Trump administration officials could be prosecuted for violating a ban on deporting migrants to El Salvador, Chief Judge James Boasberg said on Apr. 17. Meanwhile, Nayib Bukele, the eccentric president of the small Central American country has, promised Trump to take in deportees from the U.S. and house them in his prisons — for a fee. The first group sent there under the new program consisted of more than 250 Venezuelans. Under Bukele, El Salvador already ranks first globally in per capita incarceration. Now it turns out that random people are ending up in migrant prisons alongside real criminals.

Content

Welcome to El Salvador

How Tren de Aragua became a transnational crime syndicate

A tattoo is enough to get you in prison

Mega-prison for mega-gangs

Who is Mr Bukele?

Welcome to El Salvador

In March, Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele posted two videos on social media that showed military and police officers dragging shackled men out of airplanes. The prisoners are forced to run down the airstrip to buses that take them to El Salvador's largest and most heavily guarded prison, CECOT (Terrorism Confinement Center). “On your knees!” the guards command. The kneeling, shackled men are shaven bald. The migrants, dressed in white prison uniforms, are corralled into a huge common cell with metal three-tier bunks. The door slams shut. “They are all confirmed murderers and particularly dangerous criminals, including six rapists of minors,” Bukele explained in his caption under the Mar. 30 video.

The 278 detainees are Venezuelan migrants deported by U.S. authorities on Mar. 16 (261 people) and Mar. 30 (17). “These are the monsters sent into our Country by Crooked Joe Biden and the Radical Left Democrats. How dare they! Thank you to El Salvador and, in particular, President Bukele, for your understanding of this horrible situation, which was allowed to happen to the United States because of incompetent Democrat leadership,” Trump wrote, reposting the Mar. 16 video. During his election campaign, the Republican candidate insisted time and again that thousands of dangerous criminals were among the migrants who had entered the country under President Biden and that only their mass deportation could save the U.S. from criminal chaos.

U.S. authorities believe the deportees to be members of Tren de Aragua, one of the most dangerous criminal groups in the Western Hemisphere, recognized as a terrorist organization in the U.S. But has the deportees' involvement actually been proven?

How Tren de Aragua became a transnational crime syndicate

Tren de Aragua originated in the early 2010s in a prison in the Venezuelan state of Aragua. A group of inmates formed a gang to extort money from other prisoners, and its influence grew dramatically after the advent of a powerful leader: murderer, drug dealer, and thief Héctor Guerrero Flores, known as Niño Guerrero. Tren de Aragua has been further strengthened “thanks to the unofficial policy of the Venezuelan government, which has delegated power in the most uncontrolled and violent prisons to gang leaders,” explains a report by InSite Crime, a foundation that brings together experts studying organized crime in Latin America.

Officials in the government of Hugo Chavez — who ruled the country from 2002-2013 — allowed Niño Guerrero to take full control of the prison where he was serving time, and the gang leader turned the facility into the headquarters of Tren de Aragua. By 2018, the megagang had spread its influence throughout Venezuela while also taking root in Colombia, Peru, and Chile. According to InSite Crime, Venezuelans were mainly involved in racketeering, kidnapping, drug trafficking, smuggling, theft, pandering, and cybercrime.

Venezuelan murderer, drug dealer, and thief Héctor Guerrero Flores, known as Niño Guerrero

Tren de Aragua soon went international. The severe drop in living standards resulting from Chavez’s rule led to the largest mass emigration in Venezuela's history. According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 7.7 million people — one Venezuelan in four — fled the country.

According to the UN, one in four people fled Venezuela under Maduro

Hundreds of criminals joined the outflux, while others facilitated it. During the pandemic, when the official border crossings between Venezuela and Colombia were permanently closed, Tren de Aragua set up an illegal migrant smuggling operation. They also took money for transportation and levied a “tax” from every hotel, hostel, and private house in the border area.

As InSite Crime explains, in the new territories, gang members eliminated possible competitors, bribed police and officials, and extorted money from local businesses. In Peru, Tren de Aragua is infamous for brutalizing prostitutes who refused to share their earnings with Venezuelan criminals. To crush the women's resistance, gang members videotaped the murders of sex workers and distributed them in chat rooms.

The members of the “megagang” — with an estimated headcount of 4,000-7,000 people — coordinated all moves with their ringleader, who until Sep. 20, 2023 operated out of a prison in the state of Aragua. On that day, the Venezuelan government planned to conduct a demonstrative sweep of the facility, but the 11,000 security forces troops were confronted by 5,500 prisoners, many of whom were armed. The 40-year-old leader of Tren de Aragua managed to escape through an underground tunnel before the operation even began. U.S. authorities are offering $5 million for information that could lead to his arrest.

After the prison was cleaned up, the authorities organized a press tour. Journalists touring the prison grounds could see swimming pools, a water park, a bar, several restaurants, chalets, and a network of underground tunnels.

Tren de Aragua members came to the U.S. the same way they came to other countries — mixed in with the influx of refugees. According to the latest U.S. Census Bureau data, there are more than 900,000 Venezuelan nationals living in the country, and since 2018, Venezuelans have made up the majority of asylum seekers.

Police reports in recent years show that Venezuelans allegedly linked to Tren de Aragua have been arrested in Colorado, Texas, New York, Illinois, Illinois, Florida, Louisiana, Indiana, Georgia, Virginia, and New Jersey. In June 2024, the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control placed the Venezuelan gang on a list of criminal international organizations that pose a threat to the entire Western Hemisphere. Then, on Feb. 20, Washington declared six Mexican drug cartels, the Salvadoran criminal group Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), and Tren de Aragua “foreign terrorist organizations.”

A tattoo is enough to get you in prison

And yet, U.S. authorities failed to present any serious evidence that the Venezuelans they have deported are linked to Tren de Aragua. After the deportations, CBS News journalists and human rights activists found that 75% of the Venezuelan migrants sent to the Salvadoran prison had no criminal records. The vast majority of those who did have previous convictions had committed non-violent crimes — mostly theft. The Department of Homeland Security told CBS News that the deported migrants “are actually terrorists, human rights abusers, gangsters, and more. They just don't have a rap sheet in the U.S.”

75% of Venezuelans deported to the Salvadoran prison have no U.S. criminal records

According to journalists, many migrants were accused of having ties to Tren de Aragua based on tattoos and social media postings. The Texas Department of Public Safety, for one, has published an illustrated list of tattoos that supposedly indicate membership in the megagang: a star on the shoulder, crowns, machine guns, grenades, dice, roses, tigers, jaguars, and a silhouette of basketball player Michael Jordan scoring a basket, to name a few. Tattooed phrases like “Hijos de Dios” (“Sons of God” ) and “Real Hasta la Muerte” (“Real till death”) were also grounds for legal action.

One of the oldest human rights NGOs in the U.S., the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), submitted a report on Mar. 28 on the “points-based system” used by U.S. authorities to charge Venezuelan detainees with having ties to Tren de Aragua and of involvement in terrorism. A migrant needs only to score eight points out of a possible 87 to be deported. According to the criteria, a migrant can “earn” as many as 14 points simply if U.S. police officers consider that their manner of dress, tattoos, gestures, or graffiti indicate their affiliation with Tren de Aragua.

After the first deportation, the White House said that of the 238 Venezuelans sent out of the country, 137 were deported under the 1798 Alien Enemies Act and 101 were deported under regular immigration law — that is, for being in the U.S. illegally.

On Mar. 31, the U.S. government officially acknowledged that Salvadoran migrant Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia, 29, had accidentally been sent to CECOT due to an “administrative error.” Abrego Garcia was deported in violation of a 2019 court order that prohibited deporting him from the U.S. to his home country due to the risk of his being targeted by local criminals. He was suspected of having ties to Salvadoran criminal groups, but the court exonerated him. Washington recognized that his deportation was a mistake — but despite the decision of the Supreme Court, it has no intention to return the Salvadoran to the U.S., where he has a wife and five-year-old son (both of whom are American citizens).

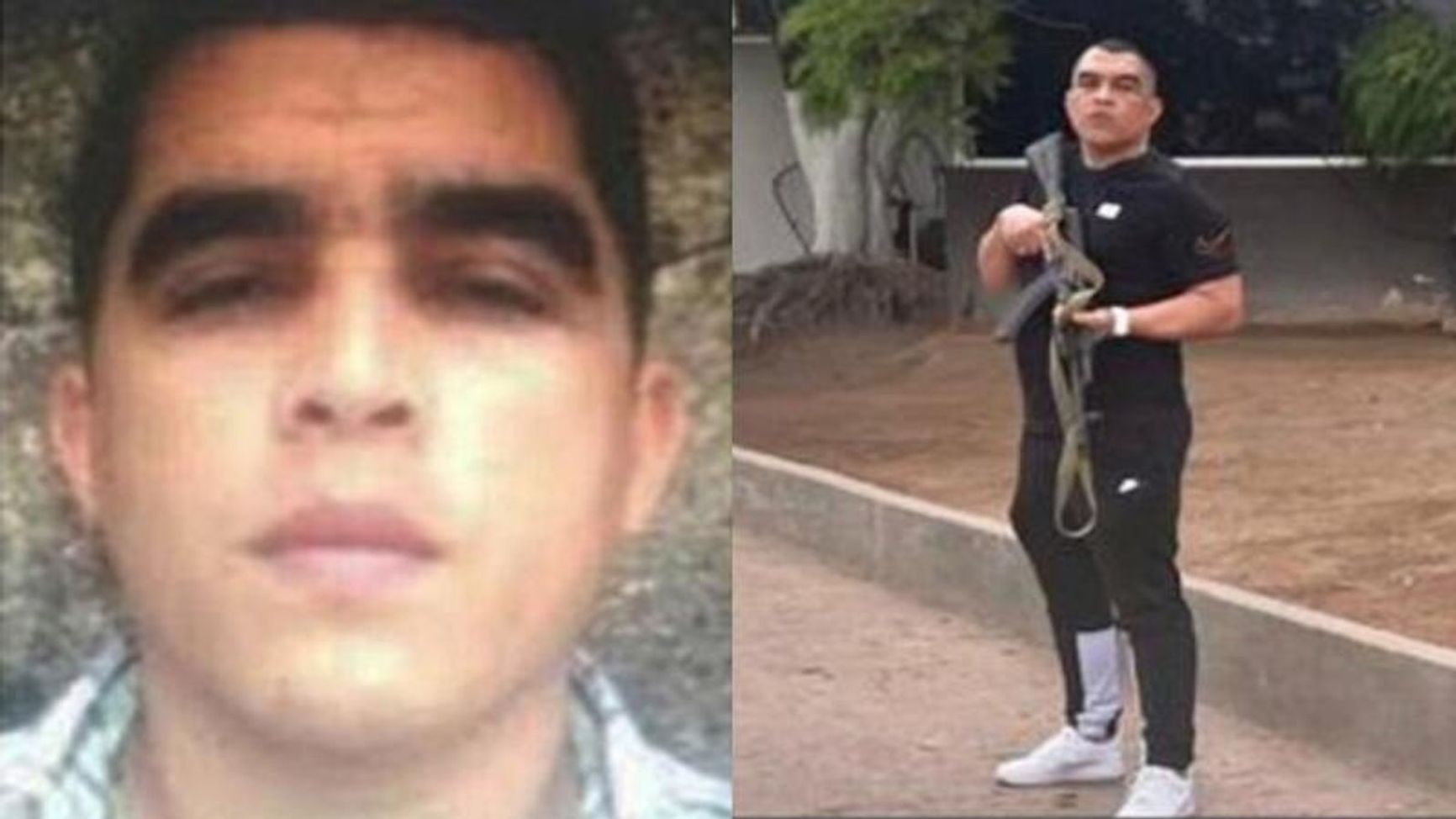

TIME Magazine photographer Philip Holsinger was present during the arrival of deported migrants to CECOT. He said he noticed one of the men crying as he was being shaved. “He was being slapped every time he would speak up…he started praying and calling out, literally crying for his mother,” Holsinger told reporters. The Venezuelan kept saying he was gay and a makeup artist, not a gang member. In the photo taken by Holsinger, family and friends were horrified to recognize 31-year-old Andry Hernandez Romero. The Venezuelan had indeed worked in his home country and in Colombia as a makeup artist and has never been in trouble with the law.

On Aug. 29, 2024, Hernandez Romero crossed the Mexico-U.S. border after receiving an invitation on the official U.S. CBP One app and applied for LGBT refugee status. The Venezuelan was immediately apprehended. The immigration authorities were suspicious about the two crowns with his parents' names tattooed on his wrists. Andry spent seven months in a migration prison in Texas before being deported to El Salvador. His relatives fear for his life.

A Venezuelan makeup artist was deported for a tattoo of two crowns with his parents' names

The Venezuelan government, in turn, went to the UN and hired a team of lawyers in El Salvador who petitioned the country's Supreme Court for the release of Venezuelans from the Terrorism Confinement Center. The hired attorneys describe the situation as “legal limbo”: “These cases have no precedent. There has never been a situation like this in the history of our country. There is no agreement or legal framework to protect these people.” In Venezuela, relatives of migrants trapped in CECOT have come out in protest, demanding the return of the prisoners to their homeland.

On Apr. 20, Bukele promised to hand over all Venezuelan detainees to Caracas with one condition: that the Maduro government would release the same number of political prisoners. According to human rights activists, Venezuela now has 890 such prisoners — opposition activists, journalists, and anti-government protesters. Caracas rejected the offer out of hand.

Mega-prison for mega-gangs

The shackled Venezuelans were escorted to a prison that is notorious for its harsh conditions. President Bukele, whom Trump calls a friend, rents out cells to U.S. authorities at a rate of $20,000 per inmate per year. Bukele could use the cash, given that he himself has claimed that El Salvador spends $200 million on its prisons annually.

CECOT is not just any prison — it is President Bukele's brainchild and a source of pride (to him). Opened in 2023, the Terrorism Confinement Center is officially Latin America's largest penitentiary facility. Located 74 kilometers from San Salvador, it can accommodate 40,000 inmates. Currently, CECOT is running at nearly 45% occupancy, meaning somewhere around 22,000 cots remain vacant.

The “mega-prison,” as the media call it, covers an area the size of six soccer fields. CECOT is separated from the outside world by a 40-foot wall built so that it will not collapse even if a booby-trapped car crashes into it at full speed. It has eight pavilions separated from one another by internal fences, and it boasts 19 guard towers. All fences and walls are electrified.

Security is provided by specially trained police and military personnel who work in week-long shifts. These features were revealed in an official 30-minute video showing President Bukele's visit to the “mega-prison.”

The Terrorism Confinement Center in El Salvador is the largest prison in Latin America

CECOT only holds convicts sentenced to life terms. They are prohibited from having personal belongings, making phone calls, and receiving any visits — whether from relatives or attorneys. As for books, only the Bible is allowed. Seventy-five prisoners can be housed in each cell, sleeping on three-tier metal bunks that do not feature mattresses, pillows, or bedding. They eat, wash, and use the bathroom inside the cell. The lights never go out. Instead of a ceiling, the cells have bars with an armed guard on top 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Inmates never leave the pavilion. There are no walks outdoors.

Bukele has publicly promised that he will not let these prisoners see sunlight until the day he dies. The only opportunity to leave the cells is the daily 20-minute walk in the spacious corridor, where inmates can stretch and exercise. Prisoners whose trials are ongoing participate remotely from specially equipped rooms.

CECOT holds thousands of members of so-called maras — the most dangerous Salvadoran gangs in the Western Hemisphere. The most numerous and threatening of these are the Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, and the Barrio-18.

Who is Mr Bukele?

Bukele became famous for defeating criminal gangs in El Salvador — a feat that required putting more than 2.5% of the country's adult population behind bars. Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 emerged in the 1980s in California, which became home to thousands of Salvadoran migrants fleeing the civil war (1979-1992) in their homeland. At first, all they wanted was to counter the already existing street gangs of African Americans, Mexicans, and Koreans, but they ended up outdoing all their rivals in brutality — using machetes and axes in their attacks.

El Salvador's president is famous for sending more than 2.5% of the country's adult population to jail

Maras members emerged from American prisons even more ruthless and united. Seeking to lower crime rates in the early 1990s, U.S. authorities expelled around 46,000 migrants, including dangerous criminals, to several Central American countries — primarily El Salvador.

In their homeland, the maras found themselves in an environment offering an ideal mix of poverty and lawlessness. Over the years, they essentially became a parallel government there. Ubiquitous racketeering, kidnapping, and murder became an everyday reality, as did gang warfare. The maras were ruthless and corrupted government officials with ease. With a population of just 6.5 million, El Salvador consistently ranked among the world's most dangerous countries.

In the bloody year of 2015, the murder rate reached 103 intentional homicides per 100,000 residents (in the U.S. the rate stands at 7.5). In 2019, 30 murders a day were business as usual for El Salvador. A string of governments tried to remedy the situation, either by force or through negotiations with the leaders of the maras, but things only deteriorated with each passing year.

The maras effectively controlled the country until 2019, when 38-year-old Nayib Bukele, the youngest president in El Salvador’s history, came to power. During his five years in office, the murder rate dropped to an official 1.9 murders for every 100,000 residents. InSite Crime experts suspect that the Salvadoran authorities slightly overstate their progress, but either way, one of the world's most dangerous countries has turned into one of the safest in the Western Hemisphere. How did Bukele accomplish that?

Nayib Bukele

By 2025, El Salvador had become the absolute world leader in per capita incarceration rate, with 1,824 inmates per 100,000 inhabitants. Experts from the Institute for Human Rights at the José Simeón Cañas Central American University estimate that El Salvador has imprisoned 2.6% of the country's adult population, mostly young men.

The new Criminal Code allows for trying minors starting from the age of 12 if they are charged with participation in criminal groups. The maximum penalty for those under the age of 16 is 10 years' imprisonment. Teenagers between the ages of 16 and 18 can be jailed for up to 20 years.

To defeat the maras, Bukele declared a state of emergency in El Salvador in March 2022. It abrogates the arrestee's right to be informed of the reasons for detention and the right to be provided with a lawyer. It also suspends the ban on detention for more than 72 hours without a court order.

Essentially, for more than three years now, law enforcement officials in El Salvador have been able to arrest and keep anyone behind bars for as long as they want based on nothing more than a suspicion or an anonymous call. The state of emergency remains in effect to the present day. More than 83,000 people have been arrested during that time.

Amnesty International, in its 2024 year-end periodic review, reports that in El Salvador there is “a widespread pattern of state abuse that includes thousands of arbitrary arrests, the adoption of a policy of torture in detention centers, and hundreds of deaths in state custody.” According to the latest figures, more than 330 detainees have died.

Human rights defenders report that police officers make arrests in order to meet daily quotas, they write about appalling conditions in overcrowded prisons, and they have documented dozens of cases in which arrests were made without any grounds or preliminary investigation. Experts are unanimous: while Bukele has succeeded in weakening, if not eliminating, the maras, no one can guess how many innocents are behind bars — potentially for decades.

“A widespread pattern of state abuse that includes thousands of arbitrary arrests, torture in detention centers, and hundreds of deaths in state custody,” Amnesty International writes about El Salvador

The leaders of Argentina, Ecuador, Honduras, and Paraguay are consistent in their support for Bukele's methods of fighting organized crime. By receiving migrants deported from the U.S., El Salvador's president, who was re-elected in 2024 for a second term despite an explicit constitutional ban, has received from Washington both money and a long-awaited endorsement of his regime from the nominal leader of the free world.

U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem visited El Salvador in March. In front of a CECOT prisoner cell, she recorded an address: “I want everybody to know, if you come to our country illegally, this is one of the consequences you could face. If you do not leave, we will hunt you down, arrest you, and you could end up in this El Salvadorian prison.”

Meeting with Bukele at the White House, Trump called his Central American counterpart a friend. It was as though the two leaders were looking in the mirror. “They say that we imprisoned thousands, but I like to say that we actually liberated millions,” Bukele said, referring to the drop in crime rates at home. Trump’s response: “Who gave him that line? Do you think I can use that?”