On May 22, Pentagon spokesperson Patrick Ryder stated publicly that it was “likely” Russia had launched an anti-satellite weapon into low-Earth orbit. The development came just a month after Russia blocked a U.S.-Japanese resolution in the UN Security Council on the non-deployment of nuclear weapons in space. Since Moscow has traditionally opposed the militarization of space, the U.S. took Russia’s veto as a possible cover-up. According to Maxim Starchak, a research fellow at the Center for International and Defense Policy at Queen’s University (Canada), the Kremlin has every incentive to engage in such behavior. However, the resources available to Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos, are so limited that the veiled threats are more likely aimed at affecting negotiations than at waging war in the cosmos.

No country on Earth can compete with the space-based capabilities of the United States military. America’s constellation of satellites allows for the integration of combat intelligence, communications, and navigation systems, enabling Washington’s land, sea, and air forces to coordinate operations among themselves.The U.S. possesses approximately 240 military satellites, while Russia has just over 100, and in terms of the total number of satellites, the gap is colossal: 5180 against 180.

The massive imbalance is easily explained by the difference in production capabilities between the two countries. While the U.S. can build approximately 3,000 spacecraft a year, Russia can only produce 40.

The U.S. possesses approximately 240 military satellites for various purposes, while Russia has just over 100

In addition, the U.S. can use commercial and civilian satellites as part of its military operations, and satellite imagery from American private companies has been a great help for Ukraine in its war against Russian aggression.

Why the Russian-Chinese treaty against weapons in space does not work

Russian nuclear doctrine considers the creation and deployment of missile defense and strike systems in space to be a threat, as Moscow fears that Washington could use its superiority in outer space to launch an unstoppable attack on Russia's strategic forces.

To combat this threat, in 2008 Russia and China submitted a proposal to the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva: a draft Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects (PPWT). At the time, the two countries could not rival America’s financial and technical capabilities, meaning that a blanket ban on weapons in space represented their only opportunity to limit U.S. military superiority in that domain.

Putting forward the diplomatic initiative to ban space-based weapons systems, Russia nevertheless asserted that the development of terrestrial anti-satellite systems should not be outlawed. In other words, Russia and China sought both to limit the presence of U.S. military systems in space and to continue developing their on-the-ground anti-space systems. The proposal was unrealistic, of course.

The draft treaty had other shortcomings as well, including its vague definition of what should be considered a “weapon,” especially given the abundance of space-based systems used for military navigation, communication, monitoring, and command and control. In addition, the draft did not provide for the verification of the treaty’s implementation. As a result, the initiative was not given serious consideration.

Russia and China attempted to revive PPWT deliberations by presenting an updated draft in 2014, but they found no support from the United States. Later discussions have led only to the parties exchanging political commitments not to place weapons in space first, while also voicing calls for transparency.

In the meantime, China began to actively develop its space program, outpacing Russia in all core parameters and becoming second only to the U.S. In the future, the Chinese program is set to include more advanced navigation, communication, and reconnaissance systems that can support military operations from space. Since China cannot deploy these systems without also taking measures to ensure their security against attack, the value of PPWT for Beijing is declining.

China began to actively develop its space program, outpacing Russia in all core parameters and becoming second only to the U.S.

Obsolete Russian satellites

Although Russia has several space-based military systems that support the operations of its armed forces, none of them are operating at full capacity. The country has no radar imaging satellites, and only a limited number of photo satellites, with some of them expired. The Russian data relay satellite network, which can transmit images from reconnaissance satellites during the long periods when they are not in sight of ground stations, is also limited.

No wonder Dmitry Rogozin, then the head of Roscosmos, used outdated satellite images when making veiled threats against NATO in advance of the alliance’s 2022 summit in Madrid. One day before the opening of the event, the Roscosmos Telegram channel published a collection of images showing “the summit site and those very ‘decision-making centers’ supporting Ukrainian nationalists.” The images were labeled as if they had been taken recently by a Russian “Resurs-P” satellite; however, all of Russia’s “Resurs-P” satellites were out of commission at the time.

Russia’s space launch crisis further complicates its situation. Maintaining even limited constellations of spacecraft requires multiple launches, but Russia has carried out only 15-26 launches per year for the past eight years, far fewer than the United States or China. In 2023 alone, the U.S. had 109 successful launches, China had 66, and Russia had 19.

In 2023 alone, the U.S. had 109 successful launches, China had 66, and Russia had 19

Another major constraint is weak ground infrastructure. Although Moscow can put a group of military satellites into orbit, not all Russian military complexes can receive the signals they send back. Russia's space capabilities are generally poorly incorporated into its armed forces' command structure, making it difficult for Russian troops to benefit from them. Commanders have no understanding of how to leverage space-based assets and no technical or organizational prerequisites for their use. In addition, Russia’s shortage of satellites is compounded by the fact that its spacecraft are capable of staying in orbit for only half as long as their American counterparts, according to expert estimates.

In light of the above, Russia has a greater motivation to shoot down enemy satellites that the U.S. — or even China — does. That is precisely why Moscow is developing anti-satellite weapons, and why Washington is right to fear them. Proposals from Russian political and military experts only suggest a desire for further escalation.

Soviet-era innovations

In March 2018, less than three weeks before Russia’s presidential election, Vladimir Putin addressed the country’s Federal Assembly. After more than an hour of largely forgettable domestic policy talk, the topic shifted to defense, and the videos soon began: largely computer generated demonstrations of the supposedly groundbreaking Burevestnik cruise missile and Poseidon nuclear torpedo. However, the development of both projects began in Soviet times, and the same is true of Russia's space-based nuclear weapons.

In Washington, as part of a recent hearing before Congress, Pentagon representatives expressed concern about nuclear weapons and the potential for a nuclear explosion to be set off in Earth’s orbit. U.S. media sources familiar with the intelligence behind the statement clarified that the matter at hand concerns a nuclear weapon — and not a nuclear facility, as was previously thought. We still do not know what kind of weapon it may be, but in order to get a better idea of the range of possibilities it is instructive to examine two Soviet programs, the SK-1000 and the SP-2000, developed in the 1980s as a response to the U.S. Strategic Defense Initiative (a.k.a. “Star Wars”).

The SK-1000 aimed to create a space-based missile defense echelon using satellites to engage a target orbiting Earth or a target descending from orbit into the atmosphere. This was to be accomplished by creating a sort of ballistic silo rocket that would first launch satellites into space, then use them to defeat enemy vehicles.

Russia is currently known to have a similar anti-satellite program called Burevestnik (not to be confused with the missile of the same name). As in the Soviet Union, the program creates maneuvering interceptor nanosatellites that are launched into orbit by a special rocket. Presumably, the purpose of Burevestnik satellites is to attack vehicles both in low-Earth and geostationary orbit.

The specific technology of engagement is unknown, but the construction of the satellites provides for the use of both a conventional explosive charge and a nuclear warhead.

Another Soviet-era space project of note is the air-based anti-satellite complex Kontakt, which comprised MiG-31D aircraft and 79M6 Kontakt missiles and was intended to shoot down enemy vehicles in low-Earth orbit. The project was closed in the 1990s before being resuscitated in 2009, and while its initial design provided for the use of a kinetic interceptor, there are no technical limitations that would prevent the system from using a nuclear payload.

The dangers of nuclear weapons in space

The main problem with nuclear weapons in space is that a nuclear explosion there would have indiscriminate and long-lasting effects. Some satellites could be damaged in the direct explosion. Others would suffer damage from the electromagnetic pulse of the explosion, as the vast majority of satellites are vulnerable to electromagnetic pulses and radiation.

The explosion would immediately leave behind an environment with high radiation levels, causing unprotected satellites in the affected orbit to lose functionality more quickly than normal. Such an explosion would affect all military, civilian, and commercial satellites operated by governments and companies around the world.

A nuclear explosion in space would affect all military, civilian, and commercial satellites

Two years ago, Russia’s then Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Borisov said his country was developing kinetic and directed energy weapons. Although he provided no specifics, he may have been referring to kinetic interceptors for satellites in orbit, or to nuclear directed-energy weapons.

Nuclear directed-energy weapons use a nuclear explosion to power the active medium of a laser, thereby turning it into a generator of electromagnetic radiation that disables the radio-electronic and optical elements of spacecraft. A directed-energy weapon is considered to be more practical in space than a nuclear warhead because it could be aimed more precisely, affecting onboard computers or blinding satellites without causing indiscriminate damage.

Some experts have speculated that the Russian laser system Peresvet, which has been put on combat standby duty, could be using the energy of a nuclear explosion to blind optical reconnaissance satellites. This hypothesis is yet to be confirmed, but Russia has possessed designs for such weapons since the 1950s.

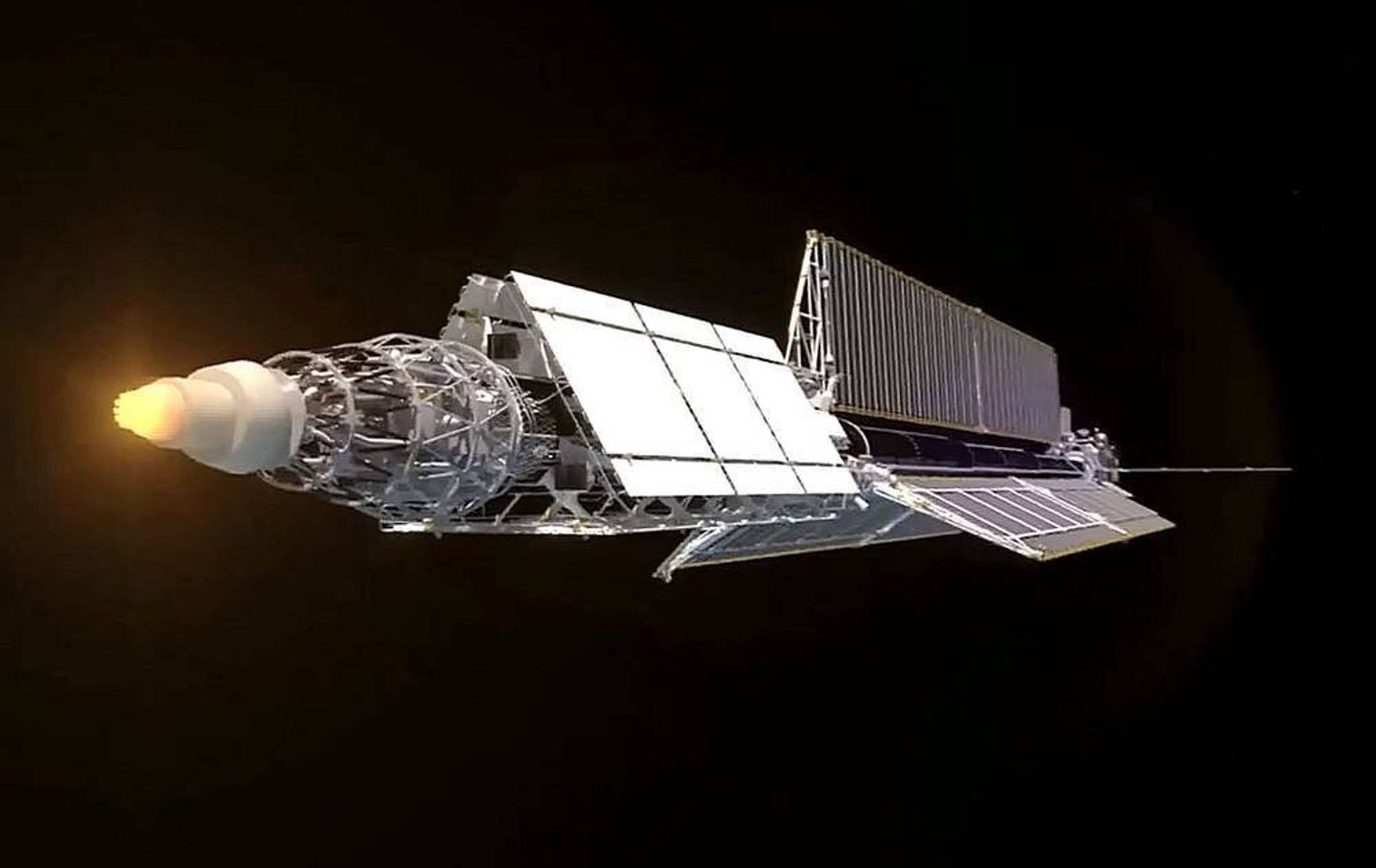

In addition to the nuclear option, the state-owned Russian news agency RIA Novosti has written, Russia's Zevs space tug can also disable satellites.

The Zevs (“Zeus”) nuclear space tug

More bark than bite

And yet, whether the Russian military-industrial complex is capable of delivering such weapons remains a major question. Despite large budget expenditures, its capabilities remain limited. Roscosmos has long suffered from low profitability, accumulated debts, and mounting losses. After Russia’s limited invasion of Ukraine in 2014, the U.S. imposed sanctions against certain Roscosmos enterprises. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, many of Russia’s international partners withdrew from what international contracts remained. As a result, limited access to Western technology, components, and financing brought additional costs to Roscosmos enterprises and caused them to postpone the fulfillment of their obligations.

Financial gaps led the corporation to cut its staff and seek new partners among developing countries like Algeria and Egypt. Last year, Russia's space corporation entered the borrowing market for the first time, issuing $112 million worth of bonds.

Although Vladimir Putin advertised the Burevestnik and Poseidon weapons systems way back when he was still just a three-term president, there have been no further demonstrations — let alone documented tests. Nevertheless, Putin's public statements on the possibility of placing nuclear weapons in space represent another escalatory step aimed at convincing the United States of Russia's superiority in armaments, thereby allowing the Kremlin to secure more favorable negotiation terms.

Putin's public statements on the possibility of placing nuclear weapons in space are another escalatory step

And his words have had at least some effect, as the Biden administration has already expressed its willingness to discuss with Moscow the topic of nuclear weapons in space even as Russia’s war against Ukraine rages on with no end in sight.

However, the Russian Foreign Ministry is ready to negotiate on strategic stability only if the United States changes its policy toward Moscow, stops supporting Ukraine, and agrees to discuss other areas of Russian interest, namely: NATO expansion, missile defense, and the proximity of U.S. and other alliance members' weapons to Russia's borders. In other words, the United States would have to accept the ultimatums Russia outlined in December 2021, before the full-scale invasion — an unrealistic scenario on all counts. The Kremlin understands this, of course, and is prepared to wait for as long as it takes — even if it takes generations for politicians in charge to change.