For the first time in 50 years, Syrians celebrated the New Year without the Assad regime. A month after the overthrow of one of the Middle East's most authoritarian governments, much of the country appears to have returned to normalcy. Immigrants have started returning to Syria, but the situation remains far from stable. In the north, clashes continue between pro-Turkish groups and Kurdish forces, while the new leadership from Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) battles against Assad loyalists who refuse to surrender. Religious and ethnic minorities, including Christians, Armenians, and Alawites, are expressing concerns about potential discrimination under the new regime. The Insider interviewed Syrians about their feelings and expectations.

Content

“We sang throughout the flight”

New country, new opportunities

“They shouted for women to wear hijabs”

“We are Alawites. We fear for our children's future”

Changing attitudes toward Russians in Syria

Idlib: A glimpse of Syria’s future

“We sang throughout the flight”

Damascus International Airport reopened on Jan. 7, 2025, welcoming its first international commercial flight from Doha, operated by Qatar Airways. Despite the captain’s requests for passengers to remain seated and fasten their seatbelts, the cabin erupted in celebration upon their arrival in the new Syria. Passengers stood up, waved the new flag with three red stars, danced, and sang in unison. For many, this marked their first opportunity to reunite with loved ones after more than 12 years of bloody conflict.

The celebrations continued inside the airport, which had been closed for a month following the fall of the old regime. Under Assad, the airport remained in operation, but only received a handful of airlines, as most international carriers canceled flights after the civil war began in 2011.

As one returning Syrian told reporters: “It’s an incredible feeling. My soul has been in Damascus since the day of its liberation , and now I’ve arrived here on the first commercial flight from Qatar. Syria is ours!”

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

Syrians at Damascus Airport greet relatives returning from abroad on the first commercial flight, Jan. 7, 2025.

Photo: wingsmagazine.com

“We sang throughout the flight, celebrating like we were at a wedding,” Syrian dissident Bassem al-Hariri, who left Assad’s police force and fled the country in 2012, described the flight home.

According to a UNHCR report released on Jan. 4, 2025, over 115,000 Syrians have returned from Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, and elsewhere since the overthrow of Assad.

Mass internal migration is also underway inside Syria itself. Families torn apart by the war are now attempting to rebuild their lives.

“The whole country is living out of suitcases right now. Everyone’s either traveling or figuring out where to go. Housing is scarce — everything seized by the regime during their last military campaign has been destroyed,” said Natalia, a doctor in the northwestern Idlib province. Natalia, who moved to Syria in 2015, has been working in the opposition-controlled area since 2017. She described the current atmosphere in Syria as “joy mixed with tears.”

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

Everything seized by the Assad regime during its last military campaign has been destroyed.

“Today, we were crying at my hospital because my assistant has to move, but she doesn’t want to leave her job,” Natalia explained. “It’s impossible to maintain two homes — one in Damascus and one here in Idlib, which are over 300 kilometers apart. Here, she has a job, earning $250 a month, which is enough to survive. It’s all so joyful, yet so sad and difficult at the same time.”

On Dec. 8, power in Syria was transferred to the armed opposition, led by two main factions: Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and the pro-Turkish Syrian National Army. The latter limited its control to the northern territories, where its clashes with Kurdish groups continue to this day.

The opposition declared a policy of “Syria for all Syrians,” promising to uphold the rights of women and minorities and avoid persecuting employees of state media outlets who took part in Assad-era propaganda. However, it later announced plans to bring these individuals to trial, though the nature of the proposed proceedings remains unclear.

New country, new opportunities

For many, the change of power in Syria has become an opportunity to start a new life. Kursk native Olivia, along with her Syrian husband, Bashar, were among the first to arrive in the country after the regime fell, moving to Latakia from Turkey. “We packed whatever we had into boxes and bags and set off,” Olivia said.

Olivia had never been to Syria before. She married Bashar in August after years of communicating online: “I always asked my husband why he wouldn’t return to his homeland and live there. He said that if he went back, Assad’s army would conscript him, and he didn’t want to fight against his own people.”

The couple is now preparing to open a small burger joint in Latakia. However, according to Olivia, the process has been overshadowed by hostility from pro-Assad Russians living in Syria, as the political divisions in Syrian society have also extended to the Russian diaspora.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

The political divisions in Syrian society have also extended to the Russian diaspora.

“I posted an ad for our ‘Mini-House’ [cafe], and a woman with Assad’s flag on her profile picture commented that we were supposedly harboring terrorists,” Olivia said. “I offered to treat her to coffee, but she replied, ‘I don’t need your coffee. Give us back our flag!’”

“I wanted to meet women who are also married to Syrians, but it was very hard to find common ground because many of them are Assad supporters, and I’m the opposite. I stayed in their group for three days and was heavily bullied. They said no one needs our burgers and claimed we were kicked out of Turkey, which isn’t true. There was a lot of negativity,” Olivia explained. Before Assad’s fall, the couple did live and work in Turkey, but they were not expelled. Returning to Syria was a voluntary decision, as Bashar had long wanted to go back. “My husband’s parents have a house here, so we’ve essentially returned home,” she added.

The province of Latakia, where the family now lives, has felt the impact of Israeli airstrikes. Witnesses described the Dec. 16 attack as the most intense in a decade. Syrians hope the situation does not escalate into another war.

“These [Israeli strikes] are meant to destroy missiles and chemical weapons as a way for Israel to ensure its own safety. But was life in Kursk any better? Is it better now when rockets and drones are flying overhead?” Olivia reflected.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

The port of Latakia after Israeli strikes on the night of Dec. 16, 2024.

Photo: YNet

Many Syrians are outraged by how Bashar al-Assad left the country. “So many people lost their homes and have no support. The most despicable thing Assad could do was flee with large sums of money that were essentially Syria’s reserves,” Olivia continued.

The opposition forces that came to power are now referred to by Syrians as “our army.” Olivia, Bashar, and others interviewed by The Insider believe that Russians in Syria are not in danger. They say that any claims about Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) posing a threat to them are mostly spread by supporters of Assad, Iran, or the Russian media.

“Our army wants Russia to reconsider its stance and stop viewing them as a terrorist organization,” Olivia notes. “There’s a lot of harassment toward those who support the new authorities. Naturally, people who previously supported Assad or worked with his structures are leaving immediately because they’re afraid of reprisals. But no, our army has no such goal.”

Olivia and Bashar allowed their names to be published — unlike Russian women who supported the old regime. “There’s nothing to fear anymore. If we used to be scared, now we breathe freely,” they said.

Many Syrians who fled the country remain hesitant to return. The nation is still in the grip of a severe economic crisis, just as it was under Assad. Western countries have promised to lift sanctions only after the new government clarifies its policies, particularly those regarding human rights.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

Western countries have promised to lift sanctions only after the new government clarifies its policies, particularly those regarding human rights.

“They shouted for women to wear hijabs”

Syrian women’s rights activists have called on the new government to include women in forming the administration. The Syrian Women’s Political Movement (SWPM) has been particularly vocal. Meanwhile, secular Syrian women fear they may be forced to wear hijabs.

“In Aleppo, soldiers drove around in pickup trucks shouting through loudspeakers for women to wear hijabs,” one resident told The Insider. “Sometimes they approach couples on the street and ask them not to hold hands if they’re not married.”

The new authorities have not announced plans to make Syria a Sharia state, but some of their actions have raised concerns among secular Syrians. For example, the Facebook page of the transitional government’s Ministry of Education published a proposed curriculum with an Islamic slant. Terms like “defending the nation” were replaced with “defending Allah,” with other potential changes including Evolution and the Big Bang theory being dropped from science teaching. The transitional government quickly clarified that the publication was only a recommendation and that the curriculum would be revised only after the formation of specialized committees.

Meanwhile, patriotic activities widely promoted under Assad have already been discontinued in schools.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

A patriotic lesson in Homs pictured in 2017. Schoolchildren stage a performance titled “Arresting Terrorists,” with students also playing the roles of the terrorists.

A Damascus resident told The Insider how armed men in military uniforms disrupted a café where a group of young men and women were celebrating a birthday. “They didn’t like that the women weren’t wearing hijabs and were sitting together with men despite not being married,” she said. However, she could not confirm whether or not the men were representatives of the new regime.

Several sources told The Insider that talk of potential Islamization began to surface in January. In addition to her burger cafe, Olivia from Kursk is planning to open an online hijab store, as 80% of the population are Sunni Muslims. Representatives of Christian and Armenian communities interviewed by The Insider hope that the new government will prioritize secular law over Islamic law.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

A photo with a blurred image of German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock during a meeting with Syria's new authorities sparked active discussions in Syrian society.

Photo: Almharar Agency

So far, the new authorities have made no official attempts to impose Sharia-style living. For the first time in 50 years, New Year celebrations took place in Damascus without the Assad regime. Western pop music played on the city’s main square on New Year’s Eve, and Christmas celebrations for Christians occurred without incident.

Key tensions are already beginning to take shape, significantly impacting the future of the country. These include conflicts between pro-Turkish and Kurdish factions, disputes between proponents of Sharia and secular lifestyles, and societal attitudes toward Alawites — the branch of Islam to which the Assad family belongs and a community that largely supported the former regime.

“We are Alawites. We fear for our children's future”

Not all Syrians are returning home; some fear retaliation from Assad loyalists.

Hussam Kassas, a former paramedic and activist now living in the UK, documented human rights violations and war crimes by all sides during the civil war in his hometown of Darayya, near Damascus. He shared this information with journalists. Kassas told CNN that he dreams of returning but does not want to endanger his family.

“I do not want my family, my sons, to become the victims of a revenge killing,” Kassas said. “Just because the Syrian president fled the country, that doesn’t mean his soldiers and secret service officers suddenly become peaceful angels.”

Ahmad al-Sharaa, the leader of the new Syrian government, has claimed that it is working to eliminate threats from armed groups that still support Assad.

“Everyone was given time to surrender. In every major city, we’ve opened reconciliation centers where people can come with their rusty Kalashnikovs, hand them over, and say, ‘That’s it, I’m done. I’m going home to plant potatoes. I won’t do this anymore, I’m sorry,’” said Natalia. “They’ll be let go and can live peacefully.”

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

Former soldiers of the Assad regime's army queue for registration at one of the reconciliation points in Latakia.

Photo: Leo Correa / AP Photo

However, many Alawites fear that “eliminating threats” could lead to widespread persecution of their community. Syria is home to 2.5 million Alawites, and they made up two-thirds of Assad’s officer corps. Videos circulating on social media show security forces raiding the homes of former regime supporters.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

However, many Alawites fear that “eliminating threats” from armed groups that still support Assad could lead to widespread persecution of their community.

“Just last night, armed men entered the house of a local resident. They drive into villages in pickups, knowing exactly which houses to target. They break in and beat him. If family members are present, they’re attacked too,” a resident of Tartus told The Insider.

In December, protests by Alawites took place in Tartus, Latakia, Jableh, and Homs after a video surfaced of a fire at an Alawite shrine during the opposition’s capture of Aleppo. The fire occurred in late November, but the video spread on social media a month later. The protests led to clashes with police. In early January, former Assad-supporting soldiers ambushed and killed 14 security personnel of the new regime. In response, the new authorities imposed curfews and accused Assad loyalists of inciting unrest.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

Protests by Alawites in Latakia.

Photo: Sky News

“We are Alawites. That’s why we fear for our children’s future,” said a local in Latakia who wished to remain anonymous. “Alawites make up about 15% of the population. We used to feel completely safe, but now we’re scared. Of course we want to leave. But the question is, where?”

Changing attitudes toward Russians in Syria

The regime change has caused panic among Russians living in Syria. Many feel threatened because of their ties to the former Syrian government, military, or propaganda apparatus. Under Assad, Russians played a significant role in the country: they established the Khmeimim military base, conducted joint operations with the Syrian army, worked in state media’s Russian-language services, and taught Russian as a second language in schools. Portraits of Putin were sold alongside those of the former Syrian president in local markets.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

Russian military equipment near the Khmeimim base in Latakia.

Photo: Leo Correa / AP Photo

A woman working with Russia’s Foreign Ministry in Syria told The Insider: “I don’t feel safe. I fear for my children and grandchildren. The checkpoints have changed; there are new authorities wearing black armbands. It’s frightening to pass them, although I must say the people vary.” Nearly all Russians in Syria interviewed by The Insider said they do not feel secure.

After the opposition came to power, instructions on how to leave Syria — at a time when airports were still closed — flooded Russian community chats. Russia organized evacuation flights, with several planes departing from the Khmeimim Air Base in Latakia. However, officially, only some government personnel were reported to be evacuated. Two days before Assad was overthrown, Russians were advised to leave the country independently on commercial flights.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

Two days before Assad was overthrown, Russians were advised to leave the country independently on commercial flights.

“It’s chaos, vigilante justice. You often hear about people being dealt with as others see fit. If under the old regime you had enemies or someone who caused you trouble, now is your chance for revenge,” said Maria (name changed), a resident of the tourist town Mashtal Helu in Tartus province, home primarily to Christians.

“It’s calm for now, but there’s tension in the air. You feel like something is about to happen,” she said. Maria has lived in Syria for 20 years and has three children there. She stayed after the fall of Assad but evacuated her son to Russia due to threats.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

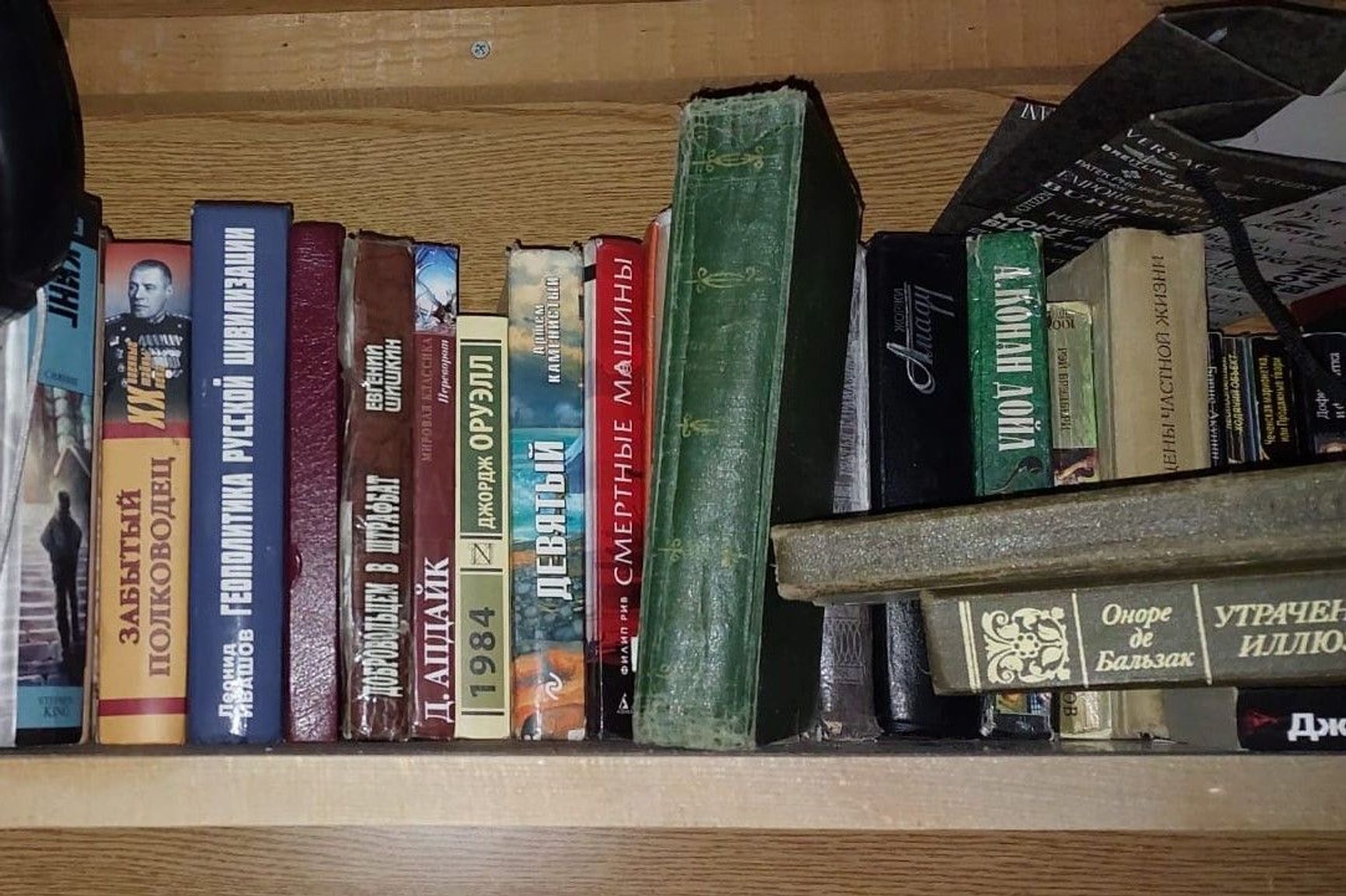

A bookshelf at an observation post abandoned by Russian troops.

“My eldest son worked as a military translator at our base,” Maria explained. “He always dreamed of becoming a translator. After finishing school, he didn’t even go to college — he started working with them. After everything that happened, it became impossible to live here. The threats became so frequent I had to take him out. We found someone coordinating the evacuation flights and got him on the list.”

The Russian Cooperation Agency, which is responsible for assisting evacuations, helped Russians and members of Russian-Syrian families leave Syria. Some fled to Russia as refugees without citizenship.

“My daughter left without a passport, as a refugee,” a Russian woman in Latakia told The Insider. “We couldn’t retrieve her passport because the embassy was blocked for security reasons. After she left, I managed to get her passport, but now I can’t send it to her, and she can’t start her studies under a scholarship.”

No incidents of persecution against Russians by the new authorities have been reported, and The Insider’s interviewees confirmed this. In fact, the opposition seems to be promoting the idea of tolerance toward Christians.

“The new [authorities] are going overboard with propaganda, acting like ‘we’re with you,’” said Maria from Mashtal Helu. “It’s over the top. Like, ‘You want a Christmas tree? Decorate two! We’ll add a third one, complete with fireworks and gunfire!’ It’s too much, and it makes me uneasy. But for now, they’re presenting themselves as friends, all nice and fluffy.”

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

Christians celebrate Christmas at the Church of Saint George in Maaloula.

Photo: Leo Correa / AP Photo

The exodus of Russians began long before the regime change, largely as the result of Syria’s catastrophic economic situation. Employees of state media told The Insider that salaries were meager, and bread was rationed using government-controlled coupons.

A Russian woman who worked for Syria’s state news agency SANA said she left Assad’s Syria for economic reasons and returned to her hometown of Krasnodar. “SANA’s Russian-language page launched in 2011, when the civil war began,” she noted.

“Now everyone will tell you everything is fine, for two reasons: either ‘our people came to power’ or ‘so it doesn’t come back to haunt me,’” she explained. However, she admitted that the situation isn’t as bad as initially feared and that the panic in the days following changing of the guard in Damascus was premature. “What I hear from my husband’s family and friends over the phone gives me hope,” she said.

Idlib: A glimpse of Syria’s future

The situation in Idlib offers insights into what Syria’s future might look like. Since 2017, the region has been under the control of the opposition, forming its own “government of salvation” and local administrative structures while operating without support from the Syrian state — and without a formal budget. Aid came from Turkey and various NGOs.

“Life was difficult, but not because the opposition oppressed the people. It was due to limited resources,” said Natalia, a doctor in the province.

Despite challenges that include an influx of refugees, war, and economic difficulties, Idlib became one of the most developed regions in the country after reintegration with liberated Syrian territories. “If you compare life in Idlib now with the Assad-controlled areas, it’s like night and day,” Natalia explains. “Idlib is objectively the most advanced and livable region [in Syria] because they started building a technocratic society, where leadership positions are held by experts in their fields, not politicians, bureaucrats, or someone’s relatives.”

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

One of The Insider's interviewees on an abandoned Russian tank. Photo from personal archive

Natalia details the path the province has taken under opposition control. According to her, progress is evident in nearly all areas of life — including healthcare, manufacturing, and agriculture.

“Initially, we had an energy system called ‘ishtirak,’ which means ‘cooperation.’ Someone with a large generator would sell power to others, connecting wires and installing switches. It was reliable. If one neighborhood lost power, you could go to another to get things done. Decentralization worked well during the war.”

The region saw the installation of centralized electricity in 2020 with the launch of Green Energy. “A lot of men immediately got jobs, and now they work day and night on the electricity,” says Natalia. “One time, an American drone damaged our power lines. They fixed everything in 40 minutes.”

Now, the province is fully supplied with electricity, and power is available almost around the clock — unlike in former Assad-controlled territories, where electricity is only provided for a few hours a day. In Idlib, the cost of electricity for residential use is $0.14 per kilowatt-hour. Many people relied on solar panels to survive, but these were frequently damaged by airstrikes.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

Workers install solar panels on the roof of a shop in Idlib, June 10, 2021.

Photo: AFP / Aaref Watad

The province is governed by Sharia law, Natalia explained. Alcohol sales are banned, unlike in former Assad-controlled areas. Public entertainment is also restricted, and there are no cinemas. Despite such dichotomies, Natalia told The Insider, she does not believe Syria will turn into “another Afghanistan.” The society here is fundamentally different, and women traditionally hold an important role: “In five and a half years, I’ve never witnessed road rage directed at a woman. If anyone dared to insult a female driver, other drivers would loudly and emotionally reprimand them,” Natalia said.

In recent years, shopping malls have been built in Idlib, offering a much wider range of goods than what was available in Assad-controlled areas. After the regime change, people from other provinces began flocking to Idlib for medical treatment, shopping, and medications. Consumer electronics, household appliances, and cars are imported from China and Turkey. “In Assad’s Syria, the import tax on a smartphone was as much as its full price, making them extremely expensive,” Natalia noted. “In Idlib, there are no such tariffs, so smartphone prices are comparable to those in Europe.”

Idlib also exported agricultural products independently from Assad-controlled Syria, with Spain becoming the primary importer of its olive oil. The region also produced corn, sunflower, and soybeans. Plans to cultivate cotton were disrupted by the war, but saffron farming began, with farmers being provided seeds for one of the world’s most expensive spices. “Here, they try to develop, while over there [in Assad-controlled territories], all they do is spread fear. They didn’t care about development. That’s the difference,” Natalia remarked.

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

A resident of Idlib province receives medical assistance at a hospital following a strike by Russian airstrike on a refugee tent camp in Saraqib on Oct. 23.

Photo: Syrian Civil Defense / الدفاع المدني السوري / Telegram

When Idlib first came under opposition control, the province had only four private and four public hospitals, Natalia recalled. Today, there are dozens.

“I remember when an Assad regime representative at the UN questioned reports of the 34 bombed hospitals mentioned by Idlib’s health minister, Munzir Khalil. He said, ‘How could there be 34 hospitals if there were only eight in Idlib?’ Khalil responded on Facebook, calling him ‘an idiot’ — that’s a direct quote — and told him that they’d actually opened 55!” Natalia noted.

It is also true that these hospitals frequently came under attack from the Assad regime and Russian Aerospace Forces. Natalia recalled the Russian airstrikes with horror:

“I was shocked when this so-called valiant Russian army arrived in 2015 to support a faltering regime that was already limping — on all four legs. The regime would have collapsed back then, but they prolonged its agony by another nine years.”

Unlike some of her compatriots, Natalia has no plans to return to Russia.

“Every day, transport planes fly in. We have a radar to monitor them,” she said. “What are they taking out? Everything the Russians brought in over these years. Just the kerosene for one of those planes costs enough to build an entire city in the Moscow suburbs — with amusement parks, hospitals, schools, and daycare centers. Dear compatriots, do you seriously believe your valiant forces are defending your country? Go back to your borders and defend them there. Develop your own country, plant crops on the abandoned lands overgrown with weeds, so you don’t have to buy potatoes from Egypt.”

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.

A Russian transport plane over Latakia.

Photo: Leo Correa / AP Photo

Olivia also has no plans to return to Russia, but hopes to one day see regime change in her homeland.

“God willing, one day in Russia we’ll wake up and hear someone say, ‘That’s it, the war is over.’”

The Alawites, a religious group linked to Shia Islam, are primarily based in Syria. Since Hafez al-Assad's rise to power in the 1970s, members of the community have occupied influential roles in Syria's military, political, and economic spheres. The Alawites were pivotal in supporting the former Syrian government and are predominantly located along the coastal regions, particularly in Latakia and Tartus.

The real name of the leader of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Muhammad al-Jolani, which he reverted to after taking power in Damascus.

Green Energy is a Syrian energy company operating in Idlib. It collaborates with private Turkish firms and plays a key role in providing the province with stable electricity.