Just days before Donald Trump’s inauguration, the presidents of Russia and Iran signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Treaty, emphasizing cooperation in the security sphere. Given Trump’s tough stance on Iran, Tehran may see its deepening relationship with Moscow as a shield. Russia, for its part, solidifies ties with one of its few remaining allies. Yet this alliance carries significant risks for its signatories. By combining their forces, both nations may find themselves expanding their list of adversaries. Adding to the challenge, the partnership is clouded by mutual distrust, as both sides remain wary that the other could defect to the opposing camp at the first opportunity.

An alliance of necessity

On Jan. 17, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian signed the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Treaty, replacing a 2001 agreement on the principles of cooperation and mutual relations. The new agreement covers various sectors, including defense, counterterrorism, energy, finance, transportation, and industry.

“We are united in our determination to build on our achievements and elevate our relationship to a qualitatively new level. That is the essence of the treaty we signed,” Putin stated.

He highlighted economic cooperation as a key focus of the negotiations, noting that Russia and Iran are essential trade, financial, and investment partners for each other. Putin pointed out that trade turnover between the two countries grew by 15.5% in the first ten months of 2024. According to Kremlin documents shared with the media ahead of the Iranian president’s visit to Moscow, trade turnover from January to October 2024 reached approximately $3.77 billion, with total trade for 2023 exceeding $4 billion. Over 96% of mutual transactions are conducted in national currencies.

The dramatic growth in trade and economic cooperation began in 2022, after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Facing harsh Western sanctions, Moscow pivoted sharply toward the east. Iran, long accustomed to life under sanctions, had little choice but to align itself further with Russia. Together, the two nations seemed destined to form an alliance of necessity.

The dramatic growth in trade and economic cooperation began after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine

Their cooperation within the Eurasian space is also advancing. The day after Putin and Pezeshkian met at the Kremlin, it was announced that the Eurasian Economic Union and all its member states had completed the procedures required to bring the free trade agreement with Iran into force.

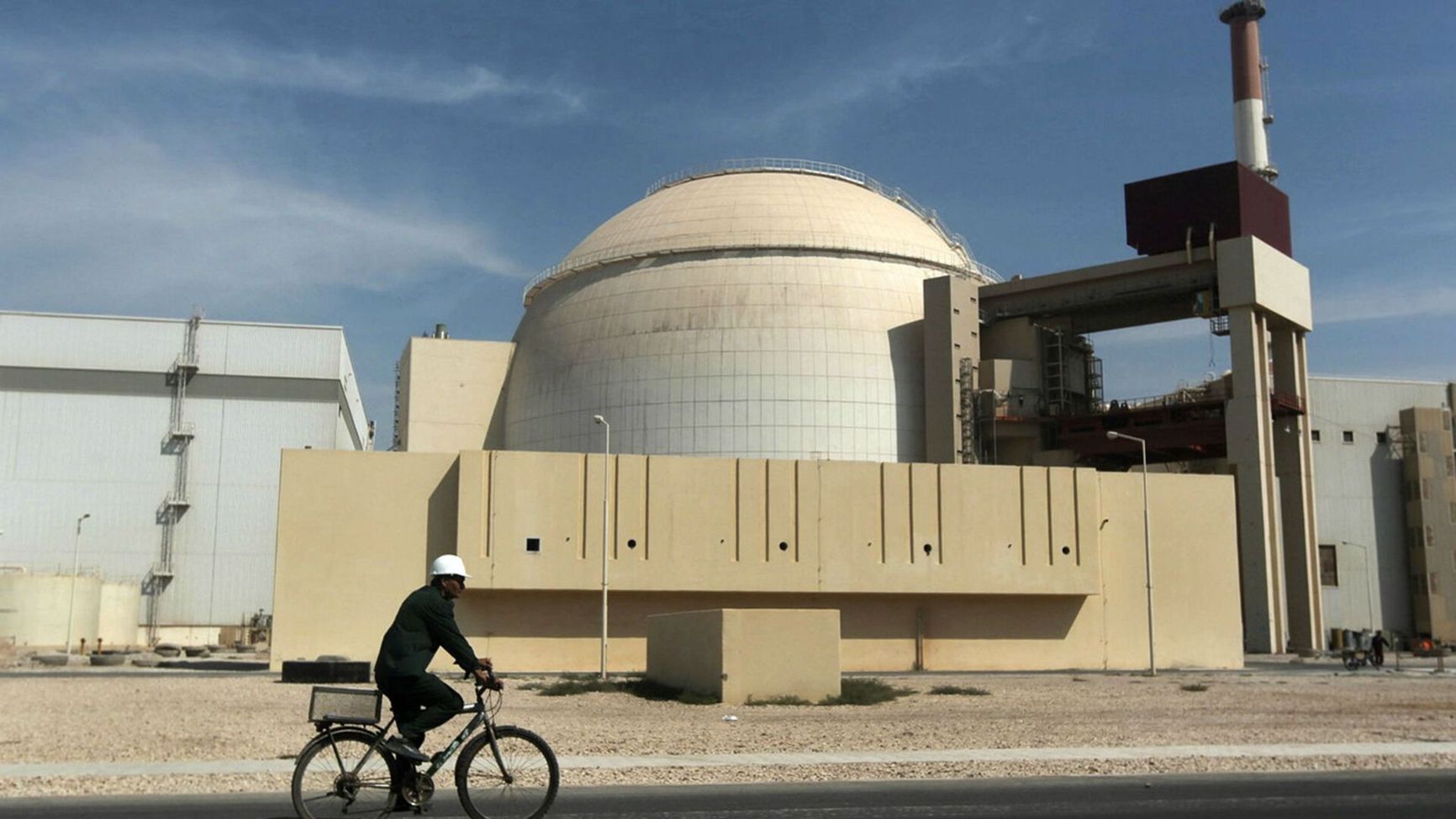

One of the key joint projects between Russia and Iran is the North-South corridor, which connects Iran to Russia and, from there, to Europe and Asia. Once completed, this corridor will shorten trade routes between the two countries and reduce costs. Cooperation in nuclear energy is also actively developing. Iran hopes Russia will continue assisting in the construction of nuclear power plants, with negotiations on this topic planned soon with Rosatom.

Meanwhile, construction of the second and third units of Iran’s Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant is ongoing. Completion is scheduled for 2025 and 2027, respectively, though these timelines may be delayed due to payment difficulties — a recurring issue in bilateral relations, as Putin noted during the press conference with his Iranian counterpart. Cooperation in other areas continues to progress as well.

The Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant

The need for a new treaty was first raised by former Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif during his visit to Moscow in the summer of 2020, although some Iranian sources claim that work in this direction had been underway since 2014. Either way, the process became bogged down in bureaucracy. In the meantime, Iran signed similar agreements with China (March 2021) and Venezuela (June 2022), while Russia reached agreements with North Korea (June 2024) and Belarus (December 2024). However, the latter did not concern strategic partnership, but rather security guarantees within the framework of the Union State (founded in December 1999).

The contents of Iran’s agreements with Beijing and Caracas remain unknown, but they are believed to be fairly general in nature, aimed at fostering cooperation across a wide range of areas, as is typical for such documents. Russia’s agreements, however, are more specific. According to the text of the treaty signed with North Korea, one party is obligated to provide immediate military assistance in the event of an armed attack on the other. The treaty with Belarus entails the use of all available forces, including Russian tactical nuclear weapons stationed on Belarusian territory, to protect the sovereignty of the Union State against external aggression.

Against this backdrop, the strategic alliance between Russia and Iran has naturally raised concerns in the United States, the European Union, and Arab countries. However, Tehran was quick to point out that its agreement with Moscow ought not be compared with Moscow’s agreements with Minsk and Pyongyang. “The nature of this agreement is different. They [Russia, North Korea, and Belarus] have established partnerships in areas we have not particularly addressed. The independence and security of our country, as well as reliance on our own capabilities, are of utmost importance. We are not interested in joining any bloc. For 45 years, we have paid the price for the independence of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” said Iranian Ambassador to Moscow Kazem Jalali in mid-December.

Both Moscow and Tehran emphasize that their agreement is not directed against other countries — although Sergey Lavrov described the agreement with Pyongyang in similar terms. “This treaty, like our treaty with North Korea, is not directed against any country and is constructive in nature. It is aimed at enhancing the capabilities of Russia and Iran in various parts of the world, enabling them to better develop their economies, address social issues, and ensure reliable defense capabilities,” Lavrov stated on January 14 during a press conference on the activities of Russian diplomacy in 2024.

What Russia was able — and unable — to negotiate with Iran

The text of the treaty, published on Jan. 17 on the Kremlin's website, consists of 47 articles. While it does not mention providing mutual assistance in the event of war, it does contain several noteworthy provisions.

“In the event that one of the Contracting Parties is subjected to aggression, the other Contracting Party shall not provide any military or other assistance to the aggressor,” the document states. Additionally, both sides commit to preventing their territories from being used to support separatist movements or other actions that threaten each other’s stability and territorial integrity. Iran and Russia also pledged not to join any unilateral sanctions targeting the other party, including sanctions against individuals or legal entities.

As for military-technical cooperation (MTC), the treaty uses fairly general language, typical of such agreements. However, it notably emphasizes cooperation and consultations “to counter common military threats and security challenges of a bilateral and regional nature,” as well as the development of MTC. That said, the specifics of what this entails remain unclear.

Between 1992 and 2020, Russia supplied Iran with MiG-29 fighter jets, Su-24MK bombers, Su-25 attack aircraft, T-72S tanks, Mi-17, Mi-171, and Mi-171Sh helicopters, S-200VE surface-to-air missile systems, and also fulfilled contracts for Tor-M1 and S-300 air defense systems.

In November 2023, Iran's Deputy Defense Minister General Mahdi Farahi announced the start of deliveries to the Islamic Republic of Russian Mi-28 attack helicopters, Su-35 fighter jets, and Yak-130 combat trainer aircraft. However, so far, the Yak-130s are the only aircraft confirmed to be in Iran.

Russian-made Yak-130 combat trainer aircraft were delivered to Iran in the fall of 2023

In early January, the Military Watch Magazine website reported that the Iranian Air Force plans to commission Russian “4++ generation” Su-35 fighter jets by the end of 2025. Construction of reinforced facilities to accommodate the planes has already begun at Hamadan Air Base, located 300 kilometers east of Tehran. According to some reports, Iran has become the third-largest importer of Russian weapons, after India and China. The delivery of fighter jets will undoubtedly strengthen Iran's military capabilities, but it is unlikely to fundamentally alter the balance of power in the region, at least in the near term.

Iran has become the third-largest importer of Russian weapons, after India and China

After receiving significant quantities of Iranian drones over the past two years, Moscow has gradually ramped up its domestic production. Analysts estimate current production at around 6,000 units annually, reducing the need for Iranian supplies. Iran still requires Russian military assistance, but such cooperation is unlikely to encompass direct intervention. Russia is suffering from a shortage of manpower due to the war in Ukraine — and perhaps more importantly, Moscow still values its relationship with the Gulf Arab monarchies, particularly the UAE and Saudi Arabia, which can still be counted on to coordinate oil prices and to maintain economic ties with Russia despite Western sanctions. Russia's trade turnover with the UAE reached $11 billion in 2023.

Another critical factor is coordinating Middle East policy with Arab countries. After the fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime in Syria, the Kremlin has found it particularly important to maintain close ties with other egional players in order to counterbalance American influence. Iran also plays a key role in pursuing this strategy.

After the fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime in Syria, the Kremlin needs to maintain close ties with other regional players

Notably, the strategic cooperation agreement between Russia and Iran was signed just three days before the inauguration of Donald Trump, though Moscow denies that this timing was deliberate. “There is a lot of speculation about the choice of date for signing the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement between Iran and Russia right before Trump's administration takes office. It only brings a smile. Let the conspiracy theorists entertain themselves,” commented Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov. However, the coincidence of dates could hardly go unnoticed, especially given the many questions surrounding what U.S. policy toward Iran might look like.

Trump's first term as president was marked by intense pressure on Tehran. The U.S. withdrew from the “Iran nuclear deal,” formally revoking its signature from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018. This agreement, signed in 2015 by Iran, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, and Germany, stipulated the lifting of international sanctions on Iran in exchange for restrictions on its nuclear program.

Trump reinstated U.S. sanctions, thereby jeopardizing Iran's burgeoning cooperation with the European Union and several other countries that feared facing U.S. restrictions. Furthermore, Trump pushed for the normalization of relations between Israel and Arab countries, particularly the Gulf monarchies, partly as a counterbalance to Iran. In 2020, Israel signed the Abraham Accords with the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan. Saudi Arabia was next in line for normalization, a goal that remains on the agenda.

How Trump will act now is uncertain. Media reports frequently suggest that he might allow Israel to strike Iran’s nuclear facilities, or that the U.S. might carry out such an attack alongside the Jewish state. However, it is also possible that Trump could unexpectedly decide to negotiate with Tehran in order to again limit its nuclear program.

Much will depend on the international and regional landscape, as well as the situation inside Iran, where a change in leadership is inevitable in the near future. This year, Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei will turn 86. Moreover, the question of the resilience of the clerical regime as a whole remains acute — Iran constantly faces the threat of social upheaval due to economic troubles or other issues. The 2022 protests over hijabs are still fresh in everyone’s memory.

The protests in Iran in the autumn of 2022 began after the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who was detained by the police for violating hijab-wearing rules

Iran is currently experiencing a severe energy crisis. At the end of 2024, this led to a series of rolling power outages in several regions of the country, resulting in the temporary shutdown of government and educational institutions, as well as many industries. All of this is affecting the mood of Iranians, who are dissatisfied with the fact that the authorities invested billions in Syria and built a network of proxies across the Middle East — in Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen — while neglecting domestic issues.

Partnership and competition

Russia and Iran actively supported Bashar al-Assad, especially after the onset of the Syrian civil war in 2011. However, it cannot be said that they were allies — rather, they were rivals who knew how to reach agreements. This applied to economic, political, and military matters. Russia was far from pleased with the excessive presence of pro-Iranian forces in Syrian territory, as well as the fact that Iran was putting Syria at risk of Israeli strikes. There were times when Russia acted as a mediator between Iran and Israel, urging the Iranians to pull back their proxies from the Israeli border and place them deeper inside Syrian territory. At the same time, voices in Iran constantly accused Russia of not using its air defense systems in Syria and allowing Israel to strike pro-Iranian targets.

A particularly telling episode was the attempt by Moscow and Tehran to shift the blame for the fall of Assad’s regime onto each other. A recording of a speech by General Behruz Esbatifrom the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) surfaced in the media. According to him, Iran had requested 1,000 Kalashnikov rifles from Russia in order to secure a critical front line against anti-Assad forces, but the request was denied. Russia also refused entry to an Iranian plane carrying weapons to Syria, he said. Esbati further criticized Russia's airstrike strategy in Syria, claiming that instead of targeting key concentrations of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham militants and weakening the proxy forces supported by Turkey and Qatar, Russian air assets were striking residential areas or desert land.

A particularly telling episode was the attempt by Moscow and Tehran to shift the blame for the fall of Assad’s regime onto each other

In turn, commenting on the Nov. 30 fall of Aleppo — the first major city captured by anti-Assad forces — Putin openly stated that 30,000 Syrian government troops along with the “so-called pro-Iranian units withdrew without a fight” — even though there were purportedly only 350 militants on the other side. He emphasized that Russia did not have ground troops in Syria. “We even withdrew from there in due time as part of a special operation. We simply didn't fight there,” Putin said.

Commenting on this situation, particularly Esbati’s words, a source in the Iranian government told the Qatari publication The Middle East Eye that, “The Russians have their claims against us. they say we performed poorly on the ground. But we, in turn, have our claims against them.”

It is also worth recalling another scandal between Moscow and Tehran. In 2021, then-Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif stated that Moscow had attempted to undermine the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) at the signing stage, as any rapprochement between Iran and the U.S. ran counter to Russian interests. His words were made at a closed event and were not intended for the public, but they still leaked to the media.

Against this backdrop, a story that came out in The Times in early January is quite sensational, revealing that Ali Larijani, a senior advisor to Iran’s Supreme Leader, secretly visited Moscow several times to request Russian assistance in developing Iran’s nuclear program and air defense capabilities.

It is highly doubtful that Russia is interested in advancing Iran’s nuclear program, which would result in the emergence of another nuclear power on its borders. But civilian nuclear energy is a different matter.

Competition in the oil market also should not be overlooked. Following the reimposition of U.S. sanctions, Iran has become almost entirely reliant on China as its primary oil market. China’s share of Iranian oil exports surged from 37.2% in 2018 to 90% in 2024. However, this growth has been severely undermined by the flood of Russian oil being redirected to the non-Western world. After 2022, Moscow shifted its focus eastward — primarily toward China — displacing not only Iran but also Saudi Arabia from the market.

Iran is significantly undermined by Russia’s price dumping on the oil market

It is also important not to forget about China, which competes with Russia in the Middle East. Until recently, Beijing was primarily focused on economic expansion in various regions, but now it has become actively involved in politics. In 2023, it was in China that the agreement on normalizing relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia was signed. In 2024, Beijing also became the venue for inter-Palestinian meetings, mirroring Russia's approach to diplomacy. At the moment, Moscow and Beijing’s political goals in the Middle East are largely aligned. Both capitals position themselves in opposition to Washington, though different dynamics may emerge with Trump. Where Iran will stand in this new reality is unclear.

It is also crucial to remember that Iran’s views on regional issues differ significantly from those of Russia. Beyond the ongoing disagreements over Syria, there is the issue of the Caucasus. Iran is closely connected to Armenia, a country with which Russia has a complicated relationship. Meanwhile, Iran faces numerous challenges regarding Azerbaijan, and there remain long-standing debates with multiple states over the division of the Caspian Sea’s waters. In short, mistrust exists among the region’s players, even if they are currently in agreement that the U.S. represents an adversary to them all.

Iran’s grievances and suspicions toward Russia are not new. They date back to the era of the Russian Empire, when the two countries fought each other, and things did not improve after World War II, when Moscow and its Western allies divided up the world.

For Iranians, however, there is no distinction between the past and the present. Few Russians today recall the details of the Russo-Persian War of the 19th century (apart from the killing of Alexander Griboedov). Iranians, on the other hand, still harbor resentment over territorial concessions they had to make as a result of that conflict. Tehran is highly sensitive to anything it perceives as an infringement on its sovereignty or territorial integrity.

Tehran is highly sensitive to anything it perceives as an infringement on its sovereignty

Russia, in turn, is genuinely concerned about the potential rapprochement between Iran and the West. In 2021, this was not as relevant as it is today. Meanwhile, Tehran remembers that during the reset of relations between Russia and the West under Dmitry Medvedev (2008-2012), the Kremlin allowed the approval of UN Security Council sanctions against Iran, which included the freezing of the S-300 missile defense system deliveries. It is believed that, in return, Moscow received strategic concessions from Washington, including the cessation of the development of the third missile defense area in Eastern Europe, the signing of the New START Treaty, and an agreement for Russia’s accession to the World Trade Organization.

A key feature of the relationship between Iran and Russia is that Tehran has never recognized the annexation of Crimea, nor the later annexation of other Ukrainian territories. The new agreement does not signal a shift in this regard. The fact is that Iran also has territorial disputes. The UAE — a close ally and strategic partner of Russia — claims three islands in the Persian Gulf that Iran has controlled since 1971.

Tehran has never recognized Russia's annexation of Crimea

Iran has also refused to acknowledge that its drones were used by Russia in military operations in Ukraine, a stance that resulted in a break in diplomatic relations with Kyiv — along with the imposition of new Western sanctions. Despite its material support for Russia, Tehran continues to advocate for a peaceful solution between Moscow and Kyiv. This was reiterated by President Pezeshkian at a press conference following the signing of the agreement, and the domestic press appears to concur.

“At present, Tehran is paying a high price for its alignment with Moscow, and the benefits of this strategy remain unclear. Iran has become a clear adversary of Ukraine, a country that, leveraging its international support, is exerting pressure on Iran. Kyiv has stepped up its lobbying efforts to rally allies against Tehran,” an article published in the English-language Tehran Times states.

It is also noted that, despite deepening its relations with Russia, Iran is not reaping equal benefits. Due to the international isolation that both states face, their cooperation is driven more by necessity than by mutual advantage. Given that Moscow and Tehran are uncertain about how the other’s relationships with external players — whether Arab countries, the European Union, or the United States — will develop, or how global and Middle Eastern events will evolve, they have preemptively agreed, if not to actively support one another in conflict, at least not to act against each other. In essence, this is perhaps the primary purpose of the agreement signed in Moscow.