A joint investigation by The Insider, Bellingcat, and CNN with a contribution from Der Spiegel has revealed the names and ranks of the FSB officers responsible for poisoning Alexei Navalny with Novichok. The findings suggest that the poisoning in Tomsk was the second attempt: two months prior, the same officers launched another assassination attempt on the politician in Kaliningrad, almost killing his wife Yulia Navalnaya in the process. The key role in the operation belonged to a special unit of the FSB Criminalistics Institute.

Content

The Lab: What is it?

Poisoners from the FSB

37 “Coincidences”: How the poisoners spied on Navalny

The Kaliningrad fiasco

The ultimate attempt

Tying up loose ends

The Bellingcat version is available here

Once The Insider and Bellingcat analyzed phone billing data of the Skripals’ poisoners and uncovered evidence that the GRU officers had been receiving the Novichok agent from SC Signal, it became possible to investigate a few more poisonings. Analyzing the SC Signal director Artur Zhirov’s phone metadata (obtained by Bellingcat), we identified a few FSB officers who maintained close contact with him. This was how we discovered his connection to the FSB Criminalistics Institute (commonly known as the NII-2), which supplied the assassins from among its chemical weapons experts (again, as shown by phone records).

The Lab: What is it?

Phone records and travel data suggest that Navalny’s poisoning was an operation involving at least eight FSB operatives from the agency’s clandestine unit acting under the cover of the FSB NII-2 (also referred to as Military Unit 34435).

Founded in 1977 as a technology-intensive investigation unit of the KGB, the FSB Criminalistics Institute is a multi-faceted organization providing services that range from polygraph tests and facial or voice recognition to robotic mine clearing. The unit was instrumental in the investigation of all major incidents in the post-Soviet period, such as explosions in residential buildings in 1999, the wreckage of the Kursk submarine, the school siege in the North Ossetian town of Beslan, the hostage crisis at the Nord-Ost musical performance in Moscow, and the explosions on St. Petersburg subway (although independent journalists questioned the objectivity of their investigation efforts in all of the cases). Other achievements advertised by the unit are more esoteric, including the purported ability to deduce a person's height and education based on their speech sample and investigate the circumstances of Jesus Christ’s final days on earth. The very same institute “detected” drugs in persecuted journalist Ivan Golunov's hair samples (the results of its analysis were later proven to be false). Its experts also dabble in linguistic analysis: Alexander Korshikov and Anna Osokina found extremism in a statement of High School of Economics student Yegor Zhukov, who said that “the system must be fought rigorously and consistently”.

Whereas the official purpose of the NII-2 is to conduct expert studies, Russian and Soviet spies who defected to the West revealed that the institute was also in charge of a secret lab where the USSR produced poisons for the assassination of Western diplomats, Ukrainian nationalists, and Soviet turncoats. As former KGB general Oleg Kalugin recalls, one of the lab's first projects was a special bullet (a tiny ball with two orifices) filled with ricin, which the KGB used to assassinate Bulgarian writer Georgy Markov, who had emigrated from the Soviet bloc to find his death in London in 1979. Another KGB defector, currently a US resident, has shared with Bellingcat anonymously that the KGB's main poison lab was in the exact same location where we identified the institute’s operative center for poisonings. The defector also asserts that the KGB lab's location was so strictly classified that putschists chose it as their “situation room” in August 1991.

A 2007 Gazeta.Ru article (currently available only as an archived copy) reported that the polonium used in Alexander Litvinenko's assassination in London in 2006 had also been supplied by the NII-2. Examining the phone billing records of twelve FSB officers with ties to the Criminalistics Institute, we found evidence that the division is still running a chemical weapons lab housed in two clandestine, tightly guarded facilities in Moscow and the Moscow Region. The main compound is located at the intersection of Akademika Vargi Street and Teplostansky Thoroughfare.

The compound in Akademika Vargi Street housing the FSB's NII-2, whose employees tried to poison Navalny

The lab's secondary facility is a compound in Podlipki near the town of Korolyov, Moscow Region. Operative officers implicated in the poisonings also frequent the administrative headquarters at the Institute’s head office: the Center for Special-Purpose Equipment at 12 Vernadskogo Avenue.

The FSB Criminalistics Institute is headed by General Kirill Vasilyev, a chemical engineer and expert in identifying chemical metabolites in biomedical samples with mass-chromatography and mass-spectrometry (the golden standard of chemical weapons detection in biomedical samples). Without disclosing his appurtenance to the FSB, he also contributes to studies of SC Signal, which we identified in our previous investigation as the key participant in Russia’s renewed clandestine program of Novichok research and development.

General Vasilyev, in turn, reports to Major General Vladimir Bogdanov: the former head of the Criminalistics Institute, current chief of its head organization, the FSB's Center for Special-Purpose Equipment, and Deputy Director of the FSB’s Scientific and Technical Service.

Major General Vladimir Bogdanov

Poisoners from the FSB

Analyzing phone call metadata and matching it to offline databases and open-source data, we identified 15 FSB Criminalistics Institute employees linked to poisoning operations. At least eight of them – including Colonel Stanislav Makshakov, the leader of the group – were complicit in Navalny's assassination attempt. (Incidentally, the group of GRU poisoners that we covered in The Poisonous Eight also consisted of eight members.) The assassins have varied backgrounds: medical degree holders; ex-military or the FSB's Spetsnaz officer, and chemical weapons experts. We offer you the brief bios of the main perpetrators of the failed assassination:

Stanislav Makshakov

Stanislav Makshakov

Born on March 25, 1966. An army colonel and military scientist who used to work in the restricted military town of Shikhany-2 (Volsk-18, Military Base 61469). Before Russia officially dropped its chemical weapons program in 2017, the facility developed new forms of such weapons, including Novichok nerve agents.

Oleg Tayakin (alias Tarasov)

Oleg Tayakin (alias Tarasov)

Born on December 6, 1980. The leader of the group responsible for Alexei Navalny’s poisoning, he normally coordinated other officers’ actions from the headquarters in Akademika Vargi Street. He served at the Bely Ugol (“White Coal”) base of the FSB Special Assignments Service in Yessentuki and at Aerospace Forces Military Base 03523. After graduating from the Pirogov Medical Academy in Moscow in 2004, he worked as a doctor before joining the FSB Criminalistics Institute.

Alexei Alexandrov (alias Frolov)

Alexei Alexandrov (alias Frolov)

Born on June 16, 1981. Graduated from a medical college in Moscow in 2006, worked in an emergency care unit, and then became a military doctor before joining the FSB in 2013. Alexandrov appears to be the key operative officer, complicit in Navalny’s two poisoning attempts in 2020.

Ivan Osipov (alias Spiridonov)

Ivan Osipov (alias Spiridonov)

Born on August 21, 1976. Doctor of medicine. Took down his social media accounts in 2012, apparently at the time of joining the FSB.

Konstantin Kudryavtsev (alias Sokolov)

Konstantin Kudryavtsev (alias Sokolov)

Born on April 11, 1979. Served at the military base in Shikhany. Graduated from the Marshal Semyon Timoshenko NBC Protection Military Academy before joining the Criminalistics Institute.

Alexei Krivoshchekov

Alexei Krivoshchekov

Born on April 11, 1979. Served at the Ministry of Defense before joining the FSB in 2008.

Mikhail Shvets (alias Stepanov)

Mikhail Shvets (alias Stepanov)

Born on May 3, 1977. His official place of residence is 116 Trubetskaya Street in Balashikha, which matches the address of the FSB’s Special Operations Center. To remind you, it was there, at the special ops center in Balashikha, that Vadim Krasikov (alias Sokolov) trained shortly before setting out to Germany, where he killed refugee Zelimkhan Khangoshvili in August 2019. Phone metadata suggests that Shvets divides his working hours between the lab in Akamedika Vargi Street and the special ops center.

Vladimir Panyaev

Vladimir Panyaev

Born on November 25, 1980, in Serdobsk, Penza Region. Before joining the Criminalistics Institute, he worked at the FSB’s border control service and co-founded a gas equipment company. Incidentally, he lives in the same apartment block as Navalny. After the poisoning, his residential address was changed to the FSB’s headquarters, 1 Lubyanka Street.

37 “Coincidences”: How the poisoners spied on Navalny

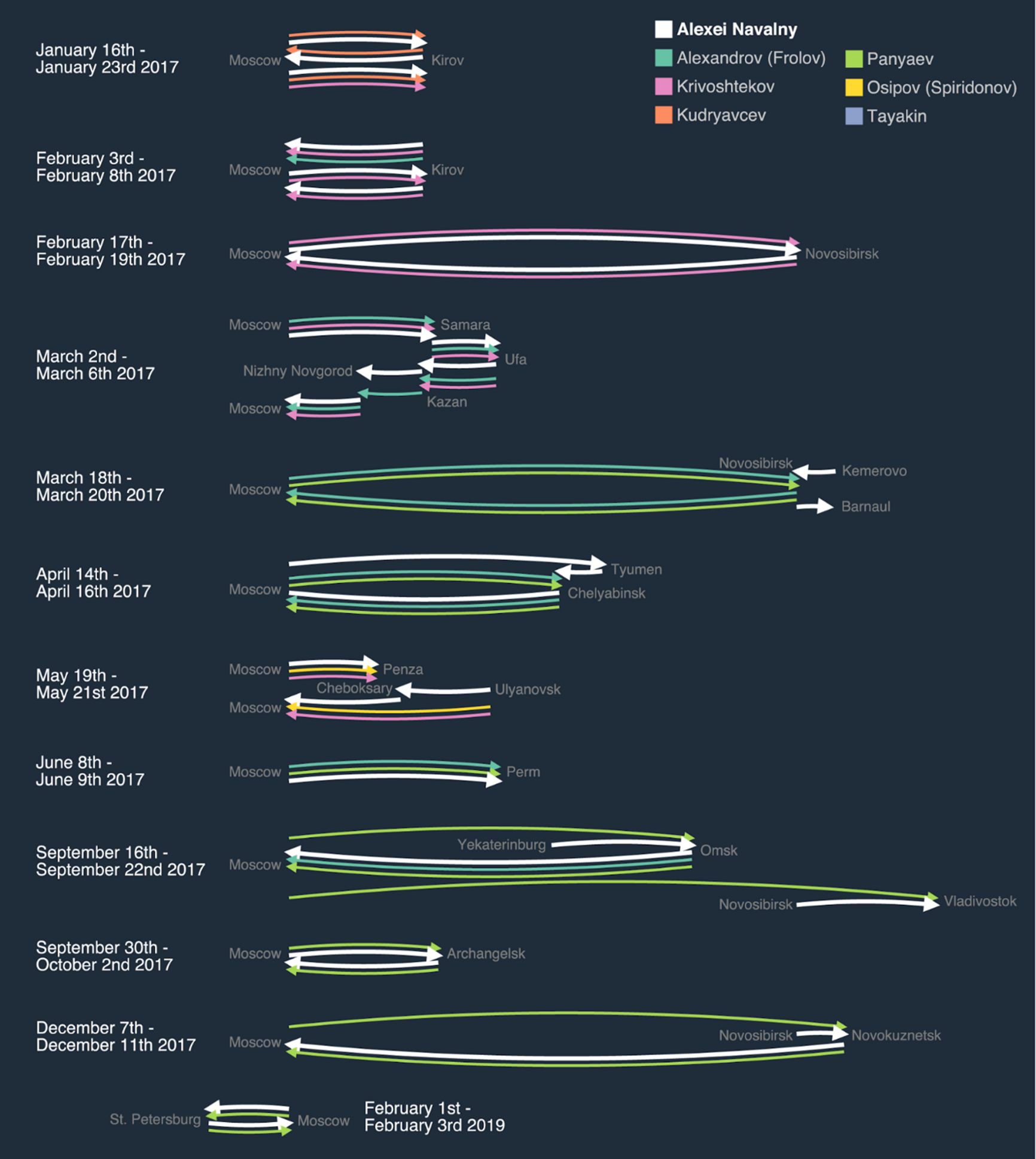

The group members’ earlier travel data suggests that they started following Alexei Navalny at least as early as in January 2017 – immediately after he announced his plans to run for president in the 2018 elections. As part of his 2017 election campaign, Navalny made over 20 trips outside Moscow. FSB poisoners were on his trail almost on every trip except a handful of one-day outings that did not involve an overnight stay. In all, the FSB officers made 47 trips along the same routes as Alexei Navalny, by plane or train.

They usually traveled in groups of two or three, taking separate flights and switching between real names and aliases: at times, they even left Moscow under one name and returned under the other. Notably, they never shared a flight with the opposition politician but picked parallel flights from other Moscow airports. They often booked flights to arrive at Navalny’s destination one day before the politician. Such a modus operandi decreased the risk that Navalny or his team would notice the same passengers sharing multiple flights with them.

In fact, of all the trips made by the FSB crew in 2017, only one didn’t match Navalny’s routes. On April 27, 2017, officers Alexei Alexandrov (under his alias Frolov) and Vladimir Panyaev (under his real name) flew from Moscow to Astrakhan in the Russian south and returned two days later, on April 29, 2017. Navalny did not go to Astrakhan. However, as he wrote in his blog on April 28, 2017, he’d bought a ticket and planned to leave for Astrakhan on that same morning to oversee the launch of his campaign office. He had to change his plans because of the inflammation in his eyes caused by the previous day's attack perpetrated by Kremlin provocateur Alexei Kulakov, who’d splashed Navalny’s face with the alcoholic solution of brilliant green (a popular antiseptic) mixed with an unidentified caustic substance. Saving his eyesight required an intervention from Spanish doctors.

Did the FSB group attempt to poison the politician back in 2017, or were they busy preparing for the assassination? In conversation with The Insider, Navalny shared that he’d had symptoms similar to those he’d experienced during the ill-fated flight from Tomsk, although less pronounced, during a flight in 2017 (he failed to remember which one).

One way or another, after the Central Election Commission refused to register Navalny as a presidential candidate in December 2017 (citing his criminal record in the case of Kirovles despite the verdict having been overturned by the European Court of Human Rights), the surveillance was lifted. In 2018, Navalny's poisoners didn't follow him on any trips, and in 2019, there was only a single trip to St. Petersburg in February. In July 2019, Navalny felt sick in pre-trial detention, where he’d been put for inciting protests. The politician was hospitalized with extreme face swelling and was officially diagnosed with an “allergic reaction”, despite having no record of allergies or opportunity for contact with any allergens in his cell.

In 2020, the hunt for Navalny resumed in full force.

The Kaliningrad fiasco

Phone billing records show a spike in the interaction between SC Signal employees and three FSB officers two months before Navalny's poisoning in Tomsk.

On July 2, 2020, three poisoners – Alexandrov (alias Frolov), Shvets, and Panyaev booked tickets to Kaliningrad under their real names. Panyaev left on the same night, and Frolov and Shvets followed suit on the morning of July 3. On the same day, Alexei Navalny and his wife Yulia left for a five-day vacation in Kaliningrad at the Schloss Hotel Yantarny on the Baltic shore. Once again, the FSB officers picked a different airport to be less conspicuous: Navalny flew out of Domodedovo, and his poisoners departed from Sheremetevo. Shortly before the flight, all three FSB officers made multiple calls to Colonel Makshakov. In turn, he spoke with his superiors, generals Kirill Vasilyev and Vladimir Bogdanov. All three operatives switched off their regular phones during the trip. However, at least one of them, Alexandrov (alias Frolov) used a burner phone to contact his commanding officer, Makshakov, throughout the operation.

Two hotel employees shared with us on different occasions that on the eve of Navalny’s arrival, “several men in civilian clothes came, spoke to the administration, and visited several rooms for purposes unknown”. The employees thought they were from special services and were installing bugs. Unfortunately, both employees had caught only a glimpse of the visitors and failed to identify them in the photos.

On July 3, Alexandrov and Makshakov exchanged several texts from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m. Moscow time and once more after midnight. On July 4, they communicated even more, sending as many as 21 texts throughout the day. The last came in at 4:57 a.m. on the night of July 5 (3:57 a.m. in Kaliningrad). At 4:55 p.m. on July 5, the trio left for Moscow. Upon arrival, Alexandrov called Makshakov, and the three officers headed straight for the office in Akademika Vargi Street.

On the following day, July 6, the events in Kaliningrad and Moscow unfolded in parallel.

Early in the morning on the fourth day of their Kaliningrad getaway, Alexei and Yulia Navalny were planning a long seaside stroll. Having fetched a few things from their hotel room, they were walking to a nearby beach restaurant to get some breakfast, when Yulia Navalnaya suddenly felt unwell.

“I was walking along the street, feeling perfectly fine. Suddenly I was sick. Then it got much worse. Then I felt sicker than I’d ever felt in my life. Alexei kept asking what exactly hurt and how he could help. But I didn’t feel any specific kind of pain and was completely disoriented. He got me some water, and I went back to the room. I sat down on a bench for a bit and then could barely get up. I barely made it to the room, although it was only in 300 meters or so. I lay down. It was terrible. I felt better in an hour and fell asleep. In the morning, I felt completely fine again.”

Navalny looks back on the incident with anxiety: “Imagine someone telling you: ‘I feel terrible, like I’m about to die.’ You start asking: ‘What hurts? Is it your heart? Should I call an ambulance?’ But they answer: ‘Nothing hurts.’ Today, after I’ve been through it myself, I understand how sick you can feel and how you can struggle to verbalize what’s happening to you. Back then, I thought: ‘Oh, it’s nothing. Just her body acting up.’”

The fact that Yulia Navalnaya survived and didn’t even lose consciousness does not signify that the poisoning was mild. By expert estimates, Novichok nerve agents may not cause severe symptoms until the acetylcholinesterase inhibition level reaches 75–80%. That is, if the victim is exposed to a dose that’s not quite lethal, the effects may be limited to temporary motor or respiratory issues.

Meanwhile, Moscow saw a spike in phone communications. Starting from 8:30 a.m. on July 6, 2020, the three poisoners who’d returned from Kaliningrad were making multiple calls to their chief, Makshakov, who relayed their reports to generals Vasilyev and Bogdanov. At 9 a.m., Makshakov, Vasilyev, and Bogdanov made separate calls to Artur Zhirov, the director of SC Signal. At 10 a.m., Zhirov and then Makshakov called Oleg Demidov, a chemical weapons expert who'd worked at the 33rd Military Institute in Shikhany (the one that specialized in Novichok). Oleg Demidov co-authored several patents related to chemical weapons, including a 2003 patent for a “simulation recipe for training combat activity in the event of chemical contamination”. Formally retiring from the 33rd Institute, he spent several years working at the Dubna Research Institute of Applied Acoustics, which has no apparent ties to chemical weapons but which Tayakin and Alexandrov frequented in May and June 2020, judging by their phone metadata. In 2019, Demidov worked at the SC Signal and frequently called at least five members of the FSB poisoning brigade.

Following the numerous phone exchanges between the FSB and SC Signal, General Bogdanov left for the airport at 1 p.m. to catch the 2:30 p.m. flight to Kaliningrad. Geolocation data suggests that he spent the following few days at the FSB headquarters in Kaliningrad, communicating mostly with Makshakov, SC Signal chemists, and the Criminalistics Institute. In all appearances, by the time the general flew to Kaliningrad, the FSB was already aware that the assassination attempt had failed and could also have found out that their victim was Yulia Navalnaya and not her husband, but General Bogdanov’s specific objective remains unclear.

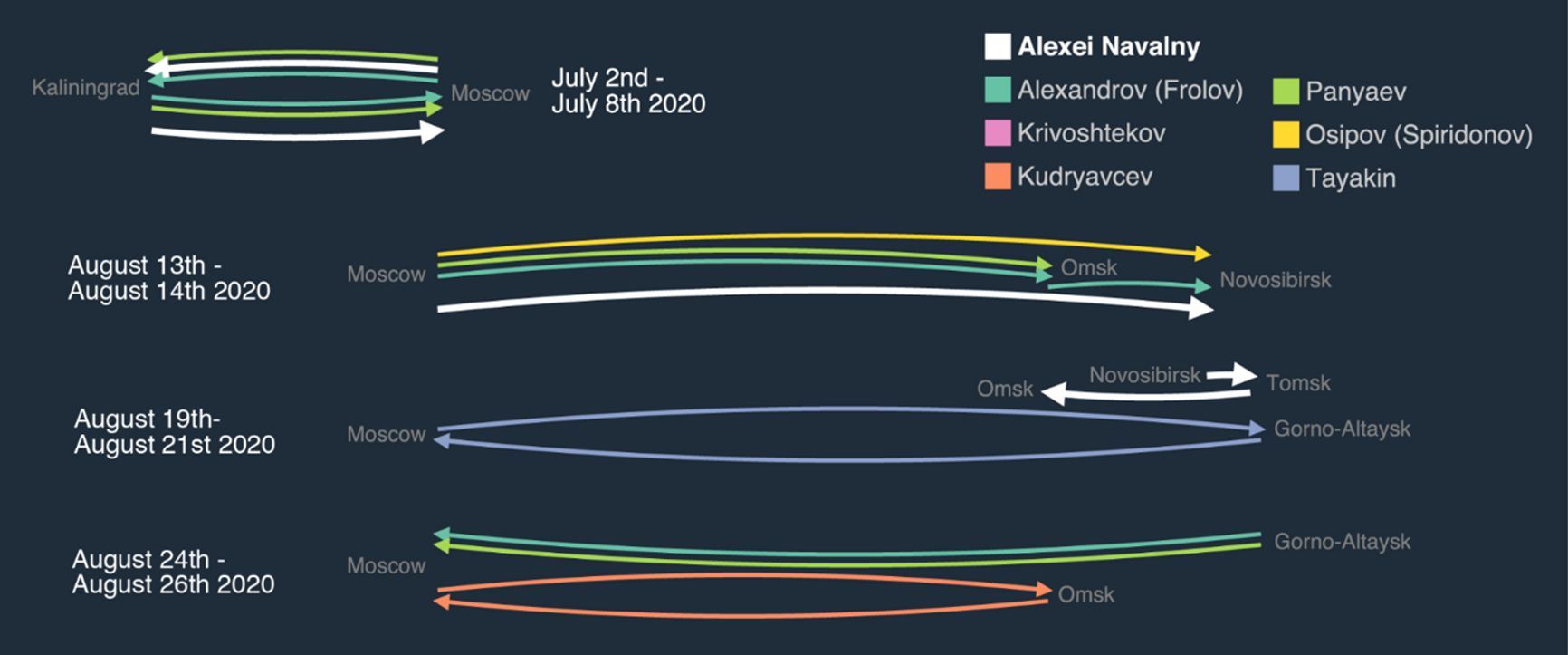

The ultimate attempt

A month after the Kaliningrad fiasco, three FSB poisoners – Alexandrov, Osipov, and Panyaev – booked a flight to Novosibirsk. Alexandrov used his alias, Frolov, Osipov traveled as “Spiridonov”, and Panyaev used his real name. The FSB had already learned that two days prior, Maria Pevchikh, the head of investigations at Navalny's Anti-Corruption Foundation and a key member of his team, had bought a ticket to Novosibirsk. The ACF team had not purchased return tickets, and neither did the FSB. Navalny did not book a return ticket from Tomsk (not Novosibirsk) until August 17, and the FSB officers followed suit just a few minutes later.

Immediately after booking tickets to Novosibirsk, Doctor Ivan Osipov called Makshakov, who called his chief Kirill Vasilyev, the head of the Criminalistics Institute. The same day was also marked by a continuous exchange of phone calls with three other group members: Krivoshchekov, Kudryavtsev, and Shvets.

Judging by the call logs, Tayakin stayed in Moscow and remained in touch with the poisoners who followed Navalny in a messenger app.

When Alexandrov, Osipov, and Panyaev boarded Flight SU-1460 to Novosibirsk departing at 9:05 from Sheremetevo, their colleague Tayakin left the office in Akademika Vargi Street for another Moscow airport, Domodedovo. His phone's geolocation data suggests that he spent quite some time at the airport but made no calls. He stayed there until 11 a.m. and returned to the head office. It was then that Maria Pevchikh, the head of investigations at the ACF, flew out to Novosibirsk from Domodedovo. A few months later, state-owned television channels broadcast footage (both from CCTV cameras and filmed by security agents, judging by the angle) that suggested Pevchikh had been under surveillance all day long, starting from the moment she left her Moscow apartment early in the morning.

On the following day, August 14, 2020, Alexandrov made the first of his two main mistakes at 3:34 p.m. Tomsk time. He briefly switched on his primary phone, causing it to verify geolocation data. At that moment, he was next to the base station at 2 Dimitrova Avenue in Novosibirsk, next to the hotel where Pevchikh had booked a room (however, she was prudent enough to stay at a different hotel).

Phone conversation records from the following three days show that Oleg Tayakin was permanently present at the head office in Akademika Vargi Street in Moscow throughout the operation and only went home for two brief periods. Most nights he was busy accepting and placing online audio calls. He also called Makshakov early in the morning every day. In turn, Makshakov updated General Bogdanov after Tayakin's every call.

Since the three poisoners who’d followed Navalny to Novosibirsk were using burner phones, it's hard to trace their movements (except in the case of Alexandrov's mistake), but the call logs of other unit members, who used their regular phones, suggest two spikes in their activity: on the evening of August 16 and on the night of August 20, 2020. The two periods were marked by a sharp increase in the frequency of calls and included late-night conversations between Makshakov and his bosses on the one hand and Tayakin, Kudryavtsev, and Krivoshchekov, on the other.

The first spike, August 16, coincided with Navalny’s last day in Novosibirsk. On the following day, he and his team drove to Tomsk, which is three and a half hours by car to the north. From 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. Novosibirsk time (3-5 a.m. Moscow time), General Bogdanov and Makshakov were exchanging phone calls. In parallel, Makshakov was texting the poisoners: Shvets and Krivoshchekov. The poisoners may have initially planned to go through with the assassination in Novosibirsk, but the politician's departure for Tomsk threw a wrench into their works.

The other spike in night-time activity occurred late on August 19 and on the night of August 20 – apparently, around the exact time of Navalny’s poisoning in Tomsk.

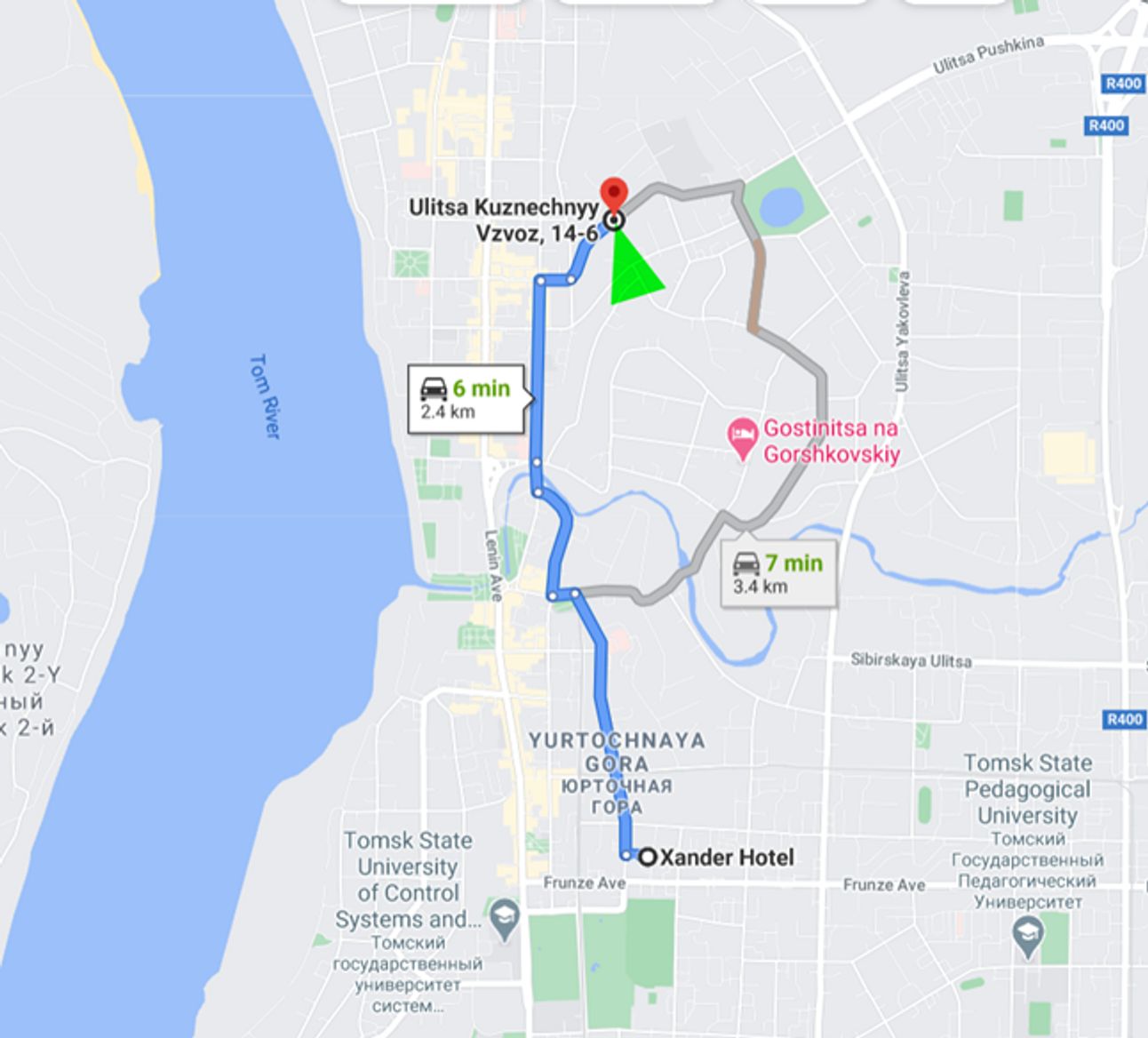

At 4:21 p.m. Moscow time (9:21 p.m. in Tomsk), Vladimir Panyaev texted Makshakov. Around the same time, Navalny went for a dip in the local river (a tradition he liked to observe during his trips to Russia’s regions). He spent two and a half hours away from the hotel. Returning to Xander at 11 p.m., he met with his team, who’d just finished dinner at the hotel's Velvet Bar. After a few minutes at the bar, the politician went to his room. Around the same time, at 8:08 p.m. Moscow time, Krivoshchekov called Makshakov. At 8:37 p.m. Tayakin briefly chatted with someone in a messenger and then called Makshakov, keeping the data transfer line open. In the next few minutes, he made four calls to Makshakov, with the last call starting at 8:44 p.m. (0:44 in Tomsk).

Four minutes later, at 0:48, Alexandrov made his second mistake. He switched on his regular phone again. It was only on for a couple of seconds, but more than enough for the device to exchange a byte of data with the cellular network. According to the metadata, the phone was located close to the cell tower in the center of Tomsk, a few minutes by car to the north of Xander. The map below shows triangulation data and the location of the device to the north of Navalny’s hotel on the night of his poisoning.

The data does not provide a definitive answer to the question of how the poison was applied but matches The Insider’s earlier hypothesis of the Novichok being applied to the politician's underwear, which he’d left at the dry-cleaner's: his clothes were returned while he was away swimming in the river.

Tying up loose ends

At 6 a.m. on August 20, 2020, Navalny’s team gathered in the lobby, waiting for him to come down from his room to leave for the airport with his press secretary, Kira Yarmysh. They’d ordered a taxi. Navalny came down at 6:05. At that very moment (2:05 Moscow time), Krivoshchekov texted Makshakov in Moscow. Makshakov texted Tayakin, and the latter headed for the office immediately. He reached the building in Akademika Vargi Street at around 4 a.m., exactly when Navalny’s flight departed from Tomsk.

The rest is history: 30 or so minutes into the flight, Navalny felt unwell and headed for the toilet to wash his face but didn't feel any better. After leaving the toilet, he only had time to tell the flight attendant that he felt sick and had been poisoned, and then lost consciousness. The pilot headed for the nearest airport, which was Omsk, at around 5:15 a.m. Moscow time, and after a brief delay caused by a false mining alert at the airport, managed to land the plane at 6 a.m. Moscow time. Assessing Navalny's symptoms, the paramedics injected him with atropine (the German doctors would later say it saved his life).

At 6 o’clock sharp, as soon as the plane touched down, Makshakov called Krivoshchekov, and at 7:11 a.m., Major General Bogdanov.

Meanwhile, Tayakin left the office at 5:36 a.m. and headed for Domodedovo Airport. His phone data suggest that he almost made it to the airport at 6:27 or so but stopped a few kilometers away. He placed a call, waited for another half an hour, and headed back to the office, where he continued to exchange calls with Makshakov and other team members. At 11:30 a.m., he arrived at Bogdanov’s office at 12 Vernadskogo Avenue. He spent an hour there and returned to Akademika Vargi Street. Immediately after the meeting, he booked a flight to Gorno-Altaysk to leave on the same day. En route to Domodedovo, he phoned the head of the local FSB division. Flying out at 2:40 a.m., he headed straight to the FSB directorate in the city center upon arrival.

What could Tayakin have been doing in Gorno-Altaysk, a town with a population of 60,000 that is nine hours away from Tomsk and 13 hours away from Omsk? His real destination may have been the neighboring town of Biysk, home to the Institute for the Problems of Chemical and Energetic Technologies, which has special ties to the Criminalistics Institute. According to public procurement data, the institute had provided the NII-2 “the services of producing pharmacological substances” and “research and experimental services in the area of chemistry”. In 2018, the institute also announced the invention of “a nano-adsorbent kit for the removal of chemical weapons traces from contaminated areas”. Importantly, phone logs suggest that at least one of the FSB officers, Alexandrov, remains in close touch with an institute researcher, Mikhail Vasilishin, a chemical engineer specializing in experimental chemical production.

Alexandrov, Osipov, and Panyaev headed for Gorno-Altaysk too. Most likely, it was there that they got rid of the objects that could still bear traces of Novichok. On August 24, all three of them left Gorno-Altaysk for Moscow.

On August 25, 2020, their colleague Kudryavtsev, a qualified chemical weapons expert, flew in the opposite direction: from Moscow to Omsk. He spent less than ten hours at his destination and returned to Moscow on the same night. By then, Navalny was already in Germany, but his clothes (with traces of Novichok) remained at the Omsk hospital, and Kudryavtsev must have come to get them. The Russian authorities are still refusing to provide Navalny with any information regarding the whereabouts of his clothes or the reason for withholding them considering that the poisoning never officially took place.

Notably, there is no data to suggest any of the poisoners were in Omsk when Navalny was hospitalized. Therefore, the rumor that the FSB officers may have tried to poison him once again in Omsk, as The Times speculated, is most likely ungrounded.