Vladimir Putin refuses Ukraine the right to be a full-fledged state. Three days before the Russian invasion, he made yet another attempt to convince his audience that “modern-day Ukraine owes its existence fully and entirely to Bolshevik Russia”. Meanwhile, on March 17, Ukraine celebrated the 105th anniversary of its Central Rada (“Council”), which was established half a year before the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd (the name of Saint Petersburg at the time) as the long-awaited outcome of Ukraine’s national political evolution. Historian Boris Sokolov narrates the formation of Ukraine as a political nation.

Content

The Pereyaslavska Rada: a union of two nations or a takeover?

The Russianization

The Russian Revolution of 1905. Emancipation

The fall of the Rada. The beginning of an end.

The Soviet period. Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Ukrainian Insurgent Army, Stepan Bandera

On March 4 (Gregorian Calendar: March 17), 1917, three days after the victorious February Revolution in Russia, Ukraine’s Central Rada started its work in the Kyiv City Teacher’s House in Volodymyrska Street. The Ukrainians established their first representative body, bringing together political, cultural, professional, and community organizations. Historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky, who would return to Kyiv from exile nine days later, was elected its chairman in absentia. The All-Ukrainian National Congress, which took place on April 6–8 (Gregorian Calendar: 19–21), 1917, elected 115 Rada members. A 20-strong executive body was also formed under the name of the Mala Rada (“Smaller Council”) to share authority with the Russian Provisional Government commissars. Subsequently, the Mala Rada was extended to include fifty-eight members, of whom eighteen represented ethnic minorities, while the Central Rada membership reached 822.

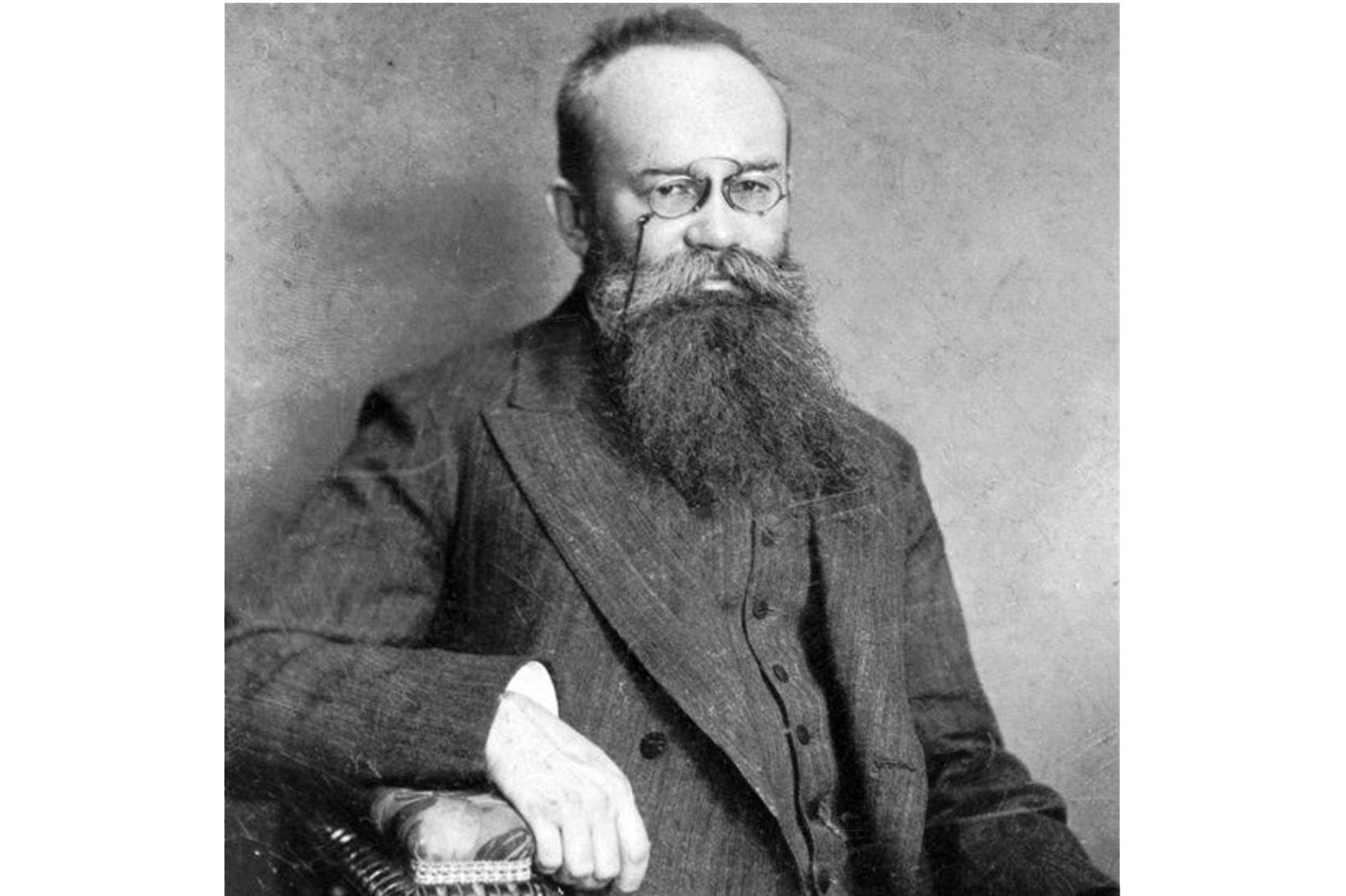

Mykhailo Hrushevsky was elected chairman of the Central Rada in absentia

On June 10 (23), the Central Rada unilaterally declared Ukraine's national and territorial autonomy within Russia and its own status as the supreme legislative body throughout Ukraine. Subsequently, the General Secretariat was established, with writer Volodymyr Vynnychenko at the helm, and became a full-fledged government. After the Bolsheviks came to power in Petrograd as a result of the October Revolution, the Rada took control over Kyiv. The Central Council was mostly comprised of local socialists: the Ukrainian Social Democratic Labor Party, the Ukrainian Socialist Revolutionary Party, the Ukrainian Socialist Party, and a few others.

The Rada’s only non-socialistic party (despite its catchy name) was the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Federalists, who were close to the Russian Constitutional Democrats, widely known as ‘the Kadets’, except on the nationalities problem. Within the Rada, these parties were represented by the All-Ukrainian Peasants’ Deputies Council, the All-Ukrainian Military Deputies Council, and the All-Ukrainian Workers’ Deputies Council. The Central Rada also included representatives of professional, educational, economic, and community associations, as well as organizations and parties of ethnic minorities (Poles, Russians, Moldavians, Germans, Tatars, and Belarusians). The Bolsheviks had considerably less weight in Ukraine than in Russia, so Ukraine escaped the Bolshevization of its Soviets (“Councils”) in August–September 1917. As a result, parties that supported the Central Rada still had the majority. Similarly, the Southwestern and the Romanian fronts in the First World War included a large share of Ukrainians among their personnel and ended up significantly less Bolshevized than the Northern and the Western fronts.

The Bolsheviks had considerably less weight in Ukraine than in Russia, so Ukraine escaped the Bolshevization of its Councils

The Pereyaslavska Rada: a union of two nations or a takeover?

The establishment of the Central Rada was the pinnacle of the Ukrainian national movement, which emerged at the turn of the 20th century, drawing much inspiration from its Polish counterpart. However, the two movements were fundamentally different from the historic, cultural, and religious perspectives. Divided in the late 18th century between Russia, Austria, and Prussia to disappear from the political map of Europe for over a century, the Polish state had nevertheless existed for nine centuries before that. Its well-established statehood fostered a strong culture, which retained its power and momentum for further development even after the state dissolved. The period of Ukraine’s independence was incomparably shorter than Poland’s – if we consider Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s Cossack Hetmanate, also known as the Zaporizhian Host (1648–1653), as such. The Ukrainian nation began its formation in the late 16th century, when Ukrainian lands, formerly governed by Lithuania, became the property of the Polish crown after Poland and Lithuania established a commonwealth, Rzeczpospolita, in 1569.

Aleksey Kivshenko, Pereyaslavska Rada. Watercolor, 1880.

In 1654, the Pereyaslavska Rada (Council) convened, with an outcome that was traditionally interpreted by Soviet historians as the “reunification of Ukraine and Russia”. Notably, while Moscow perceived the reunification as Ukraine's accession to the Tsardom of Russia with a certain degree of autonomy, Khmelnitsky and the Cossack elite envisioned an alliance of two equal states. In reality, however, Moscow’s version prevailed before long. The Hetmanate's true independence only lasted until Hetman Ivan Mazepa's treason in 1708. After that, hetmans largely lost control over the Host, becoming appointees of the Imperial government, until the Hetmanate ceased to exist in 1764. The Ukrainian language was abolished from official documents.

By the late 18th century, the Russian Empire had gained control over most of Ukraine, stripping it of any autonomy. The smaller share of Ukraine’s territory, Eastern Galicia, ended up as part of Austria. The Ukrainian nobility began to undergo rapid Russianization, so the Ukrainians of the mid-19th century Russian Empire were mostly peasants and priests. Unlike the Poles, the Ukrainian nation also suffered from a religious divide. Eastern Galicia was dominated by the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, established by the Union of Brest in 1596. Ukrainians who lived in Right-Bank Ukraine, which belonged to Poland until 1772, were either Eastern Orthodox or Greek Catholic (Uniates), while Left-Bank Ukraine was inhabited almost exclusively by the Orthodox. When the Russian Empire banned the Uniate Church in 1839, almost all Greek Catholics in Ukrainian territories either converted to the Orthodox faith or emigrated to Eastern Galicia under Austrian rule.

The Russianization

The situation in Ukraine was different from Belarus. Most Belarusian Greek Catholics embraced Catholicism and formed a large group that was culturally and politically close to the Poles. After 1839, the Eastern Orthodox faith came to dominate Russia’s Ukrainian territories, which made the assimilation of Ukrainians easier. The Ukrainian language and culture developed more or less freely in the Russian Empire up until the mid-19th century. Alarmed by the emergence of clandestine Ukrainian societies, such as the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, which sought to consolidate Ukrainians as a separate nation, the Russian government restricted the use of the Ukrainian language – even though these movements made no social or political demands.

School textbooks and religious works could no longer be published in Ukrainian from 1863, and Alexander II’s Ems Decree of 1876 prohibited the publication of any Ukrainian-language academic and popular science books or any literature except for “historical documents and literary landmarks” and belles-lettres – but they had to use Russian orthography and pass pre-publication censorship. Special authorization was also required to bring books in Ukrainian to the Russian Empire from abroad and to perform Ukrainian songs at concerts. Local teachers who were suspected of pro-Ukrainian sentiments were transferred to Russian governorates outside Ukraine and replaced by their Russian colleagues.

These measures limited Ukrainians’ opportunities for university education and a career in public service or the military and, as the Russian government assumed, promoted their Russianization. Meanwhile, in the neighboring Eastern Galicia, a province of the Austrian Empire, the Ukrainian language and culture developed more or less freely. It was here that many figures of the Ukrainian national movement received education in their native language. In 1891, Ukrainian writers and ethnographers Borys Hrinchenko, Ivan Lypa, Vitaliy Borovik, and others gathered on poet Taras Shevchenko’s grave and founded the clandestine Brotherhood of Taras, which stood for the reunification of all Ukrainian territories into a single sovereign nation-state.

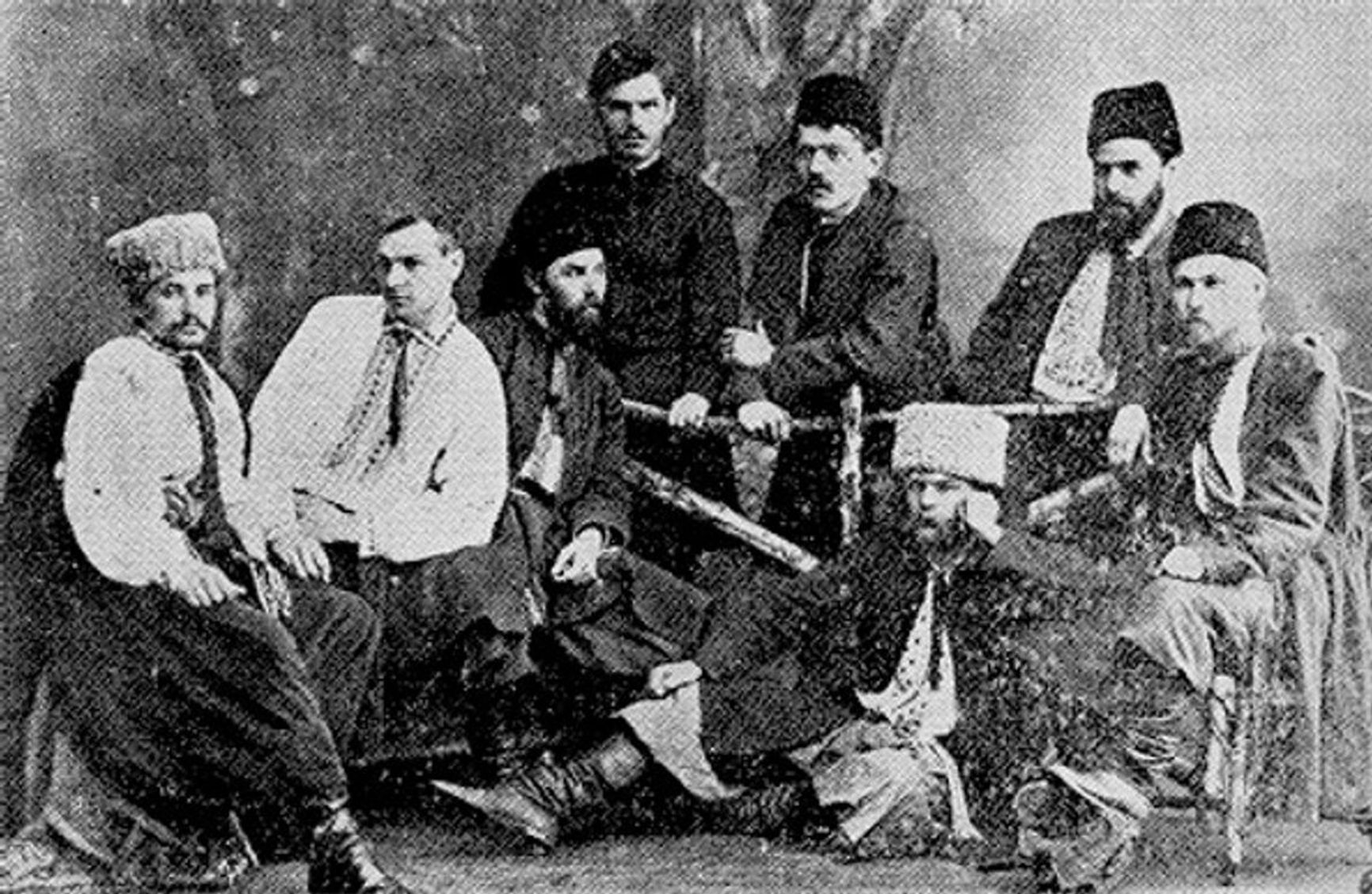

The Brotherhood of Taras, Kharkiv

In 1900, the brotherhood founded the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party. Other Ukrainian parties that emerged at the turn of the century were less radical and promoted Ukraine’s autonomy within the Russian Empire as well as its reunification with the Ukrainian lands of Austria-Hungary. Similarly, most Polish politicians in Russia advocated the autonomy of Russian Poland and its reunification with the Polish territories that belonged to Austria-Hungary and Germany.

The Russian Revolution of 1905. Emancipation

After the Russian Revolution of 1905, publications in Ukrainian were no longer restricted, and Ukrainian parties received the opportunity for legal or semi-legal activity. Leaders of the Ukrainian national movement were mostly writers and scholars: historians, ethnographers, and folklore researchers. By then, very few public officials, military officers, or bourgeoisie representatives were ethnically Ukrainian. The latter were predominantly Russian, Polish, or Jewish. These three ethnic groups also made up most of Ukraine's urban population.

During the First World War, many Ukrainian soldiers – mostly rural intelligentsia and well-off peasants – worked their way up to officer rank, to become the military backing of the Central Rada. By the decision of the First All-Ukrainian Military Convention held in Kyiv in March 1917, the Ukraine-based troop units of the South-Western Front were Ukrainianized. Ukrainian soldiers and officers from other fronts were transferred here, while personnel of other ethnicities was relocated elsewhere. The Provisional Government supported this initiative, hoping it would boost the troops’ fighting capacity and enable the army to hold the front. The Commander of the 1st Ukrainian Corps (formerly the 34th Army Corps) was Lieutenant General Pavlo Skoropadskyi, an indirect descendant of Hetman Ivan Skoropadskyi. The post of the Secretary-General (Minister) for Military Affairs was entrusted to Symon Petliura, a leader of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Labor Party, former envoy of the All-Russian Zemstvo and City Union to the Western Front, and chair of the Ukrainian General Military Committee, which was popular among Ukrainian servicemen.

Symon Petliura

On October 31 (Gregorian Calendar: November 13), 1917, the Rada declared its authority over the governorates of Kherson, Yekaterinoslav (Dnipro), Kharkiv, Kholm, and partially Taurida (Crimea), Kursk, and Voronezh. On November 7 (20), the Ukrainian People’s Republic declared its autonomy within the federative Russian Republic. It also reiterated its loyalty to the Triple Entente and commitment to nationalize land and carry out an agrarian reform to divide landowners’ property, introduce an eight-hour working day, and empower local governments. On January 9, 1918, when the Bolsheviks had seized Kharkiv and were approaching Kyiv, the Rada proclaimed the UPR’s independence. However, the Ukrainianized units could not withstand the onslaught of the Bolsheviks, whose military included most soldiers of the former imperial army. Kyiv surrendered. It became apparent that Ukrainian independence needed external support to survive.

On January 27 (Gregorian Calendar: February 9), 1918, the Central Rada signed a peace treaty with the Central Powers, which acknowledged its independence. German and Austro-Hungarian troops entered Ukraine and banished the Red Army. The UPR’s government pledged to supply Germany and Austria-Hungary with food since their blockade by the Triple Entente had caused their population to starve. Neither the Germans nor the Austrians were happy about the Central Rada’s agrarian reform, which suggested setting up small farmsteads. The occupants believed it would be easier to procure grain from large landowners’ estates.

The fall of the Rada. The beginning of an end.

On April 29, 1918, the Central Rada was deposed with input from German occupation troops and de facto ceased to exist. In its place, Pavlo Skoropadskyi was appointed hetman of all Ukraine. A former general of the Imperial Russian Army and Ukraine's biggest landowner, he had no ties to the country’s national movement and did not speak Ukrainian. Moreover, he started his tenure by rolling back the agrarian reform to restore landowners in their rights, which cost him the support of the masses.

Meanwhile, Germany focused on achieving a compromise peace with the Triple Entente. Berlin realized that Ukraine would be out of Germany's reach after the war regardless of its outcome, so reinforcing the young nation's statehood was not their concern. Hetman Skoropadskyi did not receive approval to create a Ukrainian army because the Germans feared that such an army, headed by former Russian officers, might one day turn against Germany and Austria-Hungary. After Germany's defeat in the First World War and the Austro-Hungarian withdrawal from Ukraine, Skoropadskyi’s regime was easily toppled in December 1918 in an uprising staged by the UPR's Directorate headed by Petliura and Vynnychenko, with the Hetman fleeing to Germany.

On January 22, 1919, the UPR joined forces with the West Ukrainian People's Republic (WUPR), which had been established in November 1918 in Eastern Galicia following Austria-Hungary's capitulation. However, immediately after, the Ukrainian Galician Army based on the Ukrainian Legion of the Austro-Hungarian Army had to take up arms against the restored state of Poland. The UPR provided troops and weapons from Eastern Ukraine, allowing the WUPR to hold out for another six months, after which the whole of Eastern Galicia was occupied by the Polish.

Meanwhile, the UPR's troops failed to deter the Red Army, mainly because of the divide in its administration. Vynnychenko, backed by the majority of the Ukrainian national movement, advocated Ukraine's autonomy within Russia and a deal with the Bolsheviks. They soon left the Directorate, and many Ukrainian troops followed them, siding with the Bolsheviks. Symon Petliura, who became the head ataman (commander in chief) and the head of the Directorate, never managed to restore Ukraine’s independence, unlike Józef Piłsudski, his Polish counterpart. Whereas the Polish national movement had been in place for a century and had earned the Triple Entente’s recognition, the newly emerged Ukrainian movement was not treated seriously. England and France banked on Admiral Alexander Kolchak's and General Anton Denikin's White Armies, which stood for a “single and indivisible” Russia. If the Whites had won, the Triple Entente nations would have offered up Eastern Galicia to Russia’s new government. Without any external support, the UPR's army had to fight against the Red Army, the Poles, and Denikin's army of South Russia all at once. Defeat was inevitable.

For a short while in 1920, during the Polish-Soviet War, Ukraine and Poland were allies. Pilsudski saw an independent Ukraine as the necessary buffer zone between Soviet Russia and Poland. In compensation for Polish assistance, Petliura was forced to cede Eastern Galicia and Volhynia to Poland. However, even though Poland defeated Soviet Russia in the war, the independent Ukrainian state never came to be, as Symon Petliura left the country in late 1920, along with the UPR’s government and army. In 1926, the former head ataman died in Paris at the hands of a terrorist avenging the Jewish pogroms carried out by Ukrainian troops. His killer was suspected of ties to the OGPU (the Soviet security agency and the predecessor of the NKVD and KGB).

The Soviet period. Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Ukrainian Insurgent Army, Stepan Bandera

Established in Europe in 1929, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) sought to build an independent Ukrainian state that would consolidate all Ukrainian lands by any means necessary, up to and including acts of terror. The OUN was popular among Ukrainians living in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania but barely known in Soviet Ukraine. Before the Second World War, the organization split into two factions: Stepan Bandera's (OUN-B) and Andriy Melnyk’s (OUN-M). Both collaborated with Nazi Germany, harboring hopes of Ukrainian statehood after Hitler's victory over the USSR. However, as early as in July 1941, the Germans dispersed the Ukrainian government Bandera’s associates had set up in Lviv, arresting many of its members and Bandera himself. Similarly, they seized many of Melnyk's supporters, and Melnyk ended up in a German concentration camp in 1944. Bandera’s faction, which had a bigger following, continued collaborating with the Nazis, choosing the lesser of two evils, up until 1943, marked by the creation of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). The UPA fought against both the Nazis and the Red Army, with its partisan war against Soviet troops and the Soviet administration dragging out until 1953. In 1956 and 1957, many former UPA fighters who had been serving prison sentences in Siberia returned to Ukraine following an amnesty. This resulted in a restoration of the partisan movement, which was, however, stamped out before long. The UPA operated in Eastern Galicia, Volhynia, Zakarpattia, Northern Bukovina, Southern Bessarabia, and a few adjacent areas on the right bank of the Dnieper, such as Vinnytsia and Kyiv regions. The insurgents did not attempt to go beyond the Dnieper.

The UPA’s partisan war against Soviet troops and the Soviet administration continued until as late as 1953

In the early 1920s, the Bolsheviks, in an effort to win the sympathies of former Central Rada supporters, announced the Ukrainization of Soviet Ukraine. They created conditions favoring the development of its national culture and made Ukrainian the language of bureaucracy and education, both higher and secondary. The project of creating a Ukrainian army was in the works but never came to life. Representatives of the Ukrainian NKID (ministry of foreign affairs) were appointed to Soviet embassies in countries with a Ukrainian diaspora.

The Soviet administration tried to secure cooperation from Volodymyr Vynnychenko, who joined Ukraine's Communist Party and received the post of Deputy Chairman in the Ukrainian government. He was never included in the Party’s Political Bureau, though, and realizing he was being used as a figurehead, he emigrated in late 1920. Former Central Rada Chairman Mykhailo Hrushevsky withdrew from politics as early as spring of 1918, after Skoropadskyi’s coup. Returning to the USSR from emigration in 1924, he went for an academic career and was elected Academician of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. However, Soviet authorities arrested Hrushevsky in 1931 under charges of counter-revolutionary activities. Upon his release, he was exiled to Moscow and banned from ever returning to Ukraine. In 1934, he died from complications of a routine surgery. The NKVD is rumored to have been complicit in his death.

As for the Ukrainization (also dubbed “indigenization”), it came to an end in the early 1930s. Almost none of its authors or drivers survived the Great Purge of 1937–1938. The number of Ukrainian schools dwindled, and government agencies switched back to Russian. Notably, even at the height of Ukrainization, ethnic Ukrainians never occupied the post of the First Secretary (leader) of Ukraine's Communist Party. This happened for the first time in 1953, when Lavrentiy Beria, former head of state security and de-facto head of state after Stalin's death, proposed reinforcing republican authorities with local officials who spoke local languages.

Beria's arrest made the initiative irrelevant, and the trend for Russianization continued in Ukraine, especially in its eastern and central parts. It is crucial to remember, however, that post-WWII Soviet Ukraine also included Eastern Galicia, Volhynia, Northern Bukovina, Southern Bessarabia, and Zakarpattia. The Ukrainian language prevailed across these territories, Russianization was never a success, and former OUN and UPA members had partially maintained their influence.

In the 1970s, Ukraine was home to a rather active dissident movement united under the banners of nation and culture. When Ukraine started its progression towards independence during Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika, it was driven primarily by old-time nationalists picking up the torch of the UPR and OUN, former Ukrainian dissidents, and ex-Communists with a nationalist streak – such as Ukraine’s first president Leonid Kravchuk.

Gained in 1991, Ukraine's independence was not only celebrated by the masses, as confirmed by the referendum in December 1991, but also garnered support from the U.S. and the West at large. Over the 30 years that have elapsed since the declaration, traditional ethnic nationalism has transformed into political nationalism. Today, the overwhelming majority of Ukrainian residents are true patriots of their nation, regardless of their ethnic origins. Many of those fighting Russian aggressors speak Russian as their mother tongue. And this new, universal type of Ukrainian patriotism is a guarantee of Ukraine's resilience in the face of the Russian invasion.