Hundreds of journalists who left Russia after the war are facing an identity crisis. Many have not yet decided whether it is emigration, temporary relocation, or humanitarian evacuation. This is not the first time that Russian journalists have found themselves in this situation. The experience of Russian publicists, who in the second half of the nineteenth century were forced to write from Europe because of censorship restrictions, may be particularly relevant for today's emigrants.

Emigrants for emigrants

There were quite a few waves of emigration in Russian history, so one must choose comparisons carefully. One cannot, for example, say that for journalists who left the country the current situation is anything like the situation of the White emigrant newspapers and magazines for which the young Vladimir Nabokov wrote.

Frankly, there is virtually nothing in common in either the domestic situation or the mode of work. The White emigration consisted of a huge number of people who had left Russia, completely severed their ties with the country and were left to boil in their own juices. Besides they had almost no contact with people inside the USSR, and their publications (which often came out in a sizable number of copies - in Berlin, for example!) were done hermetically, that is, by emigrants for emigrants.

It cannot be excluded, of course, that at some point in 2022 or 2023 such kind of publications (emigrants for emigrants) will also surface in the new emigration centers - primarily in the Transcaucasia and the Baltic countries. But it is important to emphasize that they did not appear during the first 100 days of the war, while new names and brands (usually small and compact media outlets) did emerge in addition to the well-known relocated media outlets.

Why is that? Virtually all of today's émigré publications in Russian work remotely. In Putin's Russia, they work according to the principle of “body here, soul there.” Thanks to instant messengers and social media, which somehow continue to operate despite being blocked in Russia, this sentiment has intensified. For some, almost nothing has changed since the pandemic.

All contemporary émigré publications in Russian work remotely according to the «body here, soul there» principle

Therefore, the most accurate analogy would probably be the journalism of the Russian diaspora in the second half of the 19th century. It, too, can be described by the «body here, soul there» formula (at least in part). Let's look at that journalism in order to understand its causes and preconditions, find similarities and differences between then and now, and draw some conclusions.

Atmosphere of hope and enthusiasm

Let's start with the fact that there was no migration of free and independent media outlets from tsarist Russia. Free and independent media - in a very limited form - existed only for a short time after 1905. At that time all publications of all stripes inside Russia always (!) worked in the conditions of censorship. The same is true of our classical literature, which we study at school.

We don't know and will never know what that literature might have been like without censorship, but the press archives have survived - and yes, the differences are quite strong. While Dobrolyubov had to use Aesopian language to “admire” police measures, trials, and repression, if you printed a newspaper in London in a free printing house, you could call things by their proper names. Translated into today's realities, you could call “war” “war,” for example.

But let us return to the emergence of the phenomenon itself. The Russian émigré press of the 19th century arose under dramatically different circumstances from those of today, in an atmosphere of hope and general enthusiasm.

The final years of Nicholas I's reign are indeed very similar to Putin's current regime - they are also referred to as the “gloomy seven years.” It was a period of stifling any sign of freedom inside the country, of tightening the screws, of doling out conspicuously cruel punishments for nothing (Dostoyevsky's fake execution for a copy of Belinsky's letter is one example). That was the period when Russia entered the Crimean War, where instead of weak Turkey it found itself in conflict with almost all of Europe.

At the same time, Alexander Herzen, godfather of Russian journalism in exile, left the country. It was the time of revolutions in European countries, and Herzen actively joined, as we would say today, “the movement.” For this, the tsar, in a move that specifically targeted Herzen, froze his considerable fortune in Russia. Sounds familiar, doesn't it? With the help of the banker Rothschild, however, the revolutionary managed to, let's put it this way, unfreeze his accounts.

Alexander Herzen

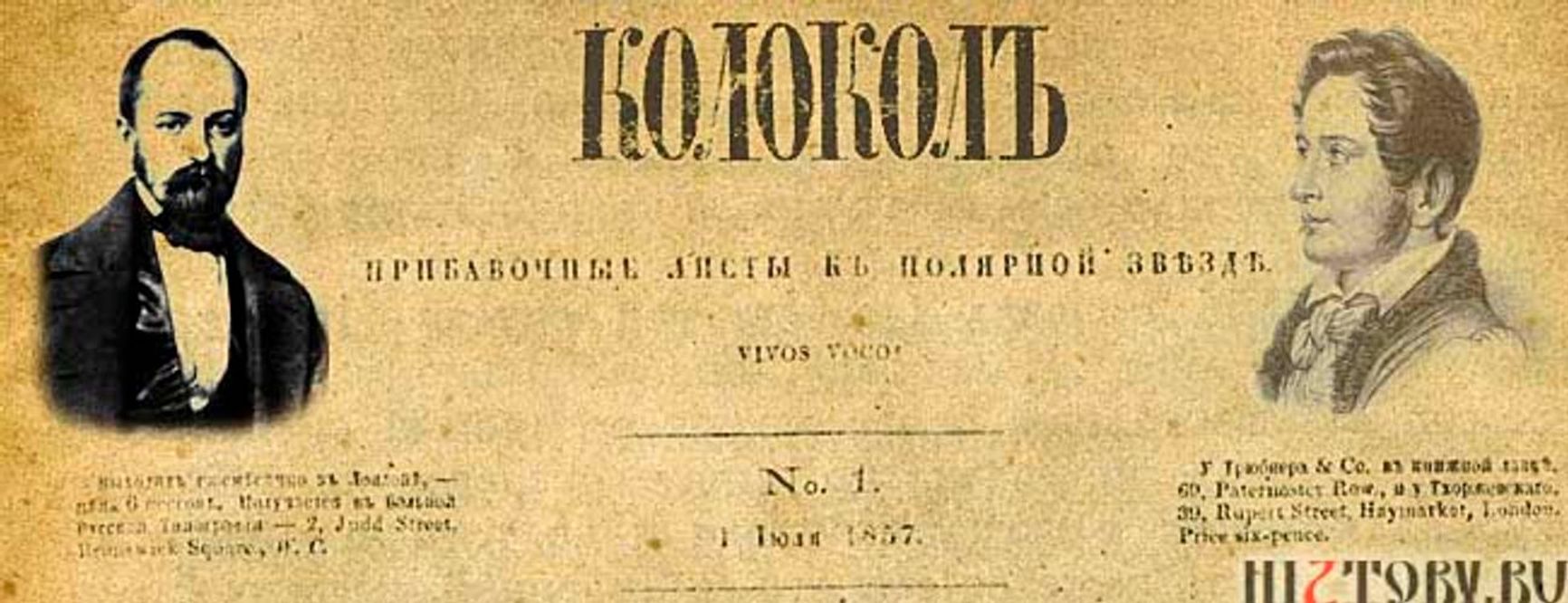

One way or another, he had money. But the newspaper Kolokol, the flagship of the future émigré press, did not come out until July 1857. Two years after the death of the tyrant tsar and a year after Russia's defeat in the Crimean War.

What was that time like? Paraphrasing Talleyrand, Leo Tolstoy recalled it this way: “Whoever did not live in 1856 does not know what life is.” Russia awoke from its slumber, as Pushkin had promised, and everything started to pulse and got into motion. Society was waiting for change, and it seemed more and more real.

“If we just sit idly and content ourselves with fruitless grumbling and noble indignation (...) then Russia will not see any bright days for a long time to come,” Herzen wrote at the time. It is with this mindset that he created Kolokol as a lobbying tool, which would enable him to put pressure on the new tsar's government and prevent it from dodging real reforms.

If we're content with noble indignation, then Russia won't see any bright days for a long time to come

Kolokol, which was sent illegally, but in a huge number of copies, to Russia, was published not only and not so much for those who could have called themselves an opposition. Top government officials in charge of peasant and other reforms also read it in their offices. It was, in fact, a dialogue, albeit not a direct one. Moreover, more and more anonymous material from Russia was reaching Kolokol - in essence, it was a platform for uncensored ideas, a discussion club for a country on the threshold of reform.

Looking at Herzen, his comrades, and their paper through this lens, it becomes increasingly clear that it was not about them or about inventing some exceptional product. In surfer terminology, they were simply riding a mighty wave that was rising on its own - for some time. After the emancipation of the peasants and especially after the Polish uprising of 1863, Kolokol lost its relevance dramatically. Public opinion in Russia was not ready for the Polonophile rhetoric. Herzen published the newspaper in French for a while before closing it altogether.

The First Issue of Kolokol

Substitute for a parliament

The well-known Russian-Soviet literary critic Svyatopolk-Mirsky (the son of the tsar's minister of the interior), in his fundamental history of Russian literature originally written for English students, makes a very precise observation: the Russian journals of the 19th century and their literary critics like Belinsky, Dobrolyubov, Pisarev and others should be viewed rather as a political phenomenon, as a substitute for a parliament, a future Duma, in its absence. Simply put, when Dobrolyubov wrote about Ostrovsky's “The Tempest”, he was writing not so much about the play itself as about his political views.

Belinsky, Dobrolyubov, Pisarev should be viewed as a substitute for a parliament

The same idea applies, and to an even greater extent, to newspapers and magazines published abroad. Kolokol was the first, and, as mentioned above, it peaked in popularity when there was a general demand in the our-hearts-yearn-for-change vein, and then the publishers could not make up their minds as to whether to steer toward the axe or toward a relatively peaceful transformation.

At the same time, in the 1860s and 1870s, other publications emerged that operated in essentially the same manner as Herzen did. They simultaneously became the voice of certain political groups within Russia, their mouthpiece and lobbying tool that allowed for a slight correction of public opinion and, with luck, the course of the government.

Not all of them were left-wing or center-left, like Kolokol. In fact, and here again we return to the Svyatopolk-Mirsky analogy, the entire political spectrum of the future State Duma was represented there - from moderate liberals like Golovin's “Strela” and Blummer's “Vesti” to constitutional monarchists like Prince Dolgorukov's “Budushchnost”, who also shockingly refused to return to Russia, but held very different views from Herzen's. Here is a typical quote from his newspaper: “We like neither revolutions nor revolutionaries.”

There were almost no ultra-conservative newspapers among the emigration, because it was not difficult to publish them inside Russia.

The Road to Revolution

The balance between the possible and the impossible in Russian journalism was constantly shifting. There were counter-reforms during the period of reforms, and after the assassination of Alexander II the country was in for a freeze.

But one way or another, the diverse political spectrum of émigré journalism described above was shrinking, consistently and steadily. In the 1880s and 1890s, it was already possible to publish liberal and, even more so, constitutional-monarchist newspapers and magazines in Russia, albeit with certain reservations.

In the 1880s and 1890s, it was also possible to publish liberal newspapers and magazines in Russia

The émigré press was becoming almost exclusively leftist - anarchist, Marxist, revolutionary (Stepniak-Kravchinsky, Volkhovsky, Chertkov, the notorious Plekhanov and others). This was no longer just the press; it was the (future) party press, unequivocally calling for barricades, for revolution and civil war.

All of that, as you know, came true. Not everyone liked the result, including myself. So, you have to be careful about what you call for, even by means of an insignificant émigré leaflet. After all, your wishes may come true.