“Hello. My husband is a convict and has enlisted as a volunteer in the Wagner PMC. Help me bring him back.”

“We could try. You’ll need to write a request.”

“Is that really necessary? I’m afraid of making things worse.”

And with that, she is gone. She might resurface in a while:

“They told me he'd been killed in action and that his body had not been retrieved. I want to bring his body back.”

The specialists of Russia Behind Bars offer their short condolences and reply that the repatriation of bodies from a war zone is outside their domain. If I hear such requests, I take the time to explain: “Your husband was a war criminal. He volunteered to take up arms against a neighboring country that did not attack us.”

You might say it’s harsh and cruel. You might even be right.

Rumor has it that military recruitment in prisons is not voluntary. We have been monitoring the recruitment situation in penal colonies since the beginning of the war. Volunteers abound. Inmates are lining up to go to war. Their friends and relatives write: “Where do I apply for him to get recruited sooner?”

If we were to dig deeper into their motivation, we could conclude that there is an element of coercion. Russian prisons are notorious for torture, abuse, and humiliation. For many inmates, volunteering to go to war is a way out. Anything is better than the inside.

As for relatives, they are mostly after money. Eight out of nine questions we get deal with compensation. “Will they really get paid? When is the payday? Why haven’t they sent the contract? How much will he get if he is wounded? What if it's a serious injury?”

For many inmates, volunteering to go to war is a way out. Anything is better than the inside

A few women are still fighting the system to get their partners back to correctional facilities. Our first case was the fastest and the most efficient.

The man was an ordinary inmate in Yaroslavl Region, convicted for assault causing grievous bodily harm. A so-called “goat” in the prison hierarchy, meaning that he cooperates with the colony administration.

By contrast, his wife, also a former inmate, was a “zhuchka”, which is a higher status on the inside. It means that she never caved in or snitched on other inmates to make her own life easier or win someone's favor. Her marrying a “goat” did not count because the rules on the outside are different.

So this zhuchka came to us for help. Her husband had been recruited, even though he had served almost all of his sentence. They had two children, with the younger barely out of nappies. Her request was the first of the sort, and while we were busy writing a guide, she did not waste time and visited him in prison. She did great without any instructions, putting her husband's head in the right place. She might have given him a whack or two on the head – that’s a zhuchka for you. One way or another, he withdrew his application. There were no consequences because volunteers were coming in droves.

We also had another memorable case a little later, when we already had all the guides in place. Anna used our guide and succeeded. Her husband, who had already been recruited, managed to stay in the colony, and the entire colony was left alone.

I spoke to her afterward.

“Anna, I really admire what you did. You did the right thing. You started fighting for your husband right away. What was your main motivation, by the way?”

“I don't want him to enlist in a private military company. Nothing doing! Private contractor. Now, a government company, that's a whole other story.”

Normally, I never have to search for words, but my work has rendered me speechless more than once lately.

How it began

It began back in February. Even before the war, mind you. Inmates in the Rostov Region started saying they were being transported somewhere on a massive scale, allegedly because the colonies needed renovation. It was strange because the barracks had just been built – with the inmates’ relatives’ money, as usual. No Rostov Region colonies were purchasing any construction materials on the government contract website.

Then the war broke out. Two of the colonies that had been vacated were used for keeping prisoners of war. Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) officials gave way to the military police and the FSB.

Around the same time, we started receiving alerts from the colonies for former FSIN and law enforcement officers. Convicted SOBR and OMON special police officers, prosecutors, investigators, customs officers, and prison guards are kept in specialized penitentiary facilities to secure them from the general prison population. Recruiters visited two such facilities: near Ryazan and near Nizhny Novgorod. There are more, but we haven’t heard any accounts of recruitment.

So someone – an unknown entity – came to the colonies in Ryazan and Nizhny to recruit inmates as mercenaries. The convicted law enforcement officers did not waste time trying to figure out who is who and refused outright. They understood full well that war was nothing like rounding up schoolkids at rallies or prosecuting four-eyed highbrows. They are no dummies.

Inmates from among ex-cops refused to enlist. War is nothing like rounding up schoolkids at rallies. They are no dummies

This was in February. In April, we took a closer look at the so-called Chechen battalion, which is keeping a low profile but kept posting endless videos from Ukraine back then. Some of the fighters, ethnic Chechens, still had a long prison term to serve. Admittedly, Chechnya typically considers itself to be above the law. All hands on deck, and god knows who they had recruited there.

Late in June, inmates in the Leningrad Region were approached by the Wagner PMC – so-called “musicians”. New slang quickly emerged: inmates who enlisted said they “joined the band”.

Promises were vague. Recruits signed a medley of papers, nothing standardized. Some recalled submitting consent to join the “DPR” police force. Some said their forms had Russia's Ministry of Defense header and included a checkbox “I agree to go to war in Ukraine”. Those who enlisted said they were promised early release. Or that there would be an amnesty. However, if they got killed in action, this would be considered as “shot during an escape attempt”.

The whole thing looked like a bunch of nonsense.

Early in June, the first group of prisoners, 42 men, were transported from the Leningrad Region to Penal Colony No. 2 (IK-2) near Rostov-on-Don – one of the penitentiary facilities presumably closed down for renovation.

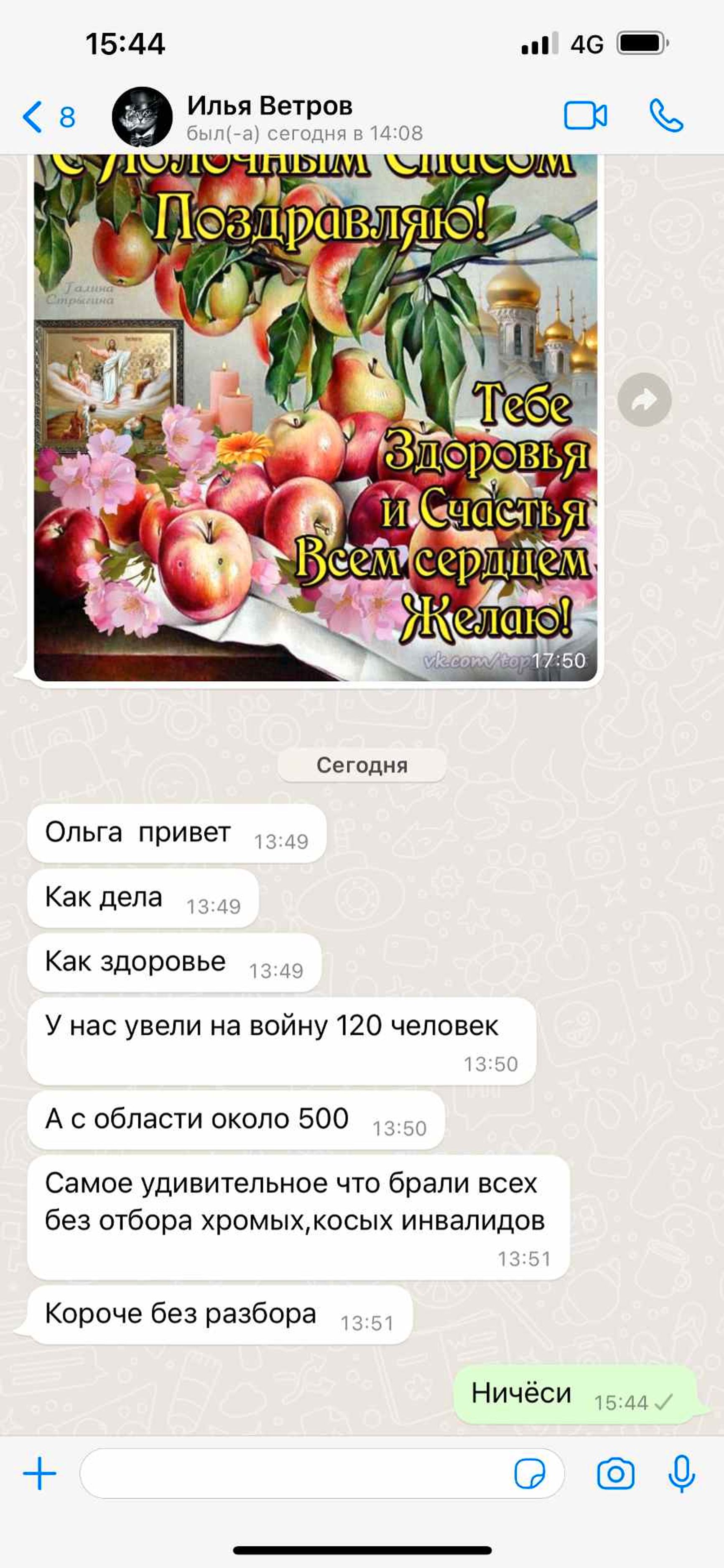

Hi Olga. How are things? How are you feeling? They took 120 of our guys to war. Around 500 from the region. The most surprising thing is they took everyone: the lame, the limp, the disabled. Just everyone. - Blimey.

This was the last where we heard anything from them. They told us they’d donned camo, trained twenty hours a day, and ate dry rations on the go. They received training in mine clearance and – I’m not sure about the correct military term – storming? In a nutshell, former inmates got an express stormtrooper course, even though some of them had never done conscription service.

Further on, the relatives of some other missing inmates submitted inquiries to the FSIN and were told that the inmates had been transferred to IK-12 in the Rostov Region at their own request. “Go look for him there.”

These penal colonies are being used as boot camps.

The initial plan was to train the recruits for two weeks, but the “first wave” of inmates joined combat as early as on July 14, presumably missing out on the last couple of days of training. This was the battle [pro-Kremlin director] Nikita Mikhalkov glorified in his Besogon TV show, narrating the heroic death of Konstantin Tulinov, who was said to have blown himself up with a grenade along with three Ukrainian soldiers to avoid captivity.

The inmates of Yablonevka (IK-7) in the Leningrad Region learned about the death of “Kostya the Red” (Tulinov's alias on the inside) a few days after the battle, long before Mikhalkov’s pompous story. As they recounted, the guards lined them up and the warden Alexander Rulev informed them about Kostya the Red's demise and the injuries sustained by a few other “colleagues”. A wounded inmate's wife got to talk to him on a video call. She also saw some medical papers and gleaned that her husband was in the hospital under an alias, not his real surname.

As Mikhalkov claimed in his television show, Konstantin Tulinov had misstepped but washed off his dark past with blood. He did not expand on the particulars of said dark past – and for a good reason. Tulinov had several convictions, actively cooperated with the colony administration, and got his last prison sentence for extorting money from his cellmates. In other words, he ran a so-called “torture cell” (which is impossible without the warden knowing or even benefiting) but overplayed his hand. Mikhalkov also said Tulinov had been pardoned posthumously, but the Russian Federation does not have the legal mechanism for that. The President's website features a section on pardons granted, but Tulinov is not on the list, and neither are any of the inmates sent to Ukraine, whether they are dead or alive.

Mikhalkov also said Tulinov had been pardoned posthumously, but the Russian Federation does not have the mechanism for that

In the meantime, Wagner agents left the Leningrad Region for the neighboring Novgorod Region even before the first unit of ex-inmates engaged in combat. In one of the colonies, inmates happened to film a helicopter with the Wagner PMC logo on the hull taking off from the grounds.

Since then, we have been receiving accounts of mass recruitment of inmates from all over the European part of Russia except the Kaliningrad Region (apparently its geographic isolation impedes the logistics). In early August, the PMC made it to Tatarstan. Around the same time, we started to receive reports about recruitment at pretrial detention facilities: in the Moscow Region, a theft suspect (nothing serious) was quick to enlist because he was promised his case would be dropped. He went to war, returned shell-shocked, and ended up in the same detention center. His case had been suspended but was reopened again. Tough luck.

Convicts in many colonies wrote to us that “Prigozhin, Putin's cook, visited them in person”, in these exact words. It was hard to believe, but such reports were numerous and some of the witnesses would have certainly recognized the man. The details in different accounts from different colonies also matched, and some of the inmates assured us they spoke to Prigozhin himself (the editor's office has transcripts of such conversations). Many said that the man who strongly resembled Prigozhin had had the Hero of Russia order on his chest, although there has been no official information about Prigozhin’s conferral.

Promises made

Eventually, we figured out what kind of papers Wagner recruits sign when enlisting and what promises they get.

Let's start with the paperwork. Inmates write two documents: a request for transfer to the FSIN Directorate for Rostov Region for serving the rest of their sentence and a petition for pardon to the President. Naturally, none of the documents have any legal force when it comes to sending convicts to war.

The legal status of recruited inmates remains unclear. And so do the grounds for them leaving the penitentiary facilities where they were placed by the court’s decision. Interestingly, the courts are largely ignoring these developments, while the Prosecutor’s Office, including its department supervising compliance in the penitentiary system, is carefully looking the other way. And keeping mum.

There has been a single response, however. After asking the warden of Yablonevka (IK-7, Saint Petersburg) where and on what grounds a certain inmate from among Wagner recruits was transferred, a Russia Behind Bars attorney was summoned to the Investigative Committee in Moscow under the pretext of a different case. In a one-on-one meeting, the investigator told our attorney in so many words: “The adjacent agency (that's what they normally call the FSB) asked me to let you know: if you continue down that road, you’ll end up picked off the street with ten years worth of drugs.” Shortly after, his client, the recruited inmate who was already wounded and was in hospital in the Luhansk Region, received direct threats from Wagner PMC agents, who told him that his relatives must drop the legal aspect of his recruitment if they didn't want to put him in trouble. They did not specify, but the recruit concluded that they would just shoot him. The verb “zero out” was also used – a common modern equivalent for “kill”.

In fact, threats of shooting recruits on the spot are part and parcel of the standard “terms and conditions”. Wagner agents make the same promises to all recruits. They start with the “carrots”.

The carrots:

– A monthly income of 100,000 rubles (~$1,650) in cash and a 100,000-ruble bonus, to be paid to the recruit directly or to their family. No papers are issued to recruits’ relatives.

– 5 million rubles (~$82,300) to their relatives in the event of death. Several such compensations have already been paid out. Far from all, but it’s been known to happen.

– Compensation for wounds received in action (the amount is not specified). Those seriously injured can expect to return home with their conviction annulled. We have not heard of such cases yet.

– In a few colonies, recruiters promised to reward acts of outstanding heroism by arranging the visit of the recruit’s mother or wife – who would arrive by plane, no less. Such fantasies do not require any comment.

– After six months of participation in the special operation (starting from the first combat experience, not the date of recruitment), inmates would walk free, have their criminal records expunged, and get the President’s pardon.

The sticks:

– Execution on the spot for attempted desertion or surrendering to the enemy. This is indirectly confirmed by the accounts of both recruits and Wagner mercenaries: former inmates are followed by an anti-retreat unit consisting of “seasoned fighters”.

– Execution on the spot for consuming drugs or alcohol.

– Execution on the spot for looting. (Interestingly, the long-time residents of occupied Donetsk and Luhansk regions, with whom I often talk for work and just chat, have very fond memories of Igor Strelkov-Girkin for this particular habit of shooting looters on the spot without trial. My weak protestations about possible mistakes and the need for investigation and a fair trial were met with a shrug).

Finally, considering that Russian law prohibits mercenaries and that the Wagner PMC seems to be thriving, its commanders might sooner or later wonder why they should pay anything to inmates. Inmates come with an expiration date. Let them fight, for sure, but once the payment is due, you could always shoot them. “You abetted looting!” Such accusations are hard to disprove.

On August 16, an amateur ad featuring newly recruited Wagner fighters from among inmates appeared on Vkontakte. The main message was that they were not cannon fodder and were generally having a great time. The first man in the video is convict Mikhail Shpakovsky from IK-7, Pankovka, Novgorod Region. He worked as a fireman on the inside and died in combat five days after the video was posted.

Only around 10% of the inmates who joined the fight in mid-July have survived to date. There is no telling what will happen to the seriously wounded. We are following some of them, for instance, a Semen Palchevsky, also from Pankovka. He had his arm torn off and underwent treatment in a hospital in Luhansk. He was among the first to be so gravely injured. We haven't heard from him lately. He isn't at home or in prison either. His whereabouts are unknown. If they show us a Palchevsky who is sitting in IK-7, safe and sound, going nowhere, it’s in fact Semen Palchevsky's father. They are a dynasty.

Today

By the most careful estimates, private military companies (Wagner is only one example) have recruited around 5,000 inmates. Not all of them are fighting; some are still training, while others are waiting for their turn in penal colonies because there are more volunteers than needed. Some are already dead.

All that considering that PMCs have only processed the penitentiary institutions of the European part of Russia. Inmates have shared that Wagner agents or Prigozhin himself mentioned plans of recruiting 20,000 convicts, or even better, 50,000.

Will they succeed? They certainly will, if they venture further east, beyond the Urals and into Siberia.

A man who looks like Evgeny Prigozhin tells inmates: “I've promised the President I will win this war.”

It appears to be true. Indeed he has. And it had to be to the president

because no one else in Russia, even the Security Council secretary Nikolai Patrushev or the FSB director Alexander Bortnikov, not to mention such a small fish as the head of the FSIN, has the power to remove so many inmates from the legal environment.

Can you imagine? A helicopter owned by a private company lands in a restricted facility –a maximum-security or even a “special regime” prison, where there are no random people. Its passengers simply elbow the guards and the warden out in front of the inmates. They occupy the offices, grab personal files, and bring in the polygraph, which is an essential component of interviews, along with questions about the attitude to Ukraine.

Then they simply take some of the inmates away. Put them on a transport with nothing but a change of underwear and two packs of cigarettes. And that’s it. “You’ll be given all you need,” they say.

They simply take some of the inmates away with nothing but a change of underwear and two packs of cigarettes

Prison guards are bound to realize things might soon get tough for them. They know they’ll be the ones to take the fall. In theory, they are responsible for inmates’ lives and health (in practice, not so much), so if something happens, it will be their fault. What explanations can they provide? That a bald guy in a blue helicopter came and took whoever he wanted?

What about the court’s decision?

What about terms to be served?

The re-education, rehabilitation, and reintegration of a society member into society?

Where’s said member?

Prison administrations understand perfectly well that the policy may change tomorrow, and then what? Who will become a scapegoat? The prosecutors also realize that. So does the FSB.

None of them want the policy to change.

For that, they only need two things: an eternal Putin and a never-ending war.

The military have it easy. They’ve done nothing wrong. Whatever you ask them, they say they had nothing to do with it. “We have no convicts. We know nothing. All the best, your Ministry of Defense.

We have no idea who's in charge of the army, and you want us to take the rap for Wanger. We're nobody’s fool.”

Hard to beat that.

Meanwhile, rumors are spreading that not all ex-prison recruits are volunteers. There was a 28-year-old guy in a penal colony outside Tula, a former EMERCOM officer, in great physical shape. He was in for murder, which means Wagner agents were all over him like flies on honey: they love murderers. However, our EMERCOM guy didn't want to go to war. He’d served half of his sentence (11 years) and had a good wife and three kids waiting for his release. He refused outright.

Meanwhile, rumors are spreading that not all ex-prison recruits are volunteers

His wife recently learned they’d taken him anyway. They didn't tell her until he was gone and didn't even allow a phone call. His fellow inmates who managed to talk their way out of recruitment told her in secret that her husband was pressured.

She is now trying to bring him back. We’re doing what we can to help. I have faith in them. She is a strong woman with a big heart. His strong physique was his downfall.

Without it, getting off is easier. We also had another zhuchka – a former inmate who had not cooperated with her guards. Her beloved was doing time in Ukhta and was silly enough to volunteer. When he called her with the good news, she came running. Told him to withdraw his petitions and requests and to stay put.

“But they said they’d zero out my term for that!”

“If you don't, I’ll zero you out myself. Right here, right now!”

So he did. And he is staying put, with no one is pressuring him.

His lady must have quite a reputation.