Vladimir Zhirinovsky, who predicted the war with Ukraine within two days, never found out it had started, and never saw the result of his many years of work. The politician's funeral was organized at the highest level: Vladimir Putin came to say goodbye in person. Writer and historian Sergei Medvedev analyzes how Zhirinovsky legitimized Russian fascism, fully adapted by Putin into state policy.

The patriarch of Russian politics, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, has died. Far from being the oldest - only 75, an age of maturity on the Russian Olympus; far from being the most titled, he was unequivocally (his favorite word, spoofed by the «Puppets» program) one of the pillars of the post-Soviet era. Moreover, it was he who, in a buffoonish and grotesque manner, formulated the political program of revanchism, which became the official doctrine of Russia in the 2020s, and was the godfather of Russian fascism, which rose to prominence with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine.

The funeral service for the deceased at Christ the Savior Cathedral and the attendance of President Putin (or his look-alike) at the service definitively canonized the deceased as the key politician of the last thirty years. He himself predicted such a funeral many years before his death, just as he predicted so many things in general, including, to within two days, the outbreak of war in Ukraine - and this prophetic gift speaks not so much to the deceased's vast knowledge as to the fact that he unmistakably felt the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the times, and shaped that spirit himself.

He started out as a spoiler for the democratic movement, presumably planted by the state security agencies under the guise of first a social-democratic and then a liberal-democratic party. As a leader-type politician, he predictably failed with democracy, and with his unique intuition he recognized the path that would lead him to triumph, and, ultimately, to the collapse of Russia: at the first Russian presidential election in 1991, he unexpectedly said that «the Russian question is the main thing»: «155 million Russians are in the most humiliated and insulted position! This is the most spat at nation!» And so, his star began to rise: in that election he came third with almost 8 percent of the vote, while in the 1993 parliamentary elections the LDPR had already won with 23 percent of the vote, which prompted the publicist and former deputy Yuri Karyakin to utter an epic cry: «Russia, come to your senses, you've gone nuts!»

«Russians are the most spat at nation!» Zhirinovsky declared in 1991

The same «nutty» Russia the mouthpieces of perestroika had not wanted to acknowledge, which today is shooting, torturing, raping and pillaging in Bucha, Gostomel and Mariupol, had for years become the electoral fiefdom of Zhirinovsky. The core of his electorate consisted of middle-aged older people and residents of urban suburbs, depressed regions, small towns, with low educational levels and social capital, with a military or criminal past: those who had more to lose from reforms, were resentful of the world of freedom and globalization, and nostalgic for the Soviet past. They were not a dominant force in Russia, either electorally or demographically, but they constituted that social heartland, the «garage guys» that Surkov would later call the «deep people» - and Zhirinovsky began speaking their language, pointing out their sore spots, giving them language and a voice, legitimizing their vague resentment against life and turning it into his political capital.

He steered clear both from the intelligentsia's version of Russian nationalism, with a prayer book in hand and cabbage in beard, and from the grim determination of skinheads and bloodied knuckles of neo-Nazis at the «Russian marches,» but he had a gift for saying things from the rostrum that at the time seemed taboo, obscene, marginal, and were supposed to be confined to kitchens, beer halls and garages.Thanks to him, they entered public discourse and political language and eventually became the discourse of power itself.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

Zhirinovsky legitimized the four main elements of domestic fascism, the main one being bitterness, on which such an intricate moral complex as resentment (a word that is now thrown around left and right) is based. Nietzsche called it «the morality of slaves,» the jealousy of the loser, the powerless hatred of the slave toward the master whom he considers the cause of his failures. Zhirinovsky started talking about resentment when it had not yet become a political fashion. Moreover, in the early 1990s, the political and economic elite was rather euphoric about the prospects that had opened up, about the plasticity of reality and the possibility of changing it overnight. There were lockdowns, bankruptcies, semi-hunger, street crime and ethnic conflicts on the periphery - but people were inclined to blame it on the Soviet past and the rotten system, and in the West they saw an example and a civilizational perspective. It is hard to believe this now, but at that time the active part of the population did not hold a grudge against the outside world, but rather a desire to join it.

Zhirinovsky was the first to speak publicly about the humiliation of Russia. I remember my surprise when I first saw a huge LDPR billboard in Moscow, «For the Russians, for the poor!» I thought at the time: why are Russians poor? Against the backdrop of Central Asia, Moldova, Belarus, and Ukraine, Russia seemed like an island of prosperity, attracting investment, building its garish capitalism, and attracting migrants, but Zhirinovsky skillfully constructed a narrative of losers. By the mid-1990s, the whole political elite started to talk about Russian resentment - and then came the laments about the «major geopolitical catastrophe» - the collapse of the USSR (Putin, 2005), and the lists of claims against the West (Putin's Munich speech of 2007).

Out of resentment was born the second element of Zhirinovsky's fascist eccentricity: imperialist revenge. «I will raise Russia from its knees!» read his campaign poster from 1993, anticipating one of Vladimir Putin's main slogans for the next fifteen years. The leitmotif of restoration of the USSR ran through his speeches: «Our wish to all the former Soviet republics: we have had our fun, enough is enough. It's time to go home.” A couple of decades later, these flamboyant statements returned with all their seriousness in Putin's programmatic statements about the «gifts from the Russian people» to the fraternal republics that needed to be returned.

The leitmotif of restoration of the USSR ran through Zhirinovsky's speeches

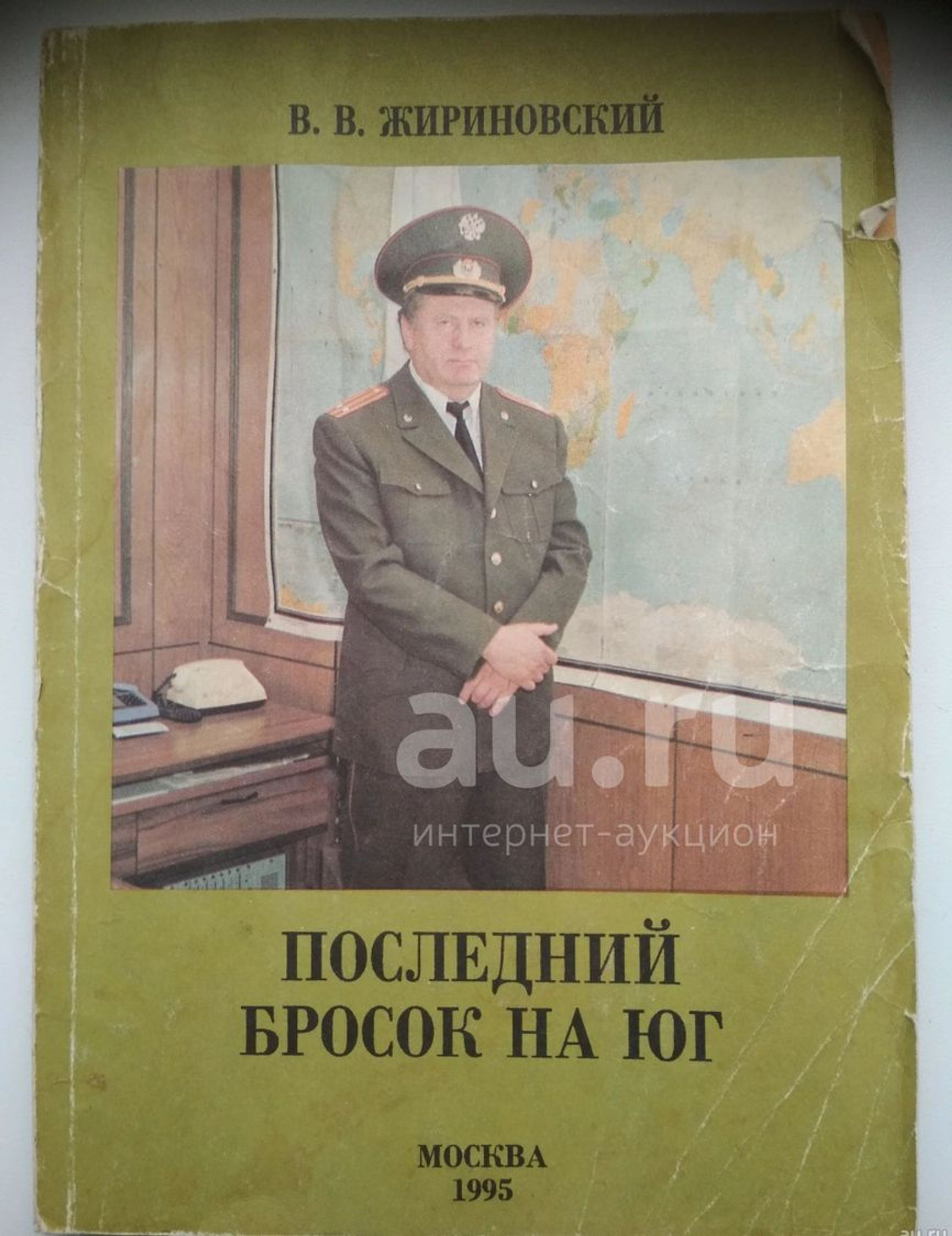

Expansionism is the third horseman of the Apocalypse according to Zhirinovsky. One of his most famous quotes, about a Russian soldier washing his boots in the Indian Ocean, is essentially apocryphal, a myth which our hero had lazily denied - but whether he said it or not, he dreamed of «The Last Rush to the South» (the title of his book), called for bombing Baghdad, Tbilisi, Istanbul, realizing the old imperialist dream of a shield on the gates of Constantinople. Here again, Putin followed in his footsteps in the southern vector of his foreign policy: the war in Syria, the confrontation with Turkey, the intervention of Russian forces in Libya and the Central African Republic.

Finally, the fourth element is xenophobia. Zhirinovsky hated everyone: from the Caucasus, which he promised to surround with a barbed wire fence, to Ukraine, which he didn't consider a real state when he called for taking Sevastopol back in the 1990s, from migrants to Jews, whom he accused of inciting anti-Semitism. Separately, he lambasted liberals, multiculturalism and Western tolerance, which was surprising to hear from an extrovert, comedian, half-breed and bisexual Jew with a penchant for red and canary jackets and an entourage of handsome young men: he could have been an ideal hate target for the «garage guys,» but instead he had formulated, for them, their rejection of everything new, flashy, and foreign.

All this sounded dissonant in the tolerant and pluralistic atmosphere of the 1990s but became mainstream in the rapidly advancing archaic Putin era - with its chauvinism, militarism, orthodoxy, «spiritual bonds» and homophobia. Cultivated hatred of the Other became the basis of domestic politics and the new social contract; during Putin's third term, after the defeat of the Bolotnaya Square protests in 2012, it became a key technology of power, suggesting the final shape of fascism in Russia. Over the past decade, the role of the Other has been filled, consecutively, by foreign adoptive parents, LGBT, feminists, liberals, the «fifth column,» falsifiers of history, «our Western partners,» America and the «Anglo-Saxons» (a word that suddenly emerged in the Russian propaganda vocabulary as if from Hitler's press), the harmless Czech Republic, which unexpectedly made the list of Russia's greatest enemies, and the proud Poland stuck like a bone in the throat of the handlers of «historical politics». And finally, exactly as Zhirinovsky predicted, Ukraine became Enemy Number One.

Exactly as Zhirinovsky predicted, Ukraine is Enemy Number One

Future historians will most probably reconstruct how and when Ukraine took hold of Vladimir Putin's paranoid imagination - whether it was during the first Maidan in 2004, when «color revolutions» broke out around the empire, or during the second one in 2013; whether it had been the unexamined childhood trauma or the grown-up jealousy of an abandoned loser husband, but the fact is that Ukrainians were to him what Jews had been to Hitler: a thorn in the picture of the universe. All of his pseudo-historical articles of the last year, all of his utterances, bubbling with contempt and vulgarity («put up with what I do to you, my beauty»), testify to the fact he has decided to proceed to the «final solution of the Ukrainian question.» As more and more evidence of the atrocities committed by the Russian military in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine is revealed, it becomes clear that this was not a drunken orgy of violence and not the excesses of the performer, but a planned terror, which involved the Wagner PMC and specially trained punitive units, that the bombing of entire Ukrainian cities along with their inhabitants is not due to recklessness, but to criminal intent. As the perpetrator of the genocide of the Ukrainians unfolding before our eyes, Putin inherited the precepts of his spiritual father Zhirinovsky, who threw nuclear bombs around with ease in his incendiary speeches.

Beware: postmodernism!

And here the main question arises: how is it that Russia, with its advanced urban class, its developed public sphere, its long history of free media, its historical experience of violence and sensitivity to the word had been quietly observing the birth, formation and institutionalization of the very real, textbook fascism? Why did Vladimir Zhirinovsky's xenophobic invectives pass as comic verses rather than criminal offenses?

The answer, apparently, is that the new Russian authoritarianism, followed by a fascist dictatorship, was born in the bosom of the postmodern 1990s. Caught in the cultural context of the fin de siècle, with its painless fall of the Berlin Wall, followed by the Soviet Evil Empire, which turned out to be made of cardboard like the scaffolding in the finale of Nabokov's “Invitation to an Execution”, with its «end of history» and «a world without borders,» with quotations from Derrida («there is nothing outside the text») and Baudrillard («There was no war in the Gulf»), with Pelevin's novels and the newspaper Segodnya's culture section - Russian politics was being shaped as a game show, where it is impossible to die in earnest.

The new Russian authoritarianism, followed by a fascist dictatorship, was born in the bosom of the postmodern 1990s

It was against this background that Vladimir Zhirinovsky's political theater became possible. Enlightened society looked upon him with a mixture of horror and admiration, just as it had read, for example, the novels of the Marquis de Sade with their edifying torture, the plays of Antonin Artaud's Theater of Cruelty, the physiological stories of Jean Genet - all of which were just then entering the cultural mainstream. Many people liked how easily he crossed boundaries, how deftly he worked with taboo subjects, how he managed to aestheticize violence. Observe the destructive role that postmodernism played in the unprepared public consciousness of Russia, which had accepted it with provincial enthusiasm: it justified the forbidden (such as the base instincts of the crowd), it blurred moral evaluation (it is awkward to talk about ethics when everything is a game), it brought to the political stage the most grotesque forms of paleo-conservatism and neo-Stalinism: from Dugin and Prokhanov to Limonov to Zhirinovsky, all dancing at Satan's postmodernist ball!

On the other hand, Zhirinovsky's buffoonery was in demand by the siloviki and, increasingly, by the Kremlin. They saw it as a useful technology for channeling resentment, right-wing radicalism and proto-fascism, and marginalizing it in Zhirinovsky's traveling circus (the politician liked to tour the country by train, gathering crowds in towns and cities; in the capital he liked to perform near the Sokolniki metro station, pronouncing long monologues about the international situation, just like Fidel). He gathered 10 to 15 percent of the vote in the LDPR's electoral niche (his 23 percent in 1993 was his finest hour) which shrank gradually year after year.

Meanwhile, the law enforcement agencies launched a real manhunt for those who were ready for real political action in that sector - Russian nationalists and right-wing radicals. While Zhirinovsky entertained the crowd with his escapades, the FSB and the Interior Ministry, including the «E» Center especially created for the occasion, completely cleared out the extreme right wing of the political spectrum and followed it up with by suppressing forms of political activism. Later,after the Bolotnaya Square protests they began targeting the liberal segment, the protest of «angry citizens,» numerous zones of civil mobilization and activism. In pursuit of real and fictitious radicals, the security services created a different type of radicalism, far more terrifying and resource-backed - a self-excited machine of state terror, which knows nothing else but how to fight others: gays, liberals, «national traitors,» Islamists, Jehovists, considering them as their fodder base. Fascism matured where it was not expected. A fundamentally new type of person entered the barren political arena - the Orthodox Chekist with a volume by Ivan Ilyin. A fundamentally different political era began, in which we now live.

The New Frankenstein

The crux of the problem is that Zhirinovsky's sectarian fascism, created by the state security apparatus, and fed from the Kremlin's hand, restrained by neither civil society nor the political and judicial systems, turned into a political routine, morphed into a discourse of power, merged with the repressive-power machine, became its ideology and motivation. The ideas of imperialist revenge melded with the police apparatus and military might of Russia, strengthened over the last 20 years, and gave birth to the Frankenstein monster: state fascism. This is the same «new fascism» that Judith Butler wrote about: firstly, it legalizes the «freedom to hate» and, secondly, it mobilizes resentment in order to evoke in people a sense of infringed national greatness. The official propaganda mouthpieces of today broadcast the same ideas of Zhirinovsky - but they already use them to justify the murder of Ukrainians. The eccentric politician's wild fantasies about global revenge, restoration of the Soviet Union, and the destruction of Ukraine have evolved from simulacra, rhetorical figures, and political technologies into Grads, Tochka-Us, and cluster bombs that are now raining down on Ukrainian cities.

Wanton fantasies about restoring the USSR turned into Grads, Tochka-Us, and cluster bombs

The politician himself did not live to see the triumph of his fantasies: he fell ill with coronavirus at the beginning of February, was put on a ventilator due to pneumonia, and at the very beginning of the war, on February 26, was put into an artificial coma. His subsequent biological existence is lost in speculation and rumor - some say he had regained consciousness, read the news and even «worked with documents,» others say that, without coming out of his coma, he died on March 25 (a rumor that was quickly reported in the Duma by his fellow party member Alexander Pronushkin), and his body was kept in a morgue for two weeks so that Putin could bid farewell to it - for no one, alive or dead, would dare approach the sovereign without a 14-day quarantine. This type of conspiracy theories («the reports of my death were greatly exaggerated,» as Mark Twain joked) was in keeping with the comic persona of the deceased.

Vladimir Putin's demonstratively personal and even, I dare say, intimate farewell to his namesake Zhirinovsky - not only the guards of honor but also the Russian banners were removed from the hall - emphasized once again the unique role that the deceased played in the president's life: the last time Putin bade such a heartfelt farewell was in St. Petersburg in August 2013 when his first judo coach, Anatoly Rakhlin, died; that time, too, overcome with emotion, he escaped his guards to walk alone down the deserted Vatutina Street. We thought Zhirinovsky was the Czar's favorite jester, but he was also his mentor, teacher, and sensei. The body of the LDPR leader was decontaminated and buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery, but the virus of fascism and Zhirinovsky's cause live on. As we all live today in a post-apocalyptic world invented by Vladimir Zhirinovsky.