In 2019, protesters in Chile demanded that the country adopt a new constitution to replace the current Pinochet-era document. However, when the left-wing government that came to power on the strength of that movement failed to implement the promised social reforms, voters responded by electing far-right leader José Antonio Kast, who won a landslide victory in December’s presidential election. Kast, the son of a lieutenant in the German Wehrmacht, an admirer of Pinochet, and a friend of Argentina’s chainsaw-wielding president Milei promises economic freedoms for capital and a longer workweek for everyone else. He also favors strict state austerity and a crackdown on migrants.

Content

A landslide victory

In search of the ideal constitution

The most right-wing president since Pinochet

The son of a Wehrmacht lieutenant

Emergency government

“Long live freedom, damn it!”

A landslide victory

The victory of far-right Republican Party leader José Antonio Kast in the second round of Chile’s presidential election did not come as a surprise. Although in the first round he narrowly trailed the Communist Party candidate Jeannette Jara (23.9% versus 26.8%), two other right-wing candidates — Johannes Kaiser of the National Libertarian Party and Evelyn Matthei of the Independent Democratic Union — received a combined 26% of the first-round vote. Immediately after the announcement that Kast would be moving on to the second round against Jara, they declared their support for their ideological peer, effectively guaranteeing his victory.

The gap in the runoff was striking — 58.2% for Kast and 41.8% for Jara. Moreover, Kast won in all 16 regions of the country, something no Chilean candidate had ever achieved. In addition, no Chilean president has ever won with so many votes: 7.2 million out of a total population of 18.5 million. Turnout reached 85% (though it should be noted that, in 2023, Chile reinstated compulsory voting, which undoubtedly boosted voter turnout this time around).

More importantly, these presidential elections laid bare the sharp polarization of Chilean society: many people believed the choice was between communism and fascism. For example, the populist Franco Parisi, who finished third in the first round, called on voters to cast spoiled ballots so as not to put their support behind either option.

In search of the ideal constitution

Why did the pendulum of history swing so far to the right this time? In October 2019, Chile was shaken by mass popular protests — sometimes even referred to as the “Chilean October revolution.” They began spontaneously, sparked by a small increase in metro fares that became the proverbial last straw. The demonstrations escalated into a general strike, with protesters issuing tough political demands that included calls for the president’s resignation, the convening of a constituent assembly, and the adoption of a new constitution. The imposition of a state of emergency by right-wing president Sebastián Piñera only made matters worse: on October 25, 2019, every tenth Chilean took to the streets — nearly two million people nationwide.

The protests were punctuated by outbreaks of violence, carried out both by the Carabineros and by some demonstrators. The grim toll included dozens killed, more than a thousand injured, and thousands arrested. Within a few days, the government withdrew the military from the streets and began a dialogue with opposition political forces and protesters. As a result, a peace agreement was signed mandating a national referendum to choose between adopting a new constitution or retaining the old one — which had come into force in 1980 under the rule of Augusto Pinochet.

The protest wave was a time of broad public mobilization and enormous hopes. Copies of Chile’s constitution sold out in bookstores, and the upcoming referendum was widely discussed — not just by political parties and trade unions, but among neighbors and even football fans. The attempt to adopt a radically new foundational document through a democratic process involving the entire population was a unique event. Political scientists even compared the situation to “direct democracy” in Switzerland.

The attempt to adopt a radically new constitution with the participation of the entire population was a unique event in modern history

The nationwide vote was scheduled for April 2020, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was postponed until October. In the end, 78% of Chileans came out in favor of drafting a new constitution. To write and agree on its text, a Constitutional Convention of 155 members was elected in May 2021. Its composition was dominated by representatives of left-wing forces, with quotas reserved for women and representatives of Indigenous peoples.

By the time the Constitutional Convention was elected, however, the situation in the country had changed. Mass protests combined with the pandemic had shaken Chile’s economy. In 2020, GDP fell by 5.8%, while unemployment rose to 13%. For a country that had recently been seen as an “economic miracle,” these figures were shocking. The idea of protecting social rights began to recede into the background amid more pressing concerns — rising prices, unemployment, crime, and an influx of migrants from places that were even worse off.

Work on the text of the draft constitution continued for more than a year, and it was put to a new referendum held on September 4, 2022. The document turned out to be lengthy (387 articles), difficult to understand, and overly radical — with a clear bias toward political correctness.

Chile was proclaimed a multinational state, and the customary law of Indigenous peoples was to become a full-fledged part of the country’s legal system. Disproportionate attention was devoted to gender guarantees and Indigenous issues, and the document entailed the abolition of the Senate, which had existed since 1812.

The result was a “constitution of minorities,” and the reaction was clear. This time around, 62% of Chileans voted against adopting the new constitution. Thousands took to the streets to celebrate its defeat, waving national flags (thereby emphasizing their opposition to the multinational outlook proposed by the Constitutional Convention).

Most strikingly, many of those who were celebrating the document’s defeat in 2022 had voted in 2020 to draft a new constitution and had cast a ballot in the 2021 presidential election for the left-wing coalition Approve Dignity, led by Gabriel Boric, who defeated Kast by nearly 12%. However, after taking office in March 2022, Boric failed to establish himself as a reformer. The disastrous outcome of the constitutional referendum triggered a political earthquake within the ruling left-wing coalition, which had pinned its hopes on a new constitution as the starting point for sweeping change in the country. Apparently, the left had no plan B for how to carry out urgent social reforms under the old Pinochet-era constitution (and without a majority in Congress). As a result, a second attempt was made to adopt a new fundamental law.

In December 2022, Chile’s political parties agreed to relaunch the drafting of a new constitution, this time without convening a special Constitutional Convention. Initially, a preliminary draft was prepared by 24 experts, 12 from each chamber of the National Congress. They were later joined by 50 members of a Constitutional Council, elected by popular vote in May 2023 and much more right-leaning than the initial group had been.

As a result, the new draft turned out to be even more conservative than the existing Pinochet-era constitution. Chile was again defined as a “social and democratic state governed by the rule of law,” but it was specified that social rights could be provided not only by the state but also by private institutions. This preserved the system of private pension funds and health insurance companies, as well as private universities and schools, thereby entrenching the selfsame social inequality that participants in the 2019 protests had been fighting to end.

The ruling left-wing coalition that had championed changes to the basic law found itself in a paradoxical situation — Pinochet’s constitution was actually ideologically closer to their own views than the proposed alternative now on offer. In the end, the ruling coalition urged voters to reject the new draft, while President Gabriel Boric personally refrained from expressing his opinion.

On Dec. 17, 2023, in the second constitutional referendum, a majority of Chileans (55.7%) voted against the right-wing draft of the basic law. The situation had reached a deadlock, and Boric stated that “the constitutional process did not live up to hopes that a new Constitution would suit everyone.” Efforts to produced a new draft ended.

The results of the two referendums showed that Chileans wanted neither a left-wing nor a right-wing constitution. They wanted a balanced document guaranteeing social rights and grounded in the consensus traditionally characteristic of Chile.

The results of the two referendums showed that Chileans wanted neither a left-wing nor a right-wing constitution

Instead, they ended up with three years of barren political disputes, which led to fatigue and irritation, the loss of hope for a new constitution, and a shift of attention to more pressing problems. This was what Kast capitalized on in the subsequent presidential election.

The most right-wing president since Pinochet

In 2025, José Antonio Kast was nominated as a presidential candidate by the Republican Party, which he founded in 2019. For more than two decades before that, he had been a member of the Independent Democratic Union — historically the Pinochetist party — and served four consecutive terms (2002–2018) as a deputy in the National Congress. During that time, Kast did not introduce a single major piece of legislation, but he did oppose the divorce law and the distribution of contraceptives, called for the repeal of existing abortion legislation, and spoke out against same-sex marriage and anti-discrimination laws.

Kast opposed divorce, contraceptives, abortion, same-sex marriage, and the anti-discrimination law

In 2016, Kast left the Independent Democratic Union, stating that the party had abandoned its founding principles (ultraconservatism in moral matters, a Catholic approach in the cultural sphere, and neoliberalism in the economy) and become too moderate. As a result, he ran for president in 2017 as an independent candidate, then in 2021 and 2025 as the nominee of his own far-right Republican Party.

The resulting swing between extremes has been stark. The government of Gabriel Boric was the most left-wing in Chile since the time of Salvador Allende, and now, José Antonio Kast has become the most right-wing president since Augusto Pinochet himself. Notably, Kast’s political views were shaped to a large extent by the influence of his father.

The son of a Wehrmacht lieutenant

José Antonio Kast is the youngest of ten children in a family of German immigrants. His father, Michael Kast, was a lieutenant in the Wehrmacht who fought at the front and, from 1942, was a member of the Nazi Party. Michael Kast’s party membership card has survived, which is why any attempts to portray the elder Kast as a conscripted soldier who was “just following orders” did not succeed. After the war, Michael Kast destroyed his officer’s identification and in 1950 fled along the so-called “ratline” using forged Red Cross documents — first to Argentina and then to Chile.

Michael Kast and his wife, Olga Rist, settled in the rural commune of Paine, 44 kilometers south of Santiago, where they founded the Bavaria sausage factory. Documented journalistic investigations cite examples of cooperation between members of the Kast family and the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. A full half of the book A la sombra de los cuervos (In the shadow of the ravens), published in 2015 by journalist Javier Rebolledo, is devoted to the Kast family.

It presents evidence of the involvement of one of Michael Kast’s sons, Christian, in police interrogations, and of another son, Miguel, in providing advice to the National Intelligence Directorate (DINA). In addition, Miguel Kast, an economist educated at the University of Chicago, served during the Pinochet dictatorship as minister of labor and later as chairman of the Central Bank.

During the 1988 national plebiscite on whether Pinochet should extend his rule for another eight years, student José Antonio Kast took an active part in the “Yes!” campaign. It was then that he first appeared in a televised advertisement urging voters to support extending the dictator’s presidential mandate. He would later consistently support Pinochet and praise his rule.

Thus, on Nov. 9, 2017, during his first presidential campaign, Kast said on the air of the Tele 13 channel, “If Pinochet were alive, I think he would vote for me.” He went on to say: “I acknowledge certain achievements of the military government… If one looks at this from the standpoint of the country’s progress, setting aside the human rights issue, it is obvious that Pinochet’s government was better for the country’s development than Piñera’s government.”

In addition, José Antonio Kast maintained contacts with Nazi paramedic Paul Schäfer, who founded Colonia Dignidad as a place where fugitives from the Third Reich could find safe haven. Located a four-hour drive south of Santiago, the colony functioned as a state within a state until 2005, and any trace of some people who disappeared during the dictatorship were lost there. Augusto Pinochet visited the colony and even met there with Walter Rauff, the inventor of mobile gas vans, who had also found refuge in Chile.

José Antonio Kast and Paul Schäfer, 2003

In 2017, Kast ran as an independent presidential candidate backed by a group of retired military officers and organizations of relatives of people convicted of crimes against humanity. Kast said that he proudly defended the work of the military government and promised to pardon all military personnel whom he considered to be unjustly imprisoned.

Among those convicted is the notorious Miguel Krassnoff Martchenko, the son of the White Cossack ataman Semyon Krasnov, a brigadier general in the Chilean army at the time of the 1973 coup. Martchenko was sentenced to more than 1,060 years in prison for crimes against humanity, but that did not stop Kast from visiting Martchenko in prison on multiple occasions. During the most recent presidential campaign, Kast was repeatedly asked whether he still intended to pardon Martchenko, but no answer followed.

A lesser-known episode also occurred in 2017 when Kast’s wife, Pía Adriasola, recounted in an interview how, having once decided to postpone a pregnancy, she consulted a doctor who prescribed oral contraceptives. When she told her husband about it, however, he reacted by saying: “Have you lost your mind? That’s impossible.” He then took her to a priest, who told Pía that the use of such pills was forbidden.

It is therefore hardly surprising that Kast has nine children. His eldest son, José Antonio Kast Adriasola, was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in the 2025 parliamentary elections, held simultaneously with the first round of the presidential vote on Nov. 16. He is 32 years old and has a chance of following in his father’s political footsteps.

Emergency government

In 2021, during his second presidential campaign, Kast used a very familiar slogan: “Make Chile a great country.” His sudden success — at least when compared with his first campaign in 2017, when he received 8% of the vote — reflected a shift in the views of much of the population. Both in conservative provinces and among the urban middle class, Chileans were increasingly disillusioned with their leaders due to rising crime and waves of illegal migrants moving to Chile from less prosperous states such as Venezuela, Peru, and Bolivia.

During that second campaign, Kast also proposed abolishing the Ministry for Women and Gender Equality and replacing it with a Ministry for Family Affairs, as well as restricting certain social assistance programs exclusively to married women (despite the fact that such support is particularly necessary for low-income and single women).

However, in the 2025 campaign, Kast somewhat softened his conservative rhetoric and focused on the idea of an “emergency government,” suggesting that in a difficult security and economic situation, ideological and cultural differences are of secondary importance. Moreover, he sought to avoid references to Pinochetism. In his closing speech following the first round, Kast said that the Dec. 14 election would become a genuine plebiscite between two models of society: the current one, which had led Chile to destruction, stagnation, violence, and hatred, and his own project, which promotes freedom, hope, and the country’s progress. In this way, he indirectly justified the anti-communist struggle waged by Pinochet.

On the evening of Dec.14, after his victory was announced, Kast stepped out to address thousands of supporters in a moderate tone. He declared his respect for democracy, for political opponents, and for pluralism while also expressing his readiness to reach agreements and respect for the contributions of his predecessors. However, this conciliatory rhetoric stands in sharp contrast to the initial programmatic statements of his team.

Kast’s conciliatory rhetoric stands in sharp contrast to the initial programmatic statements of his team

But Kast also announced that, within 90 days of his inauguration on Mar. 11, 2026, the implementation of an emergency plan would begin. It consists of four main points: a tax counter-reform, deregulation, restrictions on labor rights, and cuts in government spending.

On taxation, Kast intends to repeal the reform carried out during the second term of Michelle Bachelet (2014-2018). He proposes lowering taxes for medium-sized and large companies and abolishing the personal income tax for business owners. Such an approach would reinforce the regressive nature of Chile’s tax system and entrench the redistribution of income in favor of the wealthiest segments of the population.

In terms of deregulation, Kast’s program is aimed at dismantling existing constraints on the power of capital, with a particular emphasis on loosening legislation in the areas of environmental protection and real estate.

In the area of labor rights, Kast’s team intends to limit the application of the 40-hour workweek law adopted by the government of Gabriel Boric, effectively nullifying the limited progress made by the previous cabinet.

And Kast’s proposal to cut government spending is sweeping — by $6 billion over the course of a year and a half. The scale of this figure immediately raised suspicions, and Kast’s team declined to provide clarifications, saying only that any announcement of cuts to a specific social program would instantly bring people out into the streets.

Thus, the first measures announced by José Antonio Kast amount to a program of harsh austerity. The concrete substance of this program, however, remains opaque. Kast’s future cabinet has already been described as the first democratic government of the Augusto Pinochet regime. In this way, Chileans who forced the dictator’s departure through a referendum vote have, almost four decades later, voted for his return in an updated form.

The first measures announced by Kast may amount to a program of harsh austerity, but at the same time, Chile once again demonstrated an admirably transparent democratic electoral process. Within half an hour of polling stations closing, the result was already known. At 7:30 p.m., the Communist candidate Jeannette Jara conceded defeat, and half an hour later, she personally addressed the winner: “President Kast, you will find support here for everything that is good for Chile.” Immediately afterward, the outgoing president, Gabriel Boric, congratulated Kast by phone.

“Long live freedom, damn it!”

Kast’s victory brought to an end a turbulent six-year period in the country’s development. For many, it meant that Chile’s dream of social change — so vividly expressed in the protests of 2019 — has now been postponed indefinitely. The 2025 election marked the most serious defeat for the left since the restoration of democracy in 1990.

After the departure of Pinochet in March of that year, all democratic governments were forced to operate within the bounds of the possible, moving forward slowly via a series of compromises with the old economic model. Social reforms were carried out gradually and in small steps, without addressing the core problems. As a result, pensions, education, and health care remain in private hands, social guarantees are largely absent, economic growth does not translate into a general rise in living standards, and socio-economic inequality remains near the top of the Latin American tables.

Between 2006 and 2022, power in Chile alternated between the center-left Michelle Bachelet and the center-right Sebastián Piñera (Chile does not allow two consecutive presidential terms). Needless to say, the two political stalwarts were unable to bring about major change or significantly improve people’s lives, after which Chileans took to the streets, sharply swinging the pendulum to the left. But when the radical government proved unable either to adopt a new constitution or to carry out the necessary reforms, the pendulum swung even more sharply to the right. Having rejected Kast at the polls four years earlier, in 2025 Chileans voted for him en masse — largely out of despair, since the choice, as before, was between bad and very bad.

Political map of South America. Left-wing governments are marked in red, right-wing governments in blue

Kast’s election victory is part of a broader rightward turn — in Latin America and beyond. This conservative shift had already manifested itself in Argentina, where Javier Milei came to power in 2023 on a far-right libertarian platform. In 2025, the center-right Rodrigo Paz Pereira took office in Bolivia, breaking with nearly two decades of rule by the Movement for Socialism. In El Salvador, Nayib Bukele won the presidency back in 2019.

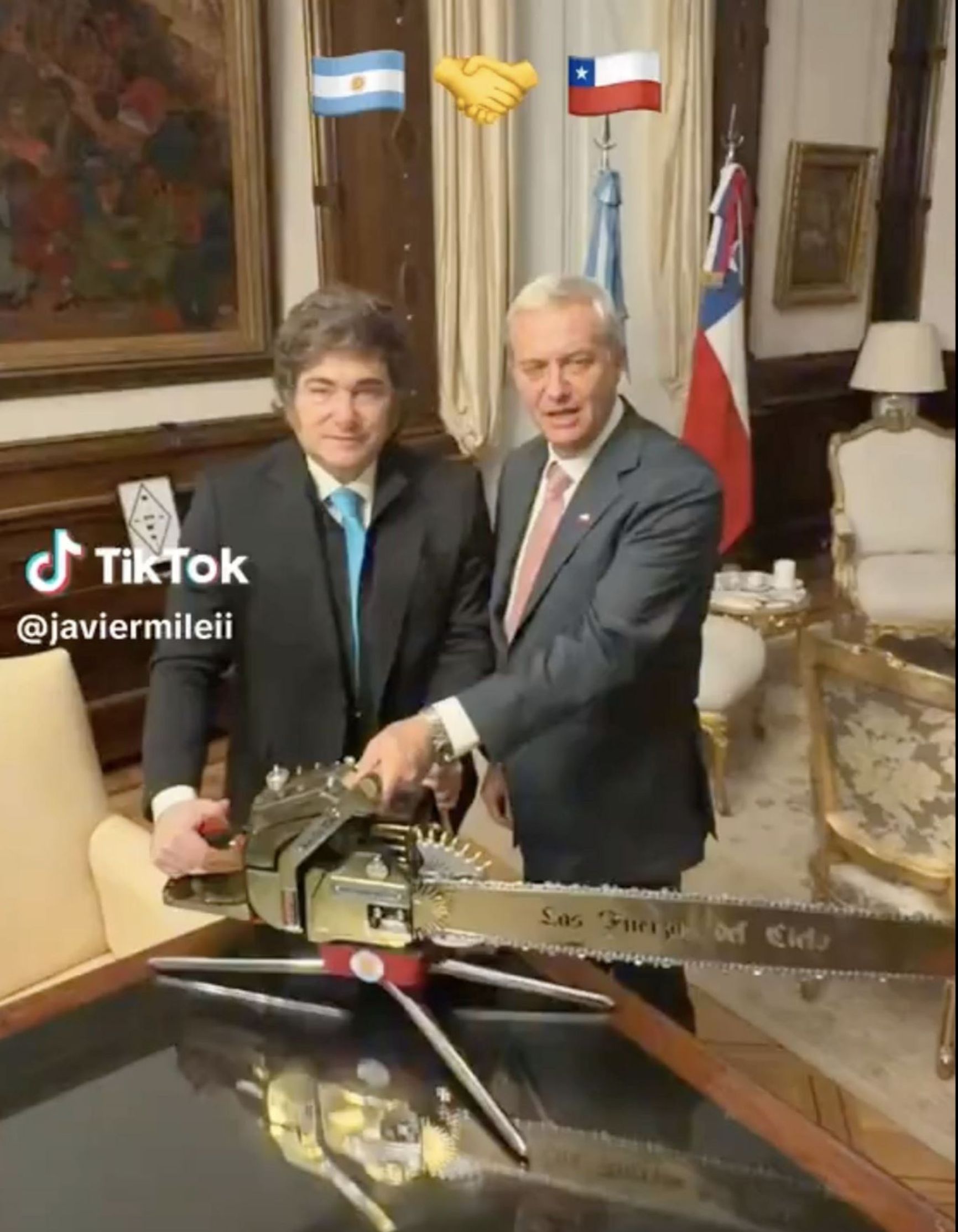

It was no coincidence that Kast chose Argentina for his first international visit in the period between his election and official inauguration, traveling to see his “ideological brother” Milei, who was the first to congratulate him on his victory (the second to do so was U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio). Milei posted a TikTok video in which he and Kast, wielding a chainsaw, declare: “There is one piece of good news: freedom is coming across all of Latin America. Long live freedom, damn it!”

It is possible that Kast’s policies will avoid the extremes of Pinochet’s rule, but they are unlikely to help resolve the problems that drove Chileans into the streets six years ago. He promises to put an end to crime and illegal migration by building new prisons — to complement a proposed ditch and walls along the border.

Undoubtedly, this may make it possible for Kast to achieve a rapid, temporary improvement in the situation, but cuts to social programs and labor rights may sooner or later lead to yet another explosion of discontent. It is still unclear how Kast would behave in such a scenario. Back in 2019, he commented on Piñera’s use of the army to suppress protests: “Gentlemen, none of this will be necessary. Because if I had been in Piñera’s place, none of this would have happened in the first place. There would have been no protests at all.”

Of course, many of the factors that determine any president’s level of success or failure are beyond the control of one politician, or even of one social movement. In Kast’s case, much will depend on the projected growth in global demand for copper, which could lead to increased investment in Chile’s copper industry and have a positive effect on the country’s economy as a whole. The absence of elections in Chile over the next three years will give Kast a certain freedom of action. He will be able to implement his emergency plan until the pendulum of public opinion begins to swing back the other way.