A new front has opened in the Syrian civil war: smugglers associated with the ruling regime are now in a direct armed conflict with the army of neighboring Jordan. Maher Assad, the younger brother of Bashar Assad, may well be behind it all, leading a criminal syndicate that manufactures and sells the banned drug Captagon. Syria accounts for 80% of the world's Captagon production, exporting the substance concealed in live sheep and tea leaves. The business earns the Assad regime three times more money than all Mexican drug cartels combined. The Syrian leader needs the revenues. How else would he be able to afford the loyalty of his generals and officials?

Content

The king had three sons

The “Jihad Pill”

Captagon moves in mysterious ways

Drug manufacturers against drugs

Delivery with a fight

The king had three sons

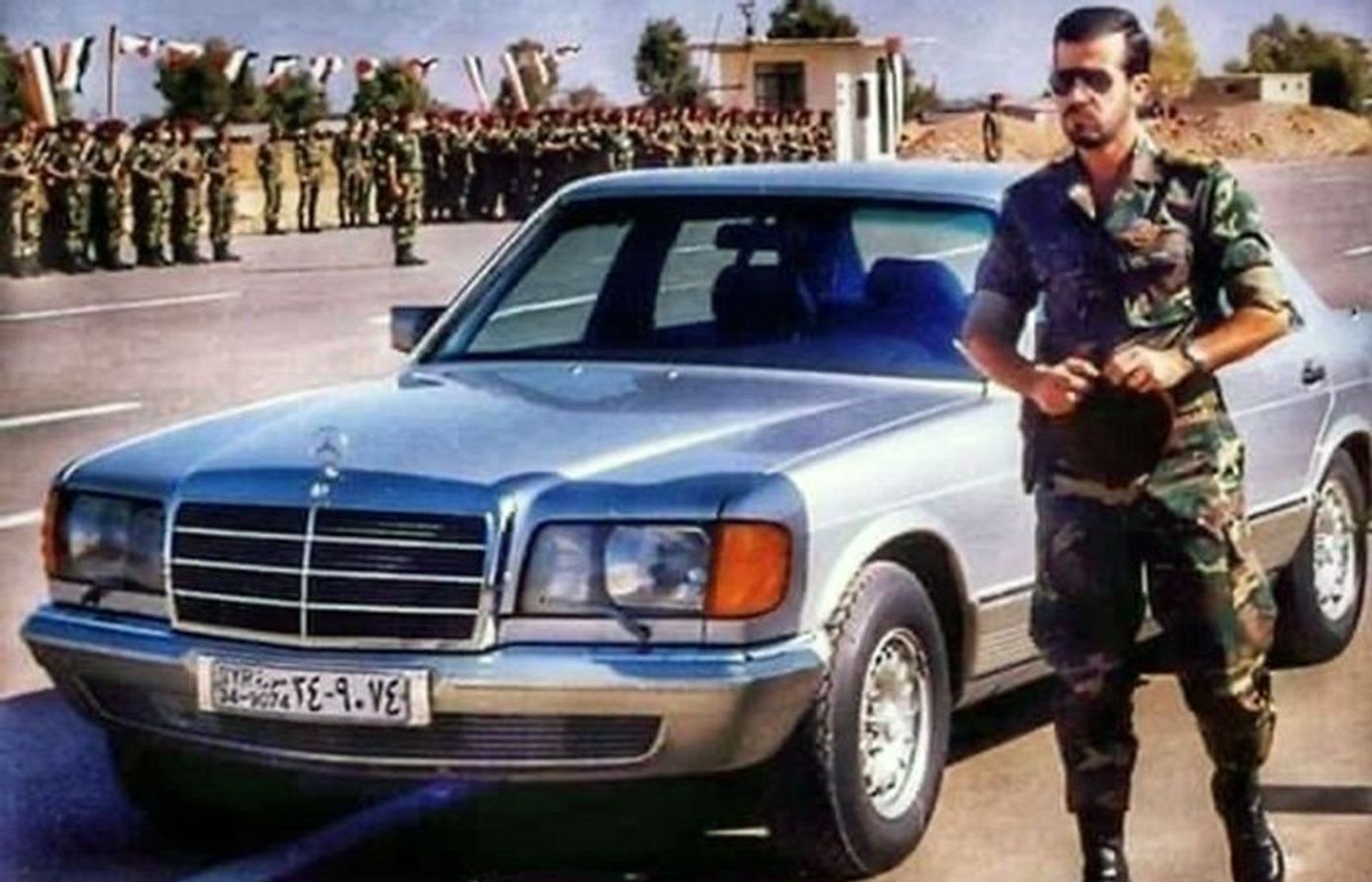

Early in the morning on January 21, 1994, Basil Assad, a young Colonel in the Syrian Army, got into his sporty Mercedes and headed off for Damascus International Airport. Basil, the eldest son of Syrian leader Hafez Assad and the dictatorial “president’s” official heir apparent, was scheduled to board a private plane to Germany en route to a ski vacation in the Alps.

Basil took some time gathering his things, and although the plane wouldn't have taken off without him, he hurried to make it to the airport before his special flight’s scheduled departure time. Patrol police, well acquainted with the young officer's Mercedes, wouldn't risk stopping the future president's car. Thus Basil raced along the capital’s foggy winter roads at speeds well exceeding the legal limit. His cousin, Hafez Maklouf, sat in the passenger seat next to the privileged driver.

Maklouf had fastened his seatbelt; Basil had not. On the highway leading to the airport, young Assad accelerated to 240 km/h before suddenly losing control of the car. The Mercedes skidded before crashing into a concrete median barrier at full speed. Basil died on the spot, while his passenger merely ended up in the hospital with serious injuries.

With the death of Basil, all the dynastic plans of the Assad family were buried. The efforts of propagandists, who for years had accustomed Syrians to the idea that the brave young colonel with the stylish beard would be their next president-for-life, had all been for nought. Having lost his beloved son and heir, Hafez Assad now had to choose a new successor.

Hafez had a limited range of options: the position of the president could be taken either by his middle son, Bashar, or the younger, Maher. Of the two, Maher seemed the more preferable successor. Like his father — and like the deceased elder brother — Maher had chosen a military career, was well-acquainted with the state’s armed forces, and actually lived in Syria. Bashar, on the other hand, had long since moved to London, where he was engaged in a private ophthalmological practice — a profession far removed from the military affairs so highly regarded by the men in his family.

Nevertheless, the father chose Bashar as the heir. The ophthalmologist was brought back from London and sent to study at the military academy in Homs. State propaganda began forming the image of the aging autocrat’s middle son as the nation's future hope.

In Syria, there is still a widespread conspiracy theory that the whole story of Bashar coming to power is the work of British intelligence

The story is so extraordinary that, in Syria, there is still a widespread conspiracy theory about the cascade of events that ultimately brought Bashar to power having been the work of British intelligence. According to this version, the British orchestrated the accident that killed Basil, then went all out to discredit Maher, all in pursuit of their aim: to bring the London-loving ophthalmologist — who, as the legend has it, was possibly recruited by the crown — to power in Damascus.

Whatever really happened to bring it about, after the death of Hafez Assad in the year 2000, middle son Bashar indeed assumed his father’s post. However, without the assistance of his militarily minded younger brother, it would have been much more difficult for Bashar to maintain control in a country torn apart by civil war and suffocated by international sanctions. After all, it is Maher who commands the country’s most combat-ready fighting force, the Syrian Army’s Fourth Armored Division, and it is also Maher who plays the leading role in the criminal schemes that provide his brother’s regime with the much-needed cash it needs to survive. As is often the case in the Middle East, Maher Assad is simultaneously a general and a gangster. He heads a criminal syndicate that manufactures and sells the illegal drug Captagon.

The “Jihad Pill”

Captagon emerged in the 1960s as a perfectly legal remedy for narcolepsy and attention deficit syndrome. These small pills contained as their active ingredient fenethylline, a relative of amphetamine. With a doctor's prescription, one could easily purchase them in European pharmacies — at least you could up until 1986, when the World Health Organization added the drug to its list of prohibited substances.

Official sales and production of the Captagon were halted. However, by that time, it had already gained popularity in the Middle East and Africa, where the youth consumed it recreationally. Illegal manufacturers quickly came up with a means of meeting market demand: Captagon was clandestinely produced in Bulgaria and then smuggled through the Balkan countries to its end consumers the Middle East.

Quite soon, Captagon found another application — as a kind of performance enhancing drug. Fighters from several of the irregular militias that proliferated in the Middle East in the late 1990s and 2000s began taking the tablets, which relieve fatigue and fear for several hours, help focus attention, and shut down the emotions that might otherwise hinder fighters’ actions in combat. The drug is also relatively inexpensive, with an average retail price of $3 per piece, even if a higher-quality, purified form purchased from dealers in Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates can cost up to $25.

These qualities make Captagon so attractive to combatants that the drug even acquired the unofficial nickname “jihad pill.” Hamas and ISIS combatants take Captagon, and it is also popular among members of Hezbollah and Al-Qaeda. Even Syrian rebels fighting against the Assad regime produce the drug for their own needs in makeshift conditions. However, Captagon produced in underground labs — and in actual Syrian pharmaceutical facilities — is distributed to the fighters of Bashar Assad's army. Interestingly, however, the quantities the country produces far exceed its own military’s demand.

This surplus — literally amounting to hundreds of millions of tablets — is smuggled to consumers in the Persian Gulf countries and Africa, where Captagon is still highly popular as a recreational drug. According to the British government, these shipments bring three times more money to the Assad regime than the revenues earned by all Mexican drug cartels combined.

Captagon shipments bring three times more money to the Assad regime than the revenues earned by all Mexican drug cartels combined

London estimates the value of the Syrian government's narco-empire to be $57 billion, which makes it one of the most valuable assets belonging to the Assad family and its inner circle. Of course, there are no official income figures for the Syrian leadership from the sale of the pills, but it is undoubtedly in the billions of dollars annually. At least $10 billion worth of Captagon is sold worldwide each year, and Syria accounts for 80% of the global production of the drug.

Revenues from Captagon assist Assad in buying the loyalty of officials and generals, as well as for funding weapon acquisitions. The regime's dependence on its substantial income from the shadowy Captagon empire is so significant that former U.S. Special Representative in Damascus Joel Rayburn referred to Syria as a “narco-state” and expressed confidence that, without money from Captagon sales, Bashar Assad would not have been able to hold onto power for so long.

For a long time, the main route for smuggling shipments ran through neighboring Lebanon, as the seemingly endless political crisis in Beirut was skillfully exploited by the Assad-allied Hezbollah group. In Lebanon, Hezbollah is a legal political organization represented in parliament and the government. Thanks to this status, Hezbollah had no serious trouble organizing contraband shipments of Captagon from Lebanese ports.

It is also possible that Hezbollah itself produced the drug in Lebanon for further shipment on to the Persian Gulf countries. These illicit shipments were one of the main causes behind the 2021 Saudi ban on the import of all Lebanese goods. Authorities in Damascus finally addressed drug trafficking largely due to concerns that other countries might join Saudi Arabia in taking action.

Captagon moves in mysterious ways

However, combating smuggling is a very challenging task, especially considering the Syrians' exceptional inventiveness in transporting Captagon. The drug is hidden in canned vegetables, tea leaves, and even in the entrails of live sheep. Thanks to these tricks, Syrian gangsters manage to conceal the majority of their product from anti-narcotics authorities.

According to France Press, in 2022, 90% of all pills exported from Syria reached the end consumer — this despite the fact that the number of intercepted pills is itself in the tens of millions. A single Syrian batch seized in Italy in the spring of 2020 consisted of 84 million pills. It is presumed that this batch was not intended for sale in Europe but was, as usual, slated to be smuggled to Africa.

In 2022, 90% of all pills exported from Syria reached the end consumer

By some estimates, this business gives Syria more money than its entire legal export, and the regime constantly works to increase its profits, primarily by expanding its market reach. To this end, criminal gangs associated with Damascus or Hezbollah have built distribution networks for Captagon in countries where the drug was not previously popular. Jordan is a primary focus. This country borders Syria to the north and Saudi Arabia to the south and east, making it highly attractive for smugglers as a transit One. Moreover, there is a growing local demand for Captagon in Jordan. According to official data, the number of drug-related crimes in the country increased from 2,000 in 2005 to over 20,000 in 2020, and the majority of these crimes are linked to Captagon.

The U.S. Department of State considers the export of Syrian Captagon to be one of the main sources of financing for Assad’s side in the ongoing civil war. Washington has even published detailed instructions on how to counter this illegal business.

But the effects have been negligible. Bashar Assad’s promise to end Captagon smuggling helped pave the way for the Arab League to renew Syria’s membership this past May (the country was excluded in November 2011 in the early months of the civil war), but the group again cut ties with Damascus in September. The reason for this re-cooling of relations was the Assad regime’s lack of action on the Captagon front.

Drug manufacturers against drugs

Assad and his inner circle vehemently deny their involvement in the illegal trade of banned substances, and regime-controlled media frequently report on victories of the security forces over drug dealers. However, beyond Syria, these statements are not readily believed. The U.S. Treasury Department regularly updates its sanction lists of people linked to the smuggling of the illicit drug, and these lists include high level officials in the Syrian government, including members of the Assad family.

Maher Assad, Bashar’s younger brother, has been under sanctions since April 2011, just weeks into the war. The accusations against him include both crimes of military brutality and offenses involving the illegal drug trade.

When the war broke out, Mahar commanded the Republican Guard, essentially the president's personal security force — replete with armored vehicles, artillery, and tens of thousands of soldiers and officers. It was the Republican Guard that was involved in brutal reprisals against the opposition, and Maher’s units guarded Damascus during the hottest days of the war, when rebels occupied the nearby suburbs of the Syrian capital.

After government forces pushed back their internal enemy, Maher received a new assignment. Since spring 2018, he has commanded the Fourth Armored Division — not only an elite military unit, but also a high-level criminal group engaged in looting, robbery, and smuggling — specifically, the smuggling of Captagon. As a European Union list of sanctioned Syrian individuals and entities states: “The Fourth Armored Division derives income, in part, from the trade of Captagon. The Captagon trade has become a business model controlled by the regime. It enriches a narrow circle of people belonging to this regime and is critically important for its existence.”If there was ever any bad blood between the brothers following Bashar’s elevation to heir apparent, it appears that Mahar has let go of the grudge.

According to a BBC investigation published last year, both rank-and-file members and officers from Maher's division are involved in the Captagon trade. While the former mostly act as street dealers, selling pills at retail, the latter are responsible for much more extensive operations. Officers serving under the president's brother are not subject to checks at the numerous checkpoints that have literally dotted the roads in Syria since the beginning of the war. This allows them to transport batches of pills in their vehicles, along with the smugglers who then move the Captagon across the border into Jordan.

Delivery with a fight

Jordanian authorities have attempted to engage in discussions with their Syrian counterparts on potential mutual efforts to combat drug trafficking. However, it is unlikely that the Jordanians were unaware that the people controlling the drug business in Syria were the same Syrian government officials sitting across from them at the negotiating table. When the talks fell through, Jordan deployed additional military units to secure its entire 375 km border with Syria.

This significantly complicated the task for smugglers, forcing them to adopt a new strategy. If previously smugglers attempted to cross the border quietly and unnoticed, retreating back into Syrian territory at the first sign of serious danger, now their only path forward involved fighting their way through. The first such clash occurred on December 12th, 2023. It ended with one Jordanian border guard dead, and another injured.

If previously smugglers attempted to cross the border quietly and unnoticed, now they are prepared to forcefully breach their way into Jordan

Less than a week later, on December 18, Syrian smugglers made another armed attempt to enter the territory of the neighboring state. Only the fierce fourteen-hour resistance of the Jordanian military forced them to retreat. After the battle, the Jordanians found discarded weapons left by the criminals, including sniper rifles and grenade launchers. Reportedly, the Syrians were under the influence of their own product, enabling them to maintain their attacks against the professional forces for so long.

These events leave little doubt that it was Jordan that was behind the airstrikes on Syrian territory in the second half of January. During these attacks, unidentified aircraft struck several targets in the province of As-Suwayda near the Jordanian border. Local residents reported that ten people, including children, were killed in the attack. Nothing is known about the involvement of any of the deceased in smuggling schemes.

The battle continues. Jordanian authorities intend to further strengthen border security with Syria, as was announced by the head of the state, King Abdullah II, during a recent inspection of the border military units. Interestingly, the attack by unknown aircraft on As-Suwayda occurred a few hours after Abdullah bid farewell to the border guards.

Jordan’s efforts have made it more difficult for the Assad family to deliver its illegal Captagon to buyers. However, the ruling clan is unlikely to simply give up the billions that have been helping the family remain in power in Damascus despite over a decade of war. There is still a sizable demand out there for Syria’s illicit export commodity, and the Assad regime will do what it can to meet that demand — no matter how much cruelty and destruction it might require.