Exactly 50 years ago, Portugal's Carnation Revolution toppled a 48-year-old dictatorship — a tenure unprecedented by European standards — which had outlasted even that of the Franco tyranny in neighboring Spain. The fall of the regime was a foregone conclusion. An aging, sluggish empire, sinking deeper into isolation, embroiled in endless conflicts with its former colonies, fell at the hands of its own military, tired of a protracted and futile war. Portugal is meeting this milestone amid a shifting political landscape, with the center-right winning recent elections and the far-right gaining strength.

Content

Unravelling through war

The bloodless coup

The “revolutionary process”

A European democracy

The import-export of corruption

See if this sounds familiar: an aging, out of touch, increasingly isolated empire mired in an endless conflict against the people they once colonized is brought down by its own armed forces, fed up with the prospect of fighting an endless, unwinnable war. This is how, 50 years ago today, Portugal’s 48-year-long dictatorship — the longest in Western Europe — was brought down: a coup by low and mid-level army officers not seriously opposed by any forces actually willing to fight for the dictatorship. A military revolt immediately joined by the civilian population, and an amalgam of troops and civilians encircling the last holdout of the fallen dictator, who for his own physical safety needs to be brought out in the belly of an armoured. Portugal’s Carnation Revolution is a testament to how, sometimes, even the most seemingly entrenched power can unravel in a single breath. All empires, in the end, are mere illusions of force.

In fact, the most apt question might be: why did it take so long? Even at its peak, the old regime was nothing to rave about. A stale, corporatist system, the “Estado Novo” (or New State), as it was called, was a politically organized oligarchy that borrowed many of its attributes from fascist regimes like Mussolini’s Italy, including an organization for the indoctrination of youth and an all-encompassing single party. Established in the early 1930s after a period of military dictatorship that had started in 1926, the Estado Novo was mostly a parochial power, in which economic competition was limited by the State to protect established industries that typically remained in the hands of a few privileged families. The extraction and trade of natural resources in the colonies were also monopolies gifted to the few oligarchs who were given free economic reign in exchange for their political support to the system that so handsomely rewarded them.

Little trickled down to the people — neither in the African territories, nor even back home. Until well into the second half of the 20th century, Portugal was essentially a feudal country. The epitome of this political and economic pact of exploitation was the weekly appointment the dictator António Oliveira Salazar had with the preeminent banker of the day, Ricardo Espírito Santo Silva. These two men would organize national politics at their tea meetings every Sunday at Guincho beach, near Lisbon, deciding who got to do business and who didn’t, what investments would get done, who prospered and who failed.

Little trickled down to the people in Salazar's Portugal — neither in the African territories, nor even back home

Unlike more violent contemporary European dictators, Salazar doled out political repression notably intelligently. Not a military hardliner like his neighbour Franco in Spain, the Portuguese dictator was a law professor who gained prominence – and, ultimately, power – as the strict Finance Minister who brought the public accounts into order after years of political and financial turmoil. With a high-pitched voice and the style of a rural priest — he remained unmarried his entire life — Salazar cultivated a sort of reverse personally cult, portraying himself as a modest, frail workaholic, selflessly dedicated to keeping the Nation safe and quiet.

António de Oliveira Salazar at his desk

Photo: FOTOTECA/SNI/O SÉCULO/LUSA

Obviously, strict press censorship and a strong propaganda machine would cement his image as a hardworking public servant who wanted nothing for himself, instead of as the typical fascist strongman. In line with Salazar’s orderly, softer-looking form of totalitarianism, the state security apparatus worked more by suggestion than by actual overt violence. The political police, the PIDE, would manage a network of informants and enforce the will of the regime, sometimes brutally – especially with communist dissidents, the major force of political opposition, which survived clandestinely throughout the entire lifespan of the regime. By reducing visible violence and cloaking arbitrary power under a mask of legality, the Government was able to legitimize harsh punishment for dissent as being necessary for the safety of the country.

Salazar called it “to live habitually”: the Portuguese were expected to go about their business, in an orderly manner and without ambition, and the State would take care of everything else

To the people, violent repression was not an everyday fact of life, and the incentives were clear: stay in your lane, don’t get involved in politics, or else you will come to know the wrath of the State. Salazar called it “to live habitually”: the Portuguese were expected to go about their business, in an orderly manner and without ambition, and the State would take care of everything else. It wasn’t about making History. It was more about living outside of History — of simply keeping things as they were.

Unravelling through war

Before any regime entirely loses its grip on its people, it first loses its grip on reality. For the Portuguese Estado Novo, this started to happen in slow increments after World War II. Salazar had expertly maintained a position of clever neutrality during the war, simultaneously doing business with Nazi Germany and, especially after the US entered the war, allowing the Allies to use a key military base in the mid-Atlantic Azores islands. But at the end of the war, the dictator failed to realize that a Western victory with a decisive contribution by the United States meant the end of colonial empires. Salazar stubbornly held on to Portugal’s colonies, a patchwork of dispersed territories ranging from West Africa to Southeast Asia, the last remnants of what had been essentially a mercantile, not a territorial, empire.

Salazar stubbornly held on to Portugal’s colonies, a patchwork of dispersed territories ranging from West Africa to Southeast Asia

Even as war-winners like Britain and France started decolonizing, Portugal further isolated itself in the fiction that it existed as a “pluricontinental nation.” It all started unravelling in 1961, when independence movements broke out in Angola, later spreading to Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau. In December of that year, another blo came when the Indian Union invaded and took control of the few coastal cities that constituted Portugal’s remaining colonies in India. (Other territories in the subcontinent had already effectively been taken over by Indian militants in 1954.)

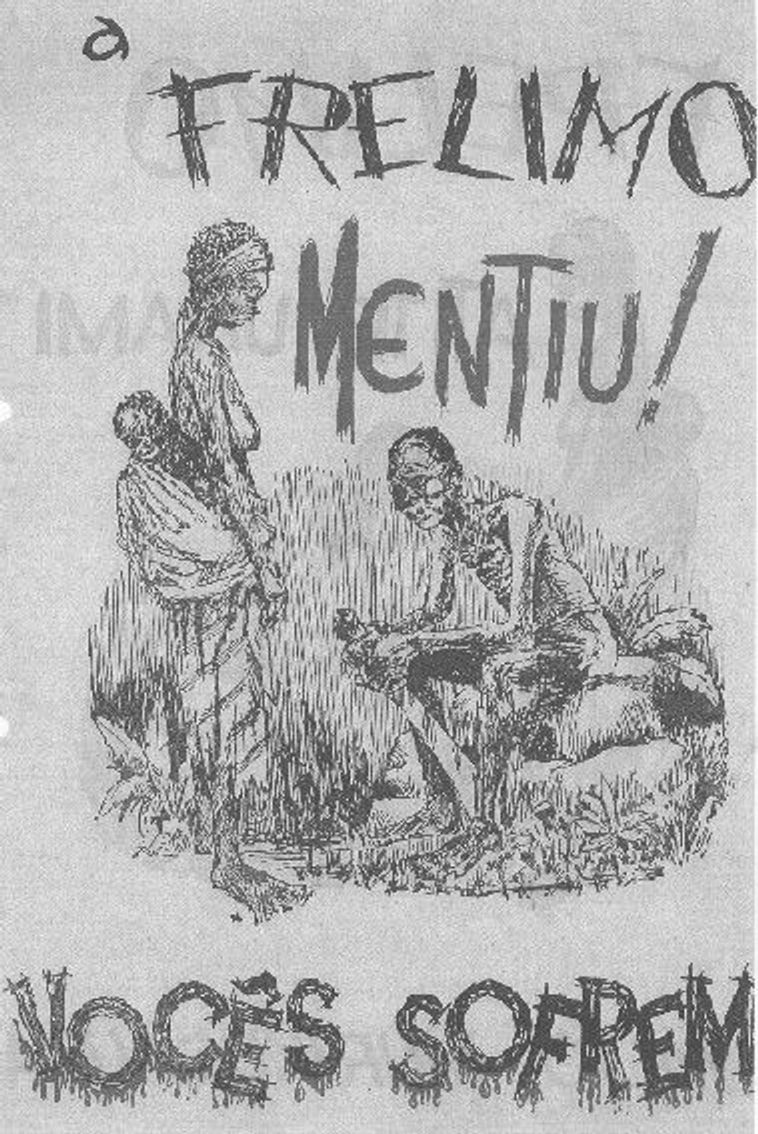

Portuguese propaganda thrown from airplanes during the Mozambican War of Independence (1967-1974) reading “FRELIMO lied! You suffer.”

The liberation movements and the loss of the so-called Portuguese State of India were more than military embarrassments. The regime’s whole claim to legitimacy was based on its preservation of the great Portuguese empire that dated back to the age of discovy. Without empire, what use was the dictatorship? The war to keep control of the colonies soon became the State’s entire “raison d’être.” “Angola is ours,” the slogans proclaimed. Resisting increasing pressure from the United Nations and whatever reluctant allies it still had, Portugal lost the thread of History. From every city and village in the country, young men were being enlisted to fight to preserve territories they had never been to or benefitted from. A protracted guerrilla war ensued.

In 1963, a full two years after the start of hostilities, the regime organized a massive rally in Lisbon’s main square, attended by thousands. In his speech, Salazar set the tone for what to expect from the war. “The fathers and mothers of the Portuguese who are here, in jubilation or in tears, came not to ask for anything but to offer in sacrifice to the Homeland the blood of their own and their purest affection,” he exclaimed. “All is well as it is, and it could not be otherwise.” This was not so much a rallying cry for the defence of the country, but a call to abandon all hope. War was to be the new “living habitually.” The wars in Africa would drag on for another 11 years.

War was to be the new “living habitually.” The wars in Africa would drag on for another 11 years

At its the war’s peak in the late 1960s, Portugal was devoting a full 40% of the national budget to the military effort. And yet, critical supplies like ammunition and basic rations were missing from the front lines. As so often happens when a corrupted military establishment receives a substantial budget, a huge part of the military supply chain was lost through corruption at the higher echelons. This fuelled a huge mistrust between the lower army ranks and the top brass of the armed forces, beginning a gradual process of politicization in the middle levels of the military. The regime unwittingly helped along this process. In 1968, an ageing Salazar literally fell off his chair in the fortress retreat near Lisbon where he used to vacation, suffering a massive cerebral haemorrhage. He was replaced by another academic, Marcello Caetano, who promised the country a breath of openness. Caetano called it “evolution in continuity,” but the hopes of gradual democratization were short-lived, as the regime was not able to substantially alter its policy on decolonization or allow basic political freedoms. By 1969, a huge protest movement had broken out in universities across the country. As retaliation, many of the students leading the protests were forcibly drafted into the military, where they ended up organizing opposition from inside the armed forces. By 1974, Portugal was exhausted by war and fed up with an absolutely corrupted and out-of-touch autocracy.

The bloodless coup

Dictatorships fall when people’s fear of the violent present is outweighed by their fear of a hopeless future. When we lose all pretence that a better day might lie ahead, courage turns from a dangerous romantic notion into the only thing we can cling on to. That’s how, early in the morning on April 25, 1974, army captain Salgueiro Maia formed his men at the Army School of Cavalry in Santarém, about 80 km north of Lisbon, and announced they were moving on the capital to topple the regime. It was his column that occupied the same square from which Salazar had made his hopeless rallying cry in 1963. The coup was won, tactically and symbolically, that same morning, when two military columns dispatched to confront Salgueiro Maia simply refused to fight for the regime. After 48 long years, the old “New State” fell like overripe fruit dropping from the tree.

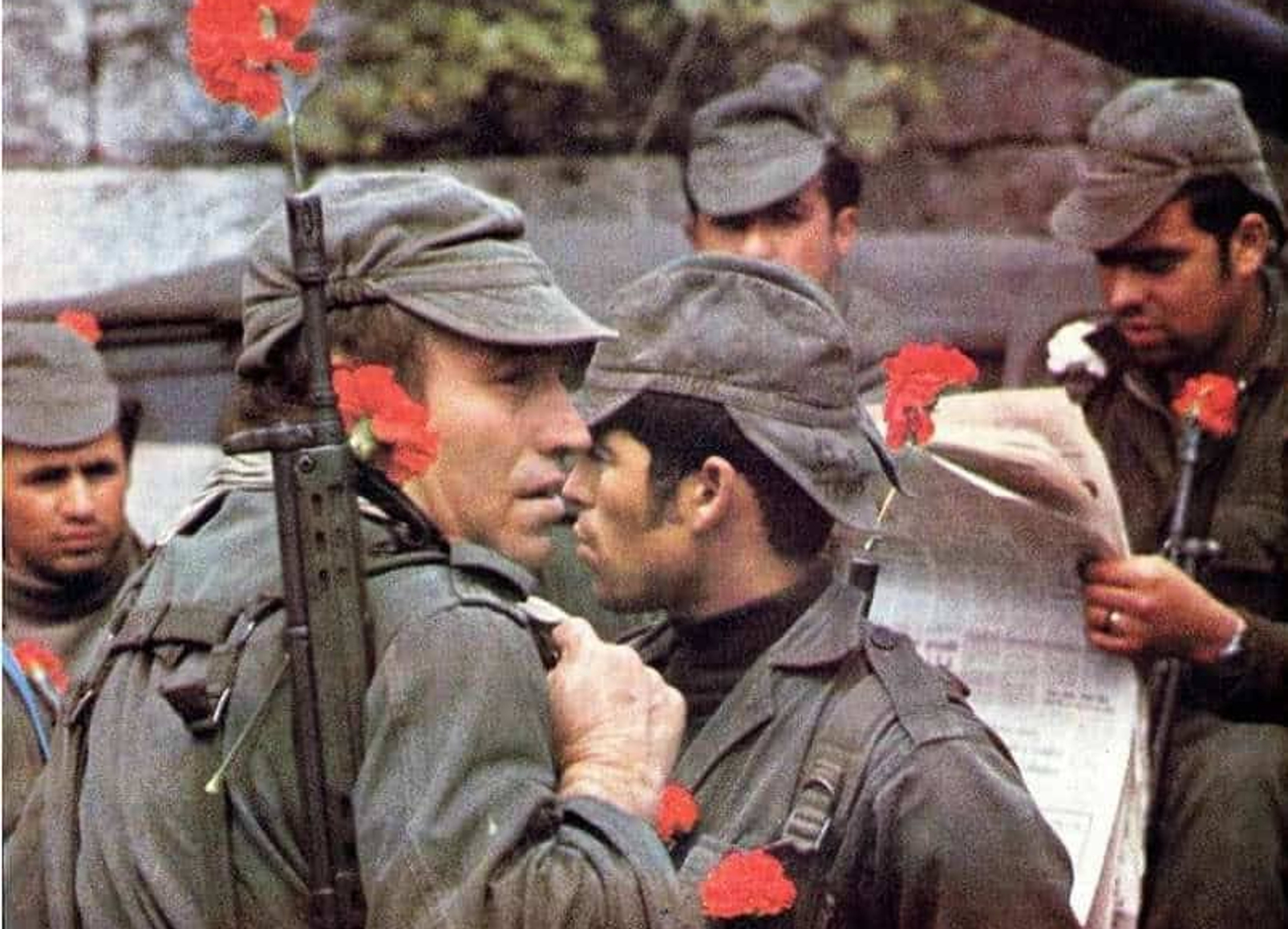

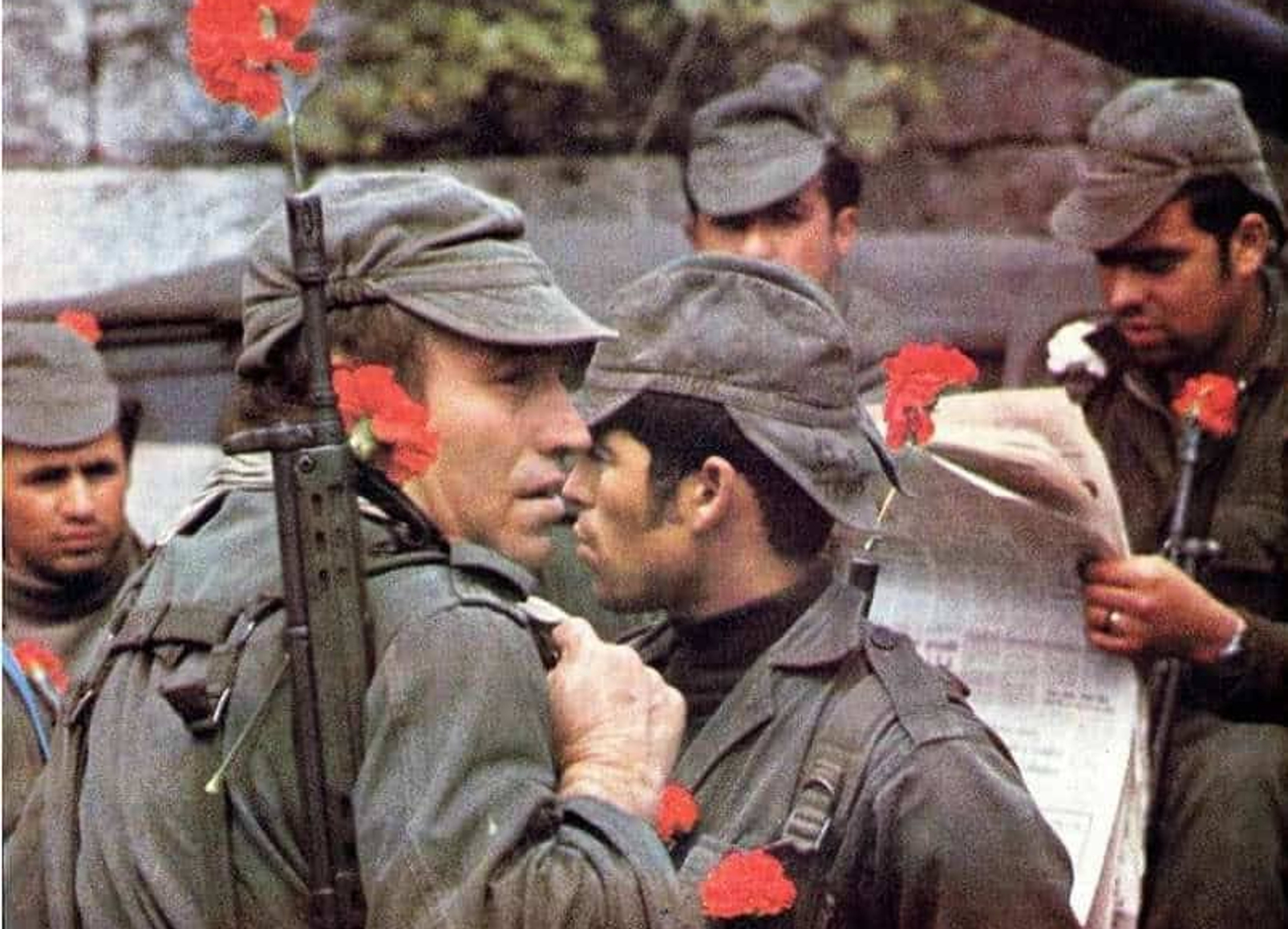

Along with the military, thousands of civilians descended on Lisbon, cheering on the troops and celebrating the fall of the dictatorship. Salazar’s successor, Marcello Caetano, holed up at the headquarters of the National Guard in the centre of the city, but the building was quickly surrounded by Salgueiro Maia’s soldiers and thousands of citizens demanding the national leader’s surrender. With no one willing to fight for him, Caetano negotiated his way out and was taken by the army to the island of Madeira. From there, he left for exile in Brazil, where he would die in 1980. The longest dictatorship in Western Europe fell without any armed conflict. The only victims of that liberation day 50 years ago were five people who were part of a large group of civilians surrounding the headquarters of the political police. They were shot by officers firing on the crowd from inside the building.

Lisbon, April 25, 1974

Photo: Associação 25 de Abril

Poet Sophia de Mello Breyner Andersen summarized the events of 50 years ago as “the initial day, whole and clean.” Another writer, Vergilio Ferreira, penned in his diary of the powerful emotion he felt as a result of the victory of the revolution. His apt summary of the old regime read: “almost 50 years of fascism. An entire life deformed by fear.” By April 1974, the flame of fear had burnt through its fuse. There was nothing else to do but to raise the courage to defeat it and start anew.

The “revolutionary process”

When a regime falls by exhaustion, you don’t get to know what happens next right away. The Armed Forces Movement that toppled the dictatorship had a minimal political programme consisting of three Ds: Decolonization, Democratization, and Development. Portugal was one of the poorest countries in Western Europe, with the highest rate of infant mortality on the entire continent. Over half the households didn’t have tap water and 43% had no indoor plumbing. When the old dictatorship unravelled, there was also no political alternative ready to take its place. We were forced to figure out what kind of regime we wanted to build as we were building it.

Portugal was one of the poorest countries in Western Europe, with the highest rate of infant mortality on the entire continent

In a single-party system such as the Estado Novo, there was no institutionalized opposition. The Socialist Party had been formed in exile only in 1973. The Communist Party had been resisting as a clandestine organization and had the only political structure covering the entire country, with considerable influence among the working class, the new political elites, and, crucially, among large swaths of the armed forces. After the fall of the dictatorship, all other political parties formed in a rush to join the debate on how to move into a democratic system.

In those early days, much of the discussion was dominated by the Communists and far-left movements, which advocated for a Soviet-style regime or various forms of “direct” or “popular” democracy as opposed to a “bourgeois” electoral democracy, which they claimed would be fundamentally unrevolutionary. It was during this somewhat chaotic transition that elements of the Portuguese Communist Party appointed to the commission overseeing the extinction of the political police, PIDE, were rumoured to have passed secret documents to the KGB. Although the Communist party to this day denies any relationship with the Soviet security and intelligence services, much sensitive information from the PIDE archives would later be found in the Mitrokhin Archive, exfiltrated from Russia by former KGB senior archivist Vasili Mitrokhin, who defected to the UK in 1992. The Cold War had been contested in Portugal — and, crucially, in the destiny of its former colonies.

The power struggle during the transition had other consequences. In 1975, the provisional government nationalized the main economic groups, from finance to industry, effectively decapitating the old economic oligarchy and installing a number of State-run monopolies. Political parties promoted land occupation movements that essentially collectivized agricultural production, especially in the south of the country, where big estates belonging to the old families of privilege were located. Portugal changed radically in two short years.

A European democracy

The Portuguese transition was a fight between moderate political parties and more radical left-wing movements over the shape and functioning of the new regime. Each of these forces had their own allies in the armed forces, which, in the immediate aftermath of the revolution, retained considerable power in the country. The nation was heavily divided. The first free elections for a Constitutional assembly took place on the first anniversary of the revolution, in 1975. They handed power to the more moderate parties, the socialists and the social-democrats, both aligning on the centre-left (today’s social-democrats have since shifted to the centre-right).

The Constitution adopted a year later, in 1976, proclaimed Portugal to be a country “on the path to socialism,” but the political model it adopted was very much that of a Western-style multiparty democracy. By that time, power had also been handed over to the liberation movements in Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, and the rest of Portuguese former colonies. The old myth of the “pluricontinental nation” was dead.

The Constitution, adopted in 1976, proclaimed Portugal to be a country “on the path to socialism”

With its empire gone, Portugal looked to Europe to find its new identity. In that sense, accession to the European Union in 1986 was the last chapter in our political transition. It repositioned the country as a member of a family of democratic nations, as opposed to a stubborn colonial occupier openly condemned at the United Nations and shunned by its own historical allies.

Europe is today at the core of Portuguese identity. The influx of European cohesion funds allowed the country to rapidly develop its infrastructure and the qualifications of a population whose education standards lagged tragically behind the European average. Today, Portugal retains high levels of support for the EU, even if political debate on European matters mostly revolves around EU subsidies and how they are to be spent. Beyond that, though, EU membership was crucial to stabilizing political institutions and deepening the rule of law. Fundamentally, it gave the Portuguese something to look forward to, an expectation of development and the ambition to achieve a standard of living similar to the most prosperous nations in Europe.

The import-export of corruption

But not everything changed, as it turns out. EU membership came with new economic policies built on a consensus of dismantling the State-run monopolies created in 1975. The liberalization of the economy was made mainly through the privatization of the old, nationalized companies.

However, an opportunity to open Portuguese markets to new domestic and foreign investment was instead developed into a return to the old oligarchic system. The same old families who had been stripped of their assets during the revolutionary transition were handed back their holdings, often on very favourable terms and with financing from the State itself. The economic make-up of the new democracy ended up very similar to that of the old dictatorship.

The poster-boy for this reestablished elite was Ricardo Espírito Santo Salgado, grandson of the old tea-companion of Salazar — his nickname was “the owner of all this” — for the immense power and influence he wielded until the family banking and financial businesses went bankrupt in 2016. Salgado is currently facing multiple criminal indictments.

The economic make-up of the new democracy ended up very similar to that of the old dictatorship

50 years after the “initial day, whole and clean,” many of the toxic relations between the economic and political elites are back. Two generations on, Portugal exhibits most of the same vices of old colonial powers – namely, the exploitative nature of its approach to international relations. The consolidation of democracy and the opening of markets also coincided with a fondness for doing business with shady dictators and laundering stolen assets from abroad. Europe, and the European Union in particular, likes to present itself as the great defender of democracy and human rights in the world. But it is also in Europe that foreign dictators turn to for discreet banking services in the city of London, Switzerland or Luxembourg, or luxury items from Belgian diamonds to French fashion, to high-end real estate in Spain or Portugal. Peaceful, “civilized” Europe continues to be a haven for the authors of misery, instability and destruction elsewhere in the world.

Portugal entered this “import-export” market for corruption fairly late, after the financial crisis of 2008-2010. But we entered in force. In 2012, we created a Golden Visa programme that grants wealthy foreigners expedited residency permits that include the right of unrestricted travel through Europe. Although the scheme poses massive security threats and has been exposed as a huge money laundering risk, it continues to this day.

Portugal entered the “import-export” market for corruption fairly late, after the financial crisis of 2008-2010 — but it entered in force

Beyond that, Portugal in 2013 amended its nationality law to allow the naturalization of any descendants of Portuguese Jewish communities expelled from the country at the end of the 15th century, the result of a religious intolerance decree by then King Manuel I. But crucially, the law empowered the Jewish communities of Lisbon and Porto to freely certify the ancestry of applicants, which in turn allowed for massive abuses, and many cases are currently under judicial investigation. It was under this law that Russian oligarchs like Roman Abramovich obtained Portuguese citizenship, allowing him some degree of protection from EU sanctions imposed in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In Portugal, as in several other EU countries, implementation of war sanctions against Russian oligarchs and political leaders are himdered by a lack of political will that renders effective punishment against corruption and abuse virtually non-existent. This infiltration of established democracies by corruption, foreign and domestic, is today the greatest threat not only to the quality of those democracies, but to their very existence.

In 2017, Angolan journalist William Tonet, himself a former freedom fighter in the colonial independence wars, proposed that the Armed Forces Movement that toppled the Portuguese dictatorship 50 years ago be recognized as the fourth liberation movement, after those of Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau. After all, he argued, without the removal of the old regime, the independence struggle of the liberation movements would have dragged on for years more. But the opposite is also true: without the fight for freedom that started in Africa, the Portuguese armed forces would never have rebelled against their own undemocratic government. In that sense, the colonized and the colonizers liberated each other.

50 years after the fall of that rotten empire, if Europe is to be fully free, democratic, and peaceful, the peoples of Europe also need to liberate each other — to fight the forces of corruption and oppression and demand liberty and equality for all. The lesson of our past, and the experience of our urgent present, is that the four freedoms laid out by Franklin Roosevelt in 1941 — freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear — are indivisible. None of us get to enjoy them, on the Western or the Eastern tips of Europe, until we’ve secured them for us all.