The 1,000-day threshold in the Russian-Ukrainian war was marked by several events that increased the likelihood of nuclear war. For the first time, Ukraine used Western ATACMS and Storm Shadow missiles to hit targets on Russia's internationally recognized territory. The Kremlin responded by unveiling an updated nuclear doctrine featuring lowered requirements for the use of nuclear weapons — and for the first time, it attacked Ukraine using an intercontinental ballistic missile (or its medium-range counterpart) capable of carrying a special warhead. The Insider explains what nuclear war and its aftermath could look like, as well as how and where to escape it — before it’s too late.

Content

What kinds of nuclear weapons are there?

Who has nuclear weapons?

Why does the world need nuclear weapons?

How many times have nuclear weapons been used?

Who can decide to launch a nuclear strike and how do they go about it?

What makes nuclear war so dangerous?

Will there be a “nuclear winter”?

Where will the missiles go?

How great is the threat of nuclear war?

What should you do in the event of a nuclear explosion near you?

What kinds of nuclear weapons are there?

'Nuclear weapons' is an umbrella term for explosive devices that employ the fusion or fission of atomic nuclei to generate energy for the blast. Weapons referred to as 'nuclear' use the energy generated by the fission of heavy nuclei, such as uranium-235 and plutonium-239. Thermonuclear weapons (often referred to as “the hydrogen bomb”) are based on the fusion of light nuclei — the hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium.

Nuclear weapons have enormous destructive power, usually measured in kilotons and megatons of TNT equivalent — that is, in thousands and millions of metric tons of explosives. To compare, the Russian Kh-101 cruise missile that hit the Ohmatdyt Children's Hospital in Kyiv this past July carries a warhead of only 400 kilograms.

A nuclear strike has a solid kill zone spanning dozens of kilometers. If dropped on a densely populated area, a nuclear bomb could claim millions of lives and irrevocably destroy all infrastructure.

A nuclear strike has a solid kill zone spanning dozens of kilometers

Nuclear powers possess intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, aerial nuclear bombs, and tactical nuclear warheads (delivered by cruise missiles, artillery shells, and low-yield aerial bombs).

Strategic nuclear forces combine three components: land-based (missile forces), naval (nuclear-powered submarines with ballistic missiles), and airborne (strategic bombers). All three components together are referred to as the nuclear triad.

Who has nuclear weapons?

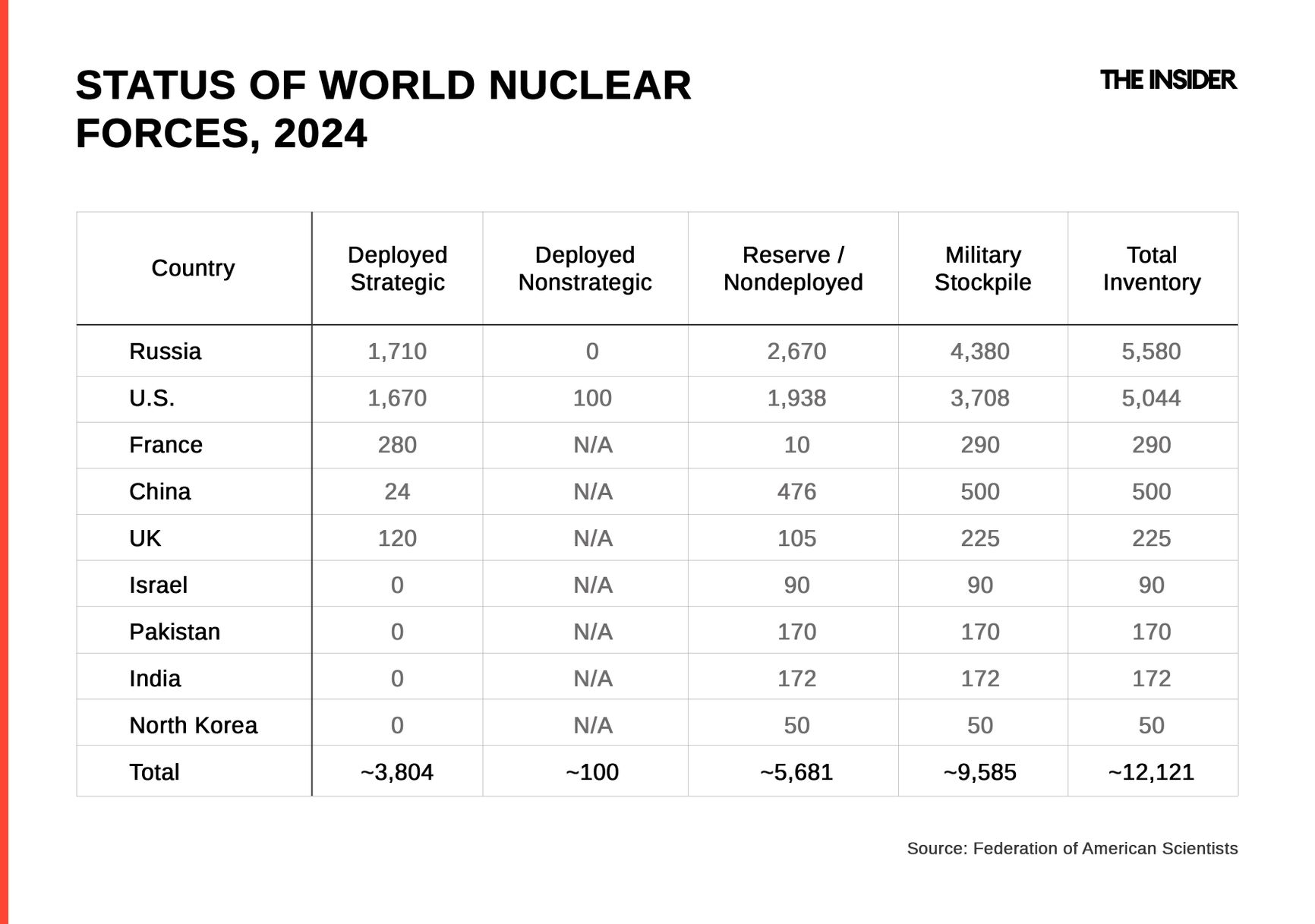

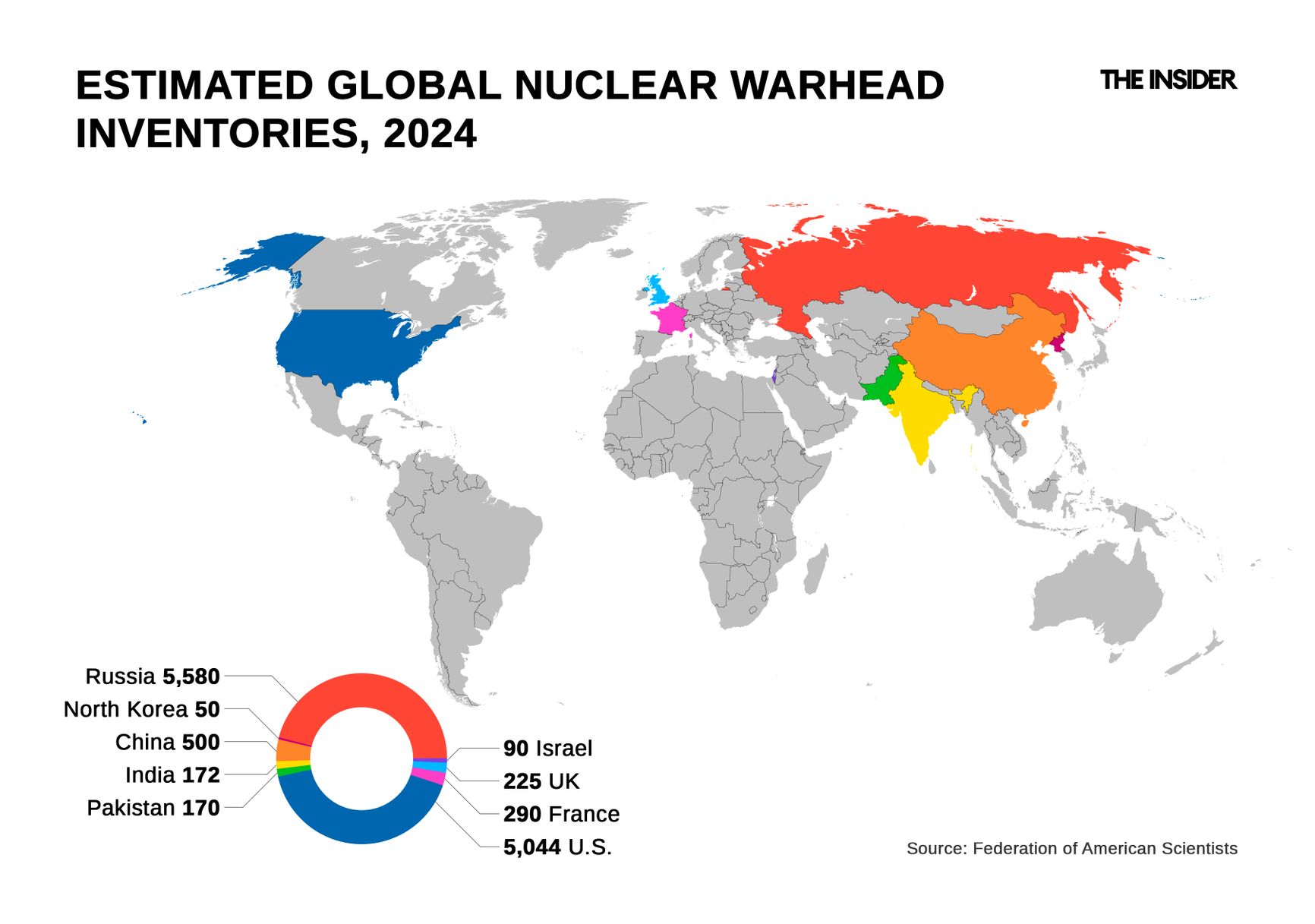

Nine countries in the world possess a total of 12,121 nuclear warheads, with only 3,804 deployed. All permanent members of the UN Security Council — Russia, the United States, China, the UK, and France — have deployed strategic nuclear warheads. The U.S. and Russia hold 88% of the weapons. A nuclear triad is possessed by the United States, Russia, and, presumably, China.

Several countries once had nuclear arsenals but gave them up. Among them are apartheid-era South Africa (whose weapons were eliminated before the democratization and transfer of power to the black majority in the early 1990s), and also Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan (each of which received a share of the Soviet nuclear arsenal after the collapse of the USSR, but then either destroyed the warheads or transferred them to Russia with the assistance of international mediators, primarily the United States).

Several countries, including Ukraine, used to possess nuclear weapons but have given them up

For more information on why modern Ukraine cannot and will not resume its nuclear program, see “Existential Lies. How Putin invented a nuclear threat from Ukraine to justify war.”

Why does the world need nuclear weapons?

Since the American nuclear strikes on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, nuclear weapons are believed to have played a deterrent role in international relations, preventing a direct military clash between members of the nuclear club and thus foreclosing the possibility of a new world war. In the bipolar world of the Cold War era, the concept of deterrence defined relations between the two superpowers: the Soviet Union and the United States. Deterrence is based on the notions of mutual assured destruction (MAD) and nuclear parity: the approximate equality of nuclear potentials and the inevitable response in the event of a first strike make the conflict pointless (at least in theory), since both sides would simply end up destroying each other.

Nuclear parity is generally maintained today: Russia and the United States possess almost the same number of deployed nuclear warheads for strategic carriers, although when it comes to tactical-class warheads, the Russian stockpile is much larger. In addition, the architecture of existing air and missile defense areas in Russia and the United States is believed to provide sufficient protection for political decision-making centers — and for the nuclear-tipped missile launch positions under their command — to respond in the event of an attack. In other words, in the event of a nuclear war, both countries would have ample time and opportunity to use their entire arsenal to retaliate.

One has to admit, however, that nuclear weapons have not made the planet a safe place: during the Cold War, the confrontation between the superpowers took other forms, with numerous localized proxy conflicts breaking out in remote regions. Furthermore, today the concept of deterrence does nothing to thwart new threats like cyberattacks or disinformation campaigns.

How many times have nuclear weapons been used?

Combat use of nuclear weapons, as we know, occurred only twice: on Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945, when American forces dropped nuclear bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

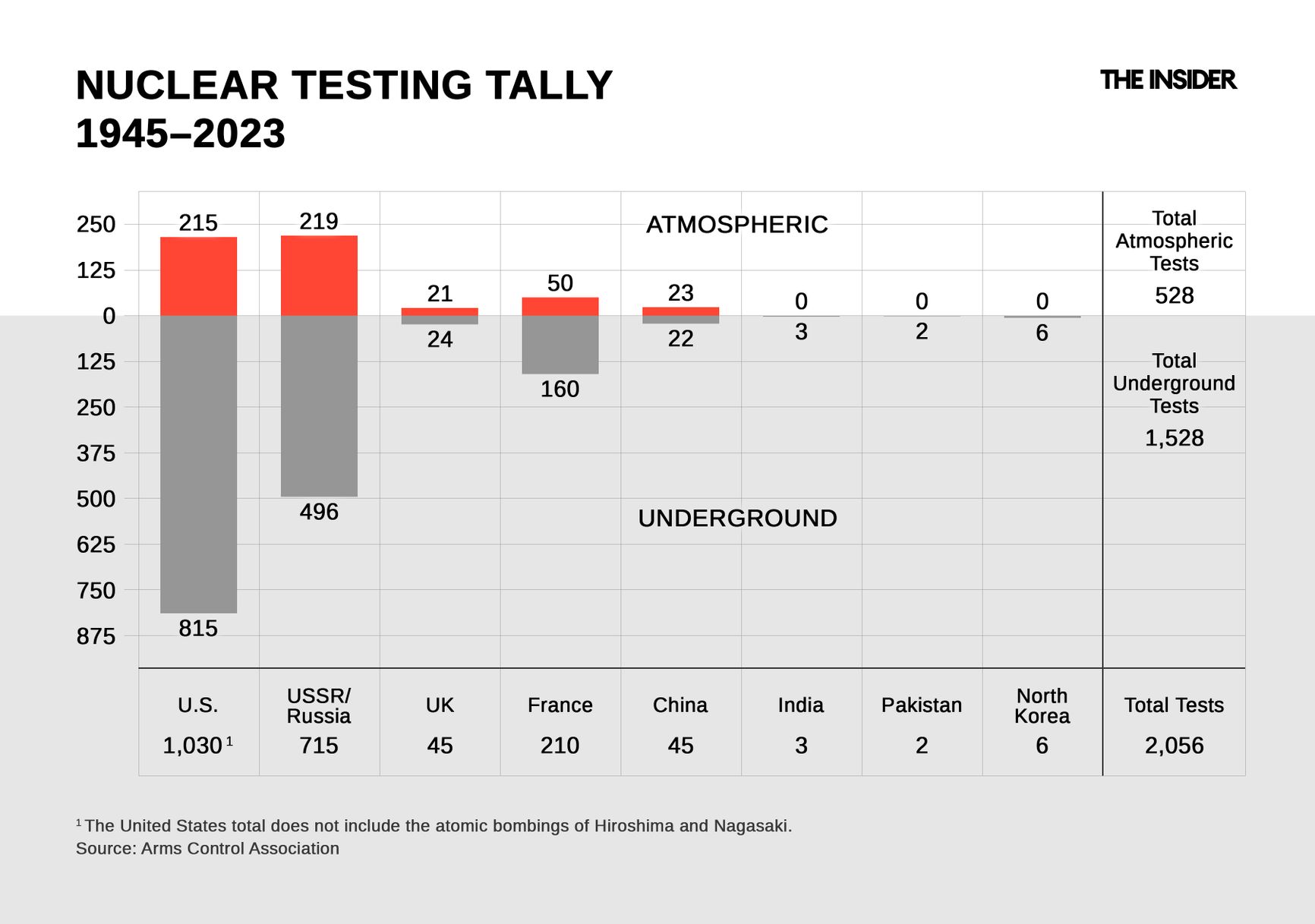

As for test explosions, there have been more than 2,000 since Jul. 16, 1945: 1,030 of them were conducted by the United States and 715 by the Soviet Union. In the 21st century, North Korea remains the only country conducting nuclear tests.

The most powerful thermonuclear explosion — 58.6 megatons — was registered during the test of the AN 602 Tsar Bomba in 1961 on the Novaya Zemlya archipelago. The flash was visible at a distance of 1,000 kilometers, and the resulting mushroom cloud rose to a height of 67.3 kilometers — visible from 800 kilometers. The seismic wave caused by the blast circled the globe three times. Buildings in a village on Dikson Island, 780 kilometers away from the test site, had their windows blown out.

Who can decide to launch a nuclear strike and how do they go about it?

The procedure for using nuclear weapons varies from country to country. In the UK, the Prime Minister gives the order, but if the military commanders are unsure about carrying it out, they can appeal directly to the commander-in-chief — the ruling monarch.

In France and the U.S., the relevant powers are in the hands of the presidents. In Pakistan and India, strikes can be launched by special collective bodies.

In China, the decision to launch a nuclear strike falls under the purview of the Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. Military personnel in command centers are supposed to receive two separate orders: from the Central Military Commission and from the country's Joint Staff Department.

In Russia, the decision is made by the president. According to various reports, a nuclear strike requires a chain-of-command order that involves five to seven people, from the president down to the operators on duty in command centers. The Minister of Defense and the Chief of the General Staff, who, like the President, have “nuclear briefcases” with launch codes, participate in the process, as do liaison officers. Launch is only possible if codes are entered on at least two of the three briefcases.

In Russia, the decision to use nuclear weapons is made by the president

The principles of nuclear weapons use are described in program documents of military planning, military doctrines, and national security strategies.

Russia's nuclear doctrine, officially referred to as “Basic Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation on Nuclear Deterrence,” was adopted on Nov. 19, 2024. It provides for five cases in which the use of nuclear weapons is permitted. Some of the scenarios do not involve a nuclear attack from an enemy state. These are:

(a) The receipt of reliable information about the launch of ballistic missiles attacking the territories of the Russian Federation and (or) its allies.

b) The use by the enemy of nuclear or other types of weapons of mass destruction against the territories of the Russian Federation and (or) its allies, against military formations and (or) facilities of the Russian Federation located outside its territory.

c) The enemy's impact on critical state or military facilities of the Russian Federation, the disabling of which would disrupt the response of nuclear forces.

d) Military aggression against the Russian Federation and (or) the Republic of Belarus as members of the Union State with the use of conventional weapons that creates a critical threat to their sovereignty and (or) territorial integrity.

e) The receipt of reliable information about the massive launch (take-off) of aerospace attack means (strategic and tactical aircraft, cruise missiles, unmanned, hypersonic, and other aircraft) and their crossing of the state border of the Russian Federation.

There are no reliable criteria for determining a “critical threat to sovereignty and territorial integrity” or the “massive” launch of enemy missiles or aircraft.

What makes nuclear war so dangerous?

The detonation of a nuclear warhead causes a powerful shock wave, light radiation, and direct ionizing radiation. It is also accompanied by a radioactive pulse and a powerful electromagnetic pulse that disables electronics.

An attack on cities with high-rise buildings would produce devastating fire tornadoes that would scorch even reinforced concrete and earth, not to mention human flesh.

A nuclear explosion would scorch even reinforced concrete and earth, not to mention human flesh

For example, a strike on Moscow with a 350-kiloton W78 thermonuclear warhead for the LGM-30G Minuteman III ICBM would have an impact radius bordering on 14 kilometers, would kill about 620,000 people, and injure almost 2.5 million.

Here you can create a simulation of a nuclear attack in different places on the planet.

For a long time, the most dangerous ramifications of the large-scale use of nuclear weapons were considered to be catastrophic climate effects known as “nuclear fall” and “nuclear winter.”

Will there be a “nuclear winter”?

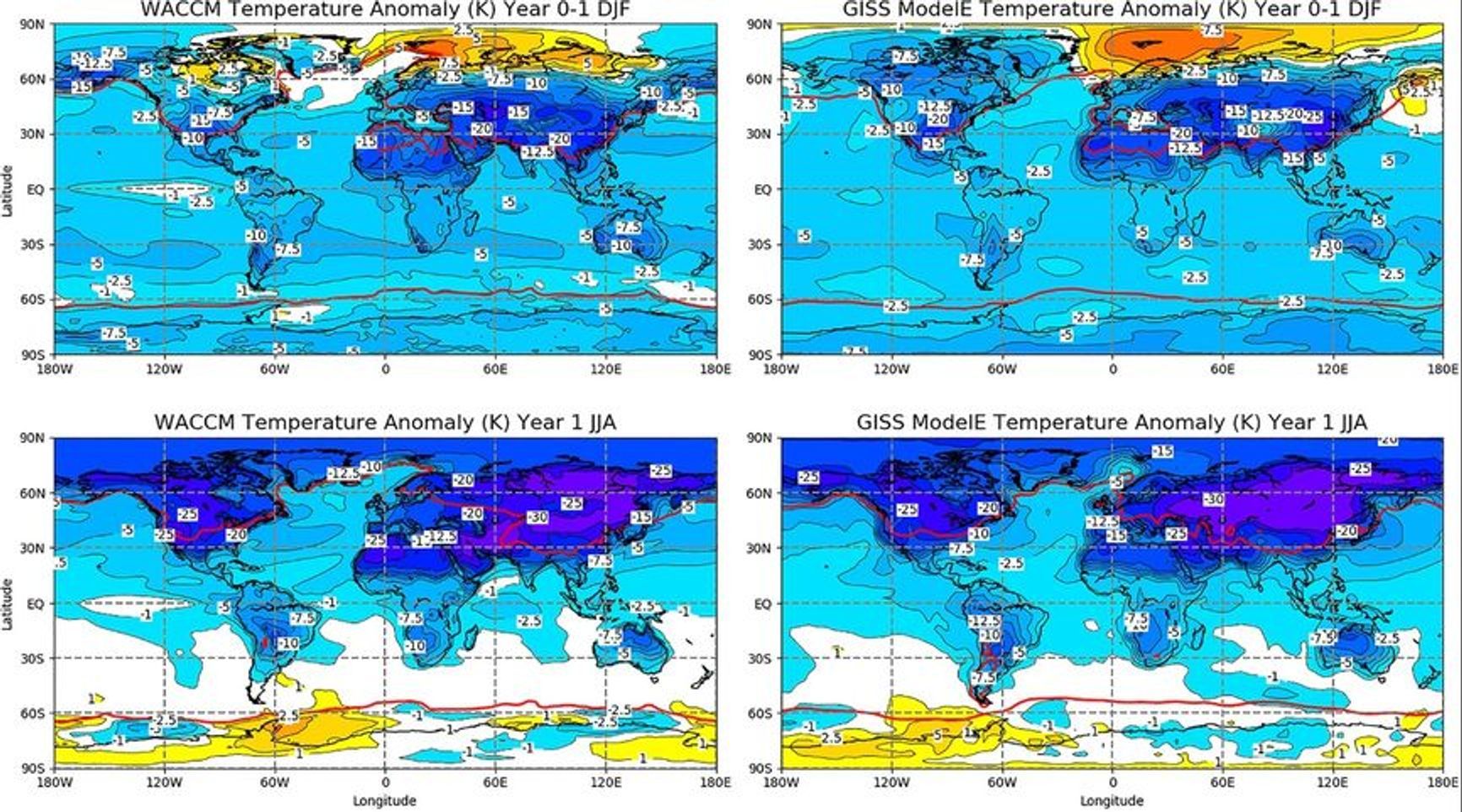

In the early 1980s, scientists concluded that even a limited nuclear conflict would release enough dust, smoke, and soot into the atmosphere to stop the sun's rays from reaching the Earth's surface for a long time. Temperatures will drop, and farming will become impossible.

Moderate scenarios spoke of a “nuclear fall”: a short-term 2-4 °C drop in temperature. The most pessimistic ones predicted a new ice age with the almost inevitable extinction of humanity.

However, the concept of a “nuclear winter” is now being challenged. The calculations of catastrophic cooling did not take into account many compensating factors — from the greenhouse effect to the reduced ability of soot-covered ice to reflect sunlight.

In addition, even a significant cooling after a hypothetical nuclear war would not wipe out all of humanity: part of the population would survive, eventually repopulating the planet.

Significant cooling after a hypothetical nuclear war would not lead to humanity's demise

A computer simulation of the consequences of a conflict between the United States and Russia showed that Moscow, St. Petersburg, Krasnodar, and Yekaterinburg would face a 20-25°C drop in average summer temperatures. Moscow's winters would become on average 10 degrees colder, and Krasnodar's 15 degrees colder. The minimal climate requirement for agriculture — a vegetation period of 50-75 days — would remain available only in Krasnodar Krai. In some regions, the amount of precipitation would decrease between four- and tenfold. Similar disasters would affect the entire Northern Hemisphere, resulting in global famine. The thinning of the ozone layer would expose the Earth's surface to increased levels of ultraviolet radiation, leading to a 40% surge in the incidence of skin cancer. The effect would last about 10 years — until the soot particles gradually settle down.

Where will the missiles go?

What would be the likely objects of interest in a nuclear conflict between Russia and the U.S.? Targets for nuclear weapons are classified, but in the case of the United States, operational plans are known to envision several attack scenarios that prioritize targets as follows: enemy infrastructure for weapons of mass destruction, military installations, military and political leadership, and auxiliary military infrastructure.

In the past, the Americans planned to target economic and industrial centers (a 1956 map with publicized targets is available here), and Russia, as far as we can tell, still keeps its nuclear weapons aimed at European and North American urban agglomerations.

Computer simulations usually use the premise of strikes on major cities and economic centers. Available simulations of an exchange of strikes between NATO member states and Russia suggest that at least 85 million people would be killed or injured in the first 45 minutes.

How great is the threat of nuclear war?

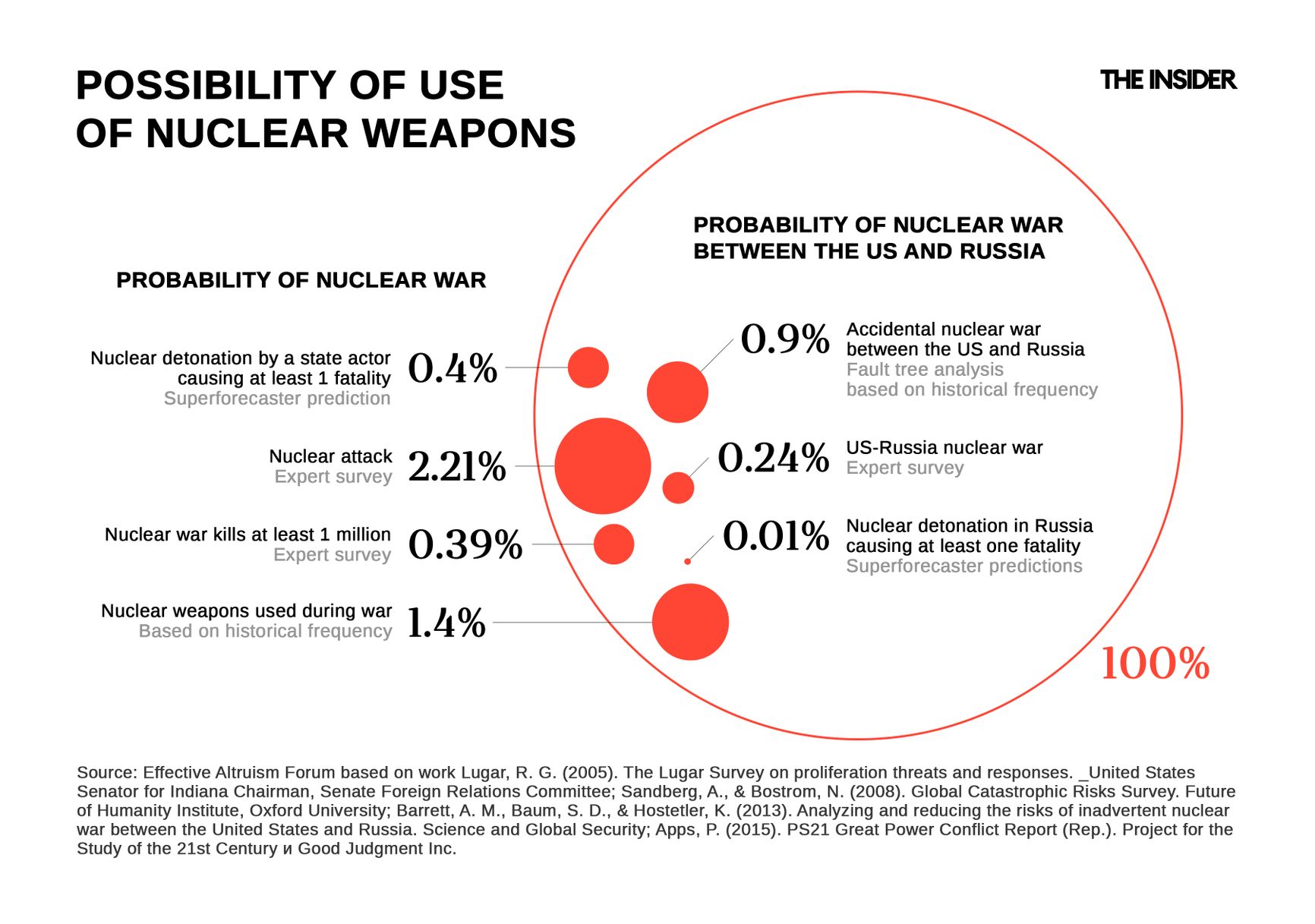

Scientific and expert estimates of the probability of the combat use of nuclear weapons give a maximum value of 2.21% in annual terms. The likelihood of a nuclear war with high casualties or a nuclear exchange between the U.S. and Russia is even lower. Nevertheless, for a child born now, the estimated probability of experiencing a nuclear catastrophe during their lifetime is quite high from a purely statistical standpoint — though scientists argue as to whether quantitative and qualitative methods apply to the problem of assessing the effectiveness of nuclear deterrence. In other words, these estimates are highly tentative and uninformative.

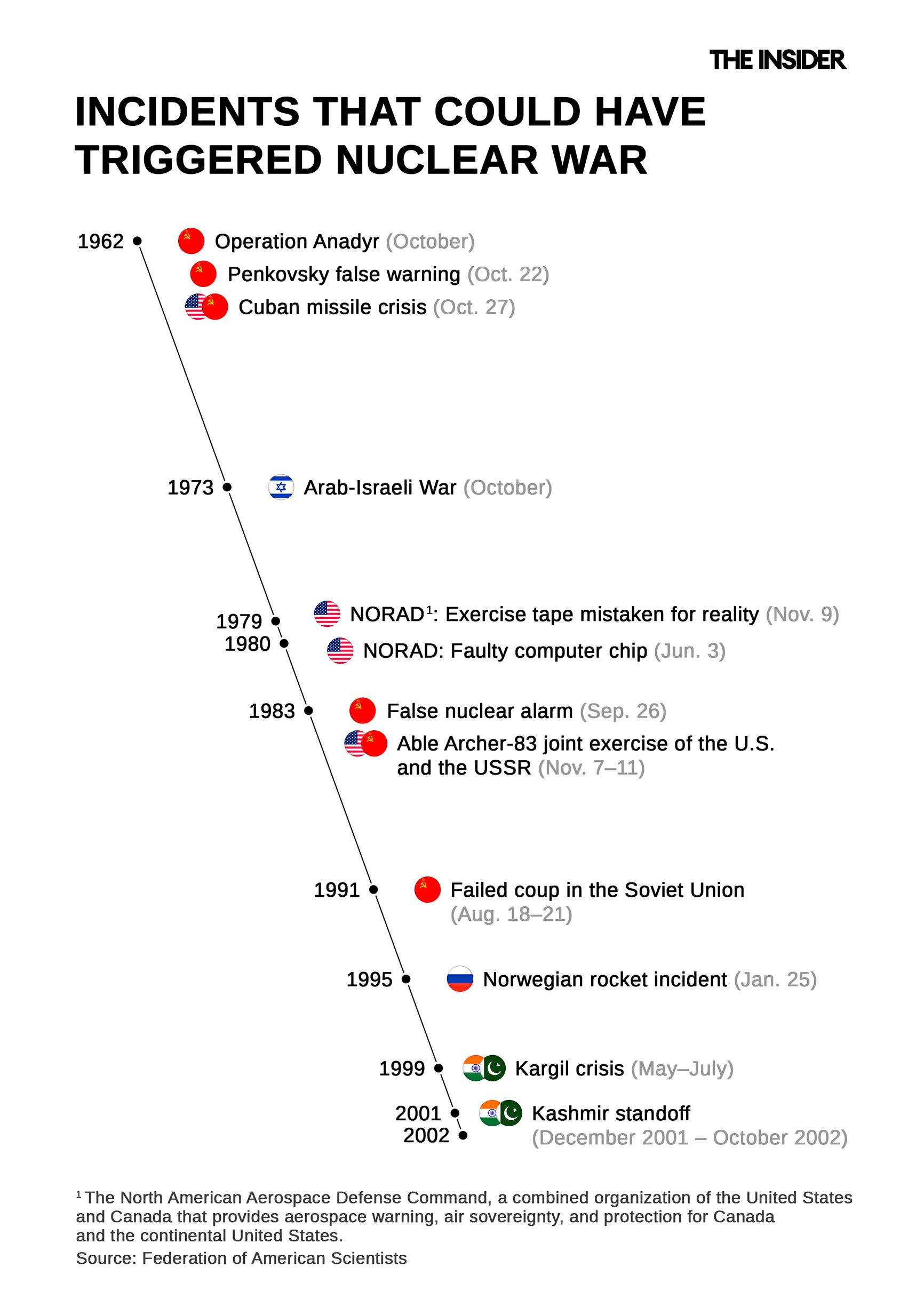

Since 1945, the world has been on the brink of nuclear war several times. The most dangerous incidents occurred in 1983, not during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

The main reassuring factor is the inexorable decline in the world's nuclear arsenal: from a peak of 70,374 warheads in 1986, it has been reduced to 12,121 today.

On Jan. 3, 2022, the five permanent member states of the UN Security Council that possess the largest nuclear arsenals issued a joint statement:

“We declare that in a nuclear war there would be no winners and it must never be fought. Given that the use of nuclear weapons would have far-reaching consequences, we reaffirm that these weapons — as long as they remain in existence — must serve defensive purposes, deter aggression, and prevent war.”

Less than two months later, Russian troops invaded Ukraine, and once his blitzkrieg failed, President Vladimir Putin began blackmailing Kyiv's Western allies with the threat of a nuclear strike.

Back in 2020, the famous Doomsday Clock — a symbolic countdown before the nuclear apocalypse — was moved to 23:58:20, or 100 seconds to midnight (the hands were left at the same mark in 2021 and 2022). In 2023, the hand was moved to 90 seconds to midnight, reflecting the highest risk of a global catastrophe since U.S. researchers from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists began counting in 1947.

Following Russia's full-scale attack on Ukraine, the authors of the project released an update to their assessment in which they reiterated that the possible escalation of a conventional conflict into nuclear war poses a major threat to world peace and security.

What should you do in the event of a nuclear explosion near you?

The best thing, of course, is to get as far away as possible from a place where nuclear explosions may occur. The best bets for finding a safe haven are Antarctica and Easter Island in the Pacific (1), South America and Australia (2), or Iceland and Canada (3). Russia is likely to be relatively safe in remote areas of Siberia.

Russia will likely be safest in remote areas of Siberia

If an explosion does occur nearby, you must take shelter in the basement of a concrete building. You will probably have at least 10 minutes to reach it before full exposure to nuclear fallout occurs. You will have to stay there for at least 24 hours, and then act based on the instructions of the relevant authorities. Most likely, after 48 hours, the radiation levels in your surrounding area will drop to acceptable levels.

Of course, it is a good idea to prepare a first aid kit, a set of essential items, and a supply of food and water. The list of things you need to survive the first few hours and days of a nuclear apocalypse varies, but it generally boils down to the following:

- Bottled water

- Foods with long shelf lives

- Batteries

- Flashlights or lamps

- A radio

- Basic medicines

- A set of tools

- Camping equipment

- IDs

- Sleeping bags

- Personal hygiene items

- Pen and paper

You can expand the list to cover your specific needs, or follow available guides — but we sincerely hope you never have to use any of these items for the purpose of living through the end of the world as we know it.