60 years have passed since the Earth's first cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, went into space on board the Vostok spacecraft. At that time the USSR was the leader in astronautics, and competed with the US in the space race. Today the Americans are exploring Mars and planning manned flights to the Moon; China and India are developing their space programs; and yet Russia has not managed to come up with a clear space strategy: every industry player is trying to grab the biggest slice of the pie, contracts are being signed and immediately cancelled, and the lunar program is generally in question.

The United States, Russia, China and India are currently flying or about to fly into space. The European countries, Japan and Canada are not yet ready for space missions of their own; they are participating in international programs. Their astronauts fly to the ISS and plan to participate in the US lunar program Artemis.

In 2011, the US wrapped up the Space Shuttle program. A total of 135 low orbit flights had been performed since April 12, 1981. The orbital shuttles' final missions were connected with the completion of the International Space Station, the fifth mission dealt with servicing the Hubble Space Telescope. From 2011 to 2020, it was Russia's Soyuz spacecraft that were used for all manned flights to the ISS, normally four manned launches per year. But does this mean Russia has retained its leadership in manned space exploration? Let's see.

Russia

From 1967, the USSR used only a single type of manned spacecraft, the Soyuz. Initially, it was built for the secret Soviet lunar program, but it never brought cosmonauts to the Earth's satellite. In the late 1960s, there was a series of unmanned space missions to the Moon under the «Probe» program, but the US moon landing of July 20, 1969 forced the USSR to stop its preparations for sending Soviet cosmonauts to the moon. Soviet cosmonautics switched to building low-orbit manned stations (Salyut, Almaz, Mir), and different variants of the Soyuz spacecraft became the main vehicle for transporting astronauts. Some alternative transportation systems were additionally developed, for example, the transport supply ship (TKS) or the Buran orbital shuttle, but work on them was curtailed, primarily due to economic reasons.

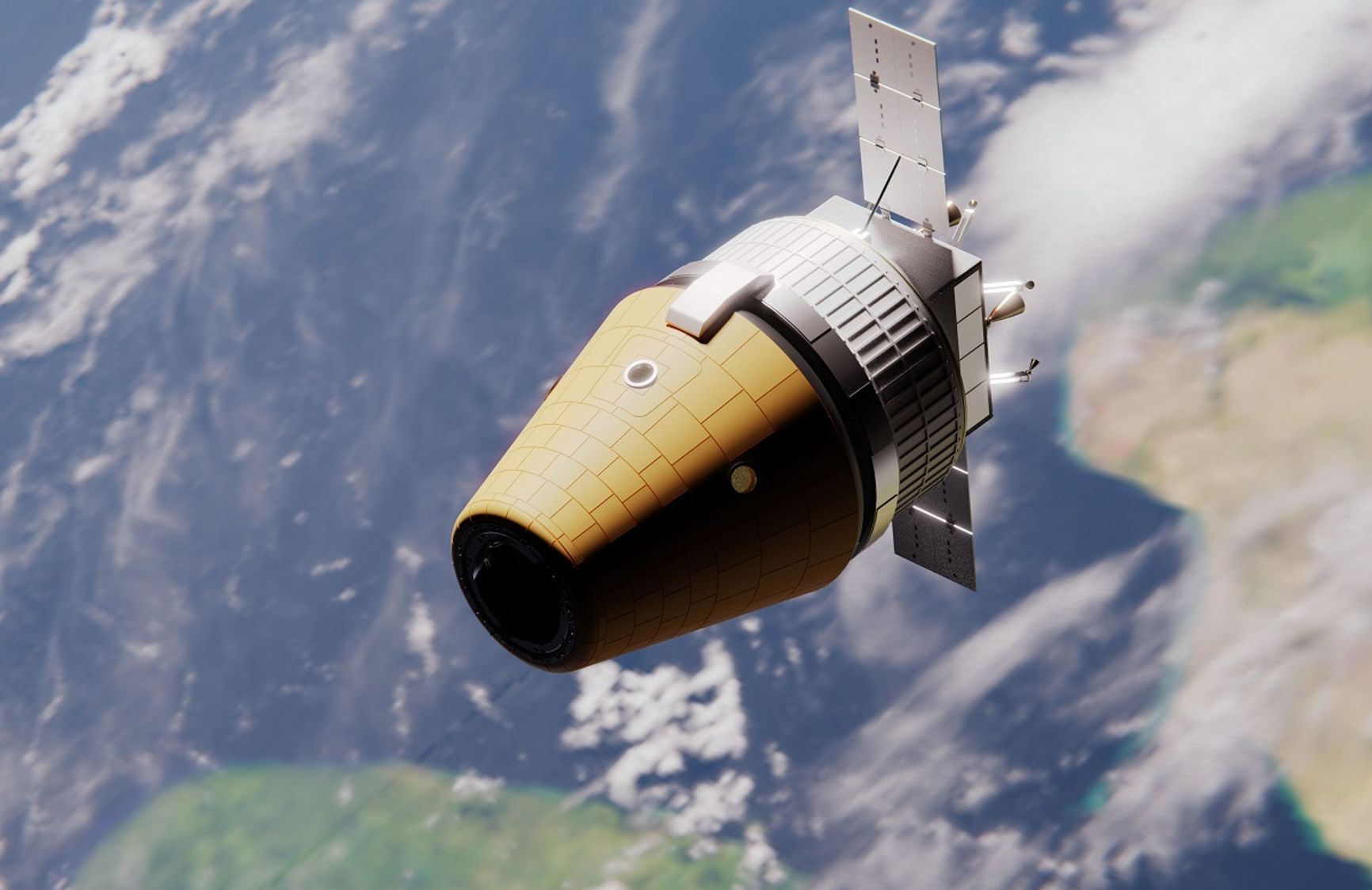

Since 2009, Russia's space rocket company Energia has been building a new manned spacecraft «Eagle» (previously called «Federation»), but the work has been delayed, particularly due to uncertainty with the launch vehicle to be used and over the purpose for which it is being built. Under the Federal Space Program until 2025, three flights of the new spacecraft are planned using the Angara-A5P launch vehicle: an unmanned low orbit flight (2023), an unmanned flight to the ISS (2024) and a manned flight transporting astronauts to the ISS (2025). The dates of these test flights has been postponed several times. The subsequent use of the spacecraft, for example, and whether it or any of its variants will be used for lunar flights, depends on the amount of funding in 2025-2035, particularly for building a super-heavy rocket required for flights beyond low-earth orbit.

Russia’s major activity in astronautics, are flights by manned Soyuz spacecraft and deliveries of goods by Progress cargo spacecraft to the Russian segment of the International Space Station. The medium-sized launch vehicle Soyuz-2, a descendant of the Vostok rocket which launched the Vostok spacecraft with Yuri Gagarin on board in 1961, is used for orbital launches. The only difference is that from 2020 onwards all manned launches can only be performed from Launchpad 31 at the Baikonur cosmodrome. Launchpad 1, the so-called «Gagarin's Launch», requires major repairs and was mothballed at the end of 2019.

Since 2020, two Soyuz spacecraft have been flying missions as part of the Federal Space Program, and it is planned to launch one Soyuz every year under a commercial contract with the American company Space Adventures. Such a spacecraft with one professional cosmonaut-commander will deliver two space tourists to the ISS.

The United States

Between 2011 and May 2020, the Americans did not fly into space on their ships, but today their manned space program is the most intense and ambitious. NASA oversees ISS integration, and the US segment is much larger than the Russian one, in particular because of the two lab modules of its partners: the European Columbus and the Japanese Kibo.

After the retirement of the Shuttles, NASA held a competition among contractors for building cargo and manned space vehicles to supply the ISS. The cargo ships Cygnus and Dragon (Cargo Dragon since 2020) are currently being used to transport cargo, and the operation of the Dream Chaser winged cargo ship will commence in the near future.

Since May 2020, NASA has been flying astronauts on SpaceX's Crew Dragon ships. Boeing's second manned spacecraft Starliner is currently undergoing flight tests before flying astronauts to the station. The third manned spacecraft, Orion, built by Lockheed Martin, will be used for lunar flights using Boeing's super-heavy Space Launch System (SLS).

Donald Trump, as President, launched a new lunar program, Artemis, and if the Joe Biden administration does not cancel it, there should be at least three flights to the Moon. The first, an unmanned flight utilizing the already existing rocket and spacecraft, is supposed to take place either in the fall of this year or in 2022, and the next two manned missions will fly around the moon and land two astronauts on the surface of Earth's satellite. In parallel with the Artemis program, NASA is working with Europe, Japan and Canada to design the Gateway, a station in lunar orbit with living quarters. The station's first two modules will be sent to the moon in 2023 using SpaceX's Falcon Heavy rocket.

Elon Musk's privately owned Space Exploration Technologies Corporation (SpaceX) stands out in the United States. Although its main goal in human space exploration is supplying the ISS, the company has its own plans. Rather than the ships themselves, NASA buys from SpaceX services for transporting crews to the ISS, so the company is free to use its ships at its discretion, namely, for commercial space flights. The first two contracts include an autonomous three-day flight on a Crew Dragon carrying four private astronauts this fall (the Inspiration4 mission) and a flight to the ISS carrying four private astronauts in early 2022 for Axiom Space.

But SpaceX's most important initiative is undoubtedly the Starship, a reusable super-heavy launch vehicle.

SpaceX-Starship-Mk1-17

The rocket will consist of two parts: the first reusable Super Heavy stage and the second reusable stage which is also the Starship spacecraft (the entire rocket assembly carries the same name), which will be able to launch 150 tons into orbit and return 50 tons of cargo to Earth. The total length of the assembly is 120 meters, the diameter is 9 meters.

Starship will fly using the Raptor oxygen/methane rocket engines. After the Starship's second stage is in orbit, the first stage will return to the launch pad and land softly on its six supports. To return to Earth, Starship will use aerodynamic braking in the atmosphere with its hull and movable aerodynamic rudders, and will land vertically on jet engines.

SpaceX is developing a super-heavy rocket at its own expense, but the company has already two contracts for its use. The Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa has paid in advance to fly around the moon in 2023-24 as part of the DearMoon project (dearmoon.earth). He bought out the entire flight, but he will be joined by a crew of approximately twelve people. SpaceX has also secured an initial-stage contract for utilizing the Starship launch vehicle to transport cargo to the lunar surface for NASA. The company has two competitors: Blue Origin and Dynetics. By the next stage, only one or two companies will be left.

China

The first Chinese cosmonaut, Yang Liwei, launched into space in 2003 on the Shengzhou-5 manned spacecraft. Since then, the Chinese human space program has grown consistently, following in the steps of the USSR and US space programs.

After several autonomous low-orbit flights of Chinese astronauts, two small stations with living quarters, Tiangun-1 and Tiangun-2, were put into operation, where astronauts can spend a maximum of one month. Having developed the Changzheng-5 (Long March 5) heavy rocket, China has commenced construction of a multi-module orbital station, whose base module is to be launched into space in April.

In 2021, development began on the Changzheng-9 super-heavy rocket, which is supposed to fly space crews to the moon by the end of the decade.

Changzheng-2 Launch

India

The Indian Space Research Organization is creating its own crewed spacecraft, the Gaganyaan, which is slated for its maiden flight with humans in 2022. The first astronaut squad has already been assembled, but the names are kept secret; it is known they have completed a course of general space training at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Star City.

Gaganyaan

What's next?

By the beginning of the 21st century, astronautics had become a very conservative field. Its purpose can be divided into several components:

1. Pragmatic space:

- Earth remote sensing satellites - used to photograph or produce radiolocation images of the planet's surface for military or everyday use purposes.

- Telecommunication satellites - provide communication, television and the Internet in areas which are hard to access by other means.

- Meteorological satellites - weather forecasts are needed by the military, scientists, and ordinary citizens).

- Navigation satellites - GPS, GLONASS, BeiDou.

Countries or large corporations are gradually developing their satellite constellations or launch vehicles (rockets) to solve defense tasks or to develop their businesses and gain profits. Space budgets have been growing, not in an abrupt manner but gradually.

2. Scientific space:

- Orbiters for remote study of planets (including the Earth).

- Orbiting telescopes that study the Universe in different frequency ranges (they are especially important for those types of radiation which cannot penetrate the Earth's atmosphere).

- Automatic landers and rovers that study the surface of planets, satellites and asteroids.

- Manned ships, space stations and biosatellites that study the effects of space flight conditions on living organisms. At the same time, humans can service space objects, for example, retrofit orbiting telescopes or install new sophisticated scientific equipment outside the space station.

- Unmanned space research programs expand the horizons of our knowledge about the Universe and the Solar System, but they have practically no influence on the development of modern astronautics. Plans for space research vehicles are made for the long term. For example, it took decades to partially implement the Russian Spektr space telescope program. The US James Webb telescope has been in development since 1997. Its budget has grown from $500 million to nearly $10 billion, with the launch scheduled for fall 2021.

3. «Space of Dreams»

Something that does not bring immediate commercial benefits or distinct scientific data, but for some reason inspires people.

Sleeping Through a Revolution

When a new country gets involved in space activities, it merely increases the overall funding for astronautics and achieves pragmatic goals like carrying out optical reconnaissance or telecommunications services; or gains a kind of prestige by putting into orbit a tiny nanosatellite often made of foreign components and launched on a foreign rocket.

Breakthroughs are possible only with a lot of flight experience and only if there are highly qualified specialists, the necessary scientific and technical base and sufficient funding not just for the development of a product but also for its subsequent marketing. The success of «garage startups» in information technologies is yet to be recreated in the area of space research. Yet, a revolution has taken place and, as is often the case, we have slept through it.

There has been a lot of talk about rocket and space vehicle reusability, and there have been many attempts to make partially reusable systems for launching payloads into orbit. Technically, orbital spaceplanes were the most successful: The Space Shuttle and Energia-Buran. The latter was curtailed for economic reasons. And the Shuttles, which had been put into operation exactly 40 years ago, turned out to be too expensive to maintain and insufficiently reliable (135 successful space missions vs two disasters, in which two Shuttles were destroyed and 14 astronauts killed).

When SpaceX founder Elon Musk publicly announced plans to make partially reusable rockets, the professional community was skeptical. Then, in 2016, the first stages of Falcon-9 launch vehicles proceeded to smoothly land on the launch pad and then onto sea barges, many experts questioned the cost-effectiveness of reusing the rocket's first stage. When SpaceX, with the help of the partially reusable Falcon-9, drove out the Russian Proton-M, the European Ariane-5 and the American Atlas-5 from the commercial launch market, it became clear that the rocket-building industry and the orbital launch market would never be the same.

Elon Musk's success was in part due to the weakness of his competitors. Europe took a long time to secure approval for the new Ariane-6 launcher project from the participating countries to please the contractors and it turned out that during the design process the rocket had become outdated even before its first flight. SpaceX's main competitor ULA, while creating its new disposable Vulcan rocket, abandoned its plans for the civilian market, focusing on military contracts where the launch cost is not a decisive factor.

Roscosmos has long been a critic of SpaceX and in 2018 it commenced building its two-stage Soyuz-5 launch vehicle, basically copying the Soviet Zenit rocket whose production had remained in Ukraine after the collapse of the USSR. But in 2020 it also began sketching a new partially reusable Amur-LNG rocket, which appeared similar to the Falcon 9.

Amur-NLG Rocket Project

A similar situation has developed with low-orbit satellite constellations for high-speed broadband Internet access. Many companies planned to do business in that area, but it was SpaceX who first began to deploy the Starlink satellite constellation using its own rockets. It has been manufacturing spacecraft at a faster rate than any other company. Currently, it has 1,378 satellites in orbit, the largest constellation of satellites of the same type in the history of mankind with 12,000 satellites planned for the initial stage.

If we try to find the reasons for SpaceX's success, we should look no further than the favorable business environment in the United States and the opportunity to experiment and to make changes in decisions, a luxury that is not available to large bureaucratic corporations, be it ULA, Roscosmos or Arianespace.

And in the popular eye, SpaceX is not merely a business entity that puts spacecraft into orbit or plans to provide Internet access, but a company that, in addition to pragmatic space, takes a swing at the «Space of Dreams» – mankind's expansion into outer space. It so happened that by the sixtieth anniversary of Yuri Gagarin's flight a private company, SpaceX, took over from government agencies and corporations in promising people the dream that had been inspired by the first cosmonaut.

Russia again. What about a super-heavy rocket?

OKB-1, which later became NPO Energia, has been planning interplanetary manned flights for decades. It developed the N1 super-heavy rocket in the 1960s and the Energia launch vehicle in the 1980s. By the 1990s the drawings were simply gathering dust in the archive, gradually becoming obsolete.

In 2014-15, when the draft Federal Space Program for 2016-2025 was being prepared, Energia proposed to include in it a super-heavy launch vehicle for a manned lunar program. But the Roscosmos technical council recommended not including a super-heavy launch vehicle for lunar missions and to focus instead on the Angara-A5V project for a heavy launch vehicle with an oxygen/hydrogen upper stage.

The main reason for the rejection of a super-heavy launch vehicle, in addition to its high cost, was the lack of additional payloads (other than the lunar ships themselves). Without such a rocket, if the lunar mission implementation proceeded according to plan with the Angara launchers it would have still been possible to launch and assemble in orbit a manned complex for flying around the Moon. It would have taken several launches utilizing heavy rockets.

However, since the possibility of assembling an interplanetary complex with a lunar landing module was later considered, the flight without a super-heavy launcher was conditional on the need to perform docking in orbit. And it required not just two separate launches, but also the presence of two Angara launchpads on the Vostochny cosmodrome – so that the interplanetary complex modules could be launched in the same orbital plane within a short time interval. Thus, according to the lunar program in addition to the Angara launcher itself two launchpads were planned - the strategy was confirmed on March 31, 2017 by the expert council of the Military-Industrial Commission board chaired by Dmitry Rogozin.

In 2019 Russian scientists sent Dmitry Rogozin’s eerie effigy into the atmosphere behind the wheel of a bright red Zhiguli toy car

But on May 22, 2017 in Sochi an unexpected turn occurred in the development strategy of Russia's lunar program. Vladimir Putin decided to abandon the manned version of the Angara launcher and to build instead a different rocket, the oxygen/kerosene Soyuz-5, and move the launches to the Baikonur cosmodrome (the first Federation spacecraft launch was planned for 2022). It was also decided to cancel the construction of a second Angara launch pad on the Vostochny cosmodrome replacing it with launching facilities for a super-heavy rocket (later called Yenisei) to be built by Energia and Progress based on the Soyuz-5 rocket modules. The new rocket was needed for the implementation of Russia's lunar program which requires a rocket capable of lifting upwards of 100 tons of cargo into low orbit.

After that, the following events occurred:

1. On July 17, 2018, after Dmitry Rogozin took over as head of Roscosmos, a government contract was signed with Energia for the creation of a medium-class space rocket complex with a Soyuz-5 launcher.

2. During Putin's September 6, 2019 visit to the Vostochny cosmodrome, Rogozin reported that the launch of the Federation spacecraft was postponed from 2022 at the Baikonur cosmodrome to 2023 at the Vostochny cosmodrome. Now, instead of the Soyuz-5 launcher (also known as Irtysh), the Angara-A5P launcher will again be used.

3. In August 2020, Vladimir Solntsev, former General Director of Energia who proposed the design of the Soyuz-5 launcher and the super-heavy Yenisei, was arrested for embezzling 1 billion rubles.

4. On December 15, 2020, Rogozin wrote on Facebook that a super-heavy launch vehicle should be created based on fundamentally new technical solutions. On the same day, however, Roscosmos signed a 1.47-billion-ruble contract with the Progress Rocket and Space Center for designing a super-heavy-class space rocket complex Yenisei based on the Soyuz-5 oxygen/kerosene rocket.

5. On December 16, 2020, a meeting at the Space Council of the Russian Academy of Sciences recommended that Russia should postpone the development of the super-heavy rocket for its lunar program due to the absence of payloads and high development costs (estimated by Roscosmos at 1 trillion rubles), and should focus instead on the Angara-A5V heavy rocket project with a multi-launch lunar flight scheme. But due to the lack of a second Angara launch pad at the Vostochny cosmodrome, specialists will have to develop a complex scheme for lunar flights. Due to rocket capacity limitations, instead of the four-seater ship Eagle (previously known as Federation) for lunar flights, it is planned to build a lighter two-seater Orlyonok spacecraft.

6. In February 2021, head of Progress Dmitry Baranov said the work on the Yenisei super-heavy launch vehicle being designed as part of the Russian lunar program had been suspended. Now, instead of the launchpad for the Soyuz-5 rocket and the Yenisei super-heavy rocket at the Vostochny cosmodrome, the third stage of launching facilities construction is planned for the Amur-LNG two-stage reusable oxygen/methane launcher (also designed by Progress) which looks similar to SpaceX's Falcon 9 launch vehicle. It is planned that liquefied natural gas (LNG) will be used for fuel.

7. By March 2021, Roscosmos companies determined a new concept for Russia's Amur super-heavy launch vehicle to be used for lunar flights after 2030 - it will utilize oxygen/methane engines, which have never been used on Russian rockets before.

All this may seem rather confusing, but the bottom line is simple. There are two main rocket design schools in Russia: the Khrunichev Space Center which manufactures the Proton and Angara launchers, and Energia/Progress which proposed the Soyuz-5 launcher and the Soyuz-5 based Yenisei super-heavy rocket. In 2017, Putin opted for the Yenisei project.

According to estimates, however, such a complex and ambitious project might have cost at least 1 trillion rubles per decade. And had such an expensive rocket been created, Russia wouldn't have had adequate payloads for it, except for a few flights to the moon. The government did not approve the program, and on November 2, 2020, Putin voice his criticism of Roscosmos. Without funding for the Yenisei project, Roscosmos was forced to announce the postponement of the program. But in order not to create the impression that the rocket, which Rogozin had talked about for four years, had been abandoned, it was announced that the super-heavy launcher would be created after all, but at some point, in the future using brand-new reusable technologies. It would boast methane engines and a new name, Amur. So, we circle back to the heavy Angara launcher for the lunar program. Minus the lost time and one of the two launch pads at the Vostochny cosmodrome.

The reason for all of this is the lack of a clear space strategy in Russia and the attempts to grab the largest slice of the pie within the industry. Coupled with the bureaucratic delays which are customary to the government sector, cancellation of contracts immediately after their signing looked especially surreal. In such a situation, no one can say whether Russia will be able to send its cosmonauts to the Moon even as late as the 2030s, given that Roscosmos refused to participate in the construction of the international Gateway lunar station.

Main Picture - Ivan Belyaev, Vologda