On May 26, Qatar helped bring 68 Ukrainian children back home after acting as a mediator in talks with Russia. Qatar's role as a go-between has also become a crucial part of efforts to resolve the bloody conflict in the Gaza Strip. With its vast natural gas reserves, sophisticated media strategy, and assertive foreign policy, Qatar has emerged as a major player on the global stage — undeterred even by a blockade attempt from fellow Gulf monarchies. After all, just two weeks ago, Qatar was a key stop on U.S. President Donald Trump’s Middle East tour — a trip that was highlighted by the tiny emirate’s ruling family giving the American leader a $400 million airplane.

Content

A path to power

Backing the Islamists

An indispensable mediator

Qatar and the war in Ukraine

Image is everything

More than business

A path to power

For years after gaining independence from Britain in 1971, the small emirate of Qatar barely registered on the regional political agenda of the Persian Gulf, let alone on the international stage. That began to change in 1995, when Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa came to power following another palace coup. Among his early priorities were economic reforms, including major investments in emerging technologies — liquefied natural gas (LNG) production chief among them.

The discovery of new gas fields gave Doha the resources and confidence to step into international affairs. By 1996, Qatar had already become a key supplier of gas to Japan and Europe, both of which were in urgent need of alternative energy sources.

Gas exports not only brought in billions of dollars but also dramatically increased Qatar’s political leverage. Shaping the country’s image became central to Sheikh Hamad’s strategy. A cornerstone of that effort was the creation of Al Jazeera in 1996 — a television network whose name means “the island” in Arabic. Launched on the emir’s orders, it went on to spark a media revolution across the Arab world.

Real-time news updates, in-depth on-the-ground reports correspondents stationed across the Arab world and beyond — these became Qatar’s answer to the “CNN effect,” named in honor of the American network that broadcast the 1990–1991 Gulf War live.

Before Qatar launched its media venture, the Arab world had never boasted a news outlet with such scale and quality. Al Jazeera — not Western media — was frequently blamed by various rulers across the region for «subversive» coverage targeting their regimes. It’s no coincidence that during the so-called “Qatar crisis” of 2020, Saudi Arabia and its allies began by closing airspaces, expelling diplomats — and banning Al Jazeera.

Al Jazeera media conglomerate logo

As Qatar deepened its economic ties with the West — chiefly with the United States, which had backed Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa’s rise to power — it soon expanded its role into the military sphere. After so many Saudi nationals were discovered to have been among the terrorists who carried out the attacks of September 11, 2001, Washington began looking for alternatives to its Saudi military bases. In 2003, Qatar’s Al Udeid air base fit the bill and was eventually transformed into the headquarters of U.S. Central Command.

Today, Al Udeid is the largest air base in the Middle East. In 2024, the U.S. reached an agreement with Qatar’s leadership to maintain its military presence there for another decade.

Backing the Islamists

Despite its growing alignment with the West, by the late 1990s Qatar’s leadership had begun betting on political Islam and lending support to Islamist movements around the world. Chief among these was the Muslim Brotherhood, an Egyptian movement founded in the 1920s that had, over the decades, established networks in dozens of countries. It remains active: a report released by French authorities on May 21 of this year stated that organizations and foundations linked to the Brotherhood were actively lobbying in an effort to influence EU institutions.

By the early 2000s, Islamist movements had gained broad popularity in the Arab world amid rising anti-Western sentiment following military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. “The Arab street” increasingly saw these movements as an alternative to long-standing authoritarian regimes like those of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, and Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia.

For years, Al Jazeera aired a weekly program called “Al-Sharia wa al-Hayat” (“Sharia and Life”) featuring Yusuf al-Qaradawi, the Egyptian preacher and spiritual leader of the Muslim Brotherhood. His sermons, frequently broadcast on the channel, sparked controversy around the world — including inside many Muslim communities.

Al-Qaradawi opposed suicide bombings by Muslims in general, but he described attacks by suicide bombers in Israel not as terrorism, but as “acts of great heroism.” These and similar statements led to travel bans from the United Kingdom, France, and several other Western countries.

The Islamist movement’s moment came during the 2011 Arab Spring, when underground Islamist factions began to take power following the fall of Middle Eastern dictators. Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, and Libya were among the states to see the rise of Islamist parties.

Qatar, alongside Turkey, actively supported the Islamists’ ascent. If Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) offered a political model for blending Islam with democracy, then Doha provided the financial and media support. Al Jazeera gave extensive coverage to Arab Spring protests, often amplifying their scale. But these efforts sometimes had a negative effect, leading to a loss of credibility among segments of its audience and eventually resulting in outright bans by countries like Bahrain, Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia.

Al Jazeera gave extensive coverage to all the Arab Spring protests, often exaggerating their scale

Even though Islamists failed to hold onto power in any Arab country — the Muslim Brotherhood was banned in Egypt after being overthrown — Qatar continued to support them.

An indispensable mediator

In 2012, after being expelled from Syria for opposing Bashar al-Assad’s regime, leaders of the Palestinian militant group Hamas — originally founded in the late 1970s as a Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood — set up a new headquarters in Qatar.

Each time conflict in Gaza flared up between Israel and Hamas, Qatar emerged as a key sponsor of reconstruction in the Palestinian enclave, providing up to $30 million a month to the militants — ostensibly for rebuilding, though in practice the funds may also have been used to strengthen Hamas’s military capacity.

Each time conflict flared up between Israel and Hamas, Qatar became the primary sponsor of reconstruction efforts in the Palestinian enclave

Moreover, a high-profile investigation is currently underway in Israel into suspicions that a senior adviser and a spokesperson for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did work for Qatar in exchange for favors. The probe centers on alleged payments from a U.S. lobbying firm acting on behalf of the emirate, with the money supposedly changing hands in return for public relations services provided to the Qatari government.

Whatever the outcome, Doha remains a central player in mediation efforts around Gaza. In January 2025, it was Qatar’s joint prime minister and foreign minister, Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani, who announced a deal between Israel and Hamas. Although that deal had collapsed by early March, the emirate continues to be seen as a likely venue for reaching a new agreement.

In the early 2000s, Qatar's leadership established similarly close ties with the Taliban. In 2013, the Taliban’s political office opened in Qatar, becoming the hub for so-called moderate elements within the movement. As a result, Doha emerged as the principal intermediary between the Taliban and the United States. It was here, in February 2020, that the two sides signed the Doha Agreement, under which Washington pledged to withdraw its forces from Afghanistan in exchange for a halt to terrorist activity by the militants.

A U.S.–Taliban agreement on the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan was signed in the Qatari capital, Doha

After the Taliban established full control over Afghan territory in late summer 2021, Qatar hosted all major international conferences on the country's future — including those held under UN auspices.

Despite Doha’s critical stance on the Taliban’s initial moves, which Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani described as “disappointing and a step backward,” Qatar remains their most important foreign partner. Notably, in May 2023, Qatar’s prime minister became the first foreign politician to hold secret talks with the Taliban’s supreme leader, Hibatullah Akhundzada, who until then had never appeared in public, according to a Reuters report.

Qatar and the war in Ukraine

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Qatar’s leadership — like that of other Gulf monarchies — took a cautious stance. On the one hand, Doha did not condemn Moscow for its aggression against Kyiv and did not join the sanctions against Russia. Instead, it maintained business ties with Russia and has invested around $13 billion in the Russian economy. But on the other, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani urged Vladimir Putin to respect Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The emirate allocated $100 million in humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The emirate allocated $100 million in humanitarian aid to Ukraine, while investing around $13 billion in Russia’s economy

Since October 2023, Qatar has also served as a mediator between Moscow and Kyiv in efforts to return Ukrainian children who were unlawfully taken from their country. Dozens of children have already been returned to Ukraine via the Qatari embassy in Moscow. The emirate’s authorities view this mission as their contribution to “strengthening peace, security, and stability” in the region and globally.

Image is everything

Qatar’s active role as a mediator is part of a broader strategy to boost its international image. But diplomacy isn’t the only tool being used.

In December 2022, a scandal broke out in the European Parliament involving several EU officials and members of their families. They were suspected of working in the interests of several foreign countries, including Qatar.

According to released documents, from 2018 to 2022, individuals influenced by Doha succeeded in overturning six parliamentary resolutions that had condemned Qatar’s human rights record.

Much of this effort was aimed at polishing the emirate’s reputation ahead of the FIFA World Cup, which was held in Qatar in November–December 2022.

Opening ceremony of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar

Meanwhile, according to numerous reports by human rights organizations, migrant workers involved in preparations for the World Cup were routinely subjected to serious labor abuses, including the absence of rest days, disproportionate financial penalties, underpayment for overtime, hazardous working conditions, substandard living conditions, and discrimination based on race, nationality, and language. There were also reports of worker deaths.

Those responsible have yet to be identified — let alone held accountable. FIFA President Gianni Infantino from calling the 2022 World Cup in Qatar “unique” and “perfect.”

More than business

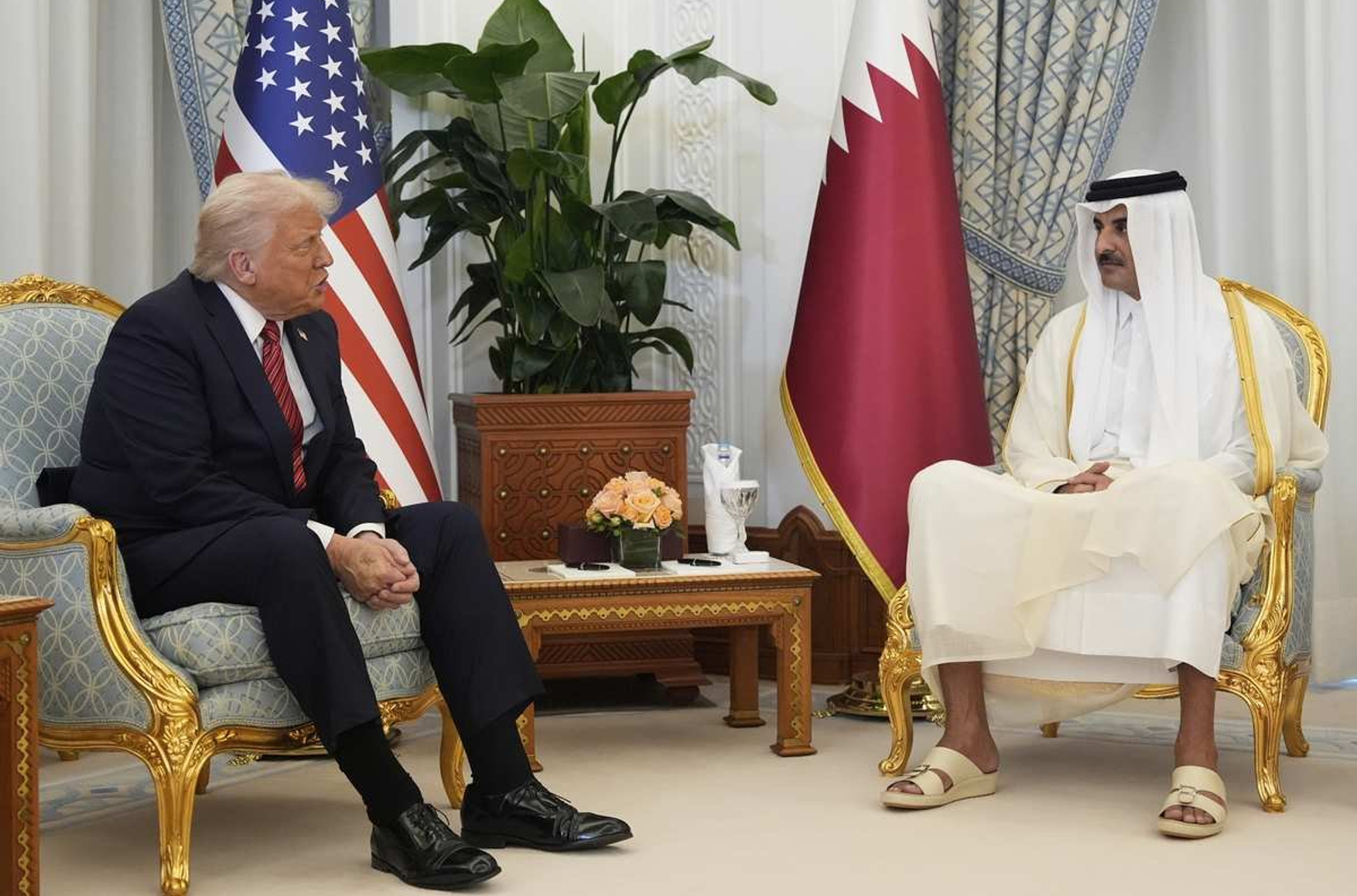

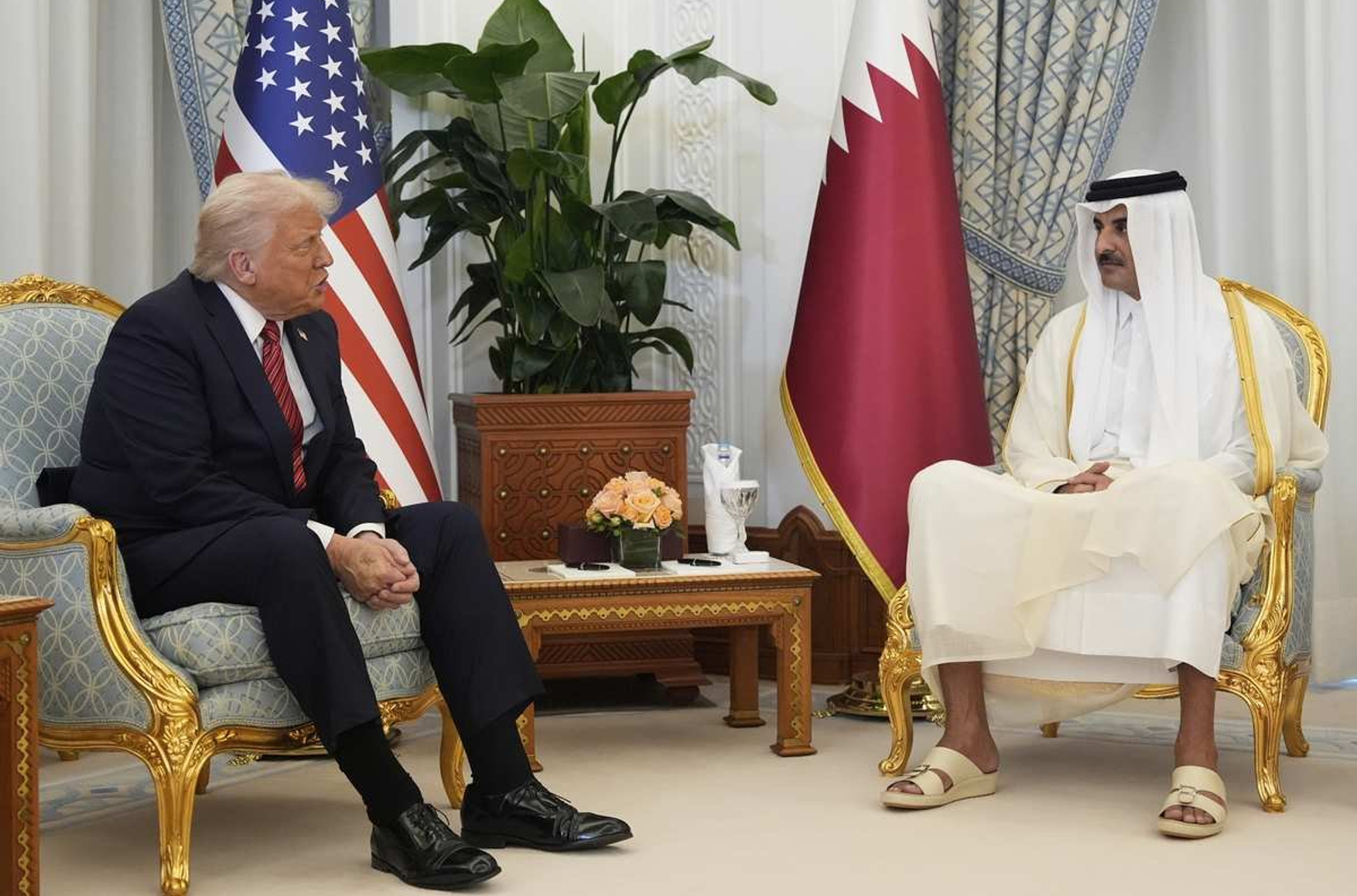

Donald Trump’s visit to the Middle East in mid-May was the first foreign trip of his current term — just like it was the last time around. In 2017 Trump visited Saudi Arabia, and immediately afterwards, four Arab states — Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the UAE, and Egypt — imposed an economic and transport blockade on Qatar over its close ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. They demanded that Qatar sever these connections, shut down Al Jazeera, and break off diplomatic relations with Iran.

Doha responded by moving even closer to Tehran, and the boycott failed to achieve its aims. In January 2021, shortly before Joe Biden’s inauguration, it was lifted.

Now, as Trump conducts negotiations with Iran, unity in the Arab world appears to be a priority for the new administration in Washington. In the event of an armed conflict with Tehran, the U.S. would need to maintain a united front with the Gulf monarchies.

Notably, according to Trump, it was the Qatari leadership that convinced him not to “do a vicious blow to Iran, ” and Qatar’s role as a mediator between Iran, the Arab world, and the U.S. is poised to grow even more prominent in the near future. Much will hinge on the outcome of negotiations between Washington and Tehran currently underway in Oman. Despite four rounds of consultations, the talks have yet to produce tangible results.

For the Trump administration, which is seeking to bring long-awaited peace to the Middle East, Qatar is also a crucial intermediary in its efforts to broker a deal between Israel and Hamas. At present, talks between the Jewish state and Palestinian militants are being held in Doha.

Economic interests further strengthen the bond between Trump and Qatar’s ruling family. Shortly before the president’s trip to the region, the Trump Organization — now led by his sons — secured a $3 billion deal to build a luxury golf club in Qatar.

Following Trump’s visit, the White House announced that Washington and Doha had signed agreements worth at least $1.2 trillion. Among them was a major deal for Qatar Airways to purchase 210 aircraft from U.S. aerospace giant Boeing.

Crowning the visit was a $400 million Boeing 747 gifted to Trump by Qatar. Dubbed the “flying palace,” it is set to become a symbol of the deepening ties between Doha and Washington — or, at least, between the royal family and the Trump family.