I realized that to stop the torture, I had to say something — anything.”

Sidiki’s formal arrest was recorded on November 30. All official documents — reports, protocols, and confessions — are dated from that day and make no mention of violence.

Final reflections: “I don’t regret what I did”

Most of Ruslan’s reflections about what went wrong came after his arrest. In letters from the detention center, shared with The Insider by Ivan Astashin, he analyzed his mistakes in detail.

Reconnaissance: “When I was scouting near the railway, I got lazy and decided to bike through the dacha area — just a couple of kilometers from the planned blast site. I ran into a couple of elderly women who could remember me — locals are usually suspicious of outsiders. Ideally, I should have changed my location. But time was short — I had two weeks to prepare, and snow was coming. I decided to stay. It seemed unlikely they would track me down.”

No cover story: “I didn’t come up with a cover story for the day of the bombing. I should have had a clear, rehearsed account of where I was going, why, and when. I didn’t. Even when I was detained, they still weren’t sure I was involved.”

Escape route: “I should not have returned to the city right away. I should have hidden in the woods until dark, then moved out using familiar paths. But I was tired and walked the last kilometer on asphalt, thinking it was safe. That was a mistake.”

Camouflage: “I should have kept my face covered until I got home. After changing clothes, I felt invulnerable — and I relaxed. My clothing should have been more concealing.”

Digital footprint: “After my arrest, they seized my phone and saw my Telegram subscriptions, immediately concluding that I didn’t support the 'Special Military Operation' [Russia’s official euphemism for the invasion of Ukraine]. That was another mistake. I should have looked like an ultra-patriot online.”

Living situation: “I stayed in the city, close to the blast site, and didn’t take any security precautions. If I had set up an IP camera at my door, I might have seen from my smartphone when police came to question my neighbors.”

Interacting with police: “Almost 20 days had passed since the bombing. I had relaxed — and didn’t think twice when I saw a cop outside my building. He compared me to the surveillance footage and asked me to come in for questioning. I agreed.

At the station, they took a saliva sample for DNA testing. Then some plainclothes officers showed up and started asking questions about where I had been on November 11. I got confused in my answers — and one of them realized I was hiding something.

I should have refused to go. I should have insisted they bring a warrant or subpoena. Maybe that would have bought me some time.”

Lack of legal knowledge: “I wish I had better known my rights at the moment of arrest — and understood the methods the security forces use.”

Despite everything, Ruslan considers the fact that he stayed free for almost twenty days to be an achievement — and he believes that sharing his experience could help others.

“Surviving for twenty days shows it wasn’t easy for them. As for the attack on the airbase, they were totally lost. I think my capture can serve as a valuable lesson for other urban saboteurs.”

Despite everything, Ruslan considers the fact that he stayed free for almost twenty days to be an achievement — and he believes that sharing his experience could help others.

«Surviving for twenty days shows it wasn’t easy for them. As for the attack on the airbase, they were totally lost. I think my capture can serve as a valuable lesson for other urban saboteurs.»

“In any case, I don't regret what I did,” Ruslan wrote. “At least now I don't feel ashamed, as I would have if I had done nothing.” His last sentence cited former Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief Valerii Zaluzhnyi: “No matter how difficult it is for us, we will be ashamed no more.”

As of the date of publication of this article (its Russian version was released on April 22) Ruslan Sidiki remains in pre-trial detention. He faces life imprisonment if convicted on all charges.

«Як би нам не було важко, нам більше не буде соромно»