Orhan Qereman / Reuters

Orhan Qereman / Reuters

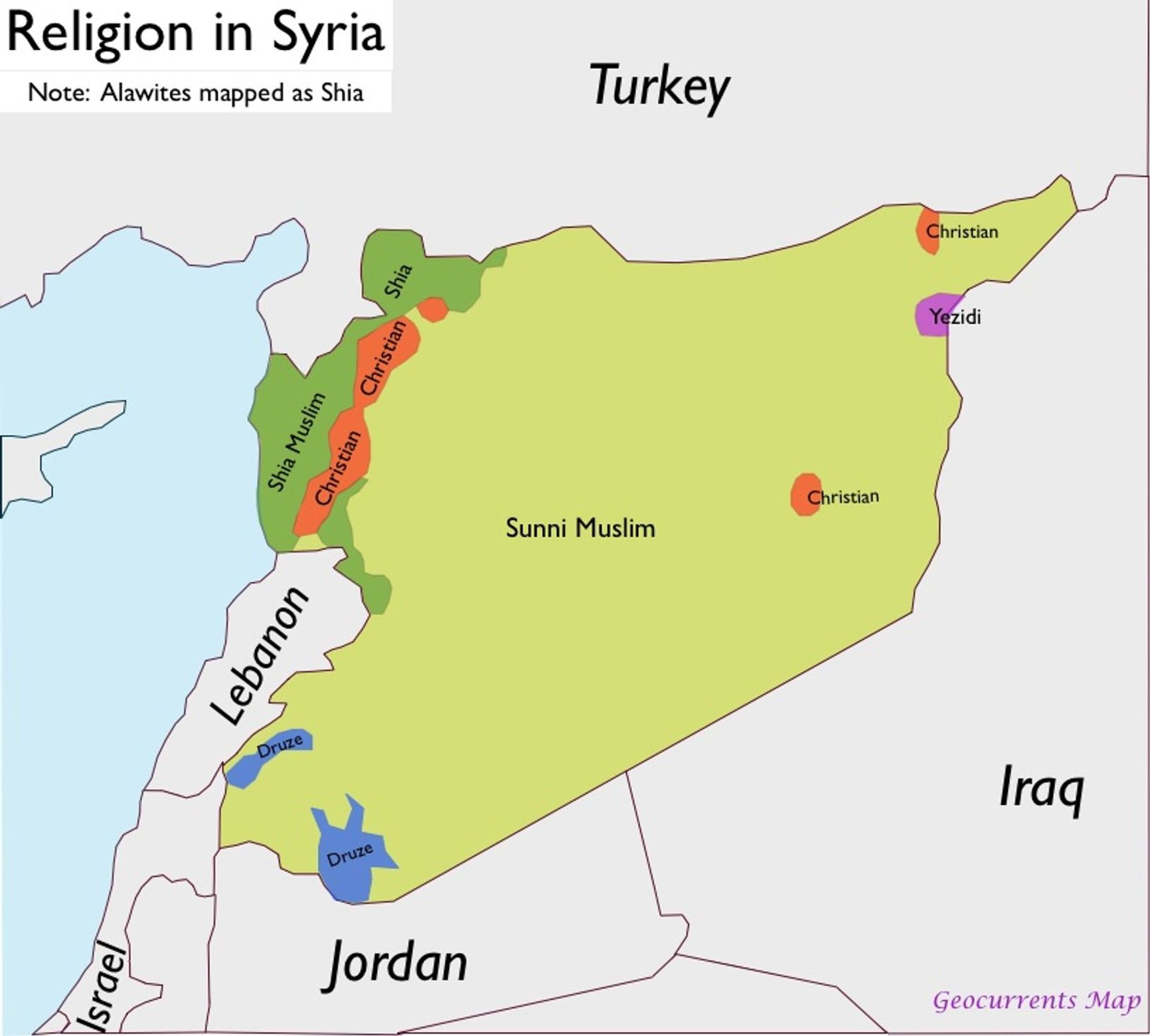

Donald Trump announced his intention to lift U.S. sanctions on Syria that have been in place since the rule of Bashar al-Assad, but he also demanded that the new Syrian authorities guarantee stability in the country. Syria's disparate religious and ethnic composition may hinder this endeavor. At the time the civil war broke out, following the revolution of 2011, Sunni Muslims made up about 70% of the country's population. The remaining 30% came from religious minorities, the most prominent of which were the ruling Alawites, along with Christians, Shiites, and Druze. But the war has persuaded many of these to flee the country. The new Syrian authorities, who until recently were representatives of radical Sunni groups, tend to view non-Sunnis as accomplices or sympathizers of the former regime — if not as outright enemies. Members of minority denominations are well aware of this attitude.

Historical divide

Assad seeks help from Christians

Sunni vs. Shia

The Druze of Israel

“Christians to Beirut, Shiites to hell,” al-Qaeda and associated groups wrote on the walls in cities and towns they captured at the outset of the Syrian civil war a little over a decade ago. In doing so, the Islamists emphasized the religious nature of the confrontation. Unwittingly, they also played into the hands of Assad's propaganda, which portrayed the war as a sectarian conflict pitting the country’s Christians, Druze, Shiites, Alawites, and secular Sunnis on one side, and jihadists and terrorists seeking to expel or destroy all infidels and build an Islamist theocracy on the other.

Both sides simplified the nature of the conflict. It was easier for al-Qaeda to recruit Sunni Muslims by convincing them that all their troubles were caused by foreigners. Meanwhile, Druze and Christians were likely more willing to join Assad’s army if they felt intimidated by an internal enemy.

Everyone was accustomed to viewing the country as being divided along sectarian lines. It is well known in Syria that Latakia and Tartus are predominantly Alawite cities, that the far south is a Druze stronghold, that Shiite communities are located south of Damascus, and that the capital itself contains distinct neighborhoods for Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and members of the Armenian Church.

For centuries, people of the same faiths preferred to settle together, usually near a church, mosque, or other shrine, living in their village or neighborhood according to their own rules, without fear of offending their neighbors of different beliefs, and resolving matters through their own judges and officials. This division was encouraged by the authorities of the Ottoman Empire, which ruled Syria for centuries. Under the Ottomans, a system known as the millet granted Christian and Jewish communities significant autonomy in their internal affairs and ensured non-interference from imperial Muslim authorities.

The millet made governance of the vast empire more flexible and allowed the sultans' non-Muslim subjects to retain their customs and traditions. The downside of this system was the strengthening of a parochial consciousness among the people of Syria. Christian Syrian thinker and opposition figure Michel Kilo (1940-2021) wrote that Syria had no civil society in Ottoman times, that Syrians felt no unity with anyone other than their co-religionists, and that the boundaries of neighborhoods were akin to state borders — beyond which strangers lived. The moment the empire's grasp weakened, these interfaith boundaries began to bleed.

Perhaps the most violent outbreak of sectarian violence took place in the middle of the 19th century. Economic and political intervention in the Middle East by European powers led to significant enrichment and a sharp rise in the social status of Syrian Christians, with whom Paris and London preferred to conduct business, bypassing Ottoman officials and local Muslim authorities. Left without a steady income due to European machinations, the Muslims of Damascus soon grew discontented, and the failure of central authorities to quickly restore order to the imperial periphery led to several days of pogroms, during which at least 2,500 people were killed.

The massacre triggered one of the largest waves of Christian emigration from Syria in modern history. Fearing a repeat of the pogroms, thousands of people fled their homes to seek refuge in other countries, sometimes moving as far away as Brazil. The Syrian diaspora in South America has been mostly Christian ever since.

A theological and legal term commonly used in Muslim countries — a religious community with autonomous administrative institutions in the fields of judiciary, education, healthcare, etc., usually located in specially designated areas or city quarters. From the 15th to the 20th century, the concept of millet became widely used in the Ottoman Empire to classify the empire’s populations according to their religious affiliation.

Even today, the Syrian diaspora in South America is mostly Christian

When the forces of the first righteous Caliph, Abu Bakr, reached Syrian territory in the 7th century, the vast majority of the local population was Christian. Damascus, said to have received the faith directly from the apostle Peter, had more followers of Christ than any other city in the world. It was in Syria that the religious phenomenon known as pillar-making — the voluntary withdrawal from the world and seclusion in prayer on a remote hilltop — originated. One of the main centers of Christianity — the city of Antioch — was also located in Syria. Today, it lies on the border with Turkey’s Hatay province.

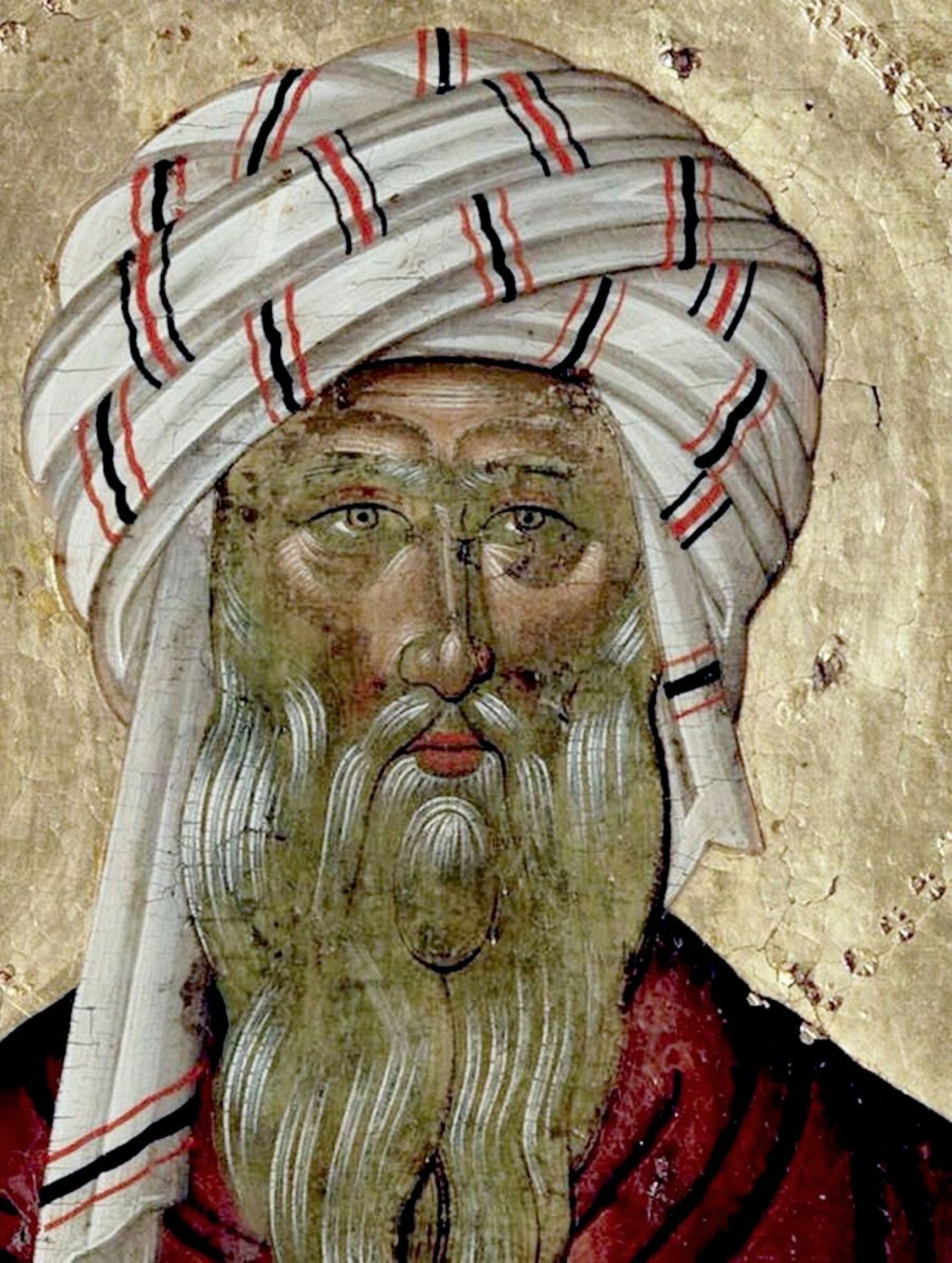

When Islam emerged, Syria was a province of the Byzantine Empire, but its proximity to Persia, the perennial enemy of Eastern Rome, left it vulnerable to outside attack. Exhausted by endless wars with the Persians, Byzantium was unable to protect its eastern reaches from conquest by the Arabs. Some cities were ceded to the Muslims without a fight. Mansur, a Damascus official, negotiated with the conquerors and opened the city gates to them in exchange for employment at the caliphs' court for himself, his son, and even his grandson.

Mansur's grandson ultimately gave up his high court post to become a monk. The world knows him as the theologian John Damascene. John, who lived side by side with Muslims all his life, never recognized Islam as an independent religion. For him, it remained an odd heresy, a twisted and corrupted interpretation of the Bible, in which Jesus was reduced to the role of just one of God's prophets.

A theological and legal term commonly used in Muslim countries — a religious community with autonomous administrative institutions in the fields of judiciary, education, healthcare, etc., usually located in specially designated areas or city quarters. From the 15th to the 20th century, the concept of millet became widely used in the Ottoman Empire to classify the empire’s populations according to their religious affiliation.

In the Islamic world, the story of John Damascene — a Christian who held a prominent position in the caliphate, and openly criticized Islam, and was permitted to leave government service without repercussions — symbolizes the openness and tolerance of the Islamic powers of old.

Perhaps some members of the Umayyad dynasty, which settled in Syria and made Damascus their capital, truly held a fondness for Christians. But Damascene and his co-religionists most likely escaped persecution and forced conversion to Islam for economic reasons. Christians and Jews living under Muslim rulers were required to pay a special additional tax called jizya.

A theological and legal term commonly used in Muslim countries — a religious community with autonomous administrative institutions in the fields of judiciary, education, healthcare, etc., usually located in specially designated areas or city quarters. From the 15th to the 20th century, the concept of millet became widely used in the Ottoman Empire to classify the empire’s populations according to their religious affiliation.

John Damascene and his co-religionists most likely escaped persecution and forced conversion to Islam for economic reasons

In addition, Christian merchants were required to pay a duty to the Muslim authorities of the cities where they traded — usually around 10% of the value of the goods. Converts to Islam ceased paying jizya and other duties, thereby reducing the revenue flowing to the treasury. So the Umayyads, and those who ruled Syria after them, were not overly zealous in converting Christians to their faith.

By contrast, those who chose to convert to Islam received undeniable advantages. In addition to saving money on jizya payments, Muslims could pursue a career in the army or city administration. Muslims were free to choose their place of residence, whereas Christians, as researcher Milka Levy-Rubin notes in her book Non-Muslims in the Early Islamic Empire: From Surrender to Coexistence, were tied to their birthplace and could not stay more than three days in other cities. Overall, being a Muslim was easier, safer, and more advantageous, factors that contributed to the gradual conversion of much of Syria’s Christian population to Islam. The Islamization of Syrians stretched on for centuries, never reaching completion.

When the Syrian civil war began in 2011, Christians still made up around 10% of Syria's population.

Despite their official rhetoric, under both Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar, Syrian Christians were not actually favored by the authorities. For the most part, official support was limited to repairing churches and appointing representatives of Christian communities to mid- and lower-level positions in the government and military. After the outbreak of war, a significant portion of state propaganda was aimed specifically at Christians, many of whom had taken part in anti-government demonstrations or even joined the rebels.

Propaganda framed anti-government demonstrations as anti-Christian, portraying Bashar al-Assad as the sole protector of Christians — with posters in Christian neighborhoods often depicting him alongside a crucifix or the Virgin Mary. The president began visiting churches and appearing in photographs with priests and parishioners, and in 2017 he appointed a Christian, Hammouda Sabbagh, as speaker of parliament.

A theological and legal term commonly used in Muslim countries — a religious community with autonomous administrative institutions in the fields of judiciary, education, healthcare, etc., usually located in specially designated areas or city quarters. From the 15th to the 20th century, the concept of millet became widely used in the Ottoman Empire to classify the empire’s populations according to their religious affiliation.

Propaganda posters in Christian neighborhoods often depicted Assad alongside a crucifix or the Virgin Mary

State propagandists adopted a multi-pronged approach. Prominent clergy held prayer services for Assad’s health. Some churches displayed his portraits. Priests openly voiced their support for him.

Of course, there were exceptions. In 2014, for example, a group of Syrian Christian intellectuals published an appeal accusing the Assad regime of torturing and killing people, bombing civilian neighborhoods, and turning the church into a tool of government propaganda. The address described priests who supported Assad as “enemies of Christ, Christianity, and all the sons of the Syrian people.”

However, it is important to acknowledge that most Christians viewed Assad as the lesser evil compared to al-Qaeda and other radical groups. In this respect, Assad's propaganda was extremely successful.

A theological and legal term commonly used in Muslim countries — a religious community with autonomous administrative institutions in the fields of judiciary, education, healthcare, etc., usually located in specially designated areas or city quarters. From the 15th to the 20th century, the concept of millet became widely used in the Ottoman Empire to classify the empire’s populations according to their religious affiliation.

The propaganda disseminated by the fallen regime also affected its opponents’ understanding of allegiances during the war. Former rebels, who form the core of the new government's security services, often perceive Christians as collaborators of the enemy, forcing them to flee the country for fear of persecution.

However, the flight of Christians began much earlier: they have been leaving en masse since the beginning of the civil war. As of 2023, some 450,000 Christians of different denominations remained in Syria, compared to the pre-war number of 2 million. The French Catholic publication La Croix reports (though without citing sources) that by the end of 2024, 85% of Syria's Christians had left the country, and their share of the total population had dropped to 2%.

It is not just Christians who are fleeing Syria. The Shia Muslim community may also cease to exist before the country stabilizes. Even before the war, the Shia made up only about 3% of Syria's population. Radical Sunni Muslims — who have come to power in Syria —view Shiites as heretics and apostates. At the heart of Shiite doctrine lies the belief that the descendants of the Prophet Muhammad possess hidden divine knowledge and a perception of reality inaccessible to the rest of humanity. The Shia refer to the bearers of this divine spark as Imams, and the largest branch of Shiism, the Twelvers, is united around the belief that there were twelve such Imams, the last of whom, during the Middle Ages, entered a mystical state of occultation and could return to the world at any moment.

In Syria, followers of Twelver Shiism were fewer in number than those of another Shiite branch — the Ismailis, who share the core principles of the Shiite worldview. They believe that at any given time two Imams exist simultaneously — one visible, embodied in a direct descendant of Muhammad, and one hidden, possessing an unknowable nature. For Sunnis, all such beliefs about Imams are considered grave heresy — an attempt to attribute divine qualities to human beings (even if they are descendants of the Prophet).

A theological and legal term commonly used in Muslim countries — a religious community with autonomous administrative institutions in the fields of judiciary, education, healthcare, etc., usually located in specially designated areas or city quarters. From the 15th to the 20th century, the concept of millet became widely used in the Ottoman Empire to classify the empire’s populations according to their religious affiliation.

For Sunnis, all such beliefs about Imams are considered grave heresy — an attempt to attribute divine qualities to human beings

Notably, Twelver Shiites were among the key pillars of the Assad regime, which enjoyed the direct military and financial support of Shiite Iran in the civil war. With Iranian help, thousands of Shiite volunteers from various countries arrived in Syria. Assad’s opponents claimed that the foreigners arrived with their families, settling in homes in Damascus or its immediate suburbs — a practice they referred to as the ‘Shiification’ of Syria.

In their view, Shiism is a foreign doctrine imposed by Iran, which has indeed done much to promote Shiism. But Shiites existed in Syria long before the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1979. Most likely, Shiite communities appeared in the country around the same time as the final split of Islam into Sunni and Shiite branches — that is, way back in the Middle Ages.

Suburban Damascus is home to one of the main Shiite shrines — the tomb of Zainab, granddaughter of the Prophet Muhammad and daughter of the first Imam, Ali. The shrine has been a Shiite pilgrimage site since at least the 14th century. Almost all residents living around the shrine are Twelver Shiites — or at least, that was the case under Assad.

A theological and legal term commonly used in Muslim countries — a religious community with autonomous administrative institutions in the fields of judiciary, education, healthcare, etc., usually located in specially designated areas or city quarters. From the 15th to the 20th century, the concept of millet became widely used in the Ottoman Empire to classify the empire’s populations according to their religious affiliation.

The Ismailis also have their own town, Salamiyah, located near Hama. Back in the 1840s, the Ottoman authorities gave these lands to the Ismailis, and since then Salamiyah has been one of the main centers of Ismailism. The group claims that by the time the Ottomans granted them land, their community had been present in Syria for over 1,000 years.

Unlike the Twelvers, the Ismailis were not a prominent force in the Assad army or allied factions. In 2014 the central authorities began withdrawing troops from Salamiyah in the face of advancing ISIS forces after the Ismailis failed to mobilize the 24,000 soldiers demanded by Damascus into Assad’s army.

It seems that Bashar al-Assad tried to use the fate of the Syrian Ismailis as leverage against Aga Khan IV, their spiritual leader and living Imam. A billionaire who maintained friendly relations with European politicians and Middle Eastern monarchs, Aga Khan could have made a significant impact on the course of the war in Syria — which is likely what Assad wanted. Whether or not the Imam made a deal with Damascus remains unknown, but in either case, Salamiyah was never captured by ISIS.

Following Assad's flight, the Ismaili community of Salamiyah reached an agreement with the rebels under which the minority pledged to disarm and neutralize all pro-Assad groups operating in the city. In short, the Ismailis agreed to cooperate with the new government.

They are now trying to insert themselves into the new political reality by assuming the role of mediators between the Sunni authorities and religious minorities. As it turns out, this role also comes with its hazards — since the regime’s fall in late 2024, several attacks on Ismailis by supporters of the fugitive president have been recorded, along with at least two extrajudicial executions of Ismaili militia fighters. It is not surprising, therefore, that Ismailis, like Twelver Shiites, are fleeing the country by the thousands.

About 1,000 years ago, a faction of the Ismailis were persuaded by the sermons of the theologian al-Darazi to split from the community. Al-Darazi taught that the souls of the dead are reincarnated in the bodies of infants, and that the soul of the first man — Adam, imbued with divine essence — traveled through the bodies of the caliphs, manifesting most fully by incarnating in al-Darazi’s contemporary, the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim.

The Caliph tolerated the heretic's sermons for some time (perhaps even trying to benefit from his own deification), but finally ordered al-Darazi's execution. The final formation of the religious doctrine of the new Ismaili sect was completed by a different figure, Hamza ibn Ali. However, the community took its name from the executed al-Darazi. Today, they are still called the Druze.

The Druze distanced themselves from any association with the Ismailis fairly quickly. Even the Prophet Muhammad, in their minds, was far less worthy than al-Hakim. They destroyed mosques, viewing them as centers of misguidance, and believed that at the end of time al-Hakim would destroy all Muslim shrines. Fleeing persecution by the Fatimid authorities, who were outraged by such blasphemy, the community that had originated in Cairo moved to Syria.

Soon it became completely isolated. No one could convert to the Druze faith — one could only be born a Druze. The sacred books of the Druze and their secret knowledge are inaccessible to outsiders, while the Druze themselves, to save their lives, often formally accepted the religion of rulers or neighbors but secretly remained loyal to the deified al-Hakim. “They are born as Druze, live as Christians, and die as Muslims,” it was said of the Druze centuries ago.

A theological and legal term commonly used in Muslim countries — a religious community with autonomous administrative institutions in the fields of judiciary, education, healthcare, etc., usually located in specially designated areas or city quarters. From the 15th to the 20th century, the concept of millet became widely used in the Ottoman Empire to classify the empire’s populations according to their religious affiliation.

Even the Prophet Muhammad was far less worthy than al-Hakim in the eyes of the Druze

The Druze practice mystical rites, such as the ritual of notq, during which the believer enters a trance and recalls past lives. In general, the doctrines and religious traditions of the Druze have diverged so far from their Islamic origins that Mordechai Nisan, author of Minorities in the Middle East, not only classifies the Druze faith as a separate religion but also describes some of its tenets as explicitly anti-Islamic

The Druze live in isolated communities — typically apart from other groups — in Lebanon and Israel, while in Syria, the vast majority reside in the south, near the Israeli border. There are also Druze communities in the Golan Heights, which have been occupied by Israel since the Six-Day War in 1967.

Israeli Druze are subject to conscription and are regarded as some of the most patriotic and committed soldiers in the country. Druze loyalty to the Jewish state has fueled a conspiracy theory about a so-called “Druze-Zionist alliance,” in which Druze and Jews secretly agreed to fight together against Muslims and then control the conquered lands.

A theological and legal term commonly used in Muslim countries — a religious community with autonomous administrative institutions in the fields of judiciary, education, healthcare, etc., usually located in specially designated areas or city quarters. From the 15th to the 20th century, the concept of millet became widely used in the Ottoman Empire to classify the empire’s populations according to their religious affiliation.

All of the above made the Druze enemies of radical Muslims by default. However, it would be a stretch to call them friends of the Assad regime. After the civil war began, the Druze tried to maintain neutrality. This allowed them to receive subsidies from the regime and access to government positions and state-funded jobs without taking up arms or provoking the armed opposition by allying with the hated authorities.

But in 2015, after the massacre of Druze near the city of Idlib by fighters of Jabhat al-Nusra — later rebranded as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, whose military and ideological leaders have since taken control of the state — the Druze openly sided with Assad, believing he could protect their community. Even so, their alliance was short-lived.

Already in the 2020s, Assad was forced to cut funding for local officials and cancel subsidies for several essential goods due to economic hardship. Many Druze perceived this as a betrayal and began to speak out against the authorities.

Still, it was easier for the Druze to find common ground with the Assad government than with radical Islamists. After all, the embattled president belonged to the Alawites, who are quite similar to the Druze. The Alawites are also a closed community, into which one can only be born. Their roots trace back to Ismailism, and their followers similarly engage in mystical practices and believe in the transmigration of souls. It is therefore unsurprising that the Druze greeted the emergence of the new authorities with extreme wariness. Some community leaders have explicitly urged their co-religionists not to trust the Islamists in Damascus and to remain armed until the new authorities provide credible security guarantees for the Druze. A portion of the Druze took this as a call to actively oppose the central government.

Meanwhile, neighboring Israel’s actions — bombing both military and civilian targets in Syria — have further fueled mutual distrust, as Israel justifies these strikes by claiming that they protect the Druze from violence by the new government’s security forces. Unsurprisingly, these bombings have failed to quell the sectarian strife. Likewise, a joint statement from Druze leaders affirming Damascus’s authority and urging their community to abandon armed resistance did little to stabilize the situation.

Syria remains, as it has for centuries, a divided country — where religious affiliation means far more than civic identity. The new authorities promise to change this reality by making Syria equally welcoming for all its inhabitants and ending sectarian strife. However, the longer the instability persists, the faster members of religious minorities will flee, robbing Syria of its unique character.

A theological and legal term commonly used in Muslim countries — a religious community with autonomous administrative institutions in the fields of judiciary, education, healthcare, etc., usually located in specially designated areas or city quarters. From the 15th to the 20th century, the concept of millet became widely used in the Ottoman Empire to classify the empire’s populations according to their religious affiliation.

К сожалению, браузер, которым вы пользуйтесь, устарел и не позволяет корректно отображать сайт. Пожалуйста, установите любой из современных браузеров, например:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari