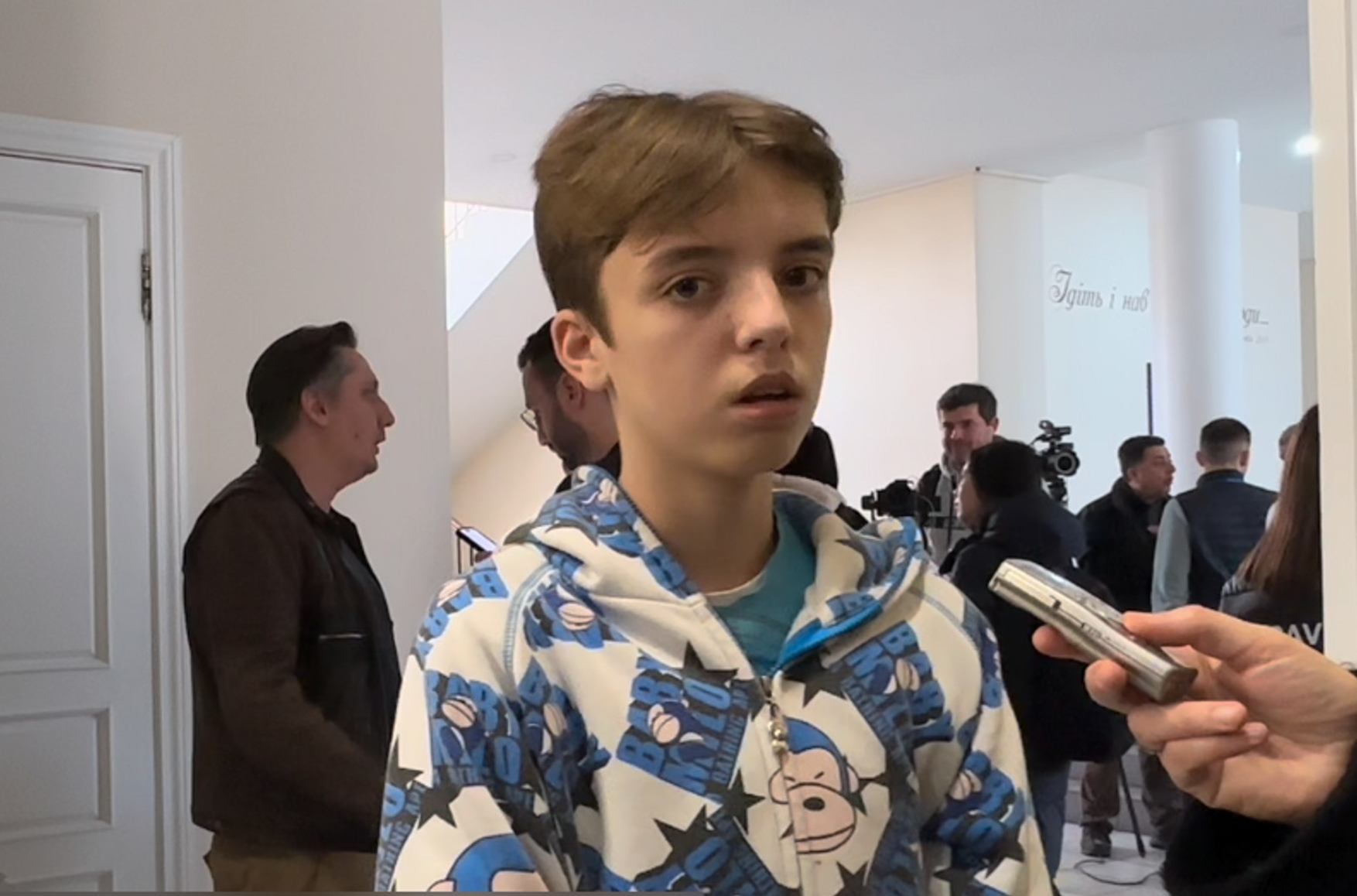

Last October, the Kherson region's occupation authorities sent a group of seventeen children to children's camps located in annexed Crimea. However, after spending six months there instead of the promised ten days, the children have returned to Ukraine. Tatyana Popova, a correspondent for The Insider, spoke with the returning children and their parents in Kyiv. One of the children, sixteen-year-old Vitaly, reported that at Camp Mechta [Dream] in Yevpatoria, those who supported Ukraine were physically assaulted with an iron stick:

“Astakhov, who is in charge of security, was the one who wielded the iron stick. He acted as if he was the tsar there. He told us, 'You're from Ukraine, who needs you? We'll take you to a boarding school, you'll spend time there, and you'll understand everything.'” One girl was hit on the back with the iron stick, resulting in a visible striped bruise.

We were just chilling in the hall when suddenly someone shouted, “Glory to Ukraine!” and another person answered, “Glory to the heroes!” The security personnel took them away, and I have no idea what happened to them afterwards. The man responsible for security also burned the small Ukrainian flag on a stick that one of the girls had received from her parents who had brought it from Kyiv. She had put the little flag in a cup and then hung it on the curtains, but the security chief came in, ripped it off, and started yelling, “You Ukrainians are sick! You are in Russia now, there will never be a Ukraine here, it will just burn down. Come with me, you're going to watch Ukraine burn.” He lit the flag on fire with a lighter, and it just burned down.”

A man with the last name Astakhov from Yevpatoria is in the “Myrotvorets” database, but The Insider was unable to reach him.

Vitaly said that he and his girlfriend ran away from camp for two days:

“We just said “Glory to Ukraine!” and ran away and hid for two days. We found a hotel in Yevpatoria, and the girl managed to get a wire transfer of 600 rubles from her mother, and we rented a single room and slept on the floor. We bought our own food and managed to survive. There was an eternal flame in the city center with a Russian flag hanging nearby. My friend went over and put it out with her foot. There was an old lady standing nearby who supported Ukraine, and she said, “I've been waiting for Ukraine for eight years.“”

The police eventually located the children and took them back to the camp, where they were threatened and intimidated with false claims that their parents had abandoned them. The children were told that they would never be allowed to return to Ukraine and would be placed with foster families instead.

“They told us that Ukraine will burn and we'll never be able to go back home without problems. They even threatened to send us to a boarding school in Pskov, but we stood our ground and told them: “Our parents didn't abandon us, and you don't get to take us anywhere.” The staff continued to insist we had been abandoned. My mother called the camp director and said: “What are you talking about? I didn't mean anything like that! Why are you lying to the kids?” They told her, “You're not taking them back anyway. They will be Russia's children.”

According to Vitaly, after being at Camp Mechta, all the children were transferred to Camp Druzhba [Friendship], where the conditions were even worse. They were given dirty mattresses and pillows instead of proper bedding, and as a form of punishment for disobedience, they were locked in the basement for several hours:

“They made us sing the Russian anthem, hold the Russian flag, raise it on the flagpole, but we didn't do that. They sent us the text of the anthem and said: “Learn it, tomorrow you will be reciting it.” But then they forgot about it for some reason. We were kept in the basement. They said: “You are Ukrainian patriots, and we don't need you!” They kept one girl there for four hours. Everyone was treated in a different way. They made us clean the corridors because the cleaners did not do their job. There were no bedclothes, only a pillow and a dirty mattress. Not in the basement, in the rooms. We bought a light bulb ourselves and screwed it in so there was at least some light. There were no power sockets in the room either. I complained [about the bad conditions], and they told me: “You're from Ukraine, sleep on whatever you have.”

Initially, the authorities would not allow the children to leave the camp, citing security reasons, and then they simply refused to allow them to return home. Eventually, arrangements were made for the children to be returned to Ukraine, but Russia demanded that their parents pick them up in person. “They were told: “If you want, come and get your children if you need them.” But in fact, after the corresponding areas had been de-occupied, the front line separated the mothers from the children, and the mothers were unable to come and get them,” Miroslava Kharchenko, coordinator of Save Ukraine, told Real Time last December.

“The cover story was that they were going to the camp for two weeks. First they went for two weeks, then the kid called me and said they were extending it. On November 4 they were supposed to get back, but the Crimean bridge was bombed,» the mother of one of the girls told The Insider. “Our troops retook Kherson in November, and we asked about picking up our child. We had to leave Kherson with volunteers from the Khmelnytskyi region, and there a childcare inspector gave us volunteer Katya's phone number via the police. We drove through the Russian Federation. On Sunday I was driving to Kyiv, and on Monday night we had already left for Poland, then Belarus, Russia, and Crimea, and then back.”

«We waited for 6.5 months since we left. We applied to Save Ukraine, filed an application, my spouse called and said we had to wait because there were so many children, but the problem was slowly being resolved. A volunteer called a week ago and said there was a man who could take the kids. We wrote a power of attorney for a woman who was on her way to Yevpatoria to pick up her child. They came, picked up the kids and brought them back within two days. Yesterday we came from Kherson, they met us, put us up in a hotel, and in the morning we came to pick up the children. We lived in Kherson the whole time», says the father of another child.

Not all children encountered abuse in the camps, but all speak of poor conditions and substandard food.

“First I was in the first camp, the Druzhba. The conditions there were very bad - six power sockets per floor, with 50 people living on each floor. Two bathrooms and two toilets for boys and two for girls,” Vlad from Kherson says. “They seldom cleaned the place. The food is worse than average, as it were.”

According to Vlad, there were lessons according to the Russian curriculum in the camp. They made the kids stand up when listening to the Russian anthem during morning exercises. Then the kids were moved to the Luchisty [Radiant] camp. “Everything was much better there – great rooms, a bathroom in each room, a minimum of five power sockets per room, and much better food. There were some clubs, soccer, volleyball, and so on,” the boy says.

According to a report from Yale University, over 40 camps for Ukrainian children are currently active in various regions such as Siberia, the Black Sea coast, the Urals, and annexed Crimea. The report claimed that these camps promote “traditional values,” teach history based on “Russian standards,” and make children practice shooting and handling weapons. Certain camps, including those in Chechnya and Crimea, are even alleged to offer a “young fighter course” for kids.

In late December, it was reported that the management of children's camps in Crimea had been preventing Kherson children from returning home. Additionally, over 100 children from another camp did not return to Balakleya.

The state portal Children of War's website says that 16,226 children are missing. According to the website, so far 308 have been returned to their homeland.

The International Criminal Court in The Hague issued arrest warrants on March 17 for Russian President Vladimir Putin and children's ombudsman Maria Lvova-Belova, alleging their involvement in the forced removal of children from Ukraine.