Since the beginning of 2023, Russia has experienced a significant surge in the demand for online courses covering astrology, fortune-telling, numerology, and magic. Notably, sales of Tarot cards on Wildberries saw a remarkable 105% increase during the months of January to March, while amulets and protective bracelets witnessed a substantial 95% growth in popularity. Curiously enough, the allure of the occult and esoteric arts was just as fashionable during the early 20th century, during the rule of Nicholas II. In that bygone era, mediums summoned the spirits of deceased emperors for communication, grand duchesses carried holy fools' food leftovers in small pouches, and a Buryat healer made promises of adding Tibet, Mongolia, and China to Russia at the behest of the Tsar.

Content

The common folk and sects

Aristocratic Spiritualists

The Empress's “godly men”

“An elder with an indefinable unpleasant aura”

Nicholas II received an excellent education. The leading scholars of his time—Beketov, Kyui, Obruchev, and others—introduced the heir to contemporary scientific theories (though, of course, they had no right to assess how well he assimilated new knowledge). Nevertheless, with the passing years, the deeply religious man's superstitions and mystical inclinations took increasingly grotesque forms, sliding into a peculiar obscurantism, which somehow coexisted in his soul alongside orthodox Christianity. His entourage, and later the entire country, blamed the empress for this transformation.

As years passed, the deeply religious man's superstitions and mystical inclinations took increasingly grotesque forms

The Emperor's fanatically religious spouse, Alice of Hesse, initially wondered if she could renounce her Protestant faith and embrace Orthodoxy along with the Russian crown. However, once she converted, she became deeply enthralled by Orthodoxy, even more so than by Protestantism.

In the imperial family, daughters were born one after another. After the birth of their fourth daughter, with hopes for a male heir fading, the empress supplemented her prayers with prophecies and sought divine assistance through the guidance of Russian holy fools and foreign spiritualists and hypnotists.

Without concern for the contradiction with canonical Orthodoxy, the spouses increasingly sought answers and aid in mysticism. They kept a company of peculiar individuals, who eagerly accepted their generous gifts and fiercely competed with each other.

The Orthodox Church was not thrilled about these developments but chose not to condemn them. Both the aristocracy and the common people, up to a certain point, looked upon their monarchs' eccentricities with understanding. As the country faced a growing crisis, trust in the Orthodox Church diminished, and the need to find consolation and the promise of a better life after death grew stronger. Fearing the future, people desperately sought those who could predict it. The allure of mysticism and esotericism affected the rich and the poor, peasants and nobles alike.

According to the words of the populist and publicist Lev Tikhomirov, the whole country was “engulfed in some kind of insane psychosis.” Even the “rational individuals” in “positions of power seemed to be under the spell of some incomprehensible sorcery”. Tikhomirov lamented that the “spiritual authority is undermined and disgraced, and it is falling more and more in the eyes of the people.”

The reminiscences and especially the diaries of people from that era help us better understand how they perceived the reality surrounding them.

The common folk and sects

The popularity of various sects notably increased in the early 20th century, although most of them had emerged long before in response to Peter the Great's reforms. According to Maurice Paléologue, the French ambassador to Russia, these sects “strangely revealed the moral indiscipline of the Russian people, their inclination towards the mysterious, their taste for the indefinite, the extreme, and the absolute.”

The diary of the French ambassador to Russia, a theatrical and ballet enthusiast, a man of society and passionate gossip, reads like a captivating work of fiction, causing one to forget about the dreadful consequences of the events described in it. Artist Alexander Benois recalled the French ambassador as “Charming Paléologue, parading before the ladies, radiating charm, and narrating historical anecdotes with great wit.” Paléologue, as remembered by Benois, remained “perplexed by Russia, by its fantastical nature,” yet humorously and in detail recorded the madness prevailing around him.

“The cause of such sects is dissatisfaction with the Church,” wrote historian Mikhail Bogoslovsky in his diary, noting that the only way for the Church to combat these sects was to strive to meet their religious quest while the suffering Christian soul sought “a gentle, thoughtful, and responsive shepherd” to replace the “bureaucrat in charge of the Orthodox department.”

The names of most sects from that time, such as Kulugury, Toptuny [Stompers], Plakuny [Weepers], Skakuny [Hoppers], and Subbotniks, do not convey any meaning to the average reader today. Those that didn't die out on their own were quickly and drastically suppressed by the Soviet authorities; only those who managed to escape in time (often to America) survived, such as the Molokans and Doukhobors.

Perhaps the most numerous sect was the Khlysty [Flagellants], numbering up to two hundred thousand people. It gained fame thanks to Rasputin, who may or may not have belonged to it—more likely, he followed precisely the aspects of the movement that suited him. This sect, prevalent mainly in the eastern part of the country, did not formally break away from Orthodoxy but interpreted it quite liberally.

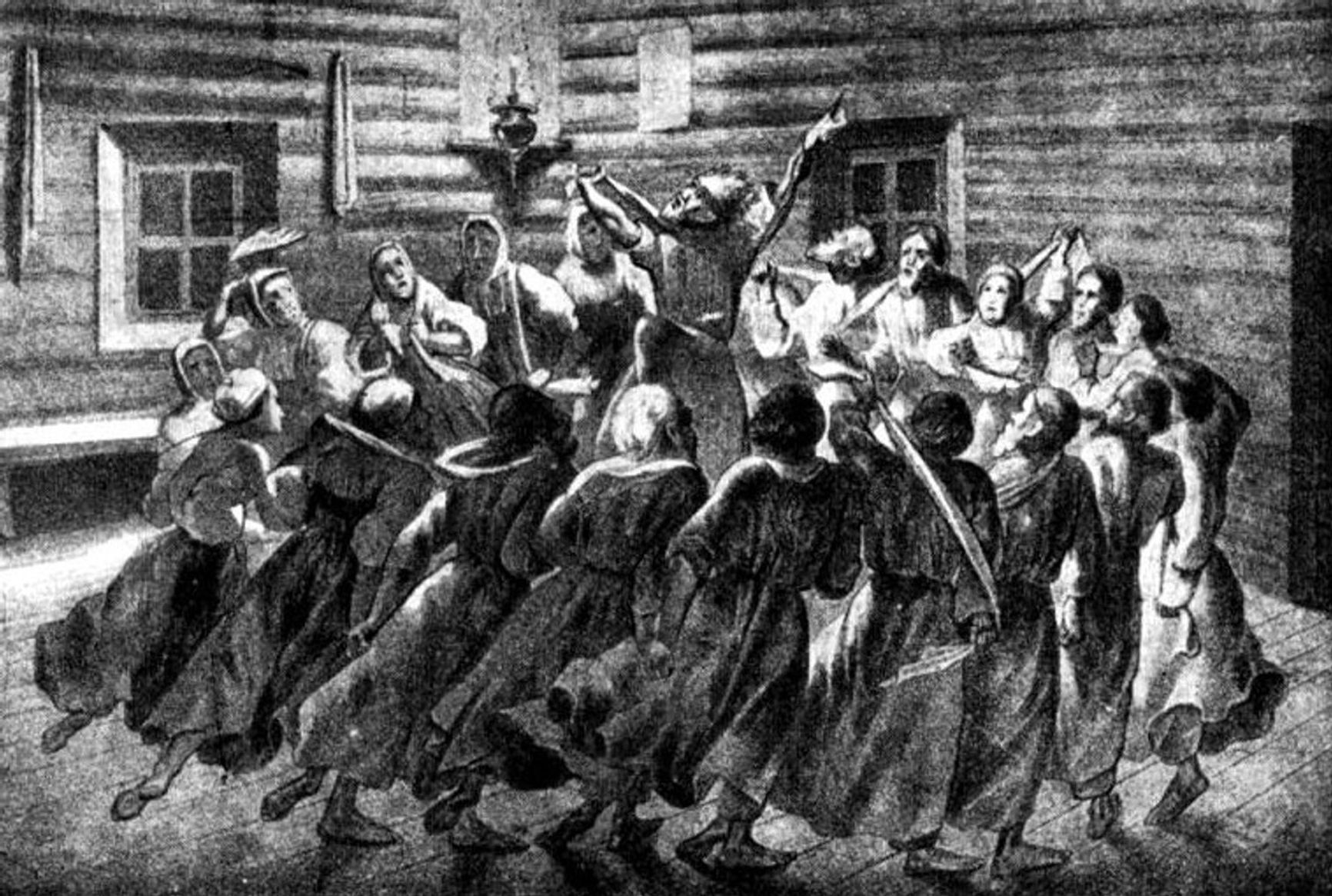

The Flagellants, who were regarded as prophets, would spin and shout prophecies at their gatherings until they fell to the ground, and everyone else would worship them. The writer, historian, and archaeologist Stepan Nechayev described a Flagellant “ceremony” in Polevskoy Zavod, Urals, in his diary:

“Assembling in a cabin, the followers of this sect would undress one of their community members, place them in a corner with outstretched arms in the form of a crucifixion, and light candles in front of them after removing the icons beforehand. In the middle of the room, they would place water, in which they hoped to see or divine what they desired and awaited. They would then run around, flagellating one another while saying, 'Endure for Christ'... Afterward, they would extinguish the candles and had intercourse with one another indiscriminately.”

Gathering of the Flagellants

Wikipedia

Testimonies about the practices of the Flagellants are contradictory. “The liturgy ends with monstrous scenes of lust, adultery, and bloodshed,” wrote Maurice Paléologue in his diary.

Wild rumors circulated about the Flagellants, including allegations of sacrificing male infants and engaging in “ghastly cannibalism.” However, many considered the Flagellants as examples of asceticism and celibacy. Preserving some general traits of the sect, each Flagellant community, or “ship” (as they referred to their communities, which were supposed to save their members when the whole world sank under the weight of sins), established its own rules.

The Skoptsy, who considered themselves one of the branches of the Flagellant movement, resolved the issue of celibacy radically through castration. They called themselves the “white doves.” Their religious services were very similar to Flagellant ceremonies, only without copulation. Those sect members elected as “prophets,” while in a trance, would utter predictions and usually delivered sermons. One such preacher, as described by Nechayev's notes, would make “promises of crowns or eternal life to everyone” after the service, concluding with the exhortation to “deny oneself.”

Nechayev was told about an exceptionally talented preacher who, with his peculiar rituals, could induce such despair in people's hearts that many decided to undergo a horrifying operation. In Nechayev's diary, he mentions two workers in underground mines who were so enthusiastic that they hastened to deprive themselves of “tempting pleasures” right at their workplace, using an iron shovel instead of a block, “placing the edge of an iron cart used to transport ore under them.”

The rector of the church in Berezovsky Zavod mentioned several discovered Skoptsy families in his parish, such as the Korshunovs. The mother of the family confessed to him that she had burned her severed breasts in the stove. As for her husband, “he didn't say where he disposed of his severed member.” Rumors had it that the father of the Korshunov family also castrated himself and died from the wounds.

Although few followed the example of religious fanatics, an undeniable aura of sanctity surrounded them. After the death of the sect's founder, Kondraty Selivanov, who at some point declared himself as the resurrected Peter III, his tomb in the Spaso-Efimiev Monastery in Suzdal became a significant place of pilgrimage. Devotees of this folk saint created small holes in the burial mound and dropped sanctified bread there, without any opposition from the monks.

What was characteristic of that time was that movements that spontaneously formed around popular religious figures, who did not consider themselves sectarians, also acquired sectarian characteristics. Such folk prophets were usually considered miracle workers and healers in addition to their mission of saving souls. Their views, for the most part, tended to be quite reactionary.

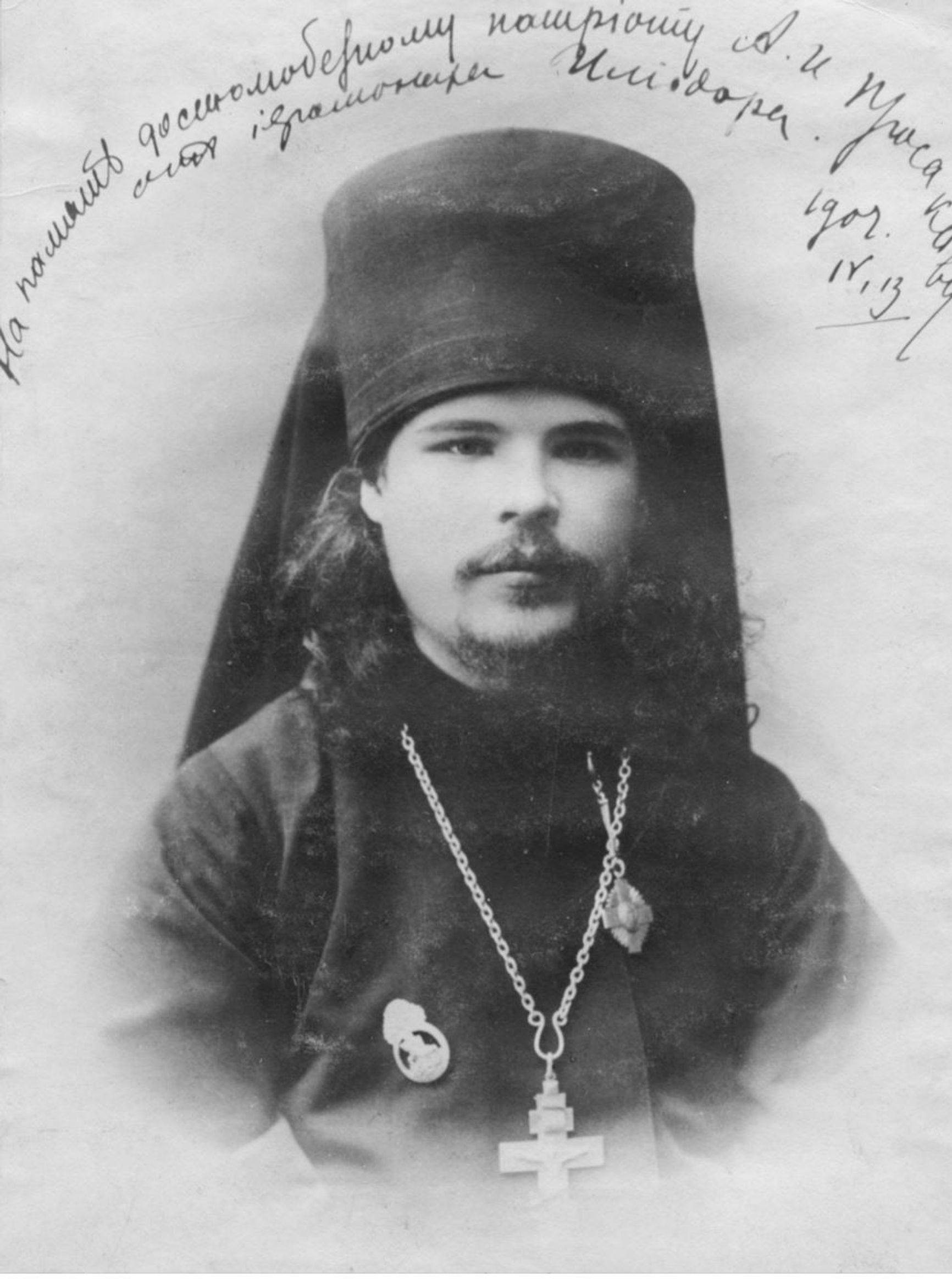

A significant number of followers gathered around the monk Iliodor (Sergei Trufanov), who was passionate about the ideas of the Black Hundred, advocated Jewish pogroms and the struggle against any foreigners, and openly opposed church hierarchs in his writings. A true cult formed around this “monk, blasphemer, rioter, wonderworker, and erotomaniac, adored by the people, a fierce enemy of liberals and Jews.” In Tsaritsyn and Saratov (Iliodor was essentially the founder of the Holy Spirit Monastery in Tsaritsyn), portraits of this imposing monk were sold, along with mugs featuring his image and odes composed by a local self-taught poet named Lvov, who worked as a machinist in the Saratov depot. Crowds of devout believers willingly labored for the well-being of Iliodor's monastery, to which the epithet “martyr” was later added, and they built secret catacombs connected to the church and other buildings with bricks, creating a real fortress in case of either a siege or the end of the world.

Monk Iliodor (Sergei Trufanov)

Later, Iliodor was defrocked, and after the revolution, he worked in the Cheka (the Soviet secret police), but he died not in the monastery but in New York. Despite this, he continues to “heal people” even to this day. In 2018, the monk appeared to a psychologist and astrologer named Natalya Morozova on a forest glade in Volgograd, indicating which herbs she should use for treatment, and allegedly cured her chronic illness. When Morozova returned to thank the healer, a bonfire was burning on that completely empty glade.

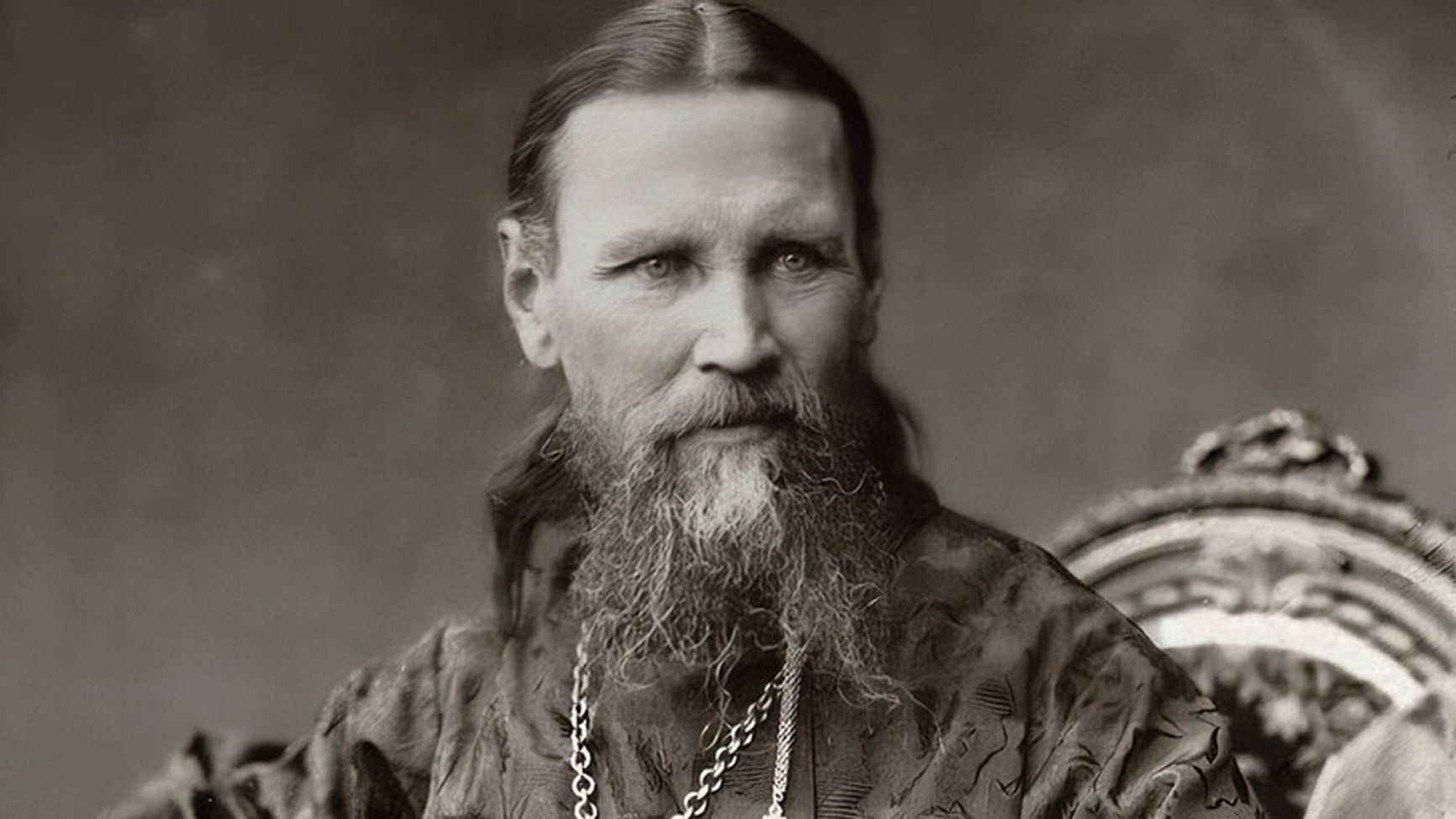

Among the many folk saints of the early 20th century, the figure of Ioann of Kronstadt stands out. While many had doubts about the holiness of Iliodor, the people genuinely revered Ioann of Kronstadt as a saint.

This priest, hailing from a lineage of clergy, dreamed of becoming a monk after completing his studies and joining the missionaries to enlighten pagans in Siberia and America. However, at some point, he realized that people in his homeland needed his spiritual guidance just as much as distant pagans.

The first congregation of Father Ioann consisted of the riffraff in Kronstadt—beggars, criminals, thieves, and drunkards. The humble priest, uninterested in worldly possessions and living a chaste life, quickly became incredibly popular with his hypnotic eyes, which seemed to look directly into lost souls. While he was not well-liked within the church community and was considered a fool-for-Christ, the people proclaimed Father Ioann a wonderworker and a great healer.

He was attributed an extraordinary gift of causing miraculous rainfall in arid areas, restoring sight to the blind, and an incredible number of healings—both in private settings and in massive gatherings of people, even remotely through telegrams or photographs brought to his altar. Later, a multi-volume chronicle of his healings was compiled. He healed both unbelievers and Muslims.

In his book published in 1920 while in exile, the court physician Nikolay Velyaminov also wrote about Ioann of Kronstadt. His account is characterized by sober and healthy cynicism. According to Velyaminov, the “undoubtedly remarkable priest,” although personally religious, was, above all, a talented actor who remarkably managed to induce religious ecstasy in crowds and use it for his own purposes. According to Velyaminov, Father Ioann had the most significant influence on women and less cultured crowds.

It is remarkable that the views of this revered pastor, embraced by almost all of devout Russia, were by no means progressive. The main theme of his sermons was to warn against the perils of revolution. “The Russian kingdom is wavering, teetering on the brink of collapse,” Ioann warned. He despised theaters and journals, considering enlightened individuals as the most heinous criminals, and held a personal enmity towards Leo Tolstoy, whom he described as follows: “Bold, utter godless man, akin to the traitor Judas... Oh, how dreadful you are, Lev Tolstoy, a spawn of a viper.” Tolstoy returned the sentiment in kind.

The common folk worshipped Father Ioann. Thousands of people flocked to Kronstadt daily to attend the service in the cathedral, where, due to the impossibility of individually confessing each worshipper, he introduced the so-called general confession, essentially a sectarian event where crowds of people loudly confessed their sins.

Receiving an incredible amount of donations daily, Father Ioann immediately distributed them to those in need and fed a thousand people every day. Wherever he appeared, a crowd followed. People ran after his carriage and even along the shore after the steamboat during his water journeys. After the death of the beloved holy man, tens of thousands of people regularly came to his tomb.

Among the followers, especially female devotees, of Father Ioann, there were some who revered him as God Sabaoth, although Ioann of Kronstadt himself did not encourage such beliefs. “There were always a few people who entered into religious ecstasy and proclaimed that Father Ioann was the 'Lord Sabaoth' himself, despite the high likelihood of the police catching up with them and removing them,” wrote Vladimir Korolenko in his diary. Newspapers of that time were filled with stories of miraculous healings. According to Korolenko, “certain gentlemen used them for their deviously pious purposes.”

Aristocratic Spiritualists

The high society's inclination towards mysticism strangely intertwined not only with Orthodoxy but also with an interest in contemporary scientific discoveries, fostering the belief that individuals possessing special gifts would become intermediaries to other worlds. The fashion for spiritualism, which originated in Europe, reached Russia with some delay, and séances were often conducted by dubious foreign mediums. Alexander Benois wittily noted that even people who seemed to have the strongest immunity to magic, such as “the most immovable beings in the world, like Orthodox governesses from military families, albeit not of pure Russian origin,” fell for it.

During the first wave of Russian spiritualism, which peaked in the 1870s, leading Russian scientists such as Butlerov and Mendeleev tried to understand whether mediums were genuinely capable of summoning spirits of the deceased and, if so, which processes were involved. The second wave did not delve into profound questions, but it was so widespread that not only the upper class but many merchants and bourgeois also held gatherings around tables lit by red lamps, experiencing discomfort from knowing that such activities were not approved by the church but unable to resist the temptation.

Officer Nikolai Butorov, a graduate of the Imperial Lyceum, extensively described in his diary the spiritualistic séances he attended and the educated public's ambivalence towards them, oscillating between skepticism and the temptation to trust the spirits. When a colleague from the First Department of the Senate invited Butorov to attend a séance by the popular medium Guzek, Butorov agreed out of curiosity, thinking that Guzek was either engaged in some yet-to-be-exposed charlatanism or possessed a strong power of suggestion.

The spiritualist, described as “more than ugly,” was dressed in old-fashioned attire, untidy and somewhat dirty, with colorless cold-steel eyes. He demanded that several heavy paintings be taken off the walls, the mirror be covered, and the piano be moved. Then he carefully wrapped a special red lamp since he found even its light to be too bright.

The participants of the séance sat around a heavy oak table, forming a chain with their hands. During the first two sessions, they only saw some lights and heard vague sounds, grunting, and growling. “After dinner, we sat for the third time,” Butorov later wrote. “No sooner did the lights appear than something crashed and banged on our table. Everyone jumped up. We turned on the electricity – a broken guitar was lying on the table, which had been left on the piano. Thus ended the first evening.” The following evening, Guzek's “imps” behaved more freely. “Shumacher quietly and calmly said, 'Something is sitting on my shoulder... Something cold and soft, like a pig's trotter, touches my neck... It's pressing harder now... Now it stopped.'“

On the third day, the friends experienced the most terrifying séances. Butorov wrote:

“The appearing lights surrounded all of us. The growling and grunting didn't stop, becoming louder and seemingly more malicious. We could hear what sounded like footsteps. Something was sitting on the shoulder of each one of us (for some reason, I remained untouched), and a soft, cold paw kept poking the neck of the person it was sitting on. Suddenly, Avinov let out a hysterical scream: 'It's sitting on me and pressing... Pressing harder... It pinned me to the table...' Avinov was shouting, 'It's strangling me... Help...' We jumped up and turned on the electricity. Avinov's neck was pressed against the back of the chair, and he, deathly pale, could barely stand on his feet.”

During the next séance, Butorov himself almost died of fear when he saw “something larger and rounder, moving slowly down below towards my chair.” Frightened, he jumped up and hurled the chair at the mysterious object. A scream rang out, and some other objects flew through the air. “Everyone shouted, and the lights were turned on. Guzek was sitting there with a bloody face, looking maliciously at us. One of us had a bump on the head, and another had a bruised nose.” It turned out that one of the friends decided to crawl around the table to make sure that the spiritualist was still there, and in response to Butorov hitting him with the chair, he also threw it at someone else.

After failing to receive the proper respect from this group, Guzek decided not to hold any more séances for them. As for Butorov, although the last séance ended comically and everyone later laughed heartily over dinner, he still had a sense of unease from the sessions and saw them as a manifestation of “some dark unknown forces.” He decided not to experiment with them anymore.

While newcomers like Butorov might be frightened and steer clear of spiritualists, many Russian aristocrats in the early 20th century engaged in spiritualist séances regularly. Deeply religious individuals saw nothing objectionable in spiritualism, like the old Countess Ipatievskaya, who had various visions, including those of St. Seraphim of Sarov.

Maurice Paléologue was well acquainted with a circle of royal spiritualists, which later played a fateful role in the country's life by harboring and promoting Rasputin. It included, above all, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, the grandson of Nicholas I, his brother Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich, and the spouses of the two brothers, Grand Duchesses Anastasia and Militsa, daughters of the King of Montenegro. Both princesses showed interest in all things mystical, occultism, and spiritualism from a young age. Militsa received an honorary doctorate in alchemy in Paris. Feeling alienated at the court of the Romanovs, where they were treated with contempt, the sisters became the center of an alternative, mystically inclined circle. Maurice Paléologue characterized this society as “idle, gullible, indulging in the most absurd practices of theurgy, occultism, and necromancy.”

Through the circle, various healers and fortune-tellers found their way to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna as well. Being a foreigner herself, she also suffered from loneliness, which brought her closer to Militsa and Anastasia.

The Empress's “godly men”

The monarchial couple never doubted that their power was given to them by God and that the course of events was preordained. The Empress once said to Finance Minister Kokovtsov, who expressed doubts about his ability to continue the work of the deceased Stolypin adequately:

“I am convinced that everyone plays their role and fulfills their purpose, and if someone is no longer among us, it is because they have already completed their role and should have left, as they had nothing more to accomplish.”

Nevertheless, the couple was deeply concerned about the absence of an heir, believing that having a son was crucial both for their own family and for the state. This led them to seek out various fortune-tellers, healers, and seers in their quest for an heir.

Very soon after the long-awaited birth of the Tsarevich, the spouses realized that their worries would not end there. In October 1904, when the Tsarevich Alexei began to experience prolonged bleeding from the navel, it became evident that he had inherited a dreadful gene for hemophilia from his mother's side, passed down from Queen Victoria's great-grandmother. There was no known cure for this condition. The family's private physician, Dr. Botkin, wrote about the Tsarevich's illness: “There is nothing I can do except to be by his side.”

With this “carefully concealed drama” (as described by the tutor of the Imperial children, Pierre Gilliard), the family became more reclusive. Empress Alexandra Feodorovna herself did not possess robust health and possibly exaggerated her illnesses. Those who knew her personally mentioned, without specifying any particular disease, that at certain moments in her life, she would be bedridden for months, and at other times, she would spend her days in a wheelchair. However, this real or imagined infirmity did not prevent her from getting pregnant five times and giving birth successfully.

Embracing Orthodoxy with all the fervor of her passionate nature and fearing for the fate of the Russian monarchy, her family, and, of course, the incurably ill Tsarevich, the last Russian Empress approached Tibetan healers and French Martinists, magicians and spiritualists, believing each of them in turn with equal passion. It is unclear to what extent Tsar Nicholas II believed in all these individuals, but he knew better than to contradict his wife.

According to the astute observation of Paléologue, the Empress “embraced the most ancient and distinctive elements of 'Russianness,' which find their highest expression in mystical religiosity.” In the French ambassador's view, the “painful inclinations” inherited by the Empress from her mother were also present in other members of her family. Her sister, Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, engaged in active and exalted charitable activities, while her brother, Grand Duke of Hesse, was renowned for his eccentricity. In a balanced Western environment, these qualities might not have been as noticeable, but in Russia, they found the most favorable ground. Paléologue believed that the Empress's extraordinary character traits were not uncommon among the Russian people:

“Spiritual restlessness, constant melancholy, vague longing, mood swings from excitement to despondency, an obsessive thought about the unseen and beyond, superstitious credulity – all these characteristics that leave such a remarkable imprint on the Empress's personality – aren't they rooted and widespread among the Russian people?”

Epileptics convulsed on the floor of her Tsarskoye Selo palace, holy fools uttered incoherent sounds, or, in the best-case scenario, words, while magicians engaged in conversations with the spirit of the deceased Emperor. The rational part of society became increasingly concerned about the influence of all these strange people on the imperial couple and, consequently, on the state as a whole.

After adopting Orthodoxy, the German princess also embraced the holy fools, who were so beloved by the Russian people. One of them, Mitka Kolyaba, a childhood invalid and epileptic, was cunningly used by the monks of Optina Pustyn for their own purposes. Numerous stories about him have survived, all contradicting each other. Some claim that Mitka had two stumps instead of hands, but photographs of him show otherwise. It was also rumored that he had relations with Iliodor and with Father Ioann of Kronstadt, and some even wrote that he became Rasputin's enemy. However, according to other accounts, Mitka was extremely feeble-minded, barely comprehending anything, and completely unable to speak. “He was a typical epileptic with bulging, senseless eyes and a constant dribbling of saliva.”

The monks of Optina Pustyn interpreted Mitka's epileptic seizures and presented them to others as religious ecstasy, a trance – precisely the state in which a person becomes a prophet. It was fashionable to have such a “prophet,” and for the resourceful leadership of the monastery, it could be highly beneficial – as it turned out to be with Mitka. Soon, Saint Nicholas appeared to one of the monks and explained the deep meaning behind the holy fool's cries and convulsions.

Since it was believed that the feeble-minded knew everything about the past, present, and future, in 1901, the monks brought Mitka to St. Petersburg, where he made predictions for the imperial couple until he frightened the Empress too much with an epileptic fit.

As for the famous Pasha of Sarov, who predicted the birth of the Tsarevich, her story is shrouded in mysterious charms. Pasha, known as Irina in the secular world, was a disfigured peasant woman cast out onto the streets by landowners. She lived in the forest for thirty years before finding her way to a monastery. Various prophecies were attributed to her, including the following episode: “Blessed Pasha walked past the fence of the Transfiguration of the Lord cemetery church and, striking the fence post with a stick, said, 'As soon as I bring down this post, people will start to die, so hurry to dig graves.' These words soon came true: when the post fell, Blessed Pelageya Ivanovna passed away, followed by Father Felixov and so many nuns that prayers for the dead were continuously read for a whole year, sometimes two at a time.” The biography of the holy fool contains a rather eerie story about her dolls, of which she had many and with which she constantly played: “And her dolls were remarkable! For instance, there was one doll whose entire head she had washed, and as soon as it was time for someone to die in the monastery, Pasha would take it out, tidy it up, and lay it down.”

Blessed Pasha of Sarov

Nicolas and Alexandra sought answers about having an heir from foreign magicians and seers as well. Through the mystical “sisters of Montenegro,” Militsa and Anastasia, the Empress became acquainted with contemporary European mystical and esoteric trends, so among her “holy people,” representatives of these movements were not uncommon. The person who caused the most concern among the Empress's circle due to his growing influence was a peasant son known as “Monsieur Philippe,” who began his career in a butcher shop.

After appearing at the Romanov court, Philippe Nizier quickly gained such influence that the Tsar granted him permission to wear the uniform of a general in the medical service (previously, Philippe had requested several times to be given a medical degree by the Emperor, but it was impossible due to his lack of education). In February 1903, Pyotr Rachkovsky, head of the foreign agency of the police department, requested confidential information about the past of this “miracle worker” from France with the help of Paléologue, fearing that the eccentric behavior of this charlatan “would end in a terrible scandal.” By that time, Nizier had been playing a significant role at the Russian court for a year.

According to the information gathered by Paléologue, Philippe Nizier-Vachot showed extraordinary inclinations from a very young age while working as a teenager in his uncle's butcher shop. He was passionately interested in magic, predicting the future, and hypnotists. The young man even considered himself one of them. Gradually, people from all walks of life sought help from the healer, including members of high society. Soon, Russian followers also joined his French aristocratic admirers. In Cannes, he was introduced to Grand Duke Pyotr Nikolaevich, his wife Militsa, and her sister Anastasia. Now, the path to the hearts of the august couple was open for him.

“Of medium height and sturdy build, simple and modest in demeanor, with a soft voice, a high forehead under thick dark hair, and a clear, captivating, and penetrating gaze, he possessed an amazing gift for eliciting sympathy and had a striking reserve of magnetism,” wrote Paléologue, who considered Philippe a charlatan, disbelieving that he truly healed the sick in his office using “fluids and astral forces.” The agent of the Security Department, Manasevich-Manuilov, conveyed his impressions of the healer and magician to Paléologue:

“Before me stood a strongly built man with large mustaches; he was dressed in black, looked calm and stern, and resembled an elementary school teacher dressed up for a Sunday. There was nothing remarkable about him except his eyes – blue, half-closed with heavy eyelids, occasionally sparkling with a soft gleam.”

The magician wore a black silk pouch with some amulet around his neck, the purpose of which he refused to disclose to Manuilov. He snored in his sleep, “like a soldier.” His manners, according to Manuilov's opinion, were “humble,” and his reasoning was remarkable. In magic, he was a true expert.

After their first meeting, the imperial couple offered the magician to live in Tsarskoye Selo, where a house was specially prepared for him. Philippe wasted no time and immersed himself in his work, conducting hypnosis sessions once or twice a week. During these sessions, the ghost of Emperor Alexander III, the father of the current emperor, supposedly gave Nicholas II many pieces of advice on governing the state. Philippe also made prophecies and conducted experiments involving reincarnation and black magic.

He promised the couple his assistance in solving their most pressing problem—the lack of an heir. The French magician was not afraid of grand challenges and set to work, “combining the most transcendental methods of magical medicine, astronomy, and his own intellect.” Sources vary: some claim that the empress's subsequent pregnancy turned out to be false, merely a suggestion from the “man of God,” while others say she suffered a miscarriage. Regardless, enemies and those envious of Philippe began to speak out, stating that he had an “evil eye” and that he bore the mark of the Antichrist.

Despite receiving information from the French police about three judicial sentences handed down against the great magician, Rachkovsky was unable to definitively remove Philippe from the court. Only when his prediction of a decisive victory for the Russian army in the war with the Japanese turned out to be catastrophically false did the emperor's enthusiasm for him cool off. The French magician was finally expelled from Tsarskoye Selo.

As one of his aristocratic interlocutors remarked to Paléologue, “The kingdom of absurdity knows no bounds.” One “man of God” had to be replaced by another at the court.

Several years passed, and the concerns about the lack of an heir for the imperial couple were replaced by immense and justified fears for Tsarevich Alexei. With the official medicine being powerless, several charlatans were one by one involved in his treatment, the most famous of whom was undoubtedly the Tibetan doctor Badmaev. This Buryat healer, known for using herbs, powders, and allegedly shamanism, gained incredible popularity in St. Petersburg.

As Paléologue noted with interest, “the Buryat, who had no medical education, openly treated people with his strange medicine, combined with witchcraft.” Although Badmaev repeatedly stated that he had nothing to do with shamans and only treated with his self-made herbs and powders, he earned the reputation of a shaman during turbulent times, which helped him gain popularity. The Tibetan doctor did not charge money for his treatments but preferred to have unconventional clients. For instance, one of his patients helped him at the end of the Russo-Japanese War by organizing a mission to Mongolia, where Badmaev was supposed to meet with members of the ruling dynasty. The mission was carried out brilliantly. However, a small detail emerged later: the two hundred thousand rubles allocated from the treasury for the Mongolian rulers never reached them. Yet, the matter was settled by the same or another high-profile patient of Badmaev's, and as Paléologue wrote, he “calmly returned to his Kabbalistic practices.” In contrast, there were even rumors that the Tibetan doctor brought back various “medicinal herbs and magical recipes” obtained from Tibetan sorcerers during his travels in Mongolia.

Although Badmaev spent most of his life in St. Petersburg, his heart and interests remained in his homeland. He assisted in Orthodox missionary activities among the Buryats, improved the local breed of horses, developed gold deposits, and predicted Russian dominance in the Far East to the Russian crown.

The rumors about Badmaev were incredible. As Paléologue wrote, Badmaev, “strong in his ignorance,” took on the most difficult and obscure medical cases without any fear. If the rumors were to be believed, the medicines he “fancifully named” as Nirvritti powder, Nienshen balm, or essence of the black lotus were actually concocted by him from components obtained from the apothecary. “He claimed to know the ancient healing secrets of the Dalai Lama's land. There is no doubt that this man possessed an immensely convincing gift,” wrote Alexander Kerensky about Badmaev.

Neither the herbs and powders nor the power of Badmaev's persuasion could alleviate the suffering of the heir afflicted with hemophilia. Had his treatment been effective, this intelligent, cunning, and ambitious man could have influenced the course of history. However, the Tsarevich continued to be ill, and the “godly men” at the Romanov court continued to replace each other.

“An elder with an indefinable unpleasant aura”

In the days of Great Lent in 1903, Grigori Rasputin, the new 'godly man,' arrived at the Nikolayevsky Station in St. Petersburg with letters from his patrons, Mikhail and Khrisanf, from Kazan. The already mentioned Iliodor recounted his first appearance in the capital:

“Grigori was dressed in a simple, cheap, gray-colored jacket, with the greasy and dragging front flaps resembling two old leather gloves; the pockets were bulging, and the trousers were of the same quality. Particularly disgraceful, like an old, worn-out hammock, the seat of the trousers swung about; the hair on the 'elder's' head was roughly tied in a knot; his beard hardly resembled a beard at all, but looked like a piece of matted sheep's wool glued to his face, adding to his ugliness and repulsive appearance; the hands of the 'elder' were crooked and unclean, with plenty of dirt under the fingernails, long and slightly bent inward; the entire figure of the 'elder' emitted an indefinable unpleasant aura.”

As time went by, this strange figure became increasingly prominent and distinct from the general mystical haze. He swapped the gray ragged clothes with saggy seat for pleated trousers, silk shirts, and polished boots, gaining entry into the circles of industrialists, bankers, aristocrats—and even the royal family. For a time, no one attached much importance to this 'elder.' However, his influence on the future course of Russian history is well-known.