In 1939 the USSR started a war with Finland, whose scenario now looks surprisingly similar to the invasion of Ukraine. The war with Finland was also supposed to be a rapid blitzkrieg, the success of which was ensured by the overwhelming superiority of the USSR's armed forces. The Finnish War was also presented as self-defense and a response to provocations. The propaganda also spoke about the benefits of the invasion for the civilian population, and the USSR planned to install a puppet government in Finland as well. Finally, that war, which too had been badly prepared, ended in total failure, with the troops suffering from lack of supplies and frostbite, being poorly motivated and sustaining much higher casualties. Ultimately, the USSR abandoned the conquest of Finland and limited itself to insignificant territorial gains.

Content

Preparation

Invasion

Hostilities

Bottom line

Losses

Preparation

In April 1938, a month after the Anschluss of Austria, the Soviet government expressed its desire to discuss security problems with the Finns. The USSR proposed that Finland allow the Red Army into its territory «to repel German aggression.» Otherwise, the Stalinist diplomats threatened (the talks were led by Boris Rybkin, NKVD resident in Helsinki, who acted under the guise of Yartsev, Second Secretary of the Embassy; the Finns were well aware of his true identity), the Soviet Union would not wait for the Wehrmacht to land on Finnish territory but would move its troops to meet the potential aggressor, turning Finland into a battlefield. The Finns rejected those proposals, pointing out they were incompatible with Finland's neutral status.

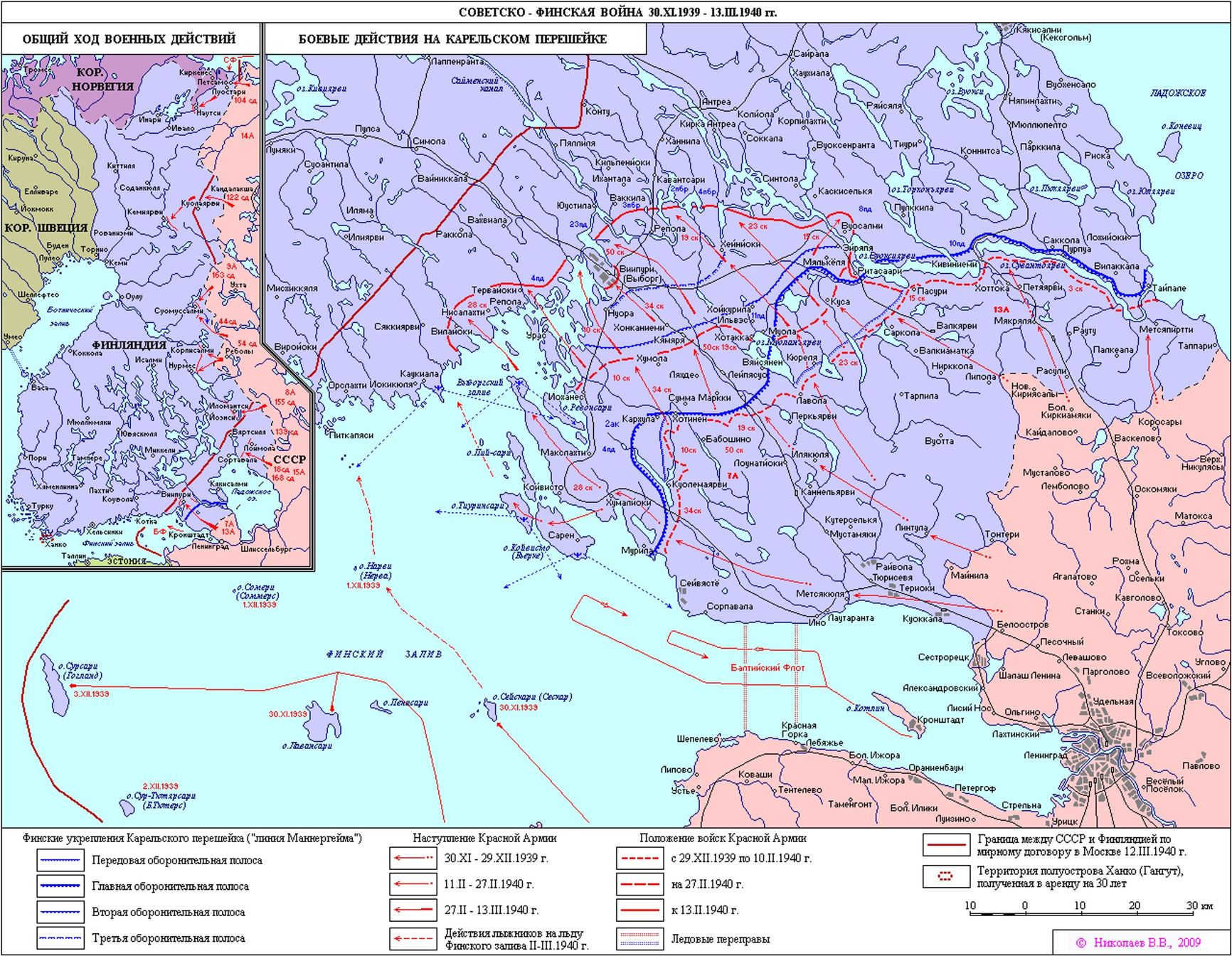

At the beginning of October 1938, shortly after the Munich agreement and the transition of the Sudetenland to Germany, the USSR generously offered Finland to equip its own bases on Gogland. The defense of the islands in the Gulf of Finland was to be taken over by the Soviet troops only in case the Finnish armed forces failed to cope with this task. The pesky Soviet concern was again rejected in Helsinki. After that both sides began to prepare more actively for military action. The war plan drawn up at the headquarters of the Leningrad military district in March 1939 provided for the capture of Vyborg already on the 10th day of the offensive, which should have paved the way to Helsinki for the Soviet troops.

The war plan called for the capture of Vyborg on the 10th day of the offensive, which would have paved the way to Helsinki for the Soviet troops

It was thought that Finland would not be able to resist the USSR for any length of time because of the enormous inequality of forces. After all, the population of Finland in 1939 was 3.7 million people, while the population of the USSR at the time exceeded 180 million. The Finnish army had virtually no tanks, and only a small number of aircraft. The Red Army, on the other hand, had more tanks than all the armies of Europe combined, and ranked first in the world for the number of warplanes. At the end of June 1939 the commander of the Leningrad military district, army commander 2nd rank Kirill Meretskov was summoned to Stalin, who ordered him to prepare «a plan for covering the border from the aggression and delivering a counterstroke against the Finnish armed forces in case of the military provocation from their side» and warned that «this summer we can expect serious action from Germany». Otto Kuusinen, Secretary of the Executive Committee of the Comintern, was present during the conversation. Stalin ordered Meretskov to consult with Kuusinen on all matters relating to Finland.

On August 23, Stalin's long-awaited «serious action on the part of Germany» finally materialized. Ribbentrop and Molotov signed the infamous non-aggression pact. In a secret additional protocol, the Soviet Union and the Reich divided Eastern Europe, with Finland included in the Soviet sphere of influence. After Hitler and Stalin had «fraternally» divided Poland, it was the Baltic States' turn. Between September 28 and October 10, 1939, the Soviets concluded treaties of mutual assistance with the governments of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, which provided for the establishment of Soviet military bases there. On October 5 a similar offer was made to Finland, but the Finns rejected it. On October 11, Juho Paasikivi, Finnish envoy to Sweden, arrived in Moscow to negotiate. He was later joined by Social Democrat leader Väinö Tanner, then Finance Minister. In September, the Soviet Union held a covert mobilization in connection with the invasion of Poland and the possible future occupation of the Baltic States. In turn, the Finnish government in September recalled reservists who had just been discharged from service. The conscription of reservists to the Finnish army units located near the Soviet border took place on September 23.

On October 7, the German Foreign Ministry sent a memorandum to the Finnish government, which stressed that the Reich would not interfere in any way in the relations between Finland and the Soviet Union. England and France offered Helsinki diplomatic support. But since they were at war with Germany and the Baltic Sea was controlled by the German navy, London and Paris could not provide direct military assistance to Finland. On October 14 the USSR demanded that Finland agree to a 30-year lease of the Hanko peninsula, the key to Helsinki, and the islands in the Gulf of Finland, parts of the Rybachi and Sredny peninsulas and the Karelian Isthmus up to the Vuoksa river and the Koivisto peninsula – a total area of 2761 square kilometers - in exchange for the Soviet Karelian territory around Rebola and Poros Lake, a total area of 5,528 square kilometers. The Finns refused. Otherwise, they would have had to give up not only heavily populated areas with well-developed infrastructure but also the major fortifications of the Mannerheim line, which would have left the capital of Finland unprotected in case of a Soviet attack. Whereas in return they would have received sparsely populated territory with forests and swamps.

On October 19, the Finnish delegation proposed a compromise, agreeing to cede five islands to the USSR and to move the border 10 km further away from Leningrad, but refused to cede the Hanko Peninsula and Lappvik Bay, because ceding those territories gave the Soviet side control over Helsinki. But the compromise did not suit Stalin. On October 11 Field Marshal Karl Gustav Mannerheim, who had been appointed commander of the Finnish defense forces the day before, suggested a covert mobilization, under the guise of a training campaign, since the Soviet troops were already mobilized and were moving toward the Finnish border. Voluntary evacuation of the population from Helsinki as well as from the border areas on the Karelian Isthmus began. In the second half of October the Finnish troops were partly mobilized with the formation of nine divisions and several separate battalions and brigades.

At the beginning of November, the Finnish side rejected a proposal that Finland and the USSR should mutually disarm their fortified areas on the Karelian Isthmus leaving only ordinary border guards there. As Finland had no intention of attacking the USSR, the implementation of this proposal would only have led to its disarmament in the face of the forthcoming Soviet aggression. On October 29, the Military Council of the Leningrad Military District submitted to Defense Commissar Voroshilov a «Plan of Operation for the Defeat of the Finnish Army Land and Marine Forces». On November 13 the Finnish delegation left Moscow without reaching an agreement. In this regard, Stalin said on the same day at the Main Military Council: «We will have to go to war with Finland». On November 15 Voroshilov ordered that the concentration of troops be completed by November 17. It was declared that the aim of the operation was to «swiftly defeat the enemy's opposing land and marine forces». And on November 21 the troops of the Leningrad District and the Baltic Fleet received a directive of the Military Council of the Leningrad Military District. They were ordered to begin the offensive, its plan to be presented on November 22 (at the same time an order was given to begin an advance on the border). The operation was supposed to planned at three weeks. At the same time, it was specified that «a special instruction will be given about the time of the offensive,» and that «the preparations for the operation and the initial positions of the troops should be kept secret, observing all the camouflage measures». But the rumors about the impending Soviet attack were widely circulating among the civilian population of the frontier regions. On October 25, 1939 the formation began of the 1st corps of the Finnish People's Army, which was supposed to serve as the embryo of the army of the puppet Finnish Democratic Republic (does that ring a bell?), headed by Kuusinen. The corps was formed of the USSR's ethnic Finns and Karelians, but it included many fighters and commanders of Russian and other ethnicities.

Invasion

To create a pretext for an attack on Finland, Stalin arranged a provocative shelling of the Red Army's positions in the vicinity of the village of Mainila on the Karelian Isthmus on November 26, 1930. Nikita Khrushchev recollected the day when this provocation took place: «All of a sudden a phone call came that we'd fired a shot. The Finns responded with artillery fire (in reality the Finnish side did not open fire - B.S.). In fact, a war had broken out. I say this because there is another interpretation: the Finns were the first to fire and so we had to respond. Did we have the legal and moral right to act like that? Legally, of course, we had no right. Morally, the desire to protect ourselves, to reach an agreement with our neighbor, justified us in our own eyes.» The Finns insisted their observers had seen that on that section of the frontier artillery shells were fired from Soviet territory. The Soviets claimed that four Red Army servicemen were killed and eight wounded. Later Russian historians found out that the 68th rifle regiment, which was stationed near Mainila, did not suffer any losses on November 26, as the number of its soldiers did not change in the following days until the beginning of the war. On November 30, the Soviet troops invaded Finland on a broad front, almost along the entire border line.

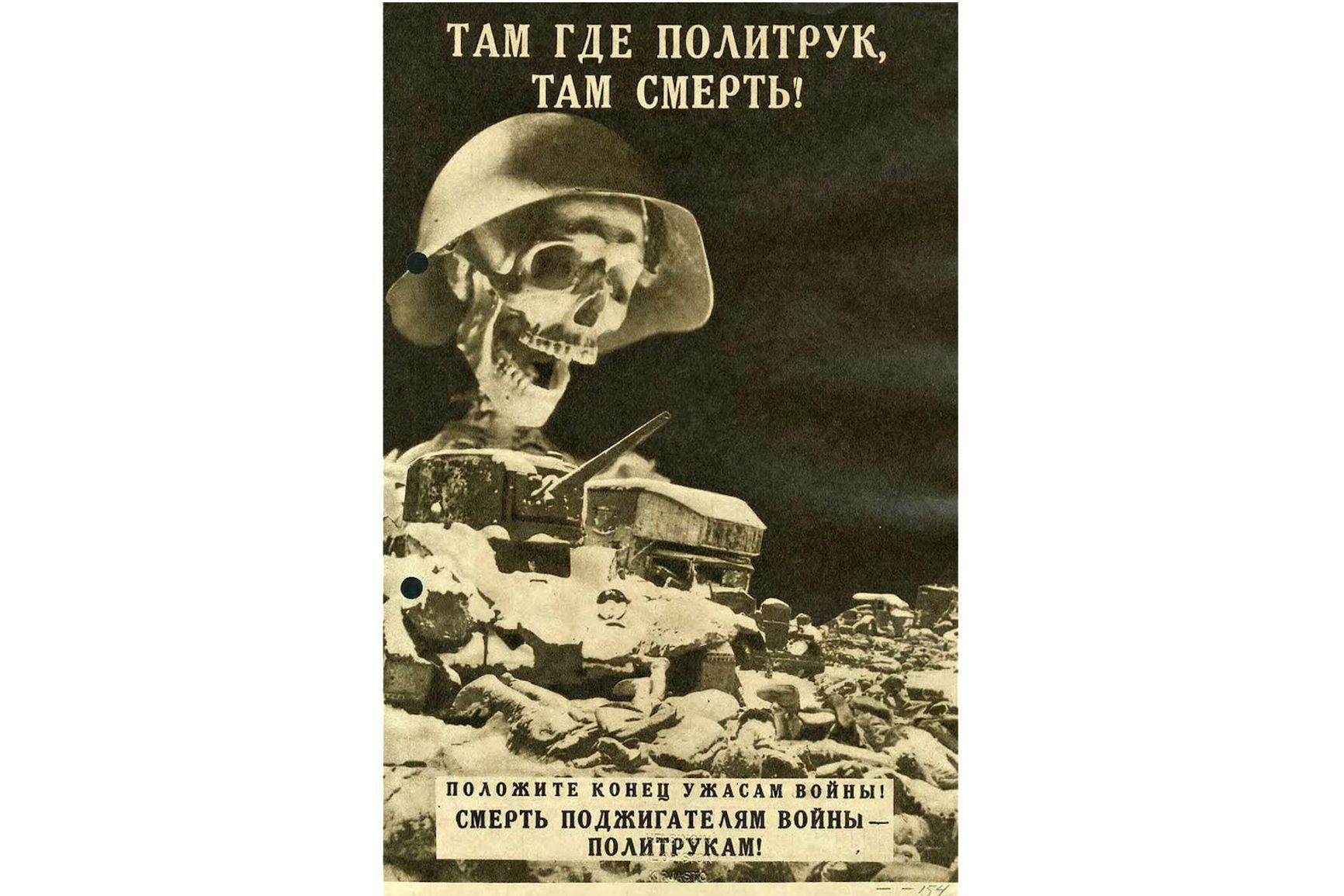

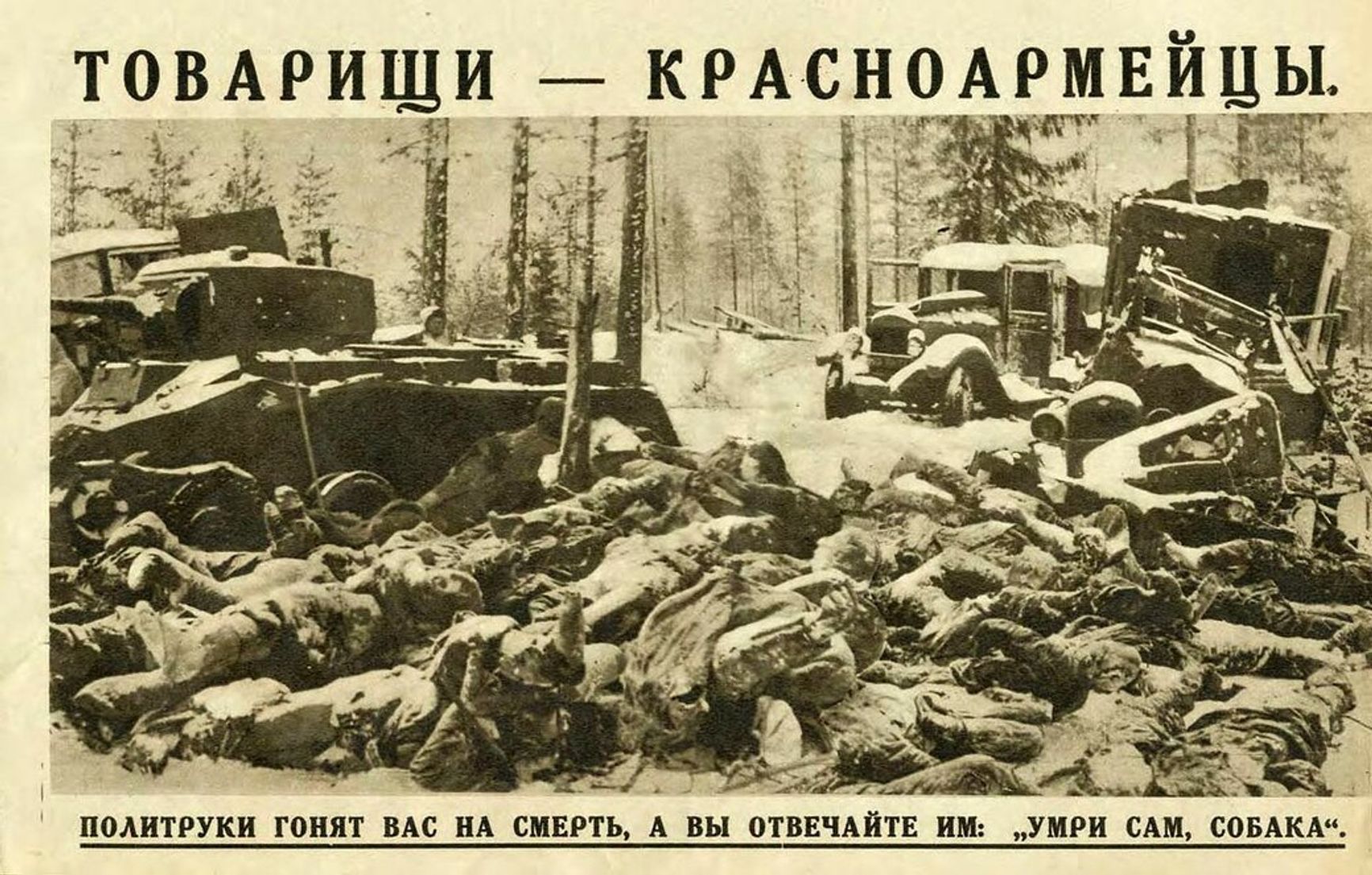

Finnish Winter War leaflet

On December 1, 1939, at 9.50 p.m., TASS reported on the formation of a new Finnish government. The next day the Soviet newspapers reported that, according to a radio intercept, «today in the city of Terijoki (occupied by the Red Army on the Karelian Isthmus. - B.S.) by agreement of several left-wing parties and rebellious Finnish soldiers a new government of Finland - the People's Government of the Democratic Republic of Finland, headed by Otto Kuusinen, has been formed.» On the same day, Pravda published a statement of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Finland, which said: «The whole working class, peasantry, craftsmen, petty traders and working intelligentsia, i.e. the vast majority of our people, must be united into one Popular Front for defending their interests, and a government of the working people, based on that front, i.e. a People's Government, must be brought to power.» When the Soviet Union was accused in the League of Nations of aggression against Finland, Moscow replied that the USSR was not at war with Finland, but on the contrary had concluded a treaty of friendship and mutual assistance with the government of the Democratic Republic of Finland. Stalin tried to portray what was happening in Finland as a civil war between the White and Red Finns, and the Red Army, it was said, had responded to the Red Finns' request for help.

Stalin tried to portray what was happening in Finland as a civil war between the White and Red Finns, and the Red Army, it was said, responded to a request for help from the Red Finns

As a matter of fact, the Sovietization of the Transcaucasian republics in 1920-21 followed the same pattern. But this time the ploy failed, and on December 4 the USSR was expelled from the League of Nations by a majority vote. Of the sanctions taken against the USSR, the most serious was the U.S. embargo on the supply of high-octane gasoline, which, among other things, severely limited the training of Soviet pilots on the eve of the German invasion in June 1941. But it seems Stalin wanted to use the FDR government not only for external propaganda purposes, but he also seriously expected this puppet government would gain a fairly broad support in Finland and assist in the disintegration of the Finnish army. He was completely wrong. The Finnish people rallied around their government and army. There was practically no desertion or voluntary surrender. Moreover, the Communists who had participated in the Finnish Civil War in 1918 volunteered to serve in the Finnish army. In contrast, on the Soviet side the Red Army servicemen were poorly motivated to fight against Finland. Stalin counted on a blitzkrieg and a lack of strong resistance, like during the Red Army's «Polish campaign» in September 1939, when the Polish army, defeated by the Germans, was unable to mount any serious resistance. That is why there had been no serious propaganda campaign for the war with the Finns. It was belatedly launched just a few days before the attack, after the provocation in Mainila. At the beginning of the war there were many cases of desertion and voluntary surrender in the Red Army. The NKVD barrier troops had to stop those who tried to flee the battlefield throughout the war.

Hostilities

At the beginning of combat operations, the Red Army outnumbered the Finnish troops, numbering 426,000 men, excluding the Baltic Fleet, compared to about 250,000 Finnish soldiers. By the end of the war the number of the Soviet troops was nearly 900,000, and the number of Finnish troops increased to 265,000. In total, taking into account the losses, up to 1.4 million Red Army servicemen and up to 340,000 Finns participated in the Winter War.

The Red Army attacked the Karelian Isthmus aiming for the Finnish capital Helsinki. An ancillary strike was delivered north of Lake Ladoga. Here, on hard terrain, the Soviet troops acted extremely unsuccessfully. Finns managed to encircle a few Soviet formations and took many prisoners. Only the actions of the 14th Soviet army in the polar region were successful. It seized the only Finnish port in the Barents Sea, Petsamo, but was unable to advance further in the tundra conditions. The storm of the Mannerheim line on the Karelian Isthmus by December 30, 1939, ended in a complete failure. Only a few minor incursions were made. The Soviet command had very little idea of the Finnish fortifications. The assault resumed on February 1, 1940 after the number of Soviet troops on the Karelian Isthmus more than doubled and all the forces acting against Finland were united into a North-Western Front under the command of Army Commander 1st Rank Semyon Timoshenko. In the last decade of February, the Mannerheim line was breached. On March 13, the day the peace treaty was signed, the fighting continued on the rear defense line near Vyborg. That day the Soviet troops made an unsuccessful and completely pointless attack on Vyborg, which, according to the terms of the Moscow peace treaty, signed the day before, was to be handed over to the Soviet Union anyway.

Finnish Winter War leaflet

The Finnish Army showed a much higher level of military training, command, communications and logistics, and the ability to interact on the battlefield. The Finnish troops were highly motivated to defend their country and were extremely zealous in combat training, including the reservists. The combat training system was largely based on the experience of the German land army, where a number of Finnish soldiers and officers had served as volunteers during World War I in the 27th Jaeger battalion. At the time, the German land army was the best in the world in terms of organization and training. Finnish aircraft were not inferior to Soviet aircraft, and the level of training of Finnish pilots was superior to that of the Soviet pilots. Therefore, the Red Army Air Forces, despite their numerical superiority, were unable to gain air supremacy.

The Finnish army was almost exclusively on the defensive, launching only local counterattacks. Wider counterattacks were launched only north of Lake Ladoga and resulted in the encirclement of several Soviet divisions and brigades.

The Western powers began to help Finland only after they were convinced it had withstood the first Soviet strike (doesn't it ring a bell, again?). Supplies from England, France, Sweden, Italy and some other countries were significant and included aircraft, field and anti-aircraft artillery. As for other kinds of armaments, Finland managed to provide for itself, particularly by using captured trophies. So, most of the 55 tanks used by Finns were captured Soviet tanks. During the war Finland received 77,300 rifles from abroad, while 82,570 rifles were produced domestically. The role of trophies was more significant than foreign aid: trophies accounted for nearly 15% of all rifles, 4% of submachine guns, 17% of hand guns and two-thirds of machine guns, a third of anti-tank guns, over half of the field guns, and 6% of all mortars received by the Finnish army during the war. In an interview with the French newspaper Excelsior the commander of the Lapland Group, Finnish Major-General Kurt Wallenius, when asked about the largest supplier of military equipment to Finland, answered: «The Russians, of course!»

Finnish Winter War leaflet

Finland's economy suffered little or no damage from air raids due to their ineffectiveness. Until the end of the war the aviation plant in Tampere (192 tons of bombs dropped on the city), the armament plant in Kuopio (87 tons), the largest power station in Imatra (78 tons) and most of the enterprises fulfilling military orders continued to operate. The transfers of reserves, reinforcements, equipment and weapons to the front, as well as the delivery of materiel and military equipment from Sweden were never interrupted or at least slowed down. More than 11,000 foreign volunteers came to Finland towards the end of the war, but they did not play a significant role in the war.

When Soviet troops returned to the Lemetti area, which had been ceded to the Soviet Union following the peace treaty, they found a gruesome scene at the place where wounded Red Army soldiers had been left. Some of the dugouts were destroyed with grenades, others were burned. The Red Army command blamed the massacre on the Finns. However, even before the end of the war, the Finns blamed the Soviet side for the massacre of the wounded Red Army soldiers. The leaflets distributed at the front among the Red Army servicemen said in particular: «At Pyatkiranta your wounded comrades received neither care nor food. They complained in a legal manner, but they were shot.» The question of who killed the Soviet wounded soldiers cannot be considered completely clear. But it seems unlikely the Finns would have dared to write about the killings of the Soviet wounded soldiers in the area occupied by the Finns, had they not been certain it had been done by the Soviets.

Bottom line

According to the March 12 peace treaty, signed in Moscow, the Soviet Union received the Karelian Isthmus with Vyborg, the Gulf of Finland islands and certain territories in North Karelia with a total area of nearly 40,000 square kilometers, i.e. about 10% of the prewar Finnish territory. The Hanko peninsula was leased to the Soviet Union for 30 years to establish a naval base there. However, Finland retained its independence and its armed forces. Stalin refused to conquer Finland at once, because the Finnish army, despite the loss of the Mannerheim line, was still able to resist at least for a few weeks. Had it managed to hold out until the spring thaw, the Soviet offensive would have halted for a while. And with a German offensive on the Western Front expected by May 1940, Stalin wanted to free up the main forces of the Red Army to stab the Germans in the back at the right moment if they got stuck on the Maginot Line. In addition, London and Paris were seriously considering sending an expeditionary corps to help Finland, and Stalin did not want a direct clash with the Franco-British forces, as he viewed England and France as potential allies against Hitler.

Losses

According to alphabetical lists of the Red Army soldiers who died from wounds or did not return from captivity, the Soviet losses in the Soviet-Finnish War constituted 131,476 people (according to Pavel Aptekar's calculations). But there is reason to believe that about 20-25% of the dead were not included in the alphabetical lists. Then the total number of casualties can be estimated at 170,000 people, which is quite close to the Finnish estimate of the number of Soviet casualties, 200,000. The Finnish army losses were 22,810, including those who were killed in action and who died by other causes. 876 Finns were taken prisoner. According to different estimates, from 5,546 to 6,116 Red Army soldiers were taken prisoner in Finland. There were 1,029 casualties among the Finnish civilian population as a result of the Soviet shelling and bombing of Helsinki and some other cities, including 65 sailors of the merchant fleet whose ships were sunk and 68 female nurses.

Nearly 400,000 Finns fled the territories occupied by the Red Army, i.e. over 10% of the population. Another 150,000 people were evacuated from Helsinki because of the air raids. In total, about 15% of the population of Finland became refugees.

If we compare the Winter War and the Russian «special operation» in Ukraine, the similarities are striking. The Russian General Staff seems to have seriously hoped that the Ukrainian army, except for the volunteer battalions of the National Guard, would not offer any serious resistance and would prefer to either return to their homes or surrender. According to U.S. intelligence forecasts, based on Russian sources, the Russian army was expected to enter Kiev within 96 hours after the outbreak of hostilities. Pro-Russian sentiment in Ukraine was greatly overestimated, just as support for the Communists and the USSR among the Finnish population had been overestimated back in 1939. The invasion of Ukraine followed the same pattern as the invasion of Finland - as an aid to the formation of a puppet state. And, of course, the Russian military and political leaders massively overestimated the combat capability of the Russian army and underestimated Russia's potential human losses, the capability of the Ukrainian army, the Ukrainian people's will to resist the invasion, and the degree of Ukraine's national and political consolidation.