Evan Gershkovich, a journalist for The Wall Street Journal, was detained by the FSB in Yekaterinburg on March 30, on charges of collecting state secrets. The journalist had been under surveillance before his arrest. It is expected that his detainment will contribute to Putin's “exchange fund,” which is used to secure the return of Russian spies who have been arrested. This practice of taking foreign hostages for the purpose of later exchange has been adopted by Putin for quite some time. There have been previous instances of such exchanges, such as the arrest of four Qatari athletes by the FSB in response to the detention of two GRU officers in Doha on suspicion of murdering Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev. Another example is the exchange of arms dealer Viktor Bout for American basketball player Brittney Griner. The Insider has found out that Bout was originally supposed to be exchanged for Kevin Nersesian, a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) representative in Moscow, but he detected the surveillance and left Russia. The Department of Counterintelligence Operations (DCRO) of the FSB is primarily responsible for monitoring foreigners. However, as the documents show, it has not been very successful in catching actual spies.

Content

A drug trafficker for a DEA agent

The spy stone and the hunt for MI6

Cold heart and sticky hands

A drug trafficker for a DEA agent

In December 2022, arms dealer Viktor Bout was released in exchange for American basketball player Brittney Griner, who had been convicted of drug smuggling in Russia. Bout, who was known as the “merchant of death” by the media, had already served 15 years in a U.S. prison. The U.S. Department of Justice's Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) conducted a complex special operation to capture Bout, with their officers posing as members of the Colombian group FARC and luring him from Russia to Thailand. Bout was still awaiting extradition to the U.S. when the Kremlin began seeking ways to release or exchange him, likely due to fears that he would reveal the involvement of high-ranking officials from Moscow and Minsk in illegal arms trading to U.S. investigators.

Viktor Bout in a Thai prison

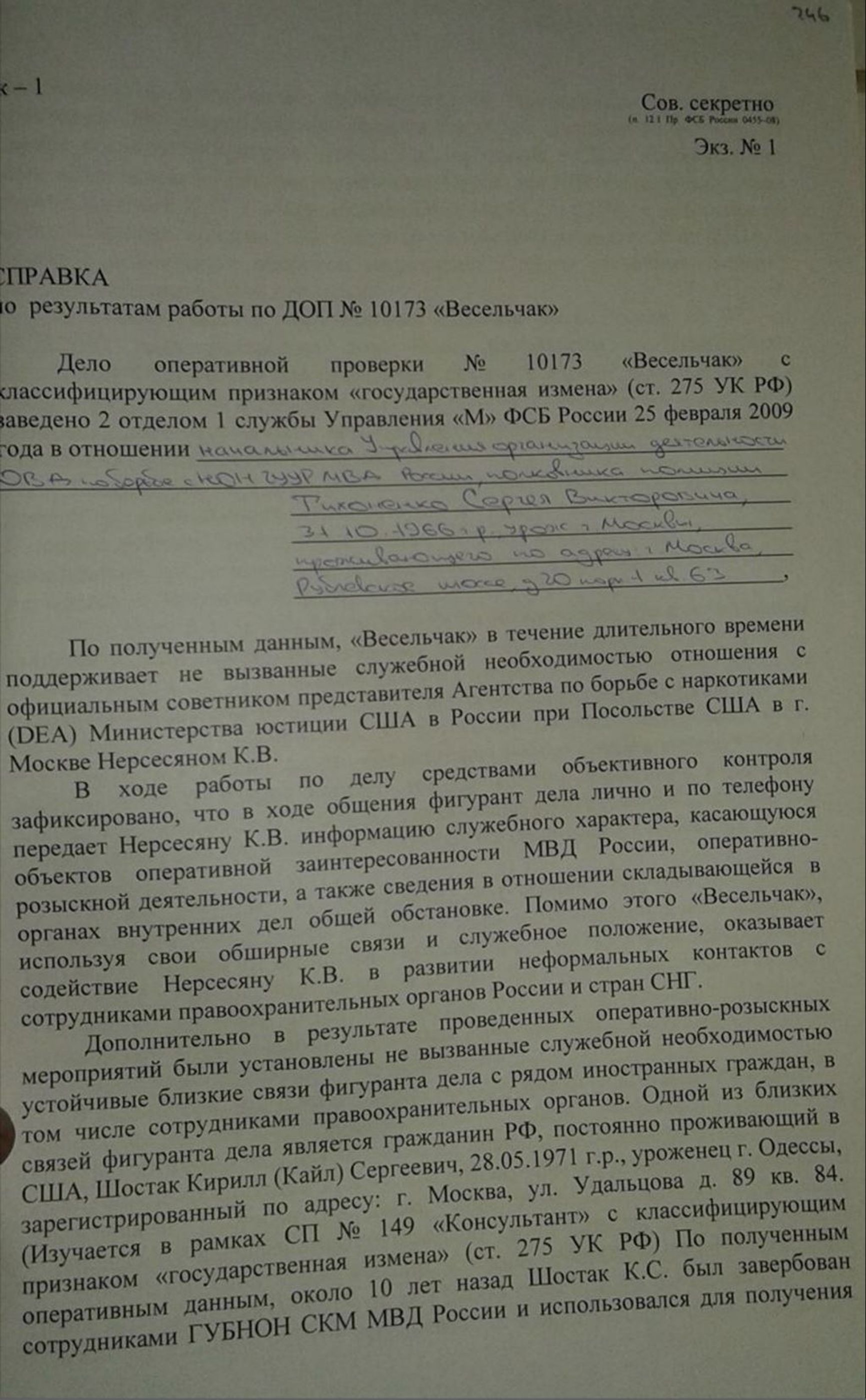

Classified documents from the FSB's DCRO, which were obtained by The Insider, indicate that the Kremlin placed Kevin Nersesian, a DEA agent in Russia, under surveillance while Bout was imprisoned in Bangkok. The Kremlin intended to gather compromising information on the American drug enforcement agent and exchange him for Bout's release after his arrest. Telephone wiretaps revealed that Nersesian had periodic communication with Lieutenant Colonel Dmitriy Abakumov, the head of the 2nd Division of the Operational and Search Bureau (OSB) № 14 of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of the Russian Interior Ministry, as well as with Colonel Sergei Tikhonenko, who leads the Interior Ministry's drug control organization.

The task of monitoring Nersesian was given to Alexander Zhomov, who was then the head of the Federal Security Service's DCRO. Zhomov collaborated with filed surveillance officers from the Operational and Search Directorate (OSD) and Directorate “M”, which oversees the Interior Ministry, Justice Ministry, and Federal Penitentiary Service. General Zhomov was known for his expertise in creating operational scenarios and “setups.” In 1988, he even approached the CIA agent in Moscow, Jack Downing, at the KGB's request and offered his services, successfully deceiving the Americans for two years with a false identity. Additionally, General Zhomov played a key role in exposing Alexander Zaporozhsky, a former deputy head of the Foreign Counterintelligence Directorate of the SVR who was working for the CIA. Zaporozhsky was sentenced to 18 years in prison, then later exchanged for failed Russian spies posing as immigrants in the United States.

FSB General Alexander Zhomov (left)

Abakumov and Tikhonenko, who were in contact with Nersesian, had Operational Review Files (ORFs) opened in respect of them. Abakumov was given the operational code name “Diplomat,” and Tikhonenko was referred to as “Veselchak” [Merrymaker]. Abakumov's ORF suggested that he was providing information on major drug dealers in Russia to the U.S. and aiding in identification of cocaine suppliers from South America. However, later wiretaps revealed that “Diplomat” was actually supplying cocaine to his colleagues in law enforcement, including the head of the Directorate for Combating Money Laundering of the Federal Financial Monitoring Service, known only as R. Additionally, field surveillance officers from the FSB's OSD observed Abakumov entering the U.S. Embassy on the Fourth of July.

ORF “Diplomat”

“Veselchak”'s surveillance also yielded interesting results: “The subject, personally and by telephone, has been transmitting to Nersesian information of an official character concerning persons of operational interest monitored by the Russian Interior Ministry, operational and search activities, as well as information about the general situation within the police system,” an operative from the FSB's Directorate “M” reported.

According to the FSB, it was found that “Veselchak” used a Chase bank card that was supposedly registered under the name of an American businessman of Russian descent, Kirill Shostak, also known as Kyle. Shostak was originally from Odessa and later moved to Moscow, where he studied at the Moscow State University Law School before attending the New York University Stern School of Business. In New York, he founded Navigator Principal Investors, an investment firm that operates in the financial markets of Eastern Europe and South America.

The secret reports suggest that Shostak was already under the FSB's surveillance. Here is a quote from the FSB Directorate “M”'s report:

“According to operational information, approximately a decade ago, K.S. Shostak was recruited by officers of the Main Directorate for Combating Drug Trafficking of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia to gather intelligence on the production and distribution of drugs from Latin American countries into Russia. Throughout this time, Shostak lived in the United States. A few years ago, “Veselchak” arranged a meeting between K.S. Shostak and the US Department of Justice's Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) with the help of Nersesian, after which Shostak allegedly signed a contract with the DEA to assist the US government in its fight against drug trafficking. However, this information requires further verification.”

The Moscow Arbitration Court ruled in 2018 that Ajax Capital LLC, a company led by Shostak, was bankrupt. According to the court documents, the businessman had moved the company's assets and conducted cross-border transactions with securities, which resulted in the bankruptcy.

Despite this, Shostak has appeared as a commentator on Russian state media where he is portrayed as a significant American investor. He often appears in interviews, such as in one with TASS in 2021, where he commented on the possible disconnection of Russian banks from SWIFT. In his comments, Shostak suggested that such measures were not financially rational and were driven by Russophobia and a desire to punish Russia. In another interview, Shostak warned the West of a sharp increase in oil prices if a price cap was imposed on Russian oil products.

The Insider emailed Shostak with questions but hasn't had any response from him.

At this point, Nersesian's detention and exchange for Bout seemed imminent, with the possibility of charging him with espionage. As regards the policemen, they could have been charged with “high treason” and “bribery” under the Russian Criminal Code. The Russian authorities were eager to go ahead with the exchange, but their plans were disrupted when the FBI arrested ten Russian illegals in the U.S., who had been betrayed by Alexander Poteyev, a defector from the Foreign Intelligence Service. In exchange for the failed illegals, four Russian citizens serving time for espionage were released, and Bout was tried and sentenced to 15 years in prison in the U.S.

After being exchanged for basketball player Brittney Griner, Bout became a propaganda tool for the Russian state, portrayed as an innocent victim of American justice. He gave interviews in which he supported the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and Leonid Slutsky, the leader of the LDPR, presented him with a party card in a solemn ceremony.

As The Insider found out, DEA agent Nersesian, after noticing the FSB's surveillance, left Russia, while “Diplomat” and “Veselchak” were fired from the Interior Ministry.

The spy stone and the hunt for MI6

When it comes to real spies, FSB officers often end up with nothing, as the incident with the “spy stone” demonstrated.

The incident that sparked the events depicted in a propaganda film occurred in 2006 when two Wi-Fi receiving devices disguised as ordinary stones were discovered by counterintelligence in two Moscow parks. It was alleged that a Russian agent was using one of these stones to pass on intelligence to MI6. The British managed to remove one of the stones, and the other was featured in Arkady Mamontov's documentary titled “Spies.” “The Russian counterintelligence officers were closely monitoring the activity of foreign intelligence agencies in Russia, and four British so-called diplomats had come under particular scrutiny,” Mamontov narrated, quoting the text written by the FSB. It later became clear that the film was a signal to discredit Russian NGOs that received foreign grants, which of course had nothing to do with the incident involving the stone and MI6.

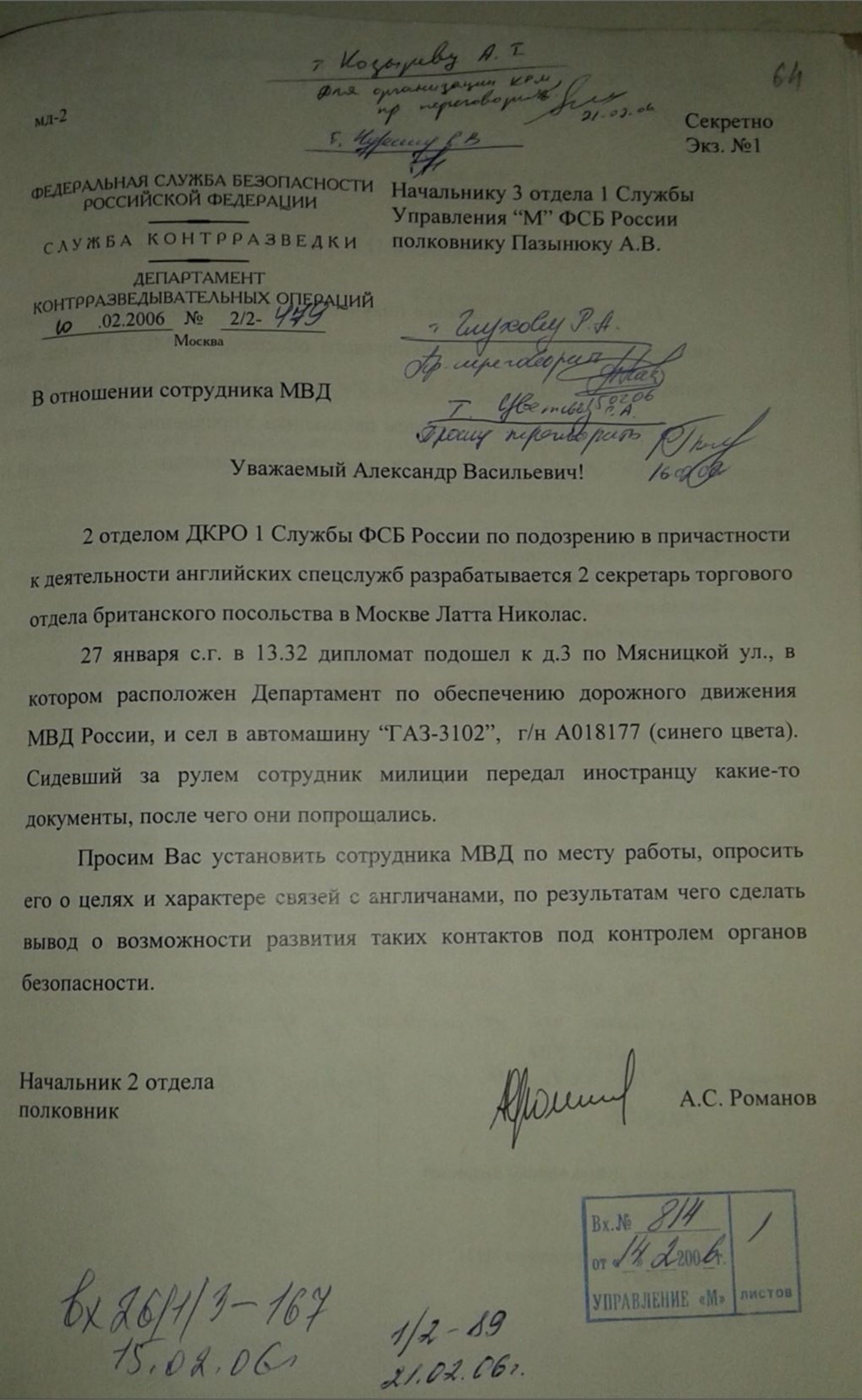

The FSB surveillance team kept a 24-hour surveillance on the second secretary of the British Trade Department in Moscow, Nicholas Latta, due to his connection to the spy stone incident. On January 27, 2006, the team observed Latta near House No. 3 on Myasnitskaya Street getting into a blue Volga car, belonging to the Central Office of the Interior Ministry, and handing the driver some papers. They had a brief conversation before parting ways.

The FSB suspected that diplomat Nicholas Latta may have been working for MI6, and thus his activities were constantly monitored by the “British” department of the FSB's DCRO. Latta's vehicle, a Volkswagen Golf with diplomatic plates, was closely followed by the FSB, and surveillance teams were posted 24/7 outside his apartment on Sadovaya-Samotechnaya Street. Even Latta's wife Susanna, who worked for a charity organization in Moscow, Action for Russia's Children, was under constant surveillance, suggesting that the FSB believed she may have been involved in espionage activities as well.

The discovery of a British “mole” within the Interior Ministry and the subsequent arrest of diplomat Latta held the promise of significant opportunities for the FSB's DCRO. A successful operation would have likely resulted in promotions and rewards for all involved. Furthermore, Nikolai Patrushev, the FSB Director at the time, was seeking to increase the agency's budget and had called for high-profile arrests of foreign intelligence agents.

However, the fact that Ruslan Nurgaliyev, a Chekist from the Patrushev clan, was at the time the head of the Interior Ministry, added some spice to the situation. And in the event of publicity, a scandal could hardly have been avoided.

The DCRO immediately sent a secret request to the FSB's Directorate “M”, which supervised the Ministry of Internal Affairs:

“We ask you to identify the employee of the Interior Ministry at his place of work, to question him about the purpose and nature of his contacts with the British, based on the results of which you can draw a conclusion about the possibility of developing such contacts under the control of the security organs.”

The search for the Interior Ministry employee who was assigned the official Volga began in utmost secrecy. However, it proved to be a challenging task due to the chaotic work environment in the Ministry's special garage. It was discovered that the car had previously been used by Valery Nesterov, the deputy head of the CID, who was in the process of being dismissed. Consequently, the car was reclassified as a “family car” and taken by other employees, primarily for personal errands such as trips to markets, stores, or country houses. After much difficulty, the drivers were identified as freelancers Vladimir Belenkov and Alexander Istratov, both of whom were then secretly interviewed.

“During the interview, Belenkov appeared somewhat hesitant, possibly due to the security agency's keen interest. However, based on the tone and substance of his responses to the operative's questions, it can be inferred that Belenkov was aware of the objectives of the security agencies and the potential adverse repercussions of providing biased or incomplete answers. As a result of the interview, Belenkov agreed to maintain the confidentiality, and the operative provided him with instructions on how to respond to potential inquiries from Belenkov's superiors or colleagues,” an officer of the FSB's Department “M” reported.

The other driver, Istratov, was also interviewed:

“In the course of the interview, Istratov claimed that he had no relatives abroad. Nevertheless, he had worked as a driver in Thessaloniki, Greece, from spring 1996 to March 1997 under a contract with Zagrangaz. Istratov maintained that he had no connections with British diplomats and had not delivered any packages to foreigners.”

In the meantime, both drivers disclosed that the car had been frequently utilized by Elena Zarembinskaya, who was the deputy head of the Directorate “R” within the CID of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Subsequently, Zarembinskaya was put under surveillance and her phone lines were tapped. However, no incriminating information was obtained, and Zarembinskaya vehemently denied any affiliation with British intelligence when questioned by the FSB. The quest for the “mole” within the Interior Ministry reached a dead end.

However, the repercussions for Zarembinskaya did not conclude with the investigation. Her security clearance was revoked, and she was transferred from the CID to the FSIN, where she was appointed to a less important position as the head of the Directorate for organizing non-custodial punishments. Zarembinskaya's tenure at the FSIN was brief. In 2013, her son Sergei Grigorchuk and Roman Zhigaylo, a member of the FSIN special forces detachment, were caught cultivating a marijuana plantation on a garden plot outside Moscow. Additionally, her son had previously been apprehended for possession of heroin. Attempts to contain the scandal failed, and both drug traffickers were handed ten-year prison terms. Following these events, Zarembinskaya was compelled to retire by Putin's decree No. 552.

Presently, Zarembinskaya is a board member of the Officers of Russia non-governmental organization, which is known for actively advocating Russia's aggression against Ukraine and initiatives to rename Volgograd to Stalingrad. Recently, the Officers of Russia bestowed a commendation upon Serbian mercenary Dejan Beric, who was fighting in the DNR. During the event, Zarembinskaya presented him with a banner and hailed him as a “real hero” and an “example for the younger generation to follow,” with a quaver in her voice.

General Zarembinska presents the banner to Serbian mercenary Dejan Beric

Regarding diplomat Nicholas Latta, he stayed in Moscow for another three years before serving as an advisor to the British Embassy in Libya and Iraq. Currently, Latta is involved in energy projects in South Africa. The Insider attempted to contact Latta by sending him questions through WhatsApp, inquiring about his meeting on Myasnitskaya Street and the papers he handed to the driver of the police Volga. Although Latta read the questions, he did not provide any answers. It is possible that Latta is actually affiliated with the intelligence service, and that the FSB failed to identify a spy within the Interior Ministry.

Nicholas Latta in South Africa

Cold heart and sticky hands

The FSB's DCRO not only monitors Western embassies, but also oversees the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other foreign economic organizations. Its staff members are deployed to various departments within the Foreign Ministry as well as the central office of Rossotrudnichestvo.

The DCRO is also responsible for overseeing the private security companies that guard the buildings of the Russian Foreign Ministry and foreign missions. In 2017, two colonels, Alexei Kuternin and Alexei Kostenkov, from the 13th Division of the DCRO were detained for allegedly extorting 1.3 million rubles ($16,000) from Gleb Snitserov, the owner of the private security company Otryad-1. They had promised to assist Snitserov in securing a contract for the protection of the building of the Main Directorate for Servicing the Diplomatic Corps of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. During the trial, Snitserov stated that he had no claims against the counterintelligence officers; taking into account the positive feedback from the defendants' place of service, Kuternin was sentenced to two years in prison while Kostenkov received a sentence of one year and three months.

In 2019, Alexei Komkov, who previously served as the head of the FSB's Internal Security Directorate, became the head of the DCRO. According to a source at Lubyanka, “Alexei Viktorovich was tasked with eliminating corruption within the DCRO, and he was initially doing a great job. However, after the start of the military operation in Ukraine, the department's work was almost fully curtailed.”