Although Vladimir Putin's official biography paints a portrait of a heroic spy in East Germany, in reality his main tasks with the KGB related to political investigations, searches, and jailing dissidents in Leningrad. How is it that after the transition of power, Putin and his KGB colleagues not only stayed free, but made successful careers in the “new” democratic Russia of the 1990s? The nature of that success is explained by Alexander Cherkasov, the chair of the human rights center Memorial, which won 2022 Nobel Peace Prize, along with the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties and Belarusian activist Ales Bialiatski.

Content

A man with an inconspicuous face

The lesser of endless evils

The beginning of a beautiful friendship

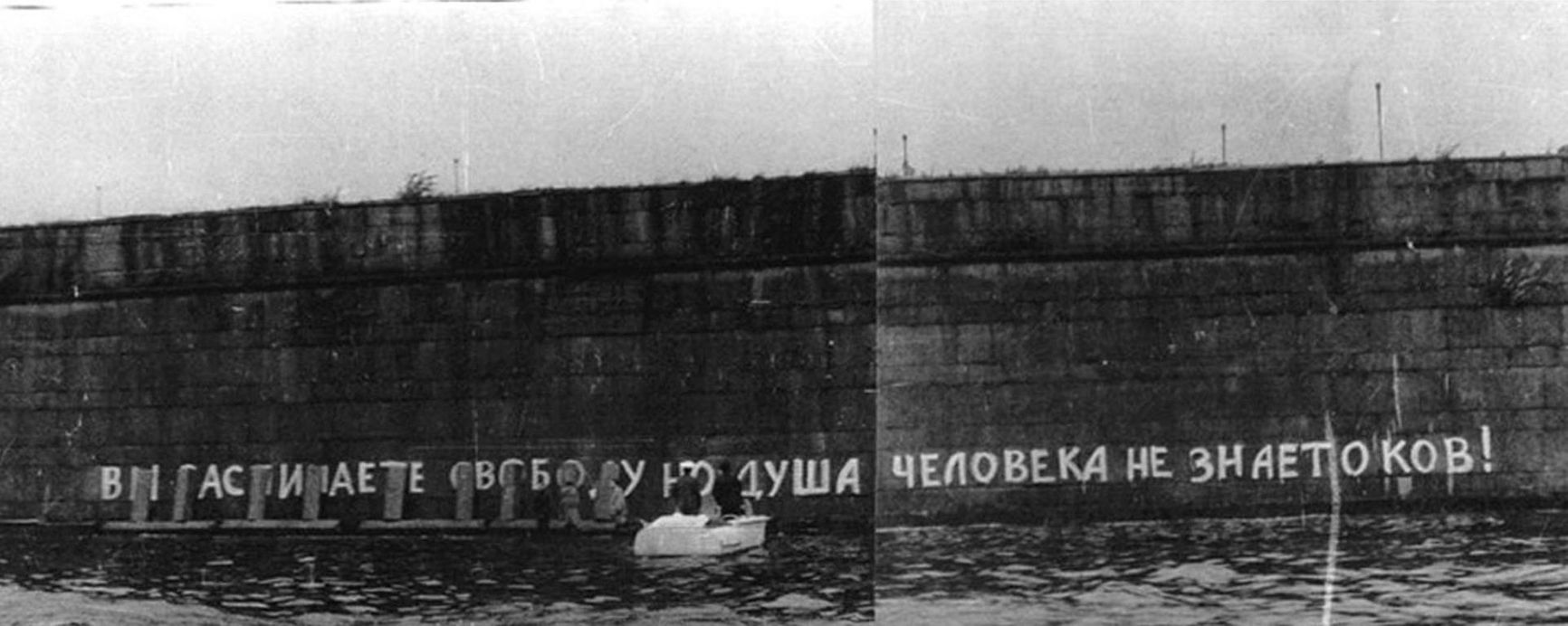

This fall, historian Konstantin Sholmov discovered the name of a KGB officer – Lieutenant Putin – in a search report related to the famous 1976 case for the inscription “You may crucify freedom, but the human soul knows no shackles!” on the wall of the bastion of the Czar's Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg (the original report is kept in Russia’s Museum of Political History). It turned out that Russia's future president worked on the case of artist and activist Yuly Rybakov, who, together with Oleg Volkov, made the inscription. 23-year-old Putin took part in a search of Volkov’s residence.

Vladimir Putin’s involvement in the “inscription case” once more brought attention to his first line of employment.

Prior to that, in 1972-1974, there was the story of an underground collection of poems by Joseph Brodsky, who had recently left his homeland. At first, Vladimir Maramzin assembled folders and volumes from individual sheets left by friends. The KGB then launched an unsuccessful hunt for that collection. One of those who prepared the poems for publication, Mikhail Heifetz, who only wrote a foreword, was still accused of “anti-Soviet agitation” and sent to prison for four years followed by two years in exile (even though the collection of poems itself was never published).

Later, in a conversation with The Insider, Heifetz recalled:

“At one of the interrogations, a young man came into my investigator V. Karabanov's office, and silently gave him some paper, the latter nodded, and the young man sat in the corner without saying a word, just carefully listening to everything. That was it. I’d never have remembered him in my life, but I’d met him before: my wife is a music teacher, she had a favorite student, her name was Natasha Zueva, and once I saw her walking along Kosmonavtov Street with a young man, half-embraced. I liked the girl, and, of course, I was wondering who her companion was, who was the chosen one (we, teachers, have a special weakness for our favorite students). And then I saw him in the office –and I was upset: “Natasha chose a [KGB officer]! Many years went by, and suddenly on the TV screen I saw the new Russian Prime Minister. I see a familiar face. Where did I see him before? I started remembering, and then it came to me.”

A man with an inconspicuous face

In 2010, a newly published memoir of Yuli Rybakov's, Moy Vek (“My Century”), contained an image depicting a Democratic Union demonstration near the Kazan Cathedral in Leningrad and the arrest of one of its leaders, local democrat Valery Terekhov (who gave Rybakov the picture) on March 12, 1989. The policemen are led by a handler: the officer has an inconspicuous, but familiar face – “Volodya Stasi,” who, if the official version is to be believed, worked in counterintelligence all his life in and served in East Germany in the 1980s.

The photo was seen by another St. Petersburg dissident, Andrei Reznikov, who immediately remembered Putin’s “inconspicuous face.” Andrei had a lot of “adventures” in the later half of the 1970s, when, together with Arkady Tsurkov and Alexander Skobov, he put together a commune – they made samizdat magazines, they tried to hold an inter-city conference of activists and organized demonstrations.

Andrei Reznikov recounted one such action:

“The demonstration [in front of the Kazan Cathedral] was in December, on the day of the Decembrist uprising – December 14, 1978. And before that, all the supposed participants were jailed under various pretexts. The day before, I went out to get bread at the bakery. Suddenly some woman started squealing: ‘He's beating me!’ They jumped on me, started hitting me and threw me to the ground. Then I saw the picture I recognized him from – he [Putin] was such a small man. There was a margin of error, but the likelihood was still quite high. And then – he himself admitted in various interviews how they stopped that demonstration. This story [about the December 1978 demonstration] is better read in Putin's memoirs. He wrote, as far as I remember, about the following: when the KGB learned about it, on this day there was a solemn laying of wreaths on the monument by foreign ambassadors. The square was cordoned off, the ambassadors laid flowers, no one was allowed behind the cordon. These are exactly the same methods used to prevent modern marches. <...>

There were two such episodes. When [they arrested us] with Putin, [the arrests] were clean and smooth. And when Putin wasn’t there – the second time – it was a complete mess. My wife and I were attacked and beaten. I was fending [the police] off with sticks and people jumped out of their houses as it was late at night. People wanted to help, my wife started shouting, ‘Help, they're beating me!’ The locals jumped out to help. Then she said it was the KGB. And then everyone left right away.”

This second provocation – the one without Putin – was arranged deliberately, with meaning and intent. Skobov had already been incarcerated in a “mental institution,” but Tsurkov was going to be jailed on serious charges, under Article 70 of the Soviet Criminal Code (“anti-Soviet propaganda”). On the eve of the trial, Andrei was set up as part of another street raid and locked up in a holding cell. Due to his arrest, Reznikov couldn’t be present at his friend’s trial, who was sentenced to 6 years in prison and 3 years in exile.

Current Events Chronicle, Issue 53, Tsurkov and Skobov’s trial

On the night of March 30 to 31 [1979], when Andrei REZNIKOV and his pregnant wife, Irina FEDOROVA, were walking down the street, eight people attacked them. Andrei was beaten. His wife was thrown to the ground.

On March 31, Judge KOTOVICH of the Kuibyshev District People's Court of Leningrad arrested REZNIKOV for 10 days.

The lesser of endless evils

With all this KGB baggage, how on earth did Putin get from the “century of the past” to the “century of the present”? And not just him – how did many of his colleagues manage to navigate the fall of the Soviet Union and come out seemingly unscathed?

When it comes to Putin, at first glance, it’s clear: no one knew about him in general. The “man without features” was nowhere to be seen. He may have ended up at St. Petersburg City Hall not so much by accident, but otherwise unhindered.

Koshelev, listed next to Putin in the search report file, is another matter. Pavel Koshelev, a 1974 graduate of the law department of Leningrad State University (LSU), was better known not by his own name or his involvement in dissident affairs (although he had plenty of those). He was well known under the alias “Pavel Nikolaevich Korshunov”, under he “supervised” the literary “Club-81” and the Leningrad Rock Club on behalf of the KGB. He was promoted to the rank of a colonel or a lieutenant colonel and then rose to become the head of the “fifth service” [a department in charge of counterintelligence in the former Soviet Union] and retired. And then he embarked on an active political career: in 1990, he was elected deputy of the Petrograd District Council and became its chairman. In 1991, he was appointed the head of the district administration. In 1999, Koshelev was appointed first deputy chairman of the Committee on Culture in the city administration. And all this was accompanied by a more or less active discussion of Koshelev-Korshunov’s “political face” – regrettably, without any visible consequences.

These two operatives came to our attention purely by chance – their brethren generally weren’t too visible in investigative reports.

The investigators were a different matter! For example, Victor Cherkesov, who died quite recently. There were cases relating to Christian associations, women's associations, “prevention” (read: pressure), “ordinary dissidents”: Dolinin, Yevdokimov, Meilakh... In the last of the famous cases (the case of “treason” against the St. Petersburg Democratic Union), Viktor Cherkesov was in charge of the investigations department of the KGB’s Leningrad regional department since December 1988. At about the same time, in March 1989, an operative with a familiar but inconspicuous face supervised Valery Terekhov.

Victor Cherkesov and Vladimir Putin

At the beginning of 1992, Cherkesov was appointed head of the Department of the Ministry of Security for St. Petersburg and the Leningrad region. That's when I profiled him in a fact sheet, drawing on a selection of “Chronicle” and other dissident sources in which Cherkesov was mentioned, and sent it to the Human Rights Committee of Russia’s Supreme Soviet. It was a hint of sorts. I wanted to ask them – what’s going on?

To quote the cover note to the brief (original design preserved – The Insider):

“FIRSTLY ... CHERKESOV's predecessor as head of the department was [Sergey] Stepashin, a former police school chief, not knowingly involved in political affairs; it is not the appointment that is alarming here, but the replacement.

SECONDLY... Besides the investigators, so-called “operatives” took part in persecutions of dissidents by the KGB, the latter prevailed in numbers (about 1:10) and carried out the “dirtiest” operations, which aren’t recorded in any official (protocols, etc.) or human rights documents, which serve as the source for this fact sheet <...>.

If one of them is appointed in CHERKESOV’S place, no experts will be able to challenge the appointment without access to the KGB archives. Thus, without solving the problem of ACCESS TO [STATE] ARCHIVES AND LUSTRATION, people previously involved in political repressions will remain and continue to emerge in the leadership of the security agencies and in other key positions...

Compared to the other people mentioned [in this document], CHERKESOV, on the one hand, doesn’t seem to be an accidental figure – we’re dealing with a process here, not an individual case, while on the other hand – he’s not a key figure and isn’t the most terrible [of KGB agents].

...The Russian Ministry of Security is one of the pillars of the current regime. Neither a purge of personnel, nor a handover of archives, has taken place; NATURALLY, neither of these things will actually happen. Appeals for both [a purge and access to archives] at one time “replaced” open criticism of the regime as a whole, and died out after such criticism became possible. Naturally, in the end, the regime changed with the security services remaining intact as its foundation. (The same thing had happened earlier during the TWO changes of power in Georgia – the accession and overthrow of [Zviyad] Gamsakhurdia; apparently, up until the onset of chaos, the process of the security services changing their boss, the latter being tempted to use them for his own ends, in fact becoming their slave, like a “ring of absolute power” – was natural; we were very far from Czechoslovakia [where the state security agencies was dismantled and rebuilt from scratch]. This situation was consolidated by the adoption of the Law on Operative-Investigative Activities and, more recently, the Law on Security... in connection with CHERKESOV’S case, it's worth making it clear that we are once again at the BEGINNING OF THE ROAD.

The second problem facing us is the problem of COMPETENCE. KGB investigators generalkly had a higher legal education and were at least formally supervised by a prosecutor, and they, unlike the “operatives” whose education was usually limited to the KGB school, were almost the only people in the current Ministry of Security who were familiar with the law and had experience acting within the law. It is far from obvious that the replacement of CHERKESOV with another operative from the Interior Ministry would bring a more competent and law-abiding person to that post. In the case of the appointment of an unprofessional “democrat”, it is quite possible that he will lose control over the apparatus (as demonstrated by the cases of Murashov and Savostyanov).

In outlining the issues that arose in connection with the appointment of CHERKESOV, I would like to put [the appointment] in context:

- People not from the system – that is, professionals not involved in the crimes of the totalitarian regime (if one understands professionals as lawyers, not Chekists) should be appointed to key positions in the security apparatus;

- employees of government bodies involved in political repressions should not hold positions in public service outside the Ministry of Security system either;

- in particular, in order for this process to take place within the law, it is necessary to adopt appropriate laws and to solve the problem of KGB archives;

- this is a hopeless case.

Of course, neither the brief or any other references nor conversations had any effect: we couldn’t convince our own friends and colleagues.

The logic of those who made the decision not to “cleanse” the security apparatus is clear. There are former security service departments, which, although former, are now the backbone of the new democratic government. And in the [State] Duma, seated and roaming the streets, are not at all former Communists who have decided to crush this new democratic government. And we have to choose between the two. Who are we fighting? With the former KGB? Or with the “red-brown murderers” [an ideology that bridges fascist and socialist politics]? Either we'll get into a long, pointless, fruitless lawsuit that will lead to lustration (as the experience with the “CPSU case” in the Constitutional Court showed), and in the end we’ll be demolished. Or we postpone the case. For a long time.

In the end, in December 1992, all the “exes” [former KGB agents] who claimed to be the “future” were recertified and re-approved – with no exceptions. They chose between two evils, and that could be called a “political decision” or a “principled position.” There were, of course, many other arguments, but this one was the main one, even if it was kept quiet – the specter of communist revenge and civil war. That’s how the dissident Mikhail Molotov, in the words of his daughter Ekaterina, discussed this dilemma in the Human Rights Committee with the same political prisoners and dissidents of yesterday, the “memorialists.” He returned to analyse the period many times, re-evaluating these decisions.

The beginning of a beautiful friendship

The fact sheet I quoted didn’t touch on one important detail: the agents. One of the most guarded secrets under the old and new regimes, their most sacred item. This is probably why numerous myths are born and survive. For example, they say there was a “sea” of them and that almost everyone was an agent in order to keep an eye on everyone else. In reality, the security services did not at all seek to inflate the agent and intelligence apparatus, rightly fearing a loss of its manageability.

Even though the full-time Chekists [members of Soviet state security] cared a great deal (to be more exact: they were supposed to care) about their agents, about maintaining secrecy and morale (an agent can’t work well when nervous as he will fail himself and ruin the operation), they didn’t greatly respect those who joined the “staff” from the ranks of “agents.” Traitors in general aren’t liked – well, or treated with suspicion, even in those circles. That is why, incidentally, the attitude of the “old guard” of the FSB toward Director Putin was, shall we say, somewhat ambiguous.

The rejection of lustration in Russia in any form meant, among other things, refusing to disclose agents – under plausible pretexts, of course, including the “protection of rights” and a refusal to start a “witch hunt.”

Firstly, people who had worked extensively and sensibly in the relevant archives said that the Chekist reporting on other agents was as false as any Soviet reporting. The “operative files” were the most secretive part of the Chekist case-flow, but they weren’t filled with meaning and truth precisely because of that. Unnecessary details and “bullshit” in agent-on-agent reporting was plentiful: the same applies to the “handlers,” and let’s not forget about good-old human laziness.

Secondly, there are obvious cases, but in general, everything’s complicated. Let’s say someone made a mistake and signed a piece of paper, but didn’t turn anyone in, or then refused to cooperate and generally behaved like a hero, but now, after the publication of the file, his life will be determined by that piece of paper and public opinion.

Thirdly, the ability to read archival and any other documents in general is no less difficult a craft than interpreting X-rays. And so to follow the Chekist card catalogues formally, without studying each individual case, is, in fact, almost to be drawn into their delirium, into their plan and their worldview.

I could continue and develop these arguments into a “Treatise on Snitching” or a “Treatise on Innocence,” but there’s another side to all this.

Without disputing these arguments, I will note one unavoidable and very curious consequence: former agents turned out to be dependent. The agent was forever “on the hook” for his “handler” – especially if in his new life he was a prominent politician, a “democrat,” etc.

Nothing stuck to [Vladimir] Zhirinovsky, it was as if he was made of teflon – he lost his court case in which he challenged the charges of being a KGB agent, and nothing happened. But let's imagine that yesterday's agent is not a cartoon “liberal-democrat,” but an honorable democrat and liberal respected by all. Exposure [as a KGB agent] would mark the end of his career.

And on the other hand, yesterday's handlers are now nobodies – they’re nothing more than useful servants.

You could call this kind of relationship toxic. Or you can quote the movie Casablanca: “I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship!”