The more than questionable list of wars allegedly ended by Donald Trump since returning to the White House may soon be expanded to include an interreligious conflict in Nigeria. Trump has already threatened direct intervention if Nigerian authorities fail to stop the violence carried out by jihadist groups, whose victims are often Christians. The conflict is growing ever more acute, accompanied by the imposition of sharia law and a humanitarian crisis. The number of refugees is already measured in the millions, and the number of people facing hunger in the tens of millions.

Content

Legacy of the junta

Sharia is not a panacea

Boko Haram

Christians and atheists

Legacy of the junta

Just days after unofficially renaming the U.S. Department of Defense the Department of War, Donald Trump appeared to have already decided which war the revamped agency would start first. “If the government of Nigeria continues to allow the killing of Christians, the United States will immediately stop all aid and assistance to Nigeria and may very well go into this now disgraced country ‘guns-a-blazing’ to completely wipe out the Islamic terrorists who are committing these horrific atrocities,” Trump “said” in an AI-generated presidential address posted on the Truth Social platform.

The trigger for the threats was the mass killings carried out by jihadist groups, after which local priests and their congregations began speaking about a genocide against Nigerian Christians, appealing to the country’s authorities for protection. However, judging by Trump’s post, in his view Nigeria’s authorities as akin to accomplices of the very terrorists the American president is threatening to destroy.

Nigerian officials tried to justify themselves by stating that freedom of conscience and religion in the country is protected by law, that the violence does not have the characteristics of genocide, that not only Christians but also Muslims are suffering from the actions of terrorists and, finally, that the authorities are doing everything possible to stop the violence. Nigeria’s president, Bola Tinubu, even stepped up all official and unofficial channels of communication with the United States in order to prevent a gross violation of the country’s sovereignty and an American invasion.

This, however, was already unnecessary. Trump rather quickly lost interest in what was happening in the distant African country, switching his attention to Venezuela.

At the same time, violence in Nigeria, including religiously motivated violence, has not diminished. On a list of countries where Christians face the most institutional persecution worldwide, Nigeria ranks seventh, ahead of Iran and Pakistan.

The top six states on the list — North Korea, Somalia, Yemen, Libya, Sudan, and Eritrea — have relatively small Christian populations. In Nigeria, by contrast, Christians make up roughly half of the population, and the government is to a large extent composed of Christians and does not engage in persecution on religious grounds. The problem is that two decades ago the state itself limited its own capacities in an attempt to avoid a civil conflict.

In an attempt to avoid a civil conflict, the state limited its own capacity several decades ago

It all began with the collapse in 1999 of the regime of military dictatorship that had been established in Nigeria back in the mid-1960s. During the years of the dictatorship, around a dozen different generals came to power as a result of coups and mutinies. Only two of them were Christians, with all the others being Muslims from Nigeria’s northern states.

Muslims ruled as dictators continuously from 1983 to 1999 and, as is typical of dictatorships, filled senior positions in government and the security services primarily with their co-religionists and people from their home regions. The last of these generals — Abdulsalami Abubakar — returned the country to democracy by holding the first genuine presidential elections in decades and, without hesitation, handing over power to the winner, the Christian Olusegun Obasanjo.

Obasanjo, incidentally, had previously already led the country as one of the “Christian” dictators, but he went into the 1999 election as a democratic candidate, promising to rid the country of nepotism, corruption, and disregard for human rights.

Meeting between U.S. President George Bush and Nigeria’s democratically elected president Olusegun Obasanjo, a representative of the country’s Christian population

The abrupt and radical change in the system of governance led to unrest among the political elites of the predominantly Muslim north. Local officials and governors, many of whom were embedded in the corruption schemes of the successive juntas, feared losing influence, being dismissed, or even facing prosecution.

In an attempt to protect themselves and the established order, they began demanding that the central authorities preserve Muslim identity and defend it from Western influences, which they associated with elections, secular courts, and a Christian administration. Through these actions, they skillfully consolidated the religious segment of society, which saw Muslim politicians as their protectors against secularization or Christianization.

Obasanjo could not dismiss or imprison these Islamic populists without risking a large-scale Muslim uprising, and the politicians themselves had no option but to follow through on their promises and press the central authorities for maximum Islamization of the north. This is what they did, forcing the federal center to agree to the introduction of sharia law in parts of Nigeria.

Sharia is not a panacea

It was assumed that the two legal systems – the liberal constitutional one and the one based on sharia — would exist in parallel, and that punishments such as amputation of a hand for theft or stoning for adultery would apply only to Muslims. However, Christians and followers of traditional African beliefs feared that Islamic laws would also be extended to them. They responded with protests, which were met with hostility by their Muslim neighbors. Interfaith clashes and even outright fighting followed, in which thousands of people were killed.

Restricting the application of sharia solely to Muslim communities proved impossible. It was introduced in nine states in their entirety and in some districts of three more states, which together account for just under half of the country’s total territory. In these regions, non-Muslims were banned from selling and buying alcohol, from publicly performing or listening to music, from openly holding religious gatherings, and often even from sending their children to co-educational schools.

Non-Muslims were banned from selling and buying alcohol, from publicly performing or listening to music, and from openly holding religious gatherings

An appeals system was supposed to ensure that people dissatisfied with the rulings of sharia courts could challenge them in secular courts, but the officials tasked with performing this function turned out to be corrupt and ineffective. As a result, there can be no talk of full-fledged coexistence of two different legal systems. In many regions, sharia has literally displaced the constitution.

The politicians who stood behind the Islamization of the legal system in the north of the country promised that sharia would deal far more quickly and effectively than secular law with Nigeria’s main problems — corruption, poverty, and the unfair distribution of wealth. Nigeria leads the continent in oil production and sales and at the same time regularly tops rankings of the worst countries in the world to live in.

But sharia did not become a panacea. Corruption did not go away, nor did poverty. Moreover, politicians often simply subordinated sharia courts to themselves, turning them into instruments of their own enrichment. Many sharia judges, maintained by local elites or under their influence, handed down (and still hand down) rulings guided not by justice, but by the interests of their patrons.

“Official sharia is a sham, a smokescreen for corrupt politicians. We will bring people real Islamic law,” a preacher named Muhammad Yusuf explained, accounting for the failure of the policy of regional Islamization.

Boko Haram

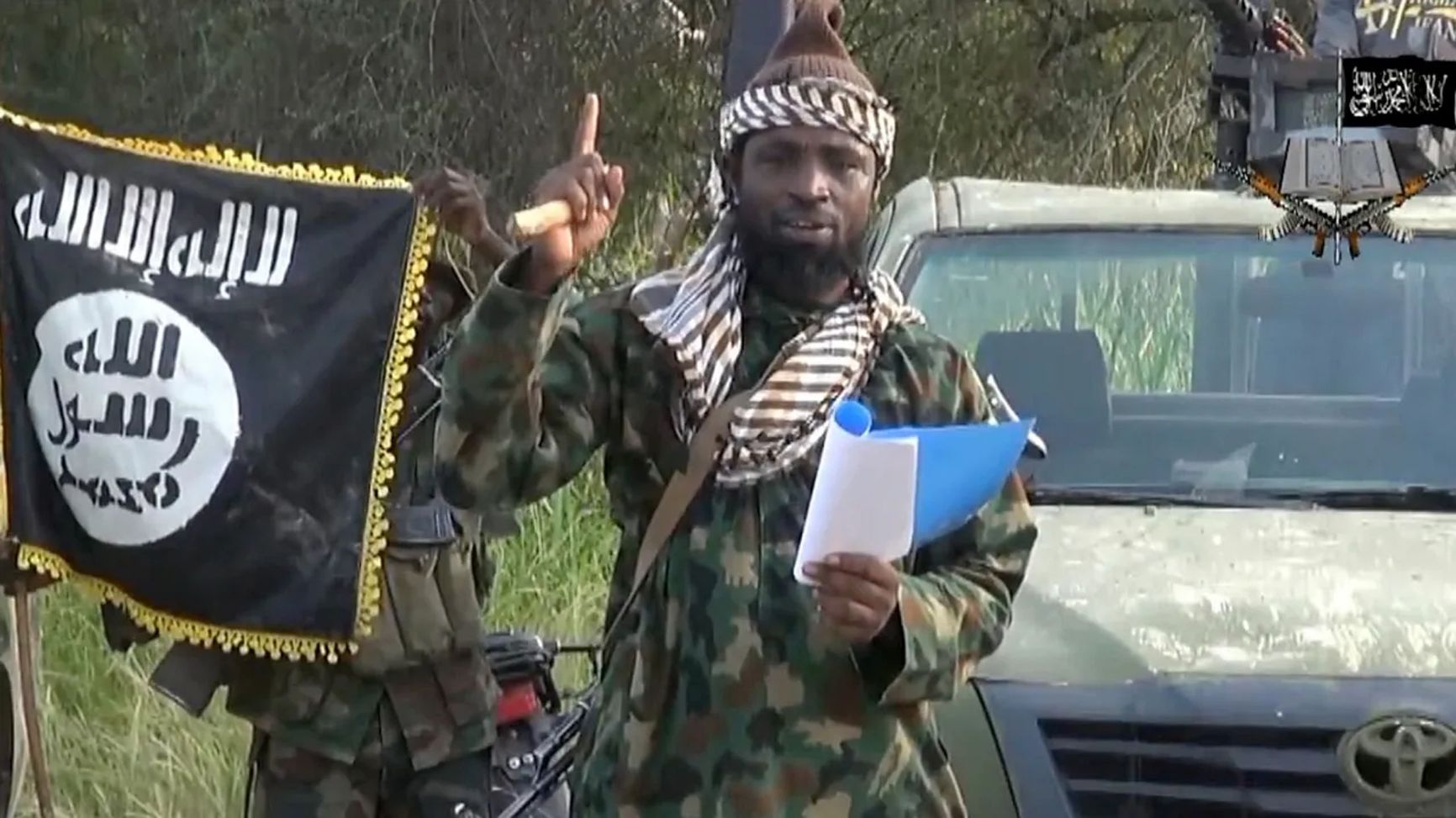

Muhammad Yusuf was fairly well known and popular. He even gave an interview to the BBC in which he said that the Earth is, in fact, flat, and that rain is not the product of the water cycle in nature but a gift from the Almighty. He also opposed schools for girls and was generally dissatisfied with the Nigerian education system. Because of this, Yusuf’s militant followers were even referred to by outsiders as “the Taliban.”

Yusuf’s militant followers were even referred to as “the Taliban”

Nigerians themselves gave the group a different name — Boko Haram. This name is often translated as “Western education is a sin,” but that description appears to be a figurative exaggeration. Boko is most likely derived from the pidgin word book, and “haram” does indeed mean sin, an act forbidden by Islam, meaning a more accurate translation of the group’s name would be “Ban on books.”

Boko Haram emerged in 2002. From the very beginning, it set itself the task of introducing “proper” sharia in Nigeria — not limited by state or district boundaries, and not limited by a parallel secular court system, police force, or constitution. Hostile both to the federal authorities and to the northern Muslim elites, the group had been operating underground from its inception, periodically carrying out raids on police stations or attacks on officials. In 2009, Boko Haram militants attempted to seize control of the city of Bauchi — the capital of the northern state of the same name — launching an uprising against the local authorities. However, the revolt failed, Muhammad Yusuf was imprisoned, and he soon died in custody under mysterious circumstances. But Boko Haram managed to survive the loss of its founder and even to significantly strengthen.

This was facilitated by the group’s rapprochement with ideologically very close branches of al-Qaeda in Mali and Algeria. Nigerians underwent training in al-Qaeda camps, where they acquired the skills necessary to wage large-scale guerrilla warfare. In 2011, after the collapse of Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in Tripoli, Africa was flooded with weapons from Libyan stockpiles that had suddenly been left unattended. A substantial share of these weapons ended up in the hands of Boko Haram militants.

Boko Haram emerged in 2002 and from the outset set itself the task of introducing total sharia in Nigeria

New skills and arsenals, combined with the sympathies of part of the local population, helped the group take control of significant territories in northeastern Nigeria. Poor roads and the lack of communications in these areas also worked in the militants’ favor, making it difficult for the government in Abuja to deploy federal troops. In addition, the military often did not understand whom they were fighting: between raids, the jihadists hid their weapons in caches and blended in with the civilian population.

Boko Haram learned to operate covertly but effectively. After several desperate military operations, Nigeria’s authorities were never able to return the northeastern territories to federal control. They were forced to admit that they were incapable of defeating the group by force and attempted to open negotiations with it, to little effect. Moreover, Boko Haram sympathizers were likely present even in the country’s government.

The fight against the radicals was further complicated by the fact that the “original” Boko Haram was far from being the only jihadist group operating in Nigeria. Essentially, Boko Haram is an entire terrorist “umbrella brand” that is used to describe dozens of large and small groups with similar ideology but headed by different leaders. These groups can enter into situational alliances with one another, but more often they compete among themselves for control over different areas of northern Nigeria. As a result, the weakening of one of them through military operations usually just leads to the strengthening of a rival.

However, the largest and most combat-ready group was always the one originally founded by Yusuf. It was this group that took the conflict in northern Nigeria to a new level by joining ISIS in 2015. From its start as a local group, albeit one cooperating with jihadists from neighboring states, Boko Haram turned into part of the global jihadist caliphate.

From its start as a local group, Boko Haram turned into part of the global jihadist caliphate

The new status brought with it new opportunities. Fighters from other countries began joining Boko Haram. The group, which changed its name to “Wilayat West Africa,” expanded the scope of its operations to southern states and even to neighboring countries, gaining access to the tactical and strategic expertise of other ISIS “branches.”

But not everything went smoothly for Boko Haram. Some commanders refused to obey the decisions of the Middle Eastern caliph, whom they had never seen in person. They broke away from the main organization and for a time even fought against their former comrades.

Overall, the Nigerian group demonstrated a resilience that other regional branches of ISIS could not match. Thus, after the defeat of the self-proclaimed caliphate in Syria and Iraq, Boko Haram effectively became the main and most viable “affiliate” of ISIS. The international anti-ISIS coalition, which remains active to this day, is busy finishing off the remnants of jihadist units in Syria and Iraq and does not venture into the African hinterland.

Under the Boko Haram “umbrella brand,” at least 10,000 active militants are now operating in Nigeria and neighboring countries

Under the Boko Haram “umbrella brand,” at least ten thousand active militants are currently operating in Nigeria and neighboring countries. Several thousand more belong to other jihadist groups that have no historical or ideological ties to Boko Haram. Their activities are financed from a range of sources — taxes that the jihadists collect in territories under their control, customs duties levied on traders bringing goods from other regions of Nigeria, and donations. The money is spent not only on weapons and militants’ salaries, but also on support for poor communities, which ensures local support for the jihadists. The main occupation of ISIS and related groups, however, is of course not charity, but war.

Christians and atheists

Their opponents in this war have traditionally been the military, police, officials, and Christians. The latter have been declared agents of hostile Western influence, enemies of the faith who obstruct the establishment of “true sharia” and therefore must be expelled or destroyed.

In total Boko Haram and its various incarnations are estimated to have killed between 30,000 and 60,000 people — at least half of them civilians, and most of those Christians. Indisputably, millions have become refugees as a result of the group’s actions, which have triggered one of the most severe and protracted humanitarian crises in world history: refugees left without any means of subsistence, economic ties torn apart by guerrilla warfare, production facilities destroyed by fighting, and farmland left uncultivated for fear of coming under fire. According to UN data, around 27 million Nigerians are already undernourished. Next year, according to forecasts, this figure could rise to 36 million.

Nigeria’s president Muhammadu Buhari was the first leader from sub-Saharan Africa to be invited for talks during Trump’s first presidency

Trump, for his part, is focused on just one issue — the killing of Christians by jihadists — saying he is ready to deal with this problem using America’s armed forces. But it is difficult to assess how serious the threat of a military invasion of Nigeria is, and virtually the entire modern history of American interventions — from Vietnam to Afghanistan — suggests that getting involved kinetically is a bad idea. If the United States were to invade Nigeria, it would have to deal with people from an unfamiliar culture, and with combatants who easily blend in with the local population and enjoy its support. Even the highly eccentric Trump must understand all the risks associated with starting another potential “forever war.”

Trump must understand all the risks associated with starting another potential “forever war”

However, it appears that Trump may have a chance to boast of yet another victory without the need to actually physically intervene. In response to threats from the United States, Nigeria’s military command has promised to step up operations against Boko Haram, and in some areas federal forces have even begun relatively successful combat operations against the jihadists. To add another dubious success to his peacekeeping record, Donald Trump will only need to wait for official statements from Nigeria’s military and political leadership announcing the defeat of terrorist groups and the liberation of a number of areas of the country from their presence — even if, in essence, the problem will remain unresolved.