In its early Bundestag elections, the German nation put power in the hands of a black-red coalition made up of the CDU/CSU and the former ruling Social Democratic Party. Interestingly, the country's political preferences are split along the old border between East and West Germany, with the far-right Alternative for Germany triumphing in the east and the Christian Democrats keeping the west. Berlin stands out again for its choice of a third option: the Left, which inherited the legacy of the German Communists. Future Chancellor Friedrich Merz seems resigned to the accelerating deterioration of relations between the U.S. and EU, meaning his government is on the lookout for new international partners. However, political scientist Dmitri Stratievski argues that Germany's Russia and Ukraine policy will remain unchanged.

Content

A fractured society

New coalition: shaking hands without radicals

EU, support for Ukraine, defense: common ground for Scholz and Merz

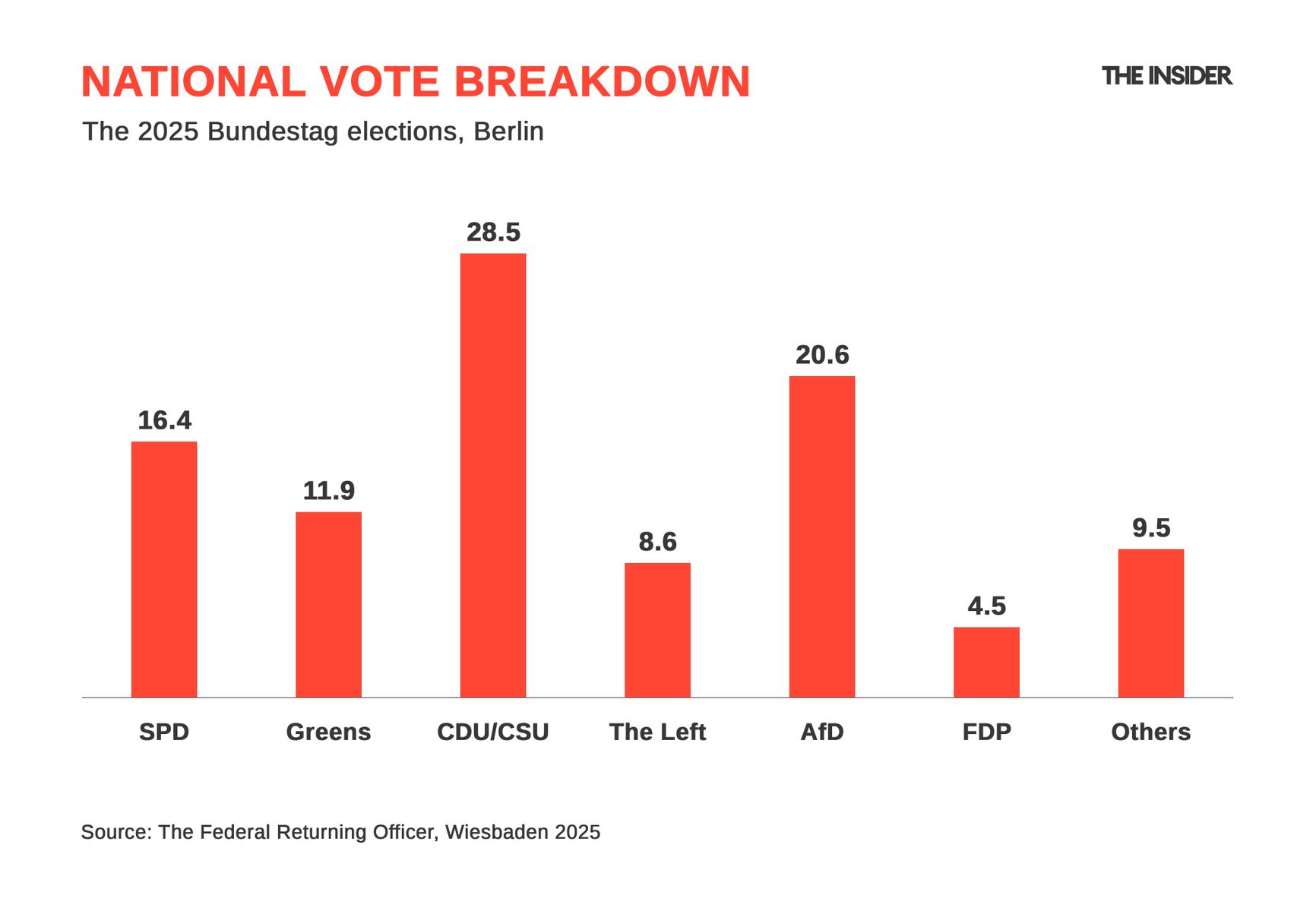

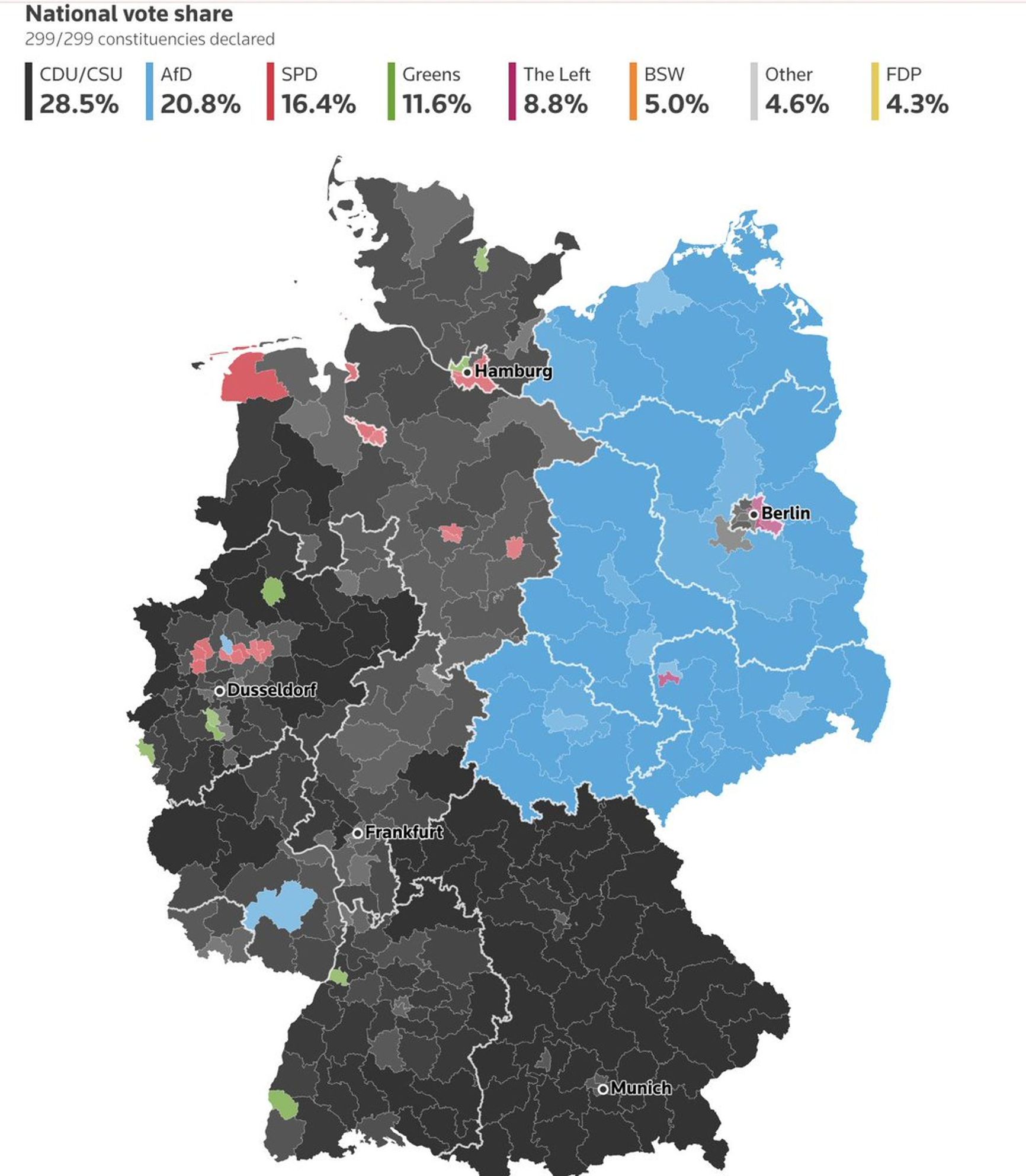

Germany’s snap parliamentary elections of Feb. 23 produced results almost perfectly in line with the latest opinion polls. First place was predictably taken by the conservative Union parties: the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) and the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU), led by the likely future chancellor Friedrich Merz (28.52%). The runner-up, for the first time since World War II, was the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) with 20.8%. The ruling Social Democratic Party (SPD) came in third with their lowest ever result (16.41%). The so-called “traffic light coalition” is now history, giving way to a different format of government.

A fractured society

Today, even an incorrigible optimist can no longer call Germany an island of political stability, where the electoral field is divided among mainstream parties and where radicals remain on the margins of national politics. The first serious crack fractured this “wall of calm” back in 2017, when AfD ran in the Bundestag elections for the first time, winning 12.7% of the vote and becoming Germany's third most popular party. The success on the opposite radical flank was also noticeable, as the Left Party, which back then still included Sahra Wagenknecht's group, won 9.2% of the vote.

In the pandemic year of 2021, when Angela Merkel stepped away from the world of politics, election results showed a departure from radicalism, with AfD's results slumping to 10.3% and the Left falling below the 5% threshold, meaning their only representatives in parliament were those who won in single-member districts. Meanwhile, the 2024 and 2025 elections to the European Parliament and in three eastern German states ended in the success of the AfD, clearly demonstrating a rift in German society.

Traditionally one of the “people's parties,” SPD lost so much ground that it was knocked out of its traditional strongholds in Germany's industrial center. Here, the conservatives took almost all of the constituencies, gaining an estimated 1.7 million former Social Democrat voters.

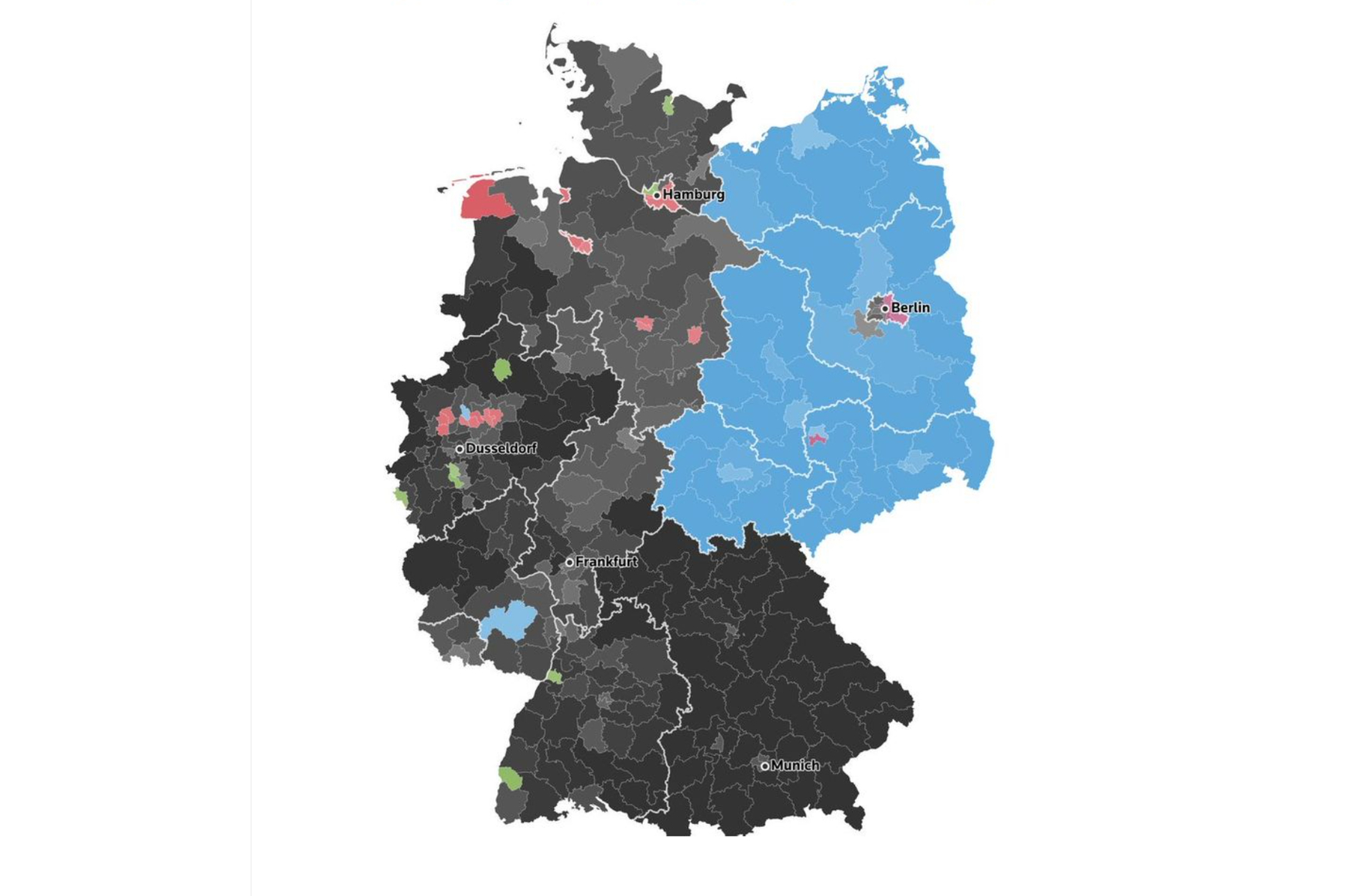

Another 700,000 votes that had gone to the center-left in the previous election shifted to the AfD. Alice Weidel's associates delivered the far-right party's best result since 1933, gaining the trust of 10.3 million voters and triumphing in the east of the country. Admittedly, AfD received some support in West German states as well, but considerably less than in the former GDR.

In all of former West Germany (except the small Saarland), the AfD failed to cross the 20% threshold, with its results ranging from 10% to 15% in Bremen and Hamburg. But its share in the east broke records, ranging from 32.5% in Brandenburg to an all-time high of 38.6% in Thuringia. Only the Christian Democrats and SPD of the euphoric, post-reunification 1990s could boast comparable numbers in the east of the country.

In the east, the AfD is breaking records, winning from 32.5% in Brandenburg to an all-time high of 38.6% in Thuringia

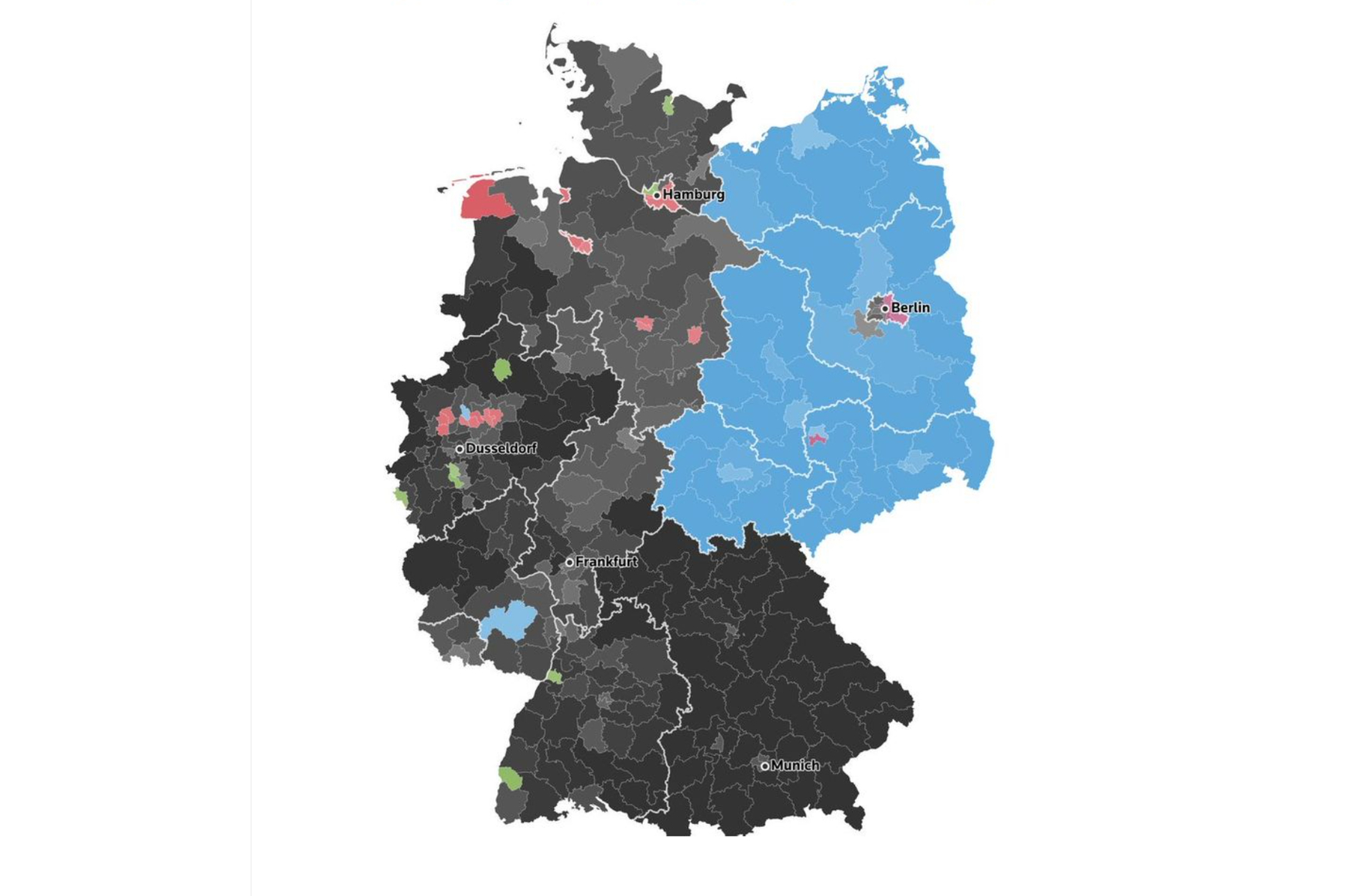

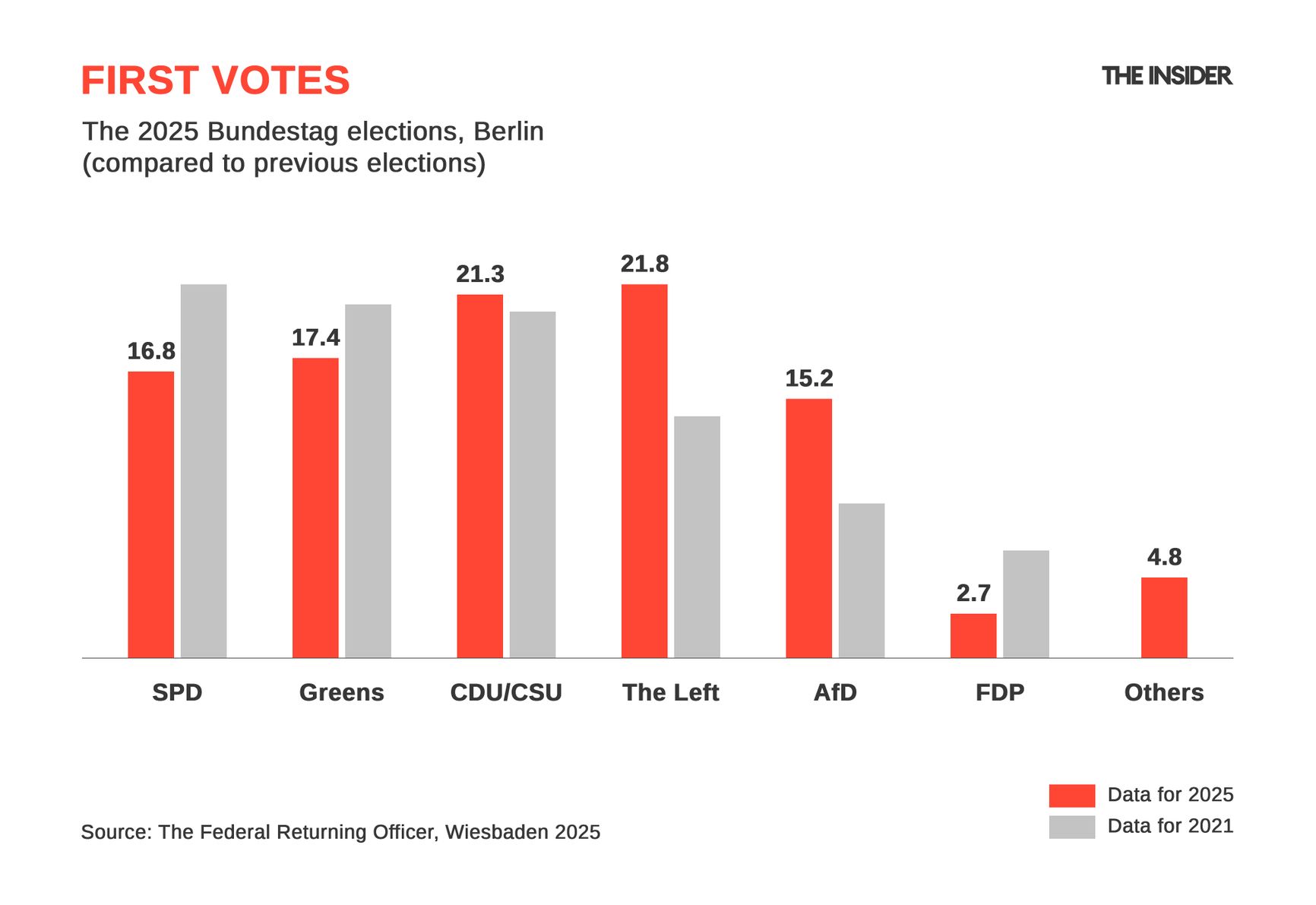

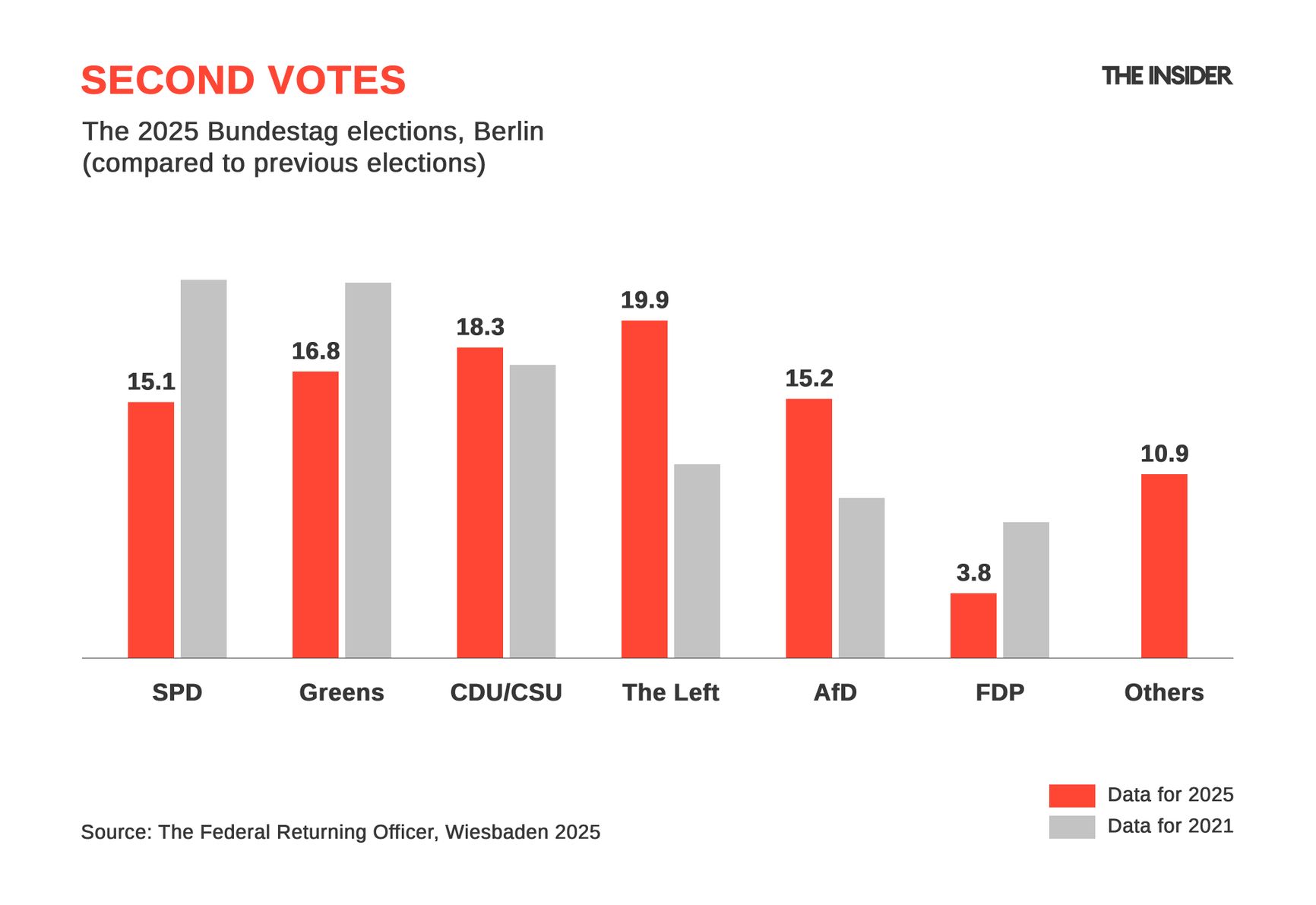

The election results in the capital are paradoxical, as Berlin has traditionally been the fiefdom of the Greens and SPD. In the last state elections, the CDU gained control of the city administration. However, in the Bundestag elections, the Left, which opposed anti-migrant measures and instead emphasized the fight for social justice, came first in both the first votes (for parties) and the second votes (for specific candidates). The Left was also the most popular among people with migrant backgrounds, which is hardly a coincidence.

Bundestag election results for Berlin 2025

As for the AfD, sociologists say there is no single decisive factor that would explain the party's success in eastern Germany. Among the reasons cited are weak political structures, a strong presence of right-wing radicals, the lack of democratic traditions, fears of “your average migrant” in the border regions, perceptions of a deteriorating economic situation, and resentment over the alleged lack of representation of eastern Germans in the federal government.

Differences from the previous elections are also noteworthy. The latest poll suggests that only 39% of far-right supporters are protest voters — those opting for the AfD out of dissatisfaction with the other options on offer. As many as 54% define themselves as staunch backers of the AfD specifically.

Also alarming for the mainstream parties was the fact that more than one-third of the nearly 3.7 million Germans who boycotted the last election cast their lot with the AfD this time around. Germany's electoral map is now almost uniformly colored black in the west (CDU and CSU in Bavaria) and blue in the east (AfD). The watershed runs neatly along the pre-1990 border between East and West Germany.

While AfD's success was predictable, the progress of the Left Party came as a surprise to many. The Left Party, which survived a split, the emergence of the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance, and a series of failures in the 2024 elections, stood no chance of making it to the Bundestag and found itself on the edge of political oblivion. Party strategists capitalized on the missteps of Wagenknecht, who failed to shake off her authoritarian ways — quarreling with influential fellow party members and alienating voters with her anti-migrant and anti-socialist rhetoric.

The Left profited from the slumping ratings of the SPD and the Greens, as well as from the prevailing mood of uncertainty in the left-wing public niche. Eventually, the party ran a successful campaign, doubled its rating shortly before the election, and received 8.77% of the vote. In Berlin, the Left came in first, securing several districts in which the Social Democrats' victory was considered a done deal.

The East-West line is not the only visible fracture in German society. Polarization has become palpable between Germans favoring mainstream policies of past decades and those demanding radical change — even at the cost of authoritarian and inhumane means.

The nation's right turn doubled the AfD's presence in the Bundestag, as the electorate’s small-but-real faction of protest voters teamed up with the far right. The conservatives' victory came not only due to the low approval ratings of Olaf Scholz and the traffic light coalition, but also because of a radicalization of demands in the areas of migration, social security, finance, and the economy, where the bloc played the role of a democratic “AfD Lite.” Merz, for his part, went for the image of “Trump Lite,” a strong leader willing to take unpopular measures in Germany's national interests while playing by the rules of German parliamentarism.

New coalition: shaking hands without radicals

Mathematically speaking, the new five-party Bundestag could feature a variety of coalitions. But only two are politically acceptable: CDU/CSU + SPD (328 seats with a minimum majority of 316 votes) and CDU/CSU + SPD + Greens (413 seats). The first format is already more or less familiar to Germans, as it was actively used under Angela Merkel. However, a majority of only 12 deputies is considered quite shaky in German parliamentary practice. If several deputies are absent from the plenary session or if they break factional discipline for personal reasons, a bill may not be passed due to a lack of votes.

The second model means a comfortable majority, but the positions of the Conservatives and the Greens are very far apart and the alliance could suffer the fate of the traffic light coalition. As a result, a broad coalition of conservatives and the center-left will most likely be formed, even though it will be difficult for SPD leaders to garner intra-party support for it.

In any case, in order to create a workable government, Merz will have to make concessions, especially given the presence of another partner, the Bavarian CSU, which is in many ways more conservative than its all-German ally and makes regional and federal demands that are hardly acceptable to the other stakeholders.

Merz will have to make a lot of concessions to create a workable government

Potential coalition partners will struggle to agree on rules for the entry and stay of foreign nationals, on environmental protection, and on social programs. As for economic growth, a broad coalition will fairly quickly agree to make it the top priority.

Merz wants to author a new German “economic miracle.” Europe's largest economy has slipped into recession, losing its business appeal due to infrastructure problems, an excess of red tape, weak digital technology, and high overhead costs for entrepreneurs. In this regard, all parties agree on the urgent need for de-bureaucratization, a “digital pact,” business incentives, tax reductions, and legislative relaxation. All political forces are equally in favor of upping the funding of the Bundeswehr.

Friedrich Merz wants to author a new German economic miracle

A compromise on fiscal policy is also possible, provided that the CDU agrees to ease up on the country’s “debt brake.” Merz said he was willing to discuss the issue on the day after the election but rejected plans of any sort of “quick reform.” Common steps are also possible in pensions: the older generation is the most consistent group of voters, and politicians traditionally try to “placate” them.

EU, support for Ukraine, defense: common ground for Scholz and Merz

Whereas many domestic agenda items will likely trigger fierce disputes and may be watered down in a future coalition agreement, in foreign policy the parties demonstrate something close to true unity.

Suffice it to cite two politicians' quotes from February this year. One: “Europe is strong. We are the world’s biggest economic area and very successful.” The second: “A strong Europe is an absolute priority for me.” The first statement was uttered by Scholz in the European Council. The second belonged to Merz and was timed with the preliminary election results. Without knowing the authors of the statements, Germans could very well confuse which was whose. Both leaders stand for European unity, the EU's independence from the U.S., the preservation of stability in the eurozone, and closer cooperation among the members of the association. Both Merz and Scholz expressed their readiness not only to strengthen the EU, but also to engage in dialogue with Washington as equals — if necessary, in strong terms.

“A strong Europe is an absolute priority for me,” Merz said after the election results came in

Both the Conservatives and the Social Democrats are ready to continue providing military and economic aid to Ukraine. Even during his forced withdrawal from the political scene after the conflict with Angela Merkel, Merz demonstrated a pro-Ukrainian stance. In his election campaign, he repeatedly offered to expand aid to Kyiv and even to supply the Ukrainians with German Taurus missiles. After winning, Merz reiterated his commitment to supporting Ukraine, invoking the broader need to increase funding and accelerate the rearmament of the Bundeswehr.

The Social Democrats hold similar views. SPD co-chair Lars Klingbeil — the new head of the parliamentary faction and potentially one of the key ministers if a “black-red” coalition is formed — believes it necessary to “efficiently support Ukraine” and criticizes a possible deal between Washington and Moscow that does not involve adequate Ukrainian participation.

Consensus remains on support for Ukraine

Influential politicians of the two parties have reaffirmed their leaders' commitment to a pro-Ukrainian course. Roderich Kiesewetter, CDU speaker in the parliamentary foreign affairs committee and a retired Bundeswehr colonel, sharply criticizes Trump for his “concessions to Putin” and urges alliance members “not to rule out Ukraine's membership in NATO.” Popular Defense Minister Boris Pistorius, who is likely to retain a ministerial chair in the new government, leaves no room for speculation: “Germany will continue supporting Ukraine after the elections.”

There is no ambiguity in Merz's position with regards to Moscow. He has consistently favored maintaining the sanctions regime and calls for expanding it if necessary — a fact that did not go unnoticed in the Kremlin. Shortly after the vote, German media quoted Russian state-owned news agency RIA Novosti as calling Merz a “consistent Russophobe.”

The new German government will advocate a united Europe and will stand ready to provide further assistance to Ukraine. In doing so, Merz will be guided not so much by declared intent as by geopolitical, economic, and financial realities. The U.S. is too important to Germany, and a trade war with Washington would cost Berlin excessively, so the future government will have to find ways to reach at least some form of agreement with Trump.

Under Scholz and Pistorius, Germany's defense budget overtook Britain's for the first time in 30 years, reaching 52 billion euros. But Germany is not in a position to fill the gap if the U.S. withdraws its military aid to Ukraine — or to take on the role of providing Europe with a “security umbrella.” Compensating for a U.S. withdrawal from the continent would require a concerted effort by other EU states with developed military industries, such as France, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Sweden.

Under Scholz, Germany's defense budget overtook Britain's for the first time in 30 years, reaching 52 billion euros

Additionally, the new cabinet cannot ignore the changes in domestic public opinion. According to a recent poll, 46% of Germans are in favor of ending German aid to Ukraine, both military and financial. Among young people aged 18 to 29, 57% are opposed to supporting Ukraine. Merz and his team will have to convince not only foreign allies, but also plenty of their fellow countrymen, of the need to stay on the current course.