From furniture makers to heavy vehicle manufacturer KAMAZ, hundreds of civilian companies are involved in feeding Russia’s military machine. While some non-military sectors are sliding into recession, factories tied to state defense contracts are at least able to maintain stagnation. Of course, the war is draining massive amounts of resources from the economy, and a return to real growth should not be expected until the fighting ends. However, four years of dependence on state contracts have made many companies so reliant on the status quo that, if a truce were to come, Russia would face a painful “withdrawal syndrome” — one in which the civilian sector would slow down even more for a time, and those regions most actively engaged in the defense industry would plunge into deep crisis.

Content

Military dependence

What happens in case of a truce

The possibility of reaching a truce in Ukraine sparks much debate — and skepticism — among political analysts, but economists have reached a consensus: financially, it is not in Russia’s interest to continue the war. The ongoing invasion of Ukraine is devouring reserves, inflating the budget deficit, and driving the economy into recession. Yet few are discussing what would actually happen if the fighting were indeed to miraculously stop. The Russian economy, already restructured onto a war footing, is now completely unprepared for peace.

Military dependence

How much Russia spends on the war is more or less clear: the costs of the federal budget, regional budgets, and businesses forced to act as sponsors are estimated at between 25 billion rubles a day (according to The Insider’s calculations) and 47 billion rubles a day (according to Janis Kluge, a researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs).

By the end of 2025, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) expects Russian military spending to reach 7.2% of GDP — the highest level since Soviet times (in 1990, these outlays came in at 12–13% of GDP). This state-decreed stimulus is distributed among the approximately 6,000 suppliers and contractors making up the Russian military-industrial complex — as outlined in the closed registry of the Ministry of Industry and Trade. The Dossier Center, conveniently, gained access to this data set in spring 2025. It reported that around a third of the lucky enterprises (2,023 to be exact) are involved in the sphere of radio electronics, with other sizable shares in aviation (390 companies), machine tool and heavy engineering (216), the conventional arms industry (167), and the manufacturing of ammunition and special chemicals (86).

However, the military machine is also serviced by civilian-sector enterprises: light industry involved in producing military uniforms, food products, and timber (298 companies), along with those engaged in shipbuilding (265). In short, the registry includes far more than just those companies that produce exclusively military goods. “About 850 enterprises that previously had no interaction with the defense sector were brought into this work,” Minister of Industry Anton Alikhanov explained in June 2024.

Many of them are still operating freely: of the 6,088 enterprises (excluding branches), only 47% have come under sanctions. An analysis of a quarter of the companies in the military-industrial complex registry also showed that the volume of imports for both sanctioned and unsanctioned organizations is generally the same. Thus, the lifting of sanctions — when and if it happens — will not provide many of them with much of an economic boost.

In Russia, more than 6,000 enterprises are tied to state defense contracts, with 850 of them having had no prior dealings with the defense sector before the war

It cannot be said that any regions depend exclusively on defense enterprises. Still, the largest clusters stand out, and if defense contracts were to shrink, this would trigger localized downturns. The largest number of companies from the registry are located in Moscow (1,645), St. Petersburg (786), and the Moscow region (524) — but many legal entities are formally registered in these areas while operating elsewhere. Areas that would be the most likely to suffer economically absent the war are Tatarstan (255), the Nizhny Novgorod region (247), Sverdlovsk (182), Chelyabinsk (141), Samara (111), Rostov (89), Tula (85), Novosibirsk (77), and the Perm region (76).

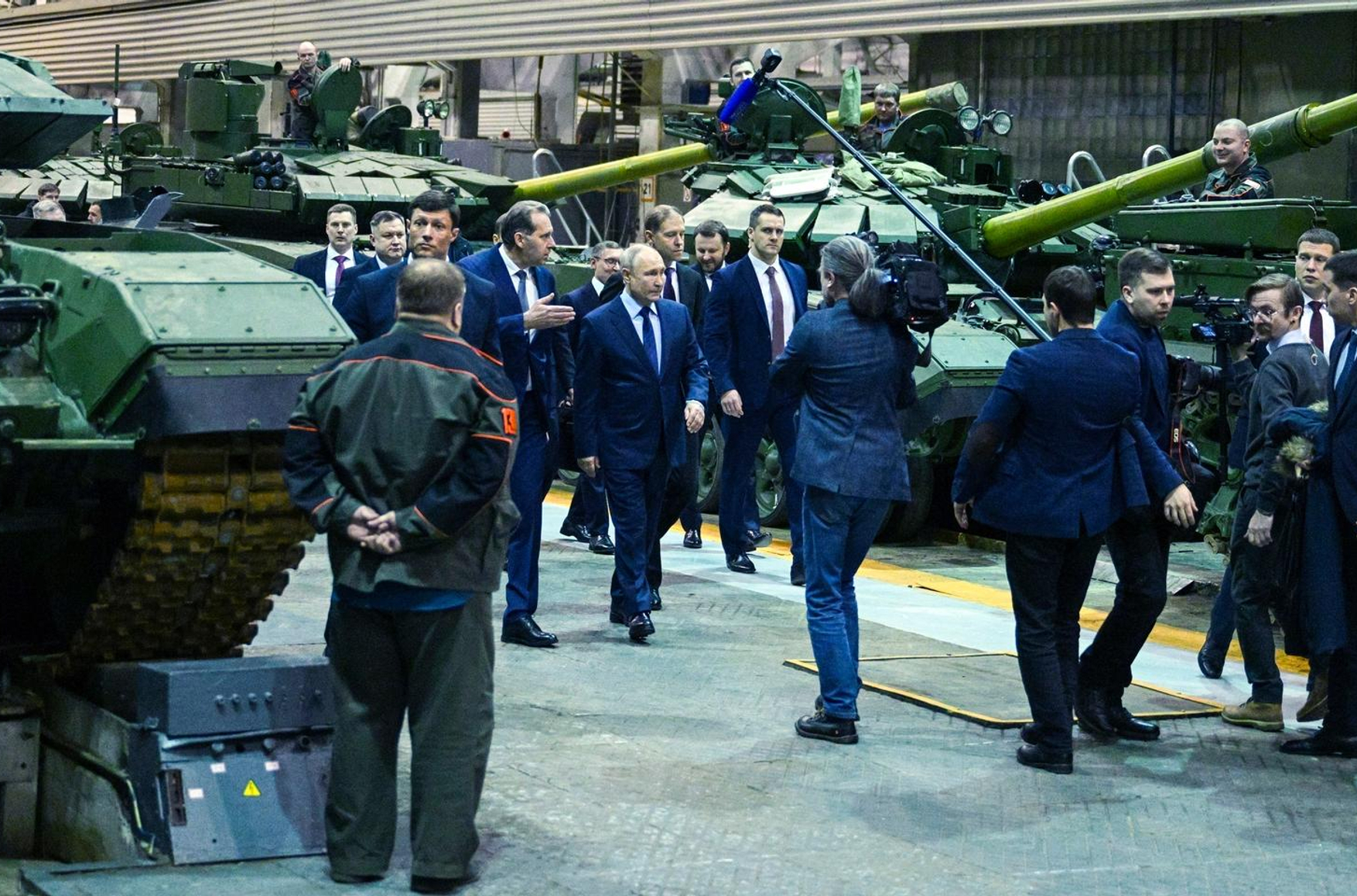

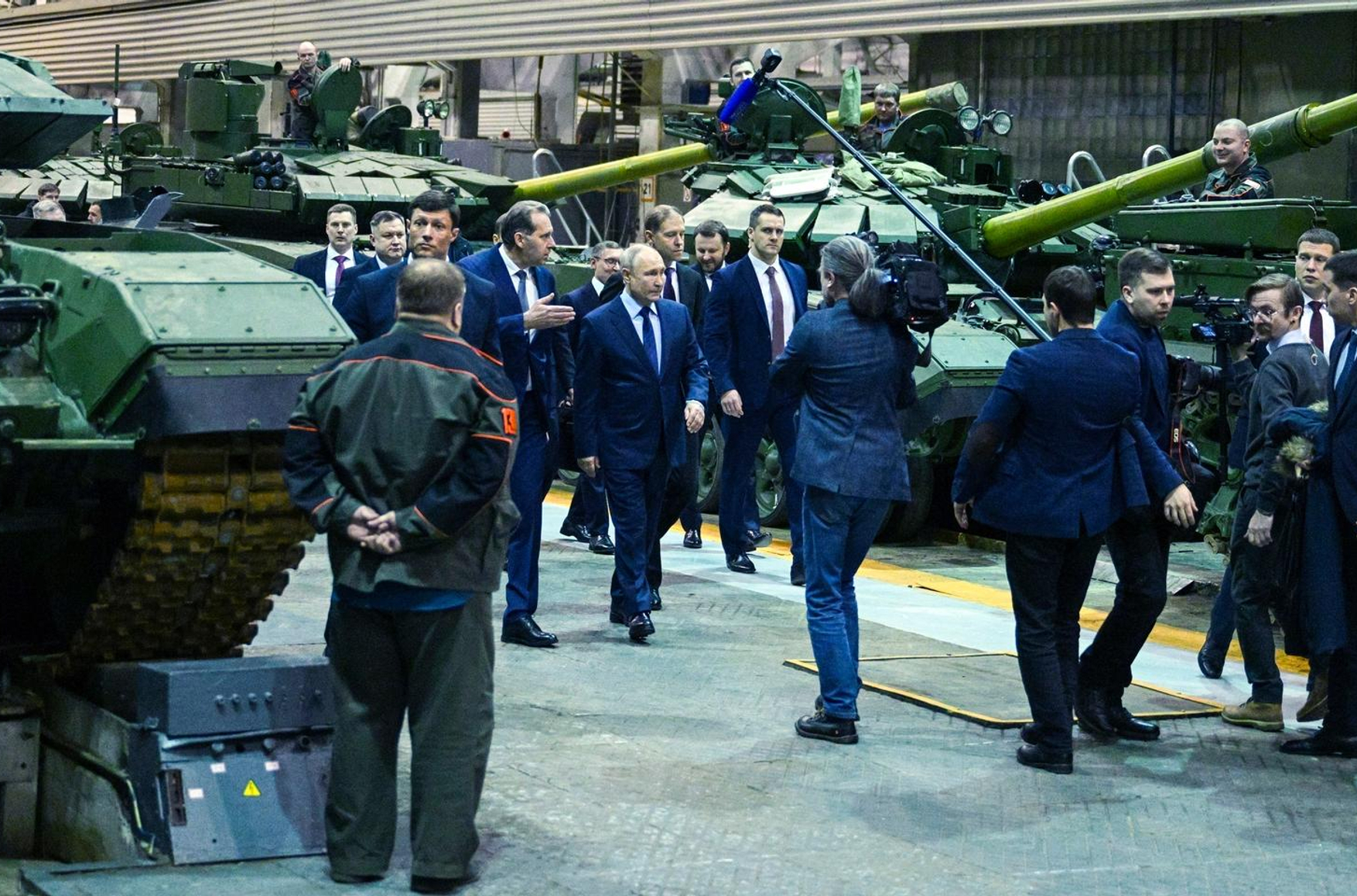

In several areas, defense production makes up a significant share of industry. For example, the Sverdlovsk region specializes in the manufacture of armored vehicles. The region’s largest enterprise, Uralvagonzavod in Nizhny Tagil, produces not only railway rolling stock but also combat hardware: T-14 Armata and modernized T-72B3 tanks, BREM-1M armored recovery vehicles, and BRM-1K combat reconnaissance vehicles among them. Overall, the region accounts for 20% of the country’s defense enterprises.

The Tula region is the largest producer of ammunition, small arms, artillery, and anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons. The defense industry there includes companies such as the Tula Cartridge Works, the Imperial Tula Arms Plant, and NPO Strela, which supplies the Russian army with reconnaissance systems for missile troops and artillery.

Historic military equipment at Uralvagonzavod’s “Armor of Tankograd” festival

The Rostov region, meanwhile, is the birthplace of combat helicopters such as the Mi-24P, the Mi-28N “Night Hunter,” the Mi-35M fire support helicopter, and the Mi-26, capable of transporting up to 20 tons of cargo either in its cabin or on an external sling. Tatarstan, site of the drone factory in Yelabuga, is also home to KAMAZ, which supplies the defense sector with vehicles that account for 30% of the automaker’s total output.

“The Mustang family of trucks are among the most common vehicles in our army… As part of the assignment, models with payload capacities of 4, 6, and 10 tons were developed for transporting personnel, various cargo, and towing trailers weighing from 6 to 12 tons. These vehicles are capable of operating both on roads and off-road, and can cross mountain passes at altitudes of up to 4,600 meters,” a statement on state defense conglomerate Rostec’s website claims.

KAMAZ-5350 from the Mustang-M line with a 6×6 wheel arrangement and a 6-ton payload capacity

A total of 3.8 million people work in the military-industrial complex, according to the Ministry of Industry and Trade. And even this is not enough to keep up with all of the orders. First Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov says that despite a significant flow of workers from civilian plants into the military-industrial complex, the sector still needs about 160,000 more people.

What happens in case of a truce

The fact that war is always harmful to the economy has long ceased to be disputed among economists. An analysis of data from 133 countries for the years 1960–2012 showed that a 1% increase in military spending as a share of GDP reduces economic growth by 1.1 percentage points. As defense spending rises, spending on the social sphere inevitably declines, and in the event of war, the decline in GDP per capita can reach 40–70%, according to experts from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

When looking to past examples, the pace of postwar recovery varies greatly: in about one-third of cases, GDP per capita returns to the level observed in comparable countries without wars within five years; however, in nearly half of cases, it remains below that level even 25 years after the conflict. “Recovery is especially difficult if the peace achieved is unstable. Moreover, even if GDP rebounds, indelible scars may remain, affecting labor resources and capital,” the researchers warn. Wars lead to increased budget spending for decades to come, including financial obligations to veterans and servicing debts accumulated to cover military expenses.

After the end of a war, defense orders do not always fall immediately — sometimes states even increase them to replenish stockpiles of weapons and prevent the sudden collapse of an economy that has become dependent on defense spending. This was the case, for example, after the border conflict between India and Pakistan in 1999, known as the Kargil War: defense spending in both countries began to grow, SIPRI notes, even though, aside from that conflict, the 1990s and 2000s saw only a handful of one-day flare-ups between them.

Russia, in the event of a truce, is also unlikely to reduce defense spending, according to Vladislav Inozemtsev, co-founder of the European Center for Analysis and Strategy: “So much equipment has been lost that for at least another five to ten years, the defense industry will operate at full capacity, or even expand.”

Of course, at some point after the end of the conflict, the defense budget will begin to shrink. Konstantin Sonin, a professor at the University of Chicago, believes that if the war stops, all the factories that have expanded during the conflict — primarily arms producers — will become centers of unemployment: “The ones hit hardest will be the so-called ‘high-tech enterprises’ producing drones, precision missile control systems, and so on. The drama of the late 1980s and 1990s will repeat itself, when hundreds of thousands of people lost their jobs in the defense sector and demanded that the government maintain spending on this pointless production that the country did not need.” At the same time, Sonin clarifies, the demilitarization of Russia’s economy will be necessary in order to maximize the prospects for future growth.

Many civilian enterprises will also lose the support of state defense contracts, and the flow of workers from these companies, as well as from a slowing defense industry, will at the very least cause wage growth to stagnate while annual consumer inflation “eats away” at real incomes. Much will depend on which sanctions are lifted in the event of a truce.

Sonin notes that a complete lifting of sanctions should not be expected even in the event of a peace deal in Ukraine, However, even a partial easing of Russia’s international isolation would have a positive effect on the country’s economy: “Exporters will have more money, Russians in general will have more money, and this will contribute to growth.”

Inozemtsev, for his part, expects such growth to be modest “Massive oil supplies to China and partly to India are contracted a year or two in advance, and Putin will not redirect them to Europe. At most, a return to the European market will mean the restoration of gas supply volumes, but the revenue from them is about five times lower than from oil. As for oil, only the Indian discounts [Russia’s price cuts to India due to reduced supplies to Europe and sanctions] may disappear, and costs for transportation and payment processing fees may shrink, which in total would raise the price by $10–12 per barrel.”

Still, the psychological effect of shifting business sentiment in Russia could at least have some positive impact. “Business leaders are waiting for the war to end to gain certainty about investment decisions. And if peace is established, the economy will begin to recover regardless of oil exports to Europe. The very direction of such exports is of little importance now,” Inozemtsev concluded.