Russia’s economy entered 2026 weaker than it was a year before, with growth declining and oil prices well below budgeted projections. Combined with a strong ruble, this confluence of factors is expected to widen the federal budget deficit yet again. If oil prices do not rise, something analysts do not expect, Russia’s National Wealth Fund (NWF) could be depleted by the end of this year. If the country’s savings do run out, the government would still be able to borrow from the domestic population, but not without fueling a new round of inflation. An excessively strong ruble is also likely to lead, sooner or later, to a devaluation, which in turn could trigger another spike in prices. For households, businesses, and the state, 2026 is expected to be a year of increased austerity. The public has already felt the impact of higher taxes and prices, and regional authorities are bracing for a prolonged slowdown. Meanwhile, the Central Bank is expected to maintain elevated interest rates, not only to curb inflation but also as part of an effort to shift resources from civilian sectors to the military.

Content

Sharp slowdown

An oil-and-gas-sized hole in the state budget

What happens when the National Wealth Fund runs out

Regional depression

Worse times ahead

Sharp slowdown

As previously reported by The Insider, Russia's official growth figures reflect a statistical sleight of hand from the government — in fact, the country has been in recession since the start of the full-scale invasion. With military factories operating intensively while civilian production stagnates, any reported expansion reflects output that is simply destroyed on the battlefield without creating any actual consumer value.

Now, however, even official figures are approaching zero. Russia’s economic growth slowed to around 1% in 2025, down from 4% a year earlier. The Economy Ministry forecasts growth of 1.3%, the Central Bank of 0.5% to 1.5%, and the World Bank and International Monetary Fund anticipate a figure of 0.8%.

Expectations have already taken a downturn, with officials, bankers, and analysts having repeatedly lowered their outlooks not only for growth but also for wages and consumer demand. The Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting said the situation in Russia’s economy had “noticeably deteriorated” by the third quarter of 2025 and warned that the sharp slowdown in growth, alongside relatively high inflation, had brought the economy close to stagflation for the first time since early 2023.

The defense industry, supported by state orders, continues to grow faster than the overall economy. Output in civilian manufacturing sectors, however, has stopped growing and is stagnating.

Idle equipment is increasing as capacity utilization declines across the economy. Utilization has fallen to about 78% overall and to roughly 70% in manufacturing. Even the defense sector may not be able to prevent a recession, analysts warn, including due to a sustained slowdown in the growth rate of real GDP. Any downturn could prove to be prolonged.

Price growth is expected to affect everyone. An early-year surge following an increase in the value-added tax from 20% to 22% has already been recorded. In the first 19 days of January alone, prices rose 1.7% compared with December. Annual inflation reached 6.47% as of Jan. 19 — higher than in December. “Some companies began adjusting prices back in December, but the main impact is still ahead,” warned Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina. She added that the additional indexation of housing and utility tariffs and other regulated services is expected to have pushed January prices higher as well.

Since the beginning of 2025, production quotas have increased by 2.7 million barrels per day, of which 80–90% have actually entered the market.

In early 2026, Russia is expected to see inflation accelerate due to an increase in VAT.

The Central Bank expects price growth to slow moving forward as higher prices cool demand, but even with the early-year spike, the regulator considers the tax increase preferable to the alternative of expanding the budget deficit.

Under current conditions, lower inflation would not necessarily signal improvement. The recent decrease in inflation appears to reflect weak demand, as prices for nonfood goods have stabilized amid profitability problems in manufacturing.

Some goods have become so expensive that household incomes cannot keep pace and consumers are no longer buying them. Producers, seeing weaker demand, are holding prices steady at the expense of their margins. As a result, household consumption, previously the main driver of the civilian economy, is unlikely to support growth going forward.

The Central Bank’s high interest rate is effectively dividing the economy into “priority” and “secondary” sectors. With resources scarce — initially labor and production capacity but now also foreign technology — various sectors compete for access to a shrinking pool of inputs. If credit were cheap, both civilian manufacturers and defense plants would compete for the same workers and materials, potentially fueling hyperinflation.

Instead, the high rates push civilian sectors out of the competition. Small and medium-sized businesses, developers, and consumer goods producers are reducing borrowing and scaling back expansion plans as financing costs rise. As that happens, their resources, labor, raw materials, and energy, become available elsewhere. The defense industry, by contrast, operates outside market conditions, receiving direct budget funding through state orders and advances or subsidized loans under special programs.

Households are also part of this system. “The state is trying to limit consumption in the civilian sector to free up resources for financing the military sector,” economist Tatyana Mikhailova told The Insider. “High interest rates that attract citizens’ savings to banks simultaneously force them to cut consumption. This is essentially a system of indirect borrowing from citizens so the state can finance the war.”

An oil-and-gas-sized hole in the state budget

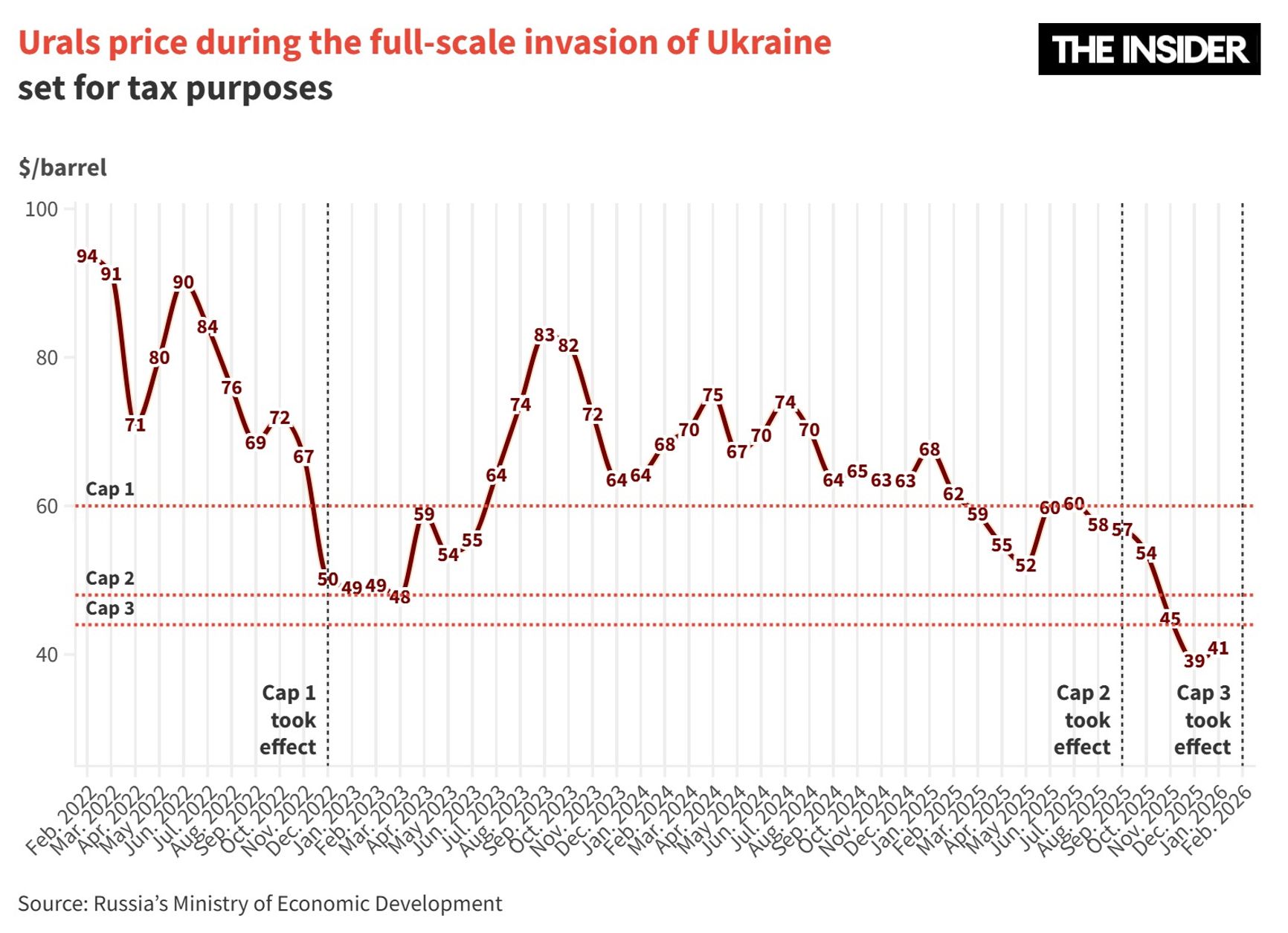

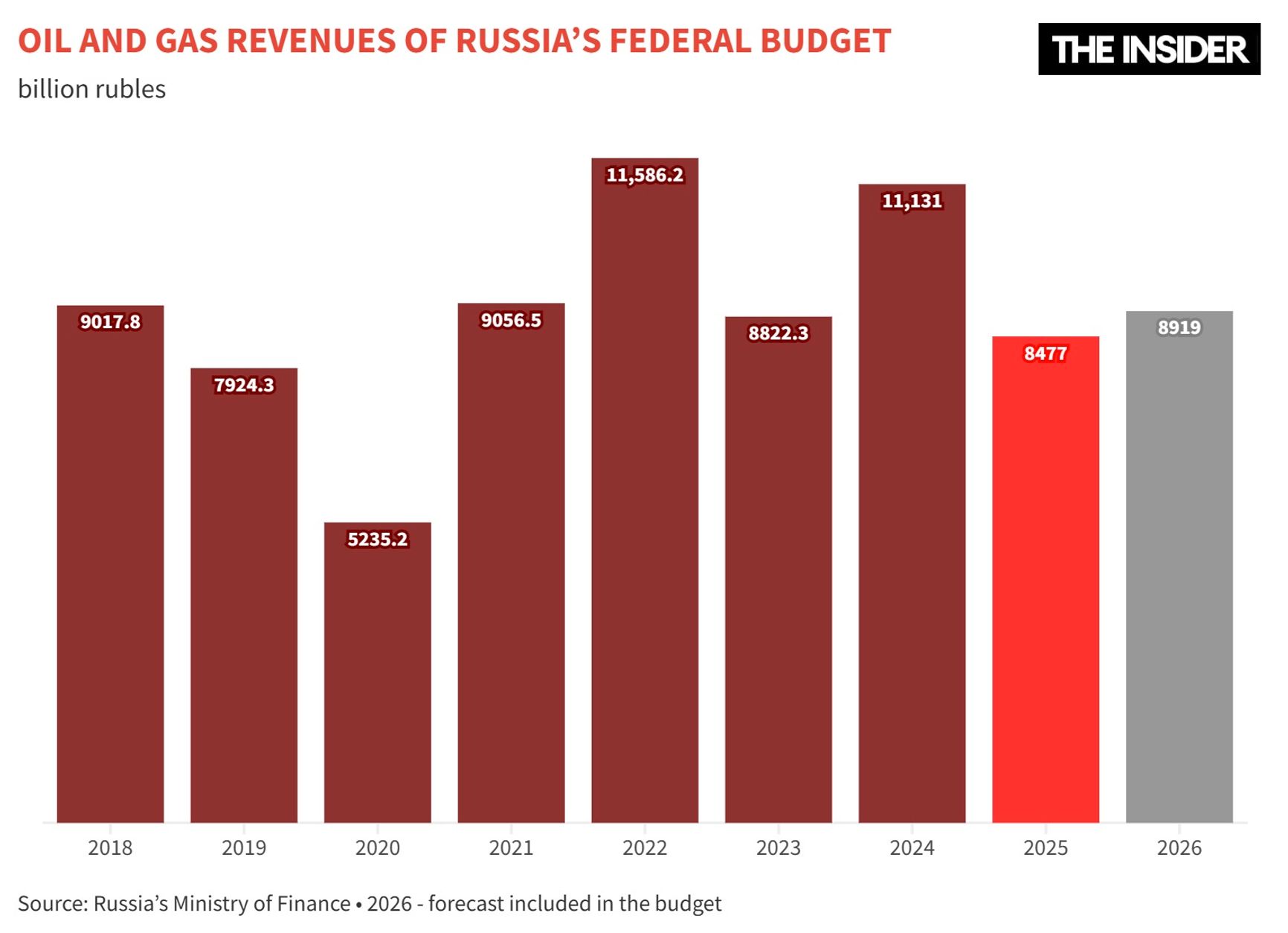

The federal budget is expected to run a deficit in 2026. Under the plan, it will amount to 3.8 trillion rubles, or 1.6% of GDP. However, revenues depend heavily on oil prices, with oil and gas income accounting for about one-fifth of the resources available to the federal budget. The government expects to collect more money than last year, projecting 8.9 trillion rubles in 2026 compared with 8.47 trillion rubles in 2025. These expectations are based on an optimistic oil outlook. The budget assumes a price of $59 per barrel for Urals crude, significantly higher than the $39 per barrel used for December tax calculations. In effect, the government is counting on a substantial increase in oil prices, even though analysts expect the opposite.

Since the beginning of 2025, production quotas have increased by 2.7 million barrels per day, of which 80–90% have actually entered the market.

The Russian government drafted the budget while counting on a substantial increase in oil prices, even though analysts expect the opposite.

Global oil prices fell 19% in 2025, with the average price of Brent crude declining from $82 to $69 per barrel. The drop reflected weaker-than-expected demand growth and increased production by OPEC+. In 2026, prices could fall further as China’s economy slows, reducing fuel demand, while U.S. President Donald Trump’s protectionist policies weigh on global growth. Additional supply may also come from Venezuela, after the United States agreed to imports of 50 million barrels. OPEC+ countries also plan to continue increasing output. Overall, the U.S. Energy Information Administration said it expects Brent to average about $55 per barrel in the first quarter of 2026 and to remain near that level through the year.

Since the beginning of 2025, production quotas have increased by 2.7 million barrels per day, of which 80–90% have actually entered the market.

“A decline in oil and gas revenues could significantly hit Russia’s budget. How it will balance its books is a big question,” economist Sergei Aleksashenko explained on an episode of The Insider Live. “Spending cuts are likely, but not in the military sector,” said economist Ruben Enikolopov, a professor at Pompeu Fabra University. “Even if a peace agreement is signed, production will continue for stockpiles for some time. And there will be no savings on integrating the ‘new territories.’ Other spending items will be cut.”

If revenues fall and the government chooses to expand the deficit by keeping spending levels close to constant,this would add to inflationary pressure and prevent the Central Bank from lowering its key rate.

What happens when the National Wealth Fund runs out

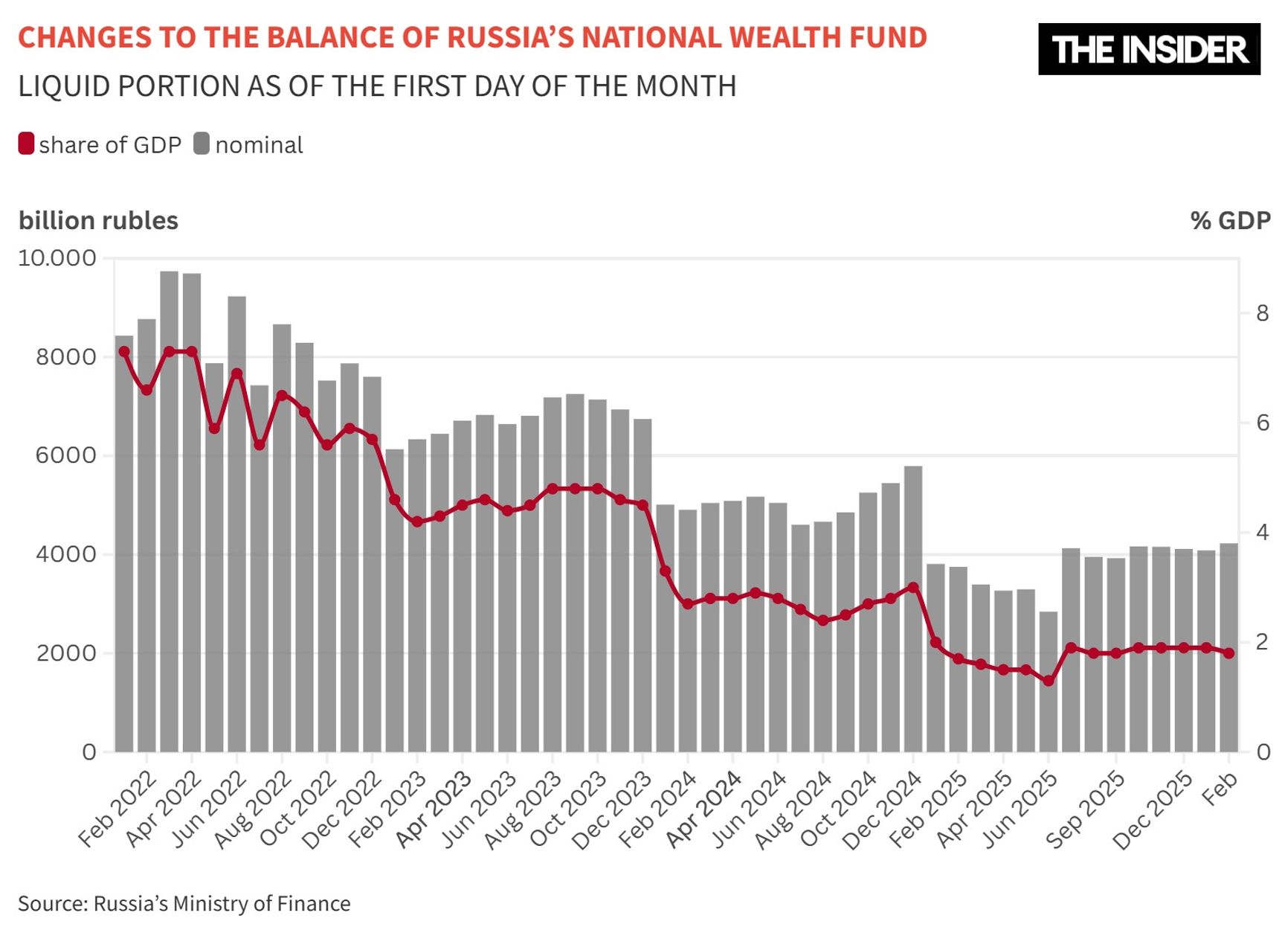

When oil prices fall significantly below budget assumptions, the government covers the shortfall using the National Wealth Fund (NWF), as required by law. That process has already begun. The Finance Ministry said January oil revenues would be 231 billion rubles below the plan and began selling yuan and gold from the fund at a record pace of 12.8 billion rubles a day, faster than during the pandemic.

At that rate, little would remain of the fund’s liquid assets, currently about 4 trillion rubles, by the end of this year. That would leave the government with few options to cover the 2027 deficit. Domestic borrowing is expensive and, in conditions of low unemployment, risks fueling inflation. A sharp rise in prices could also be triggered by another wave of currency depreciation.

The ruble became one of the surprises of 2025. Its 45% appreciation against the dollar was widely unexpected, placing the currency among the world’s top-performing assets, behind only platinum, silver, palladium, and gold, according to Bloomberg. Analysts describe the ruble as unusually strong, but few are willing to predict when or how that status quo might change. Economists surveyed by the Central Bank expect an average exchange rate of 90 rubles per dollar, while the budget assumes a weaker rate of 92.5 per dollar — still far from the 100 level that was recently considered normal.

“The main risk remains ruble devaluation,” said Sergei Aleksashenko. “If the Central Bank starts cutting rates, importers will rush to buy foreign currency, and the exchange rate could collapse quickly, wiping out the gains made in fighting inflation.”

Since the beginning of 2025, production quotas have increased by 2.7 million barrels per day, of which 80–90% have actually entered the market.

“In principle, weakening the ruble is a major reserve,” said Harvard economist Oleg Itskhoki, adding that the government may seek to adjust the exchange rate to make it more favorable for the budget and exporters (for example, by forcing an increase in imports).

Regional depression

The coming year will be particularly difficult for Russia’s regions, which are expected to be hit harder than the federal center by changes to the tax system. They face outflows of funds, rising prices, businesses leaving due to reduced tax benefits, falling profitability, and job losses. Many regional budgets for 2026 are preparing to implement strict austerity measures, including cuts to education and health care spending.

The divergence in business sentiment between the regions and Moscow is especially notable. “My regional contacts assume the situation will worsen, but people are not expecting a catastrophe,” said economist Andrei Yakovlev, an associate researcher at Harvard University’s Davis Center. “There is belt-tightening, employment is shrinking, and there is a sense that demand will contract. There are differences between companies. Those with large debts are struggling. Firms that pursued cautious policies, for example placing excess funds in deposits instead of taking out loans, may be in relatively good financial shape. But overall, sentiment at the regional level is skeptical. Businesses expect greater pressure from tax authorities and stricter administration after tax increases.”

Since the beginning of 2025, production quotas have increased by 2.7 million barrels per day, of which 80–90% have actually entered the market.

In Moscow, Yakovlev noted, the mood is very different. “There is strong interest in seminars about future prospects, and businesspeople have started attending them actively. For some reason, many in Moscow expect sanctions to be lifted and foreign companies to return. There is hope that once an agreement on Ukraine is reached, the stock market will surge, with prices doubling or tripling. Brokers report inflows of client funds into accounts in anticipation of a rally.”

The gap in perceptions between the capital and the regions may reflect the concentration of financial flows that go to Moscow, including profits linked to the “war economy.”

Worse times ahead

Most experts interviewed by The Insider agree that the main problem for the Russian economy is not the risk of a sudden collapse, which few expect this year, but the absence of any sources of growth. The broad consensus is that conditions will gradually deteriorate.

“We have entered a period of stagnation, quiet decay, with neither growth nor decline, everything hovering around zero. Slowly and quietly, we are becoming poorer,” Enikolopov said. “Of course, it matters whether any peace agreement is reached soon. But this will not bring significant relief to the economy — it will only reduce uncertainty somewhat. I do not expect a breakthrough or improved relations with other countries. This will be a Cold War environment.”

Without a change in political leadership, Yakovlev said, Russia is likely to face a prolonged Cold War lasting decades, as Western elites now view Putin’s Russia as a military adversary. With the current political regime in place, a major influx of Western investment in the foreseeable future is highly unlikely. Investor confidence has also been undermined by nationalizations, while China has largely limited its role to trade and has shown little interest in investing in Russian assets.

Since the beginning of 2025, production quotas have increased by 2.7 million barrels per day, of which 80–90% have actually entered the market.

With the current political regime in place, a major influx of Western investment in the foreseeable future is highly unlikely.

“In this state, the economy can function for a very long time,” said economist Itskhoki. “But it will constantly require additional measures to cover spending, gradually cutting funding for various items and increasing fees and taxes. Everyone will adapt. It is not a good situation, but it can last for decades.”

Since the beginning of 2025, production quotas have increased by 2.7 million barrels per day, of which 80–90% have actually entered the market.