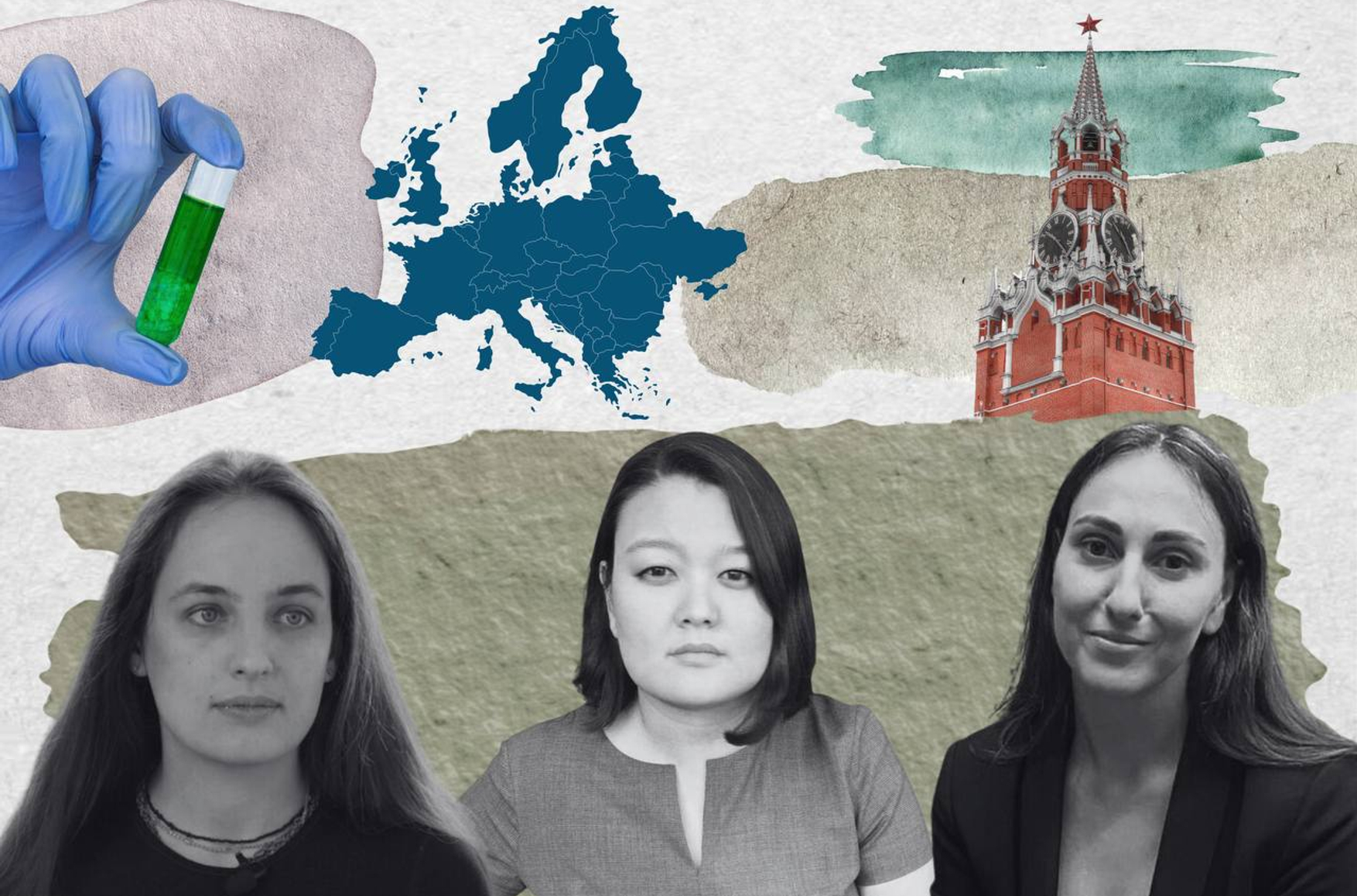

Elena Kostyuchenko, Natalia Arno, and Irina Babloyan, have long worked to expose the Kremlin’s lies. While traveling through Europe in the last year, each was poisoned by unknown toxins. Their cases remain unsolved. Why?

“You cannot return to Russia. You will be killed here.”

Dmitry Muratov, the editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta, didn’ not explain how he came to this dire conclusion, but he said he wasn’t taking any chances. His foreign correspondent, Elena Kostyuchenko, who had documented Russian war crimes in occupied Ukraine, had already been warned that she was in danger and he advised her to stay in Europe. Muratov was right.

Six months later, Kostyuchenko would find herself suffering from an acute pain in her abdomen, insomnia, nausea and an extreme case of anxiety. Her face, fingers and toes swelled; her palms turned red and ballooned in size before returning to normal. Something was seriously wrong with her but she didn’t know what.

Kostyuchenko was very likely poisoned.

That, at least, is the conclusion of a half dozen doctors, scientists and chemical weapons experts whom The Insider has consulted about her case, which has not been publicized until now. And Kostyuchenko isn’t the only suspected poison victim. She is part of a trio of muckraking Russian journalists and dissidents — all of them women, all outspoken critics of Vladimir Putin’s regime, and all living and working in different countries outside of Russia — who in the past year have succumbed to a similar set of strange and alarming physical ailments, with circumstantial evidence suggesting foul play. They’ve found their hotel doors mysteriously prised open, unusual smells lingering in the air of their living quarters, or emanating from their own bodies, as well as meals they’ve eaten utterly lacking in taste. The European and American authorities these women have relied on for answers have been unable (or unwilling) to do so.

Their unsolved cases, which have all begun after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, follow series of uncannily similar poisonings of other enemies of the Kremlin over the past decade with targets as diverse as Emilian Gebrev, a Bulgarian arms dealer; Sergei Skripal, a British spy who years earlier defected from the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency; Alexei Navalny and Vladimir Kara-Murza, Russian opposition figures who canvassed and agitated extensively around Russia. These poisonings, as The Insider was the first new outlet to determine, were conducted with the military-grade nerve agent Novichok and perpetrated by operatives from the Russian special services.

***

To hear the 36 year-old Kostyuchenko tell it, her story begins on March 28, 2022, the day Novaya Gazeta, one of the last remaining (at least partly) independent news outlets in Russia, published a dispatch from occupied Kherson about the torture and kidnapping of Ukrainian civilians at the hands of Russian soldiers: her subjects were handicuffed to radiators and beaten with rifle butts, their children dragged away with bags over their heads. Two days after her story was published, Novaya Gazeta, founded in 1993, decided to close up shop after receiving a second notice issued to it by Russia’s Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media, Roskomnadzor. Two notices from this bureaucracy usually indicate that a criminal proceeding is imminent. Given the Russian penalty for spreading “disinformation” about the war in Ukraine — which basically amounts to telling the truth about it — is up to 25 years in prison, Muratov preemptively “suspended” the newspaper whose pathfinding investigative reporting won him a Nobel Peace Prize in 2021. A total of seven Novaya Gazeta journalists, among them Anna Politkovskaya, Yuri Shchekochikhin, and Anastasia Baburova, have been murdered over the years for their investigative spadework.

The shuttering of her newspaper did not deter Kostyuchenko.

Elena Kostyuchenko

She was then based in Zaporizhia, in southeast Ukraine, and planned to travel to Mariupol, then still a fiercely contested port city in Donetsk, to chronicle more of the Russian army’s activities. But on March 30, Kostyuchenko received a call from another Novaya Gazeta colleague. “My sources contacted me. They know that you are going to Mariupol. They say the Kadyrovites have an order to find you,” the colleague told her, referring to Chechen fighters loyal to Ramzan Kadyrov, the warlord president of the Republic of Chechnya.

Kostyuchenko’s travel, of which she had only informed two people — Muratov and her editor Olga Bobrova — was evidently also known to nefarious actors within Russia’s military presence in Ukraine. As proof, her colleague played an audio tape of Kostyuchenko discussing her trip to Mariupol with a third party, an obvious sign her lines were tapped, most likely by the Federal Security Service, or FSB, which had purview over Russia’s occupation zones.

Kostyuchenko recalled an odd sight from her time in Kherson: that of a car parked for two nights in a row — both nights arriving after the 11 p.m. curfew the occupiers implemented — outside the apartment she’d stayed at. The car’s headlights were on. At some point on one of the nights, a man exited the car and seemed to be surveilling Kostyuchenko’s building. By the time the car was gone, she’d noticed a convex piece of equipment installed on the roof, like a satellite dish, with a long antenna sticking out of it.

Photo of the car that drove up to Kostyuchenko's house

Less than an hour after that colleague's call, a source from Ukrainian intelligence got in touch with Kostyuchenko. The murder of a Novaya Gazeta journalist was being planned in Ukraine, the source told her. Her name was now given to every checkpoint on the route she’d have to take from Zaporozhye to Mariupol. Muratov rang her next. “You can no longer go to Mariupol. You must leave Ukraine right now.” Confronted with such an array of alerts, Kostyuchenko decided not to take chances by staying in Ukraine any further. She reckoned she could wait out the threat in Europe and also finish the book she’d begun writing on “how Russia came to fascism.”

She chose Germany as her new home, a country in the heart of Europe where she thought she’d be safe, even though Russian assassins have plied their grim trade there, too, most recently with the August 2019 daylight murder of Chechen dissident Zelimkhan Khangoshvili, who was shot at point-blank range by Vadim Krasikov, an asset of the FSB, in Berlin’s Tiergarten park.

Kostyuchenko’s calm existence did not last long. In April 2022, Muratov called again with the news that she could not return to Russia for the foreseeable future. If she did, she’d be killed.

So Kostyuchenko rented an apartment in Berlin and found a new job in journalism, working for the independent, Vilnius-based, Russian news site Meduza. Her first planned foreign assignment for the outlet was going to be in Iran. “I had been to Iran and knew how to work there,” Kostyuchenko said. “I found people who would help me, got a visa, and bought clothes. We decided that the second business trip would be Ukraine.”

Her prospective travel to Ukraine was hampered by a cyberattack on the Ukrainian embassy in Berlin, which temporarily disrupted the processing of visa applications. This meant that Kostyuchenko had to travel to Munich to get a visa — now required for all Russian citizens — from Ukraine’s consulate. It was 9:30, on the evening of October 17, and Kostyuchenko boarded the night train to Munich. She took off her shoes in the car, and lay down on the seats to sleep for the five-hour journey.

The following morning, Kostyuchenko arrived in the city and met a female friend at the latter’s apartment, where she slept for another hour before making her appointment at the consulate. The same friend (whose name The Insider has agreed to withhold at Kostyuchenko’s request) picked the journalist up by car. The two went to lunch at a local cafe and sat outdoors. The food had no taste, according to Kostyuchenko; she left half her plate untouched. During the course of the lunch, three of the friend’s acquaintances turned up at the cafe, a man, and then two other women. Kostyuchenko remembers wondering if Munich is such a small town that so many familiar people could saunter past the same cafe in the space of an afternoon. Elena excused herself to use the bathroom, perhaps more than once — she can’t quite remember. At around 3:30 p.m. Kostyuchenko and her friend drove back to the train station. During the car ride, Kostyuchenko detected a weird smell coming from her body, not typical body odor. Her friend, normally shy and polite, told her, “You know, you smell bad. I'll look for deodorant.” But she couldn’t find any.

Kostyuchenko boarded her return train and went to the toilet. Her friend was right about the odor; “I soaked the paper towels and began to dry off,” Kostyuchenko recalled. “It turned out I was sweating a lot. The smell of sweat was sharp and strange -- the smell of rotten fruit.”

The train left Munich station at 4 p.m.. She flipped open her laptop and began to edit the text of her manuscript. Before long, she realized that she was rereading the same paragraph over and over again. Her head was pounding and she couldn’t concentrate. At first, Kostyuchenko thought maybe she’d contracted Covid again. She’d tested positive for the virus three weeks earlier. Another bout would surely scupper Kostyuchenko’s planned trip to Iran, as her girlfriend Yana told her on the phone.

At 8 p.m. her train pulled into Berlin. As Kostyuchenko stepped onto the platform, she realized her strength was gone, as was her ability to focus. With great difficulty she found her way from the station to the subway, and from there to her stop in the German capital. The walk from the subway station, normally no more than five minutes, took fifteen, as Kostyuchenko found her bag enormously heavy and also that she was short of breath. “On the platform, I burst into tears,” she said. “I didn’t understand what direction to go. Other passengers helped me.”

As soon as she reached her apartment, she collapsed on her bed and fell asleep. Kostyuchenko’s girlfriend Yana told The Insider that she looked normal when she arrived, just very tired, and her heart was beating very fast.

The next morning, Kostyuchenko awoke with a severe pain in her abdomen, a bit higher than her stomach. The pain radiated to her spine and she experienced such bad vertigo that she couldn’t get up from bed. Her worst symptom would be insomnia; on the rare occasion that she did get some sleep, the pain in her body would put an end to any respite. Kostyuchenko was also nauseated and sometimes threw up. Rather than call an ambulance, she made an appointment with a clinic, who saw her 10 days later, on October 2. Two doctors informed her she was probably suffering aftereffects of Covid and that she’d recover in six months. They performed an ultrasound and took some blood. Kostyuchenko, her blood screening found, had elevated liver enzymes Alanine transaminase (ALT) and Aspartate transaminase (AST) — five times higher than normal and not associated with Covid. She also had blood in her urine, another condition not linked with the pandemic.

Kostyuchenko was tested for viral hepatitis, in case it was acquired from her foreign travels, but the result was negative. In time, the pain in her abdomen and the dizziness subsided; Kostyuchenko just felt weak and nauseated. Although now new symptoms appeared including palmar-plantar syndrome, the discoloration and swelling of her palms. “The swelling got bigger, my jaw line disappeared, my face was not my face,” Kostyuchenko remembered. “In front of the mirror, I needed time to recognize myself.” She couldn’t get a decent night’s sleep.

One Russian doctor in Berlin, who had previously tended to victims of Russia’s state-sponsored poisoning program including Alexei Navalny and popular author Dmitry Bykov, studied her case at the request of Kostyuchenko’s employers at Meduza. The doctor, who has requested we not name him out of safety concerns, first suggested Kostyuchenko may not be suffering from any natural ailment. As she drove home from the hospital, the doctor texted her: “Is there a possibility you might have been poisoned?” She wrote back: “No, I'm not that dangerous.”

But by November, all other explanations for why she felt so sick were tested and dismissed. On December 12, Kostyuchenko’s ALT level was now seven times higher than normal. Doctors said she had one recourse left, to get tested by specialists at the Charité university hospital in Berlin, the same hospital that treated Navalny after his poisoning in 2020.

In order to test for toxins, however, Kostyuchenko had to file a criminal report with the Berlin police, which she did. She was interrogated for nine hours; her case was handled by the same German investigator who examined the evidence of Khangoshvili’s assassination. He also investigated the poisoning of Pyotr Verzilov, the producer of punk activist group Pussy Riot, who was exposed to a nerve agent in September 2018 after he ran through the soccer field during the World Cup final match, chased by Russian police in a Benny Hill-like sequence in front of Putin, who was watching in attendance.

The investigator was annoyed that Kostyuchenko waited so long to contact law enforcement; now, two and a half months after her initial symptoms, it would be almost impossible to find any traces of toxins in her body. Kostyuchenko’s refusal to accept that she might be the target of an attempted assassination exasperated the German investigator. “That's what you’re pissing us off. You arrive here and think you are on vacation. It's like paradise here. You don't think that you need to be careful. We have political killings here. We have Russian special services. Your carelessness, yours and your colleagues, is beyond [comprehension].”

Kostyuchenko’s apartment and belongings were checked for radiation, as was she. “They took away the things I was wearing in Munich,” she said.

Two days before Christmas, at the prompting of Berlin police, Kostyuchenko was checked into Charité. Doctors there took blood in sufficient quantities to be able to conduct several screenings at once. But when Kostyuchenko requested the results of the tests from the police, they said there’d be a miscommunication and her blood had only been tested for alcohol, narcotics and a concentration of the antidepressants Kostyuchenko was taking. Kostyuchenko’s lawyer asked if the doctors would continue to test her blood, this time for toxins. The police answered that there weren’t enough samples left in Charité’s laboratory for a new analysis. On January 23, an expert invited by the police tried four times to take Kostyuchenko’s blood, each time finding that her blood was “too thick” to take a sample. When Kostyuchenko asked the clinic to find her another expert, the police told her that looking for one would be a “bureaucratic nightmare” and asked Kostyuchenko if her supervising doctor could take blood samples and pass them to the police. Doctors at the clinic Elena had been treated at said they are not able to comply with the legally required chain-of-custody rules and that it was up to the police to organize another testing.

By February 20 the police had given up, telling Kostyuchenko’s lawyer that too much time had passed since the possible poisoning for adequate forensic analysis. On May 2, the German prosecutor’s office informed the lawyer that they were closing the case due to lack of evidence for a criminal investigation. On July 21, the office reopened it pending additional tests.

The Insider spoke to a host of medical experts, doctors and chemists experienced in diagnosing poisonings including a former lead chemist at the Organization for the Prohibition for Chemical Weapons, the international watchdog. All agreed that Kostyuchenko’s symptoms cannot be explained by anything other than exogenous poisoning. Her toxicology indicated acute damage to the liver (thus the significant increase in ALT and AST enzymes) and kidneys. The experts believe Kostyuchenko was exposed to some kind of organochlorine compound, such as dichloroethane. And they further suggest that the poison was absorbed through the skin or ingested.

***

“I thought I had a toothache and needed to go to the dentist,” Natalia Arno told The Insider. “I wasn’t even thinking about poisoning.”

The 47 year-old president of the Washington, D.C.-based Free Russia Foundation, a U.S. non-governmental organization that supports Russian activists, journalists and pro-democracy organizations, has built one of the most effective American NGOs advocating on behalf of dissidents, not just Russians but Belarusians and Kazakhs in exile. The foundation also works to get Ukrainian prisoners of war released from Russian captivity.

The Free Russia Foundation was already declared both an “undesirable” organization in Russia before it played an instrumental role in helping the U.S. government develop a sanctions regime against Putin’s entourage. “We were told our sanctions report was on Putin’s table in early February,” Arno said. Her vice president, Vladimir Kara-Murza, a fellow Washington, D.C. resident, was poisoned twice with Novichok while traveling through Russia. In April, Kara-Murza was sentenced to 25 years in prison after having been arrested months earlier for speaking out against the war in Ukraine on the American cable news channel MSNBC.

On May 2, 2023, Natalia Arno participated in a private event in Prague, after which, at around 7:30 p.m. she returned to her hotel, the Garden Court Hotel in the city center. Arno at once noticed the door to her room was open and she’d remembered closing it. Nothing was missing and everything seemed as she’d left it except for a strange odor resembling perfume, which hadn’t been there before. Reception told her the maid had probably left the door open and promised to look into it. Arno went to sleep at around 2 a.m.

The Garden Court Hotel in Prague

At 5 a.m., she awoke in agonizing pain. Her teeth and tongue were especially sore, and she figured she had a dental problem. She took painkillers, but they didn’t work. A few hours later, the pain began to spread further, as if “wandering” through her body: it was in her ears, chest, armpits, and spine. Arno also noticed a “stone” or mineral taste in her mouth. Her vision got blurry. Then her arms and legs went numb.

This wasn’t the first time Arno had returned to a hotel room that bore signs of trespass. At the end of July 2021, she attended an event in Vilnius, where she met with activists. While on that trip, she also detected a perfumey smell in her room, albeit weaker than what she experienced now. In Vilnius, she’d broken out in a fever and felt weak, as if stricken with the flu or a cold. The rash soon spread all over her body and she has no known allergies.

Like Kostyuchenko, Arno waited before seeing a physician, and she didn't see one in Prague. “If I had the slightest suspicion about poisoning I wouldn’t have done the transatlantic flight, but went to the clinic in Prague and to the U.S. Embassy in Czechia,” she told The Insider. Instead, she changed her tickets to catch an earlier flight home to Washington, where she immediately sought medical help. She checked into Inova Alexandria Hospital, in Alexandria, Virginia.

On May 4, she passed all her blood tests, but the oddity of her symptoms added to the suspicious state of her hotel room convincer her to contact the FBI. “They took my blood work, did some other tests and questioned me several times,” Arno said. “They took my suitcase and the clothes I was traveling in. One thing they found was an increased level of lead, which may have been due to environmental reasons. They came back a few weeks ago, took more of my clothes and toothpaste and promised to finish the investigation as soon as possible. The first time they came with experts from their chemical laboratory; recently, they brought guys from the biological laboratory. The FBI didn’t say this publicly at time but when they first came to the ER in early May and took the first batch of tests, they said it wasn't Novichok.”

While the FBI may have ruled out that family of Soviet-developed nerve agents, Arno’s doctors maintain she was indeed poisoned, specifically by “nerve toxins.”

***

In mid-October, Irina Babloyan, a 36 year-old journalist with Russian radio station Ekho Moskvy, relocated from Moscow to Tbilisi, Georgia. She moved into the King Tamar Hotel. On the evening of October 25, Babloyan felt lousy. The next morning she woke up with severe weakness and dizziness.

That night, her palms turned purple and burned as if she were literally playing with fire: Babloyan, too, developed palmar-plantar syndrome, and it soon spread to her feet. Paying little mind to her symptoms, she decided to stick with a planned holiday in Yerevan, the Armenian capital, where she traveled from Tbilisi on the night of October 27. In the car, which someone else was driving, she became very ill. Babloyan’s mind was cloudy and she couldn’t concentrate: “I had a feeling that my body was no longer mine; it felt like cotton and I experienced intense anxiety.”

Irina Babloyan

Arriving at her hotel in Yerevan, Babloyan asked for a thermometer. She went up to her room, but couldn’t fall asleep. She felt nausea and aching pain north of her stomach, the same as Kostyuchenko. There was a metallic taste in her mouth. Babloyan’s skin on different parts of her body turned red. The pain, weakness and insomnia went away after about two days, but the redness persisted.

As with Kostyuchenko and Arno, Babloyan didn’t panic enough to see a toxicologist right away. She limited her concerns to have herself tested for allergies. The tests came back negative.

After moving to Berlin a few months later, and having continuing symptoms such as rashes and insomnia, Babloyan submitted blood samples for toxicology testing at the Charité hospital. However, several days later the clinic told her that her samples had been “lost”. Irina was then approached by police investigators who questioned her about the events leading her to suspect poisoning. Following the alleged loss of the initial samples, Babloyan submitted tests anew (results are still pending at press time).

According to the experts interviewed by The Insider, the clinical picture described by Babloyan cannot be convincingly explained by a disease; exogenous poisoning seems to them the most reasonable diagnosis. The experts agree, however, that discovery of the toxin (or toxins) is now unlikely given the elapsed time period since the presumed exposure.

***

Although their ordeals in the last year remain unexplained, Kostyuchenko, Arno and Babloyan continue to work from abroad. Babloyan is still broadcasting for Ekho Moskvy from Berlin. Arno remains in the U.S. but has traveled to Europe in recent months as part of Free Russia Foundation’s events, taking, as she told The Insider, the best possible security precautions under the circumstances. Kostyuchenko’s book on Russia’s descent into fascism is due out in a few weeks, and the German police have told her the publicity may do her no favors given that whoever was sent to kill her in Ukraine or Berlin could well be incentivized to try again.

Kostyuchenko has written her own recollection of her suspected poisoning in Russian for Meduza. She urges any other Russians who have fled their homeland and now reside overseas to be careful and to immediately report unusual physical symptoms to medical professionals — also to get in touch with The Insider, which is actively investigating all suspected cases of poisoning.

It doesn’t pay to think oneself too harmless to be a target, Kostyuchenko now insists. “I want to live.”