On Sept. 13, the Central Bank of Russia raised its key interest rate to 19% and warned of further hikes to come. The Central Bank claims the move was necessary to combat inflation, which it attributes to an alleged excessive rise in domestic demand. However, there is an alternative viewpoint. According to economist Valery Kizilov, it was the Central Bank itself that fueled inflation by unjustifiably expanding the monetary base for years while simultaneously encouraging a credit boom. Russia has grown accustomed to living with an inflation rate of close to 10%, negligible real growth, and interest rates on loans exceeding 25% per year. Breaking away from this course is difficult, writes Kizilov, and those caught up in the euphoria tend to ignore the risks and disregard the future.

The long-awaited credit shock

Mortgage lending in Russia has sharply declined, with the total housing loans issued in August being down 56% from the same month in 2023. Non-subsidized market programs, which accounted for 1 trillion ($10.6 billion) of the total 3.6 trillion rubles ($38.16 billion) issued from January to August, saw a 51% drop compared to a year ago. This trend is expected to continue, as average mortgage rates have hit a record high of 20.8% per year. It's not just that the government has ended its large-scale subsidy program — the increase in the key interest rate to 19% is making credit more expensive across Russia as a whole.

Cash loans are currently being offered at a 27.1% annual interest rate — the highest since April 2022. Even the state, when issuing one-year OFZ bonds (coupon-bearing federal loan bonds issued by the Russian government), is borrowing at 17.25% per annum, compared to a rate of 13.32% for similar bonds in January.

Cash loans are currently being offered at a 27.1% annual interest rate — the highest since April 2022.

The cost of credit includes both inflationary and real components. The Bank of Russia estimates that the annual rise for consumer prices in 2023 was 7.4%, while that from Aug.1, 2023 to Aug. 1, 2024 was 9.1%. While the inflation rate has clearly accelerated, it hasn’t increased as much as the yield on OFZs. If you subtract the inflation rate over the last 12 months from the nominal yield of one-year OFZs, you'll find that in Jan. 2024, the real yield was 5.92%, rising to 8.15% per annum by August.

The increase in the key interest rate set by the Bank of Russia is far from the main factor driving up the cost of credit. After all, the Central Bank's loans make up only about 3% of Russian banks' liabilities, which is 8–9 times less than funds from private individuals and 10–11 times less than funds from other Russian banks. Commercial banks could entirely avoid borrowing from the Central Bank, and their total debt to the Bank of Russia was no more than 5 trillion rubles ($53 billion) as of June 30, while they had about 14 trillion rubles ($148.4 billion) in their accounts at the Bank of Russia.

Why are real interest rates rising in Russia? From an economist's perspective, the reason might either be an increase in demand for credit or a decrease in supply.

An increase in credit demand means more borrowers are willing to borrow larger amounts at higher rates. Who are these borrowers? Some take loans for profitable investments, while others borrow to finance current spending beyond their incomes. The first group takes out investment loans, and the second group takes consumer loans.

Demand for «investment» loans increases when more lucrative investment opportunities arise. This typically happens when new technologies and business models are discovered but haven't yet been implemented, when untapped natural resources are identified, or when new trade routes become available but are not fully utilized. This type of borrowing requires business optimism — a sentiment that’s currently scarce in Russia.

In contrast, demand for consumer credit rises when people prioritize the present over the future, disregarding the reality that they'll eventually have to tighten their belts to pay back high-interest loans. This can occur among those facing immediate financial hardship, those consciously choosing present pleasures over future security, or those who expect an uncertain and risky future — one that makes saving seem futile.

Sociologists and psychologists could investigate how prevalent these motivations are among Russians, especially since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Intuitively, it seems these attitudes are becoming increasingly common, as if the country has given up on itself and is squandering its future.

It seems as if Russia has given up on itself and is squandering its future.

Alternatively, the issue may not be an increase in credit demand but rather a decrease in supply. This, too, could be due to shifting preferences from the future to the present. Previously, someone might have saved a tenth of their monthly salary, but now they've stopped.

Similar reasoning applies to entrepreneurs and investors. Lending becomes riskier in times of prolonged dictatorship and war, which heighten the threat of loan defaults, currency devaluation, oppressive regulation, taxation — and, finally, crime. These are known as “country risks.” At present, they are particularly high in Russia, and they are continuing to rise. No one will lend at low-interest rates in such an environment.

No one will lend at low-interest rates in a high-risk environment.

The stock market decline observed in Russia in recent months is also linked to the rise in interest rates. Let's take a step back and review Russian stock price dynamics over the past few years. The Moscow Exchange Index reached a record high of over 4,200 in October 2021 — shortly before Vladimir Putin issued an ultimatum to NATO. In the first days of the invasion in Feb. 2022, the index plummeted, and by Mar. 1, 2022, it had fallen below 2,500 points. It then gradually recovered, hitting the 3,500 mark by May 2024.

On Jul. 26 of this year, when the Bank of Russia raised the key interest rate, the Moscow Exchange Index stood at around 3,000 points. By early Sept. 2024, it had dropped to around 2,500–2,600, matching the lows seen right after the start of the invasion in March and April 2022. The logic here is simple: more expensive credit means higher yields and lower bond prices. As a result, investors shift funds from stocks to bonds, and stock prices fall. This stems from a sense that there are many risks, few prospects, and a future that simply is not worth investing in. The source of this sentiment isn't the Bank of Russia, but the country’s higher authorities.

How the Bank of Russia explains high inflation

So are people wrong to blame Bank of Russia head Elvira Nabiullina for the high interest rates? Was raising the key rate necessary to combat inflation? And do all developed countries turn to these measures under similar conditions?

A free market interest rate in today's Russia cannot be too low. If the central bank started offering loans at artificially low rates, it would flood the economy with printed money, truly accelerating inflation (and nominal interest rates would rise accordingly). However, it's worth considering why inflation was already quite high in the first place.

An excerpt from the central bank’s minutes of July 26, when the key rate was raised from 16% to 18%, makes for disheartening reading:

“The acceleration of current price growth rates in recent months was partly due to temporary factors: in April — the indexation of telecommunications tariffs; in May — a one-time increase in prices for domestic vehicles; in June — a shift in the seasonality of fruit and vegetable production. Additionally, in May-June, rising tourism service prices, which have been highly volatile in recent years, made a significant contribution to inflation. But even if we exclude these factors, core inflationary pressure in the second quarter was higher than in the first. Moreover, most participants agreed that the high growth in tourism service prices in recent months reflects increased consumer demand and should not be excluded when assessing core inflationary pressure.”

In short, according to the Central Bank, it seems that anyone but the Central Bank is to blame: travel agencies, car and vegetable sellers, telecom companies, and as the root of all evil — “increased consumer demand.” This has been ongoing for five years, as 2019 was the last time when Russia’s average annual inflation did not exceed the 4% target.

For example, here's the Central Bank’s explanation for the excessive inflation in 2023. Once again, we are to believe that demand was to blame:

“The economy reached pre-crisis levels, and physical limitations on further growth became increasingly evident, primarily a labor shortage. The accumulated pace of internal demand growth began to outpace the capacity to expand supply. Inflationary pressure began to rise. This was a sign of an overheating economy — when demand increasingly goes not into the production of additional goods or services, but into accelerated price growth.»

In 2022, sanctions were naturally blamed, but “panic”-driven demand didn't go unnoticed that time either:

“The initial shock from sanctions resulted in extremely high volatility of the ruble, and along with external import restrictions, triggered panic buying of certain goods and cash. There was a significant risk of accelerated inflation and threats to financial stability. Thanks to the experience gained in inflation targeting, it was possible to quickly prevent a price surge, minimize risks to financial stability, and return loan and deposit rates to pre-crisis levels within a few months.”

It turns out that improper demand creates inflationary pressure both in crises and when emerging from them. If so, in 2021, there must have been “overheating” as Russia emerged from the crisis, and in 2020 — “volatility” and “panic.” Let's see if this is indeed the case. The Central Bank writes:

“By mid-2021, the Russian economy, except for a few sectors, returned to its pre-COVID growth trend. At the same time, inflationary pressure increased significantly — as a result of the stimulating economic policy of 2020 and pandemic-related production restrictions in the Russian and global economies.

The Bank of Russia, viewing pro-inflationary factors as largely persistent, began raising the key rate in March 2021. Over the year, it went up by 4.25 percentage points to 8.5%. However, additional pro-inflationary factors in the last months of the year (a poor harvest, the ruble weakening due to rising geopolitical risks, and high inflation expectations) hindered the slowdown of current price growth. By the end of the year, inflation reached 8.4% — double the Bank of Russia's target. In most large developed and emerging economies, inflation accelerated throughout the year, significantly exceeding target levels in some countries: about threefold in the U.S., UK, and several others.”

In other words, instead of “overheating,” the Russian economy of 2021 simply saw a return to the pre-COVID trend — with its inherent pro-inflationary factors. To be fair, the Central Bank did mention that inflationary pressure resulted from the “stimulating economic policy of 2020.” It's just unfortunate they didn't clarify who implemented this policy or whether it included an increase in the money supply. Also unaddressed was the question about whether this inflationary pressure came as an unpleasant surprise to the policy's authors, or if it was intentional.

The 2021 results mention familiar themes: criticisms of fruit and vegetable products, ruble depreciation, and the public’s inflationary expectations (allegedly the cause of, rather than the consequence of inflation). The bank wanted to comfort us with the fact that inflation in the U.S. and UK exceeded targets threefold, while in Russia, it was only twofold. However, such comparisons weren't made in the Bank of Russia's annual reports in other years, and they failed to mention the fact that inflation targets in other countries are often lower than in Russia — over the period in question, prices in the UK rose by 2.6% and in the US by 4.7%.

Even further back, the Central Bank pointed to “cost-push inflation” as a factor. Coming from a professional like Elvira Nabiullina, this can't be taken as a sincere explanation. If, under conditions of a stable money supply, real costs rise in some sectors, there will be a shift in relative prices without changing the overall index level. For instance, if fuel and heating become more expensive, consumers cut back on luxury items, causing their prices and production factors to drop. If the average price level rises — which we consistently observe — one must first examine changes in the money supply, most likely increased by the Central Bank itself.

Why inflation in Russia is actually high

The amount of cash in the economy and commercial banks' balance sheets is a figure entirely controlled by the Central Bank. If the goal is to keep inflation at no more than 4% per year, then logically, the monetary base should also increase by no more than 4% annually.

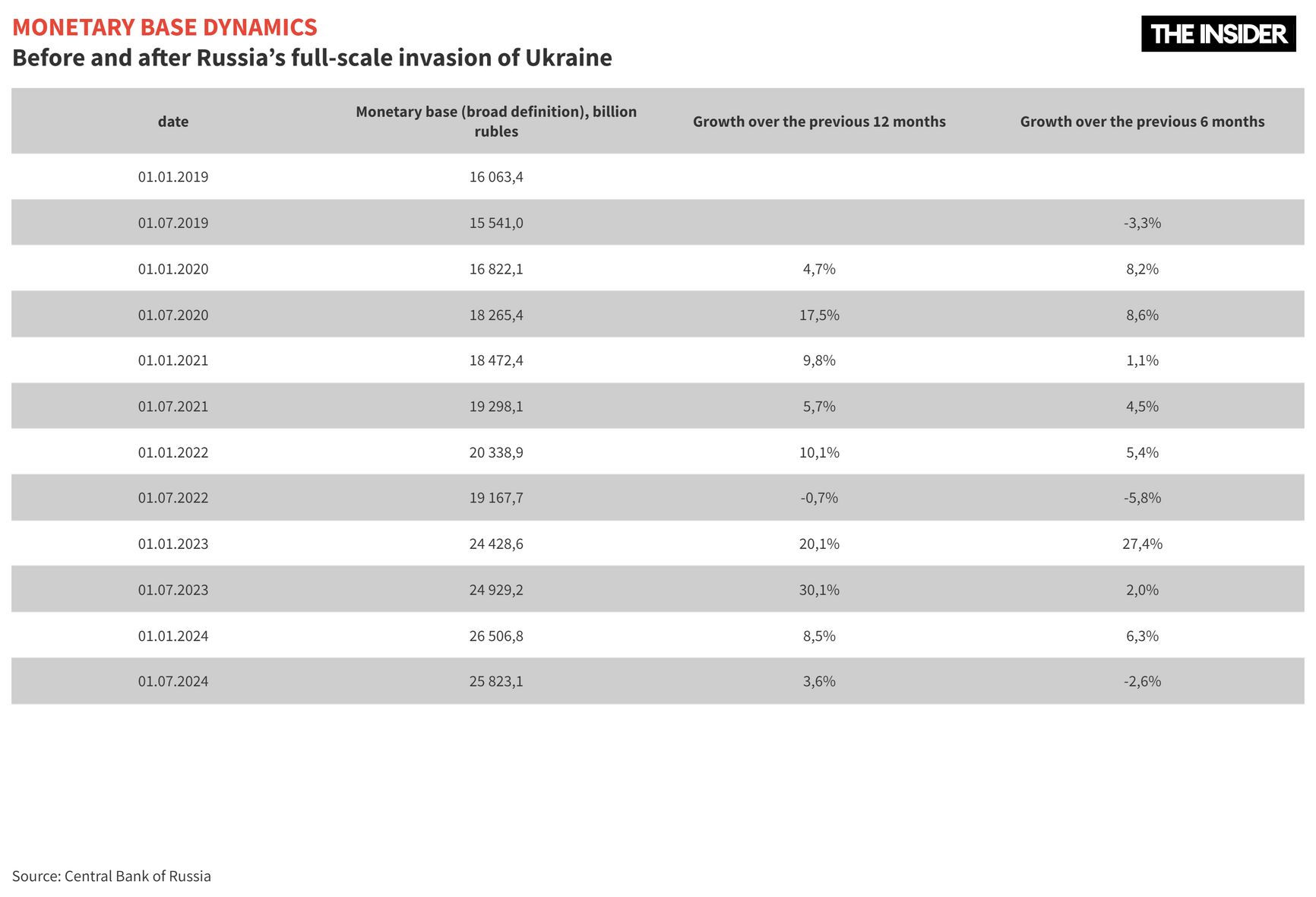

However, Nabiullina's agency expanded the monetary base by 4.7% in 2019, 9.8% in 2020, 10.1% in 2021, 20.1% in 2022, and 8.5% in 2023.

Looking at half-year intervals reveals even more abrupt changes: in the first half of 2022, the monetary base was cut by 6%, then increased by 27% in the second half of the year. In the first half of 2023, it grew by only 2% in the first half, then by over 6% in the second half. In 2024, it began to freeze again.

These fluctuations are sometimes attributed to the idea that the Central Bank needs to stabilize not just the supply of cash, but the broader money supply — which includes all bank deposits, both of individuals and of businesses. Deposit levels aren't directly controlled by monetary authorities and can change with market conditions. If the economy takes a downturn, deposits might fall sharply, requiring central bankers to balance them with a “countercyclical” increase in the monetary base. Let's examine whether the Bank of Russia's actions follow this principle.

Over the past five years, the amount of money (the so-called “money supply”) in Russia has been growing. What does this mean? Back in 2019, Russia’s monetary base increased by 5%, while the supply grew by 10% — pure monetary expansion. Russia’s money supply was growing even without the intervention of the Central Bank, so why it needed to increase the base is unclear.

Russia’s money supply was growing even without the intervention of the Central Bank, so why it needed to increase the base is unclear.

Both indicators continued to increase each year. However, it is clear that the Bank of Russia's issuance was not compensating for a drop in deposits, as deposits were actually rising, with commercial banks creating money at a faster rate than the Central Bank. It was only in the first half of 2024 that the Bank of Russia reduced the money supply — but commercial banks more than made up for it, leading to an overall expansion.

Why does Elvira Nabiullina need the emission?

The Bank of Russia may not be to blame for expensive credit, but it is still responsible for inflation: it printed too much money, and it remains unclear why this was done. The term “disinflationary risks” sounds strange. If inflation is harmful, why is getting rid of it considered risky?

Educated Russians have a straightforward and logical view of how inflation arises. If the government spends more than it receives, it covers the budget deficit with money issuance. The amount of money in the economy increases. Now more money chases the same volume of goods and services, and everything naturally becomes more expensive. This logic was taught to us in the 1990s, and all reasonably liberal economists spoke about it back then.

However, for the past 25 years, Russia hasn't operated this way. Under Putin, there were initially no budget deficits, and even after they later emerged, they remained moderate — comparable to levels in developed countries in which inflation is usually below 5% per year. Even during the war, Russia's budget deficit as a percentage of GDP is smaller than that of the U.S., Japan, the UK, France, or Italy. And yet Russia’s inflation is higher — and so is its level of monetary emission.

Even during the war, Russia's budget deficit as a percentage of GDP is smaller than that of the U.S., Japan, the UK, France, or Italy.

Why increase the money supply so much if the budget doesn't need it? People like me will never understand this. The Central Bank, however, has an explanation — it believes issuance is needed not as a budget filler, but as a stimulus for the entire national economy. It claims that credit is beneficial, and moderate issuance encourages credit. Issuance is considered moderate so long as it doesn't scare people away from the national currency.

In places like Zimbabwe or Venezuela, issuance is excessive. When people get their hands on their national currency, they know they have to spend or exchange it for foreign money as soon as possible. The situation in Russia in the 1990s was similar. But in the 2000s, it was a different story. If ruble savings tended to depreciate threefold in a year, people would opt to save in U.S. dollars — but if they depreciate by just 7%, 12%, or 25%, one might shrug and keep them in rubles, hoping not to lose more when buying foreign currency. The central bankers’ wisdom is built on understanding this psychological mechanism.

When the consumer is trusting and calm, the money supply can grow faster than inflation, real economic growth, or even nominal GDP growth. This allows reports of rapid growth in banking services — deposits, loans, cards, payment systems. The central bank appears competent, progressive, and prestigious. The assets and volumes of the banking system grow, and their complexity increases. This means more objects for regulation and control, larger budgets, more staff, and greater authority for the Bank of Russia's leadership. People get used to previously unfamiliar financial services, start believing in their reliability, and as a result open up to the idea of increased state guarantees, inspections, and mechanisms of control. At the same time, a selection process unfolds among commercial bankers: only those who recognize the necessity of cooperating with the regulator manage to survive. After all, who would refuse such a setup?

When the consumer is trusting and calm, the money supply can grow faster than inflation, real economic growth, or even nominal GDP growth.

This motive is common for central bankers in both developed and underdeveloped nations, large and small, pro-American and anti-American. However, if a country is peripheral, isolated, and poor, this motive is even stronger. In the developed world, people are less tolerant of inflation. They might forgive a 10% devaluation under extreme circumstances, but never 25%. In places where people are more accustomed to real hardships, they'll endure 25% a year.

One way or another, central bankers always monitor market participants' sentiments and try to manage them both directly and indirectly. Hence, their favorite tool is «verbal intervention.» The results of this management are reflected in the multiplier.

How commercial banks and borrowers contribute to inflation

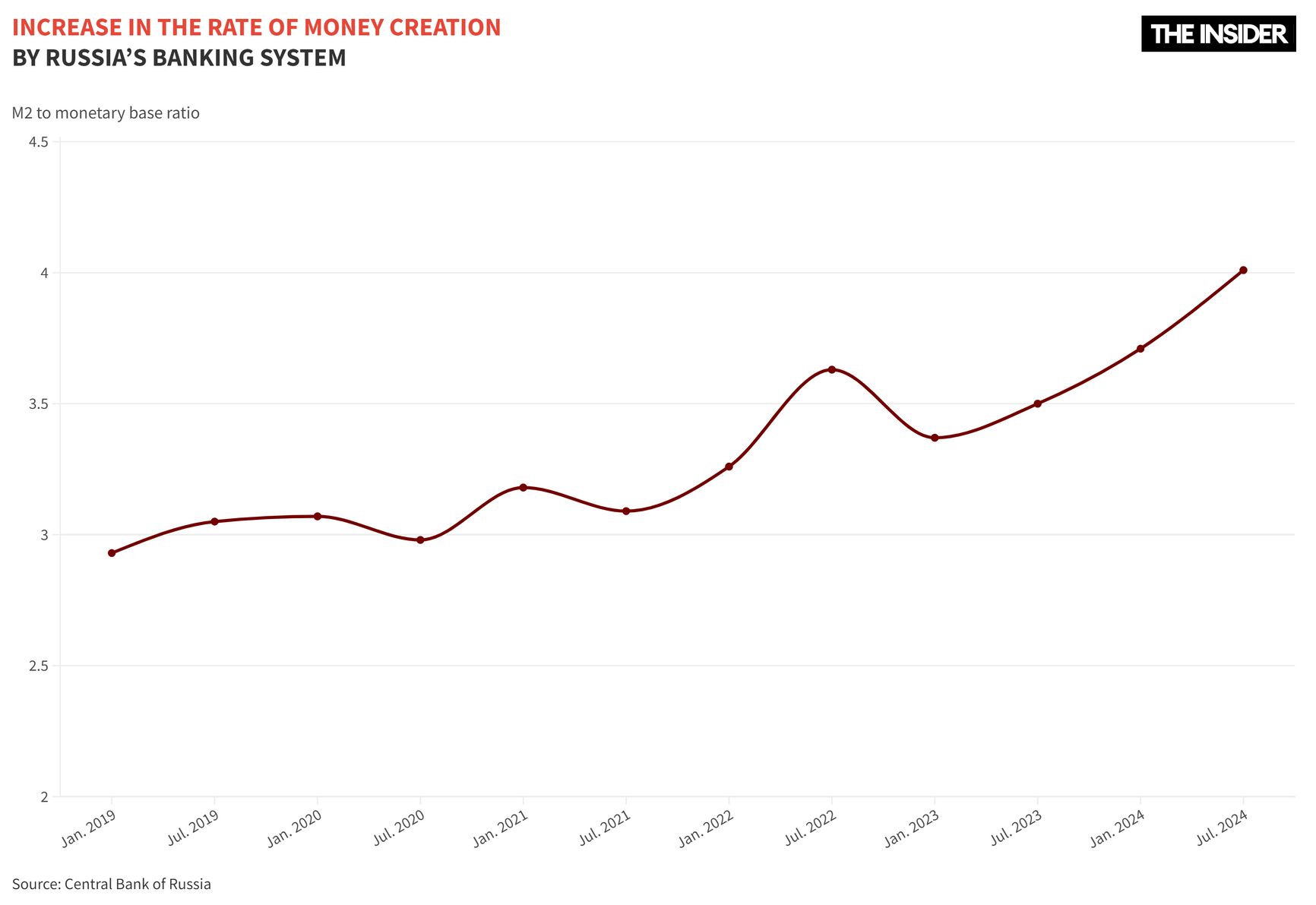

The ratio of the money supply to the monetary base reflects how actively the banking system creates money. During times of crisis, this ratio should decline, while in periods of economic boom it should rise. This indicator is influenced by policy but isn't directly controlled by the authorities. Overall, the multiplier illustrates the extent of the credit bubble in the economy.

In recent years, we've seen this ratio rapidly increase in Russia.

The situation can be described as one of euphoria and frenzy. Depositors, ignoring risks and low rates, are pouring money into banks. Banks, fearlessly, issue more and more loans. Borrowers, undeterred by the high cost of these loans or the fact that they're already heavily in debt, borrow ever more. They promptly spend the borrowed money on goods and services. Sellers of goods and services deposit the money in banks. Banks issue even more loans. The cycle repeats — and credit levels snowball. The logical end to this euphoria is always panic and collapse.

Depositors are the ignoring risks and pouring money into Russian banks.

Long-term trends indicate that bank loans in Russia are currently at unprecedentedly inflated levels. Economic crises in Russia are typically drowned in money issuance, resulting in weak economic cycles and — almost always — high inflation.

What’s next?

The monetary tightening announced by the Bank of Russia in July is unlikely to last long. It is hard to imagine the authorities decisively and consistently stifling the credit euphoria they've fueled for years, as it has already taken deep psychological root among the population. It's hard to go against expectations, and the expectations are quite clear. Russians are used to prices rising about 10% a year, with the money supply growing slightly faster. There will be more loans, and interest rates will hover around 25–30% per year. The real GDP will grow at a rate of approximately 0% annually, but official reports will show a growth of around 3%.

This stagnation won’t provoke mass protests or fears for the future. The brief panic at the start of the war was quickly suppressed, and it's hard to say what played a bigger role: the hypnotic talents of Elvira Nabiullina, who can be placed alongside the “maestro,” former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, in the art of market manipulation, or the specific nature of an audience so receptive to calming rhetoric.

Investment prospects in Russia are viewed pessimistically, but the view on consumption is quite optimistic. Quite simply, many want to join in on the credit feast during the plague. Most in Russia are ready to grumble and express their dissatisfaction with the authorities — in reality, however, most only choose to believe in the things that calm and soothe them.