A year ago, Russia's Supreme Court declared the “International LGBT movement” an “extremist organization.” Although such an organization does not exist and never has, the ruling effectively puts all LGBT people in Russia at risk of persecution, along with activists defending their rights. The development is not entirely without precedent in Russia's history. For over half a century — from 1934 to 1993 — “sodomy” was treated as a criminal offense. But despite the constant fear of imprisonment, Soviet gay activists continued their fight for equality. They organized educational campaigns, published newsletters, and worked tirelessly to abolish Article 121 of the Criminal Code.

Content

Meanwhile in the USSR

Street resistance of the 1970s

Western assistance

Hidden activism of Soviet lawyers

Soviet gays' early attempts at self-organization

Gay activism during perestroika: Moscow and Leningrad

Gay conference in Leningrad and Moscow

Assistance to Yeltsin

Abolition of the article and the end of the active phase of gay resistance

The struggle for queer people's rights gained momentum in the West in the second half of the 20th century. In the United States, the so-called Stonewall Riots of 1969 are widely regarded as the pivotal moment. In response to yet another police raid on the New York gay bar “Stonewall,” gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and other marginalized groups stood up to the police, with the clashes continuing for several days.

In the wake of these events, LGBT activists in the U.S. and abroad began to organize more effectively, advocating for the legalization of same-sex relations and fighting against discrimination. The self-organization of the American gay community following the Stonewall Riots led to significant victories. For example, in 1973, under pressure from activists, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders.

In Europe, with the support of progressive doctors and lawyers, queer people successfully pushed for the repeal of discriminatory laws. As a result, male homosexual relationships were legalized in England and Wales (1967), East Germany (1968), Bulgaria (1968), West Germany (1969), Austria (1971), and Norway (1972), among other countries.

Meanwhile in the USSR

Soviet queer people also faced considerable hardship. Homosexual relations between adult males were criminalized, with approximately 1,000 people per year being convicted under this charge across the USSR in the 1970s and 1980s. While there was no criminal punishment for female homosexuality, such women were often subjected to “treatment.” Many men and women, realizing their “unnatural attraction,” attempted to suppress their desires by dating and marrying people of the opposite sex.

Only a few, typically those living in larger cities, could afford to lead an active homosexual lifestyle. The term “gay” was not in use. The police referred to such people as “pederasts,” doctors as “homosexualists,” and gays and lesbians themselves primarily used euphemisms such as “being in the know” or “one of us.”

The Stonewall Riots had no notable influence on the development of gay activism in the USSR. This was due in part to the impenetrability of the Iron Curtain, but also to the significant differences in the political structure of Soviet society. Entirely different events were unfolding in the USSR at the time. In 1968, the Warsaw Pact countries sent tanks into Czechoslovakia to suppress the Prague Spring — a movement aimed at liberalizing the country. While these events did spur increased dissident activity within the USSR, no Soviet dissidents fought specifically for the rights of Soviet homosexuals or advocated for queer issues.

Street resistance of the 1970s

Although there was no clear “Western-style” gay activism in the USSR, homosexual social life did exist. Those Soviet queer people who were not afraid to meet others like them did so at the so-called pleshkas (small squares) — designated places for socializing, meeting, and making acquaintances. Of course, homosexuals living in Moscow or Leningrad, unlike those in smaller cities, found greater acceptance of their lifestyle. Many of them understood well that they were victims of homophobic pressure from the state, and they sometimes even attempted to push back against it.

One regular of a Moscow pleshka, a young man nicknamed “Mama Vlada,” vented his anger at the Soviet homophobic regime in an interview with Vladimir Kozlovsky, a lexicographer from New York who came to the USSR in the 1970s specifically to study the lives of Soviet homosexuals:

“And what's the problem with us? The problem is we’re nonconformists, not like that frigging proletariat whose legs are practically sunk into their asses from drinking! We're unreliable, we’re hard to control. What a barbaric country. And we’re the ones who suffer the most because of it. Look, in Sweden or the Netherlands, they say men can get married, but here, sometimes guys are afraid to walk down Gorky Street arm in arm. Our leaders, those frigging idiots, don’t get it — no matter how much you lock me up or try to 'fix' me, I’m not changing. It’s just not up to me. I was born this way. For me, everything you call normal sex is unnatural and disgusting. Oh, if only the people in charge knew what amazing names we have in our ranks... Their own KGB officers, a police commissioner, some people in the government, and state-approved artists, honored cultural figures...”

“Mama Vlada” also told Kozlovsky about the resistance some homosexuals put up against KGB officers, who were often sent to their meeting spots to catch them in the act. For example, one agent sent to Yekaterininsky Garden on Ostrovsky Square in Leningrad, across from the Alexandrinsky Theater — a spot known among Leningrad’s queers as “Katkin Sad” — encountered a young homosexual who unexpectedly fought back:

“They say one such agent ran into our karate guy. He flashed his ID, but the guy didn’t back down. He screamed and hit him so hard that the small tibia bone went into the large one and out through his ass! And he also took twenty rubles from his party wallet — for the trouble and as a warning. Next time he won’t stick his nose in, if he gets out of the hospital.”

But such cases of queer street resistance were certainly exceptions.

Western assistance

As a result of the thriving queer activism in the West, the situation of Soviet homosexuals began to attract the attention of foreign queers. Foreign gay activists, who were actively fighting for their rights at home, expressed sympathy for Soviet gays and tried to contribute in their own way to the fight against Soviet homophobia. Some of them, pretending to be fans of communism, would obtain a visa to the USSR, travel to the country, meet with homosexuals in major cities, interview them, and sometimes even participate in public demonstrations.

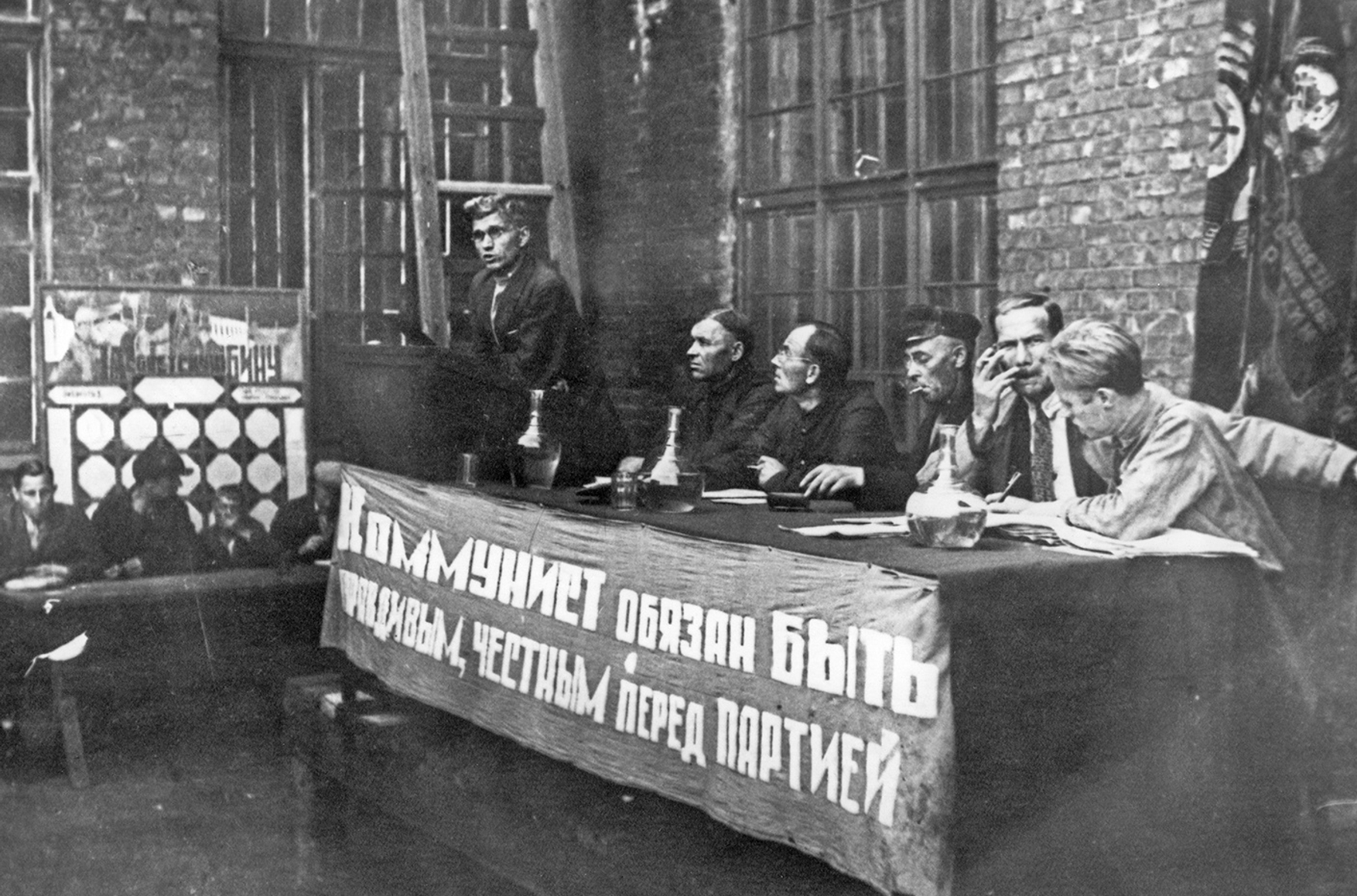

In 1977, Angelo Pezzana, an Italian and a founder of Fuori! — one of Italy's first pro-gay organizations — came to Moscow with a secret mission: to organize a public demonstration in support of Soviet gays. A few days before the planned action on Red Square, Pezzana met with Andrei Sakharov, the renowned Soviet dissident, to ask for his backing. Sakharov declined:

“I cannot support you publicly. They’ll say I’m a homosexual, and I have to fight for the civil rights of everyone. But what you are doing is absolutely right.”

Dan Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Dan Healey, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

Tema magazine, #1 (1990)

Ty magazine, 1992.

Angelo Pezzana

Pezzana did not give up: he was determined to carry out his plan no matter what. However, soon the KGB learned about his intentions. On the day of the demonstration, they detained the Italian at the entrance of the Metropol hotel. After snatching a poster from his hands that read “Freedom for Homosexuals in the USSR,” the KGB agents put him in a car.

At Lubyanka, they interrogated him. Through a translator, they asked him to provide a list of Moscow homosexuals whom he knew personally. Pezzana refused and said he didn’t know anyone in the city. The KGB officers then threatened him with deportation and a visa denial. To this, Pezzana replied: “I don't want to go back until true libertarian socialism is established here.”

After getting nothing from the Italian, the authorities put him on the first flight to Milan.

Hidden activism of Soviet lawyers

Among Soviet lawyers, there were those who could be called “hidden activists.” The first attempts to abolish the law criminalizing sodomy — introduced by Stalin in 1934 — were made by Soviet lawyers as early as 1959. At a discussion of a special legal commission's amendments to the new Criminal Code of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), prominent lawyer Boris Nikiforov proposed removing the first part of the article, which criminalized homosexual relations between two adult men.

Dan Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Dan Healey, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

Tema magazine, #1 (1990)

Ty magazine, 1992.

The first attempts to abolish the law against sodomy were made by Soviet lawyers as early as 1959

The next attempt to repeal the statute against consensual sexual relations between adult men came from lawyer Pavel Osipov of Leningrad University in the late 1960s. He openly criticized the criminal prosecution of “non-violent” — i.e. consensual — homosexual relations:

“What purpose can the legislator have in prosecuting non-violent homosexuality, when it concerns individuals with a biologically distorted sexual instinct? It is hard to believe that criminal law can correct this biological anomaly or compel these individuals to seek heterosexual satisfaction of their sexual needs.”

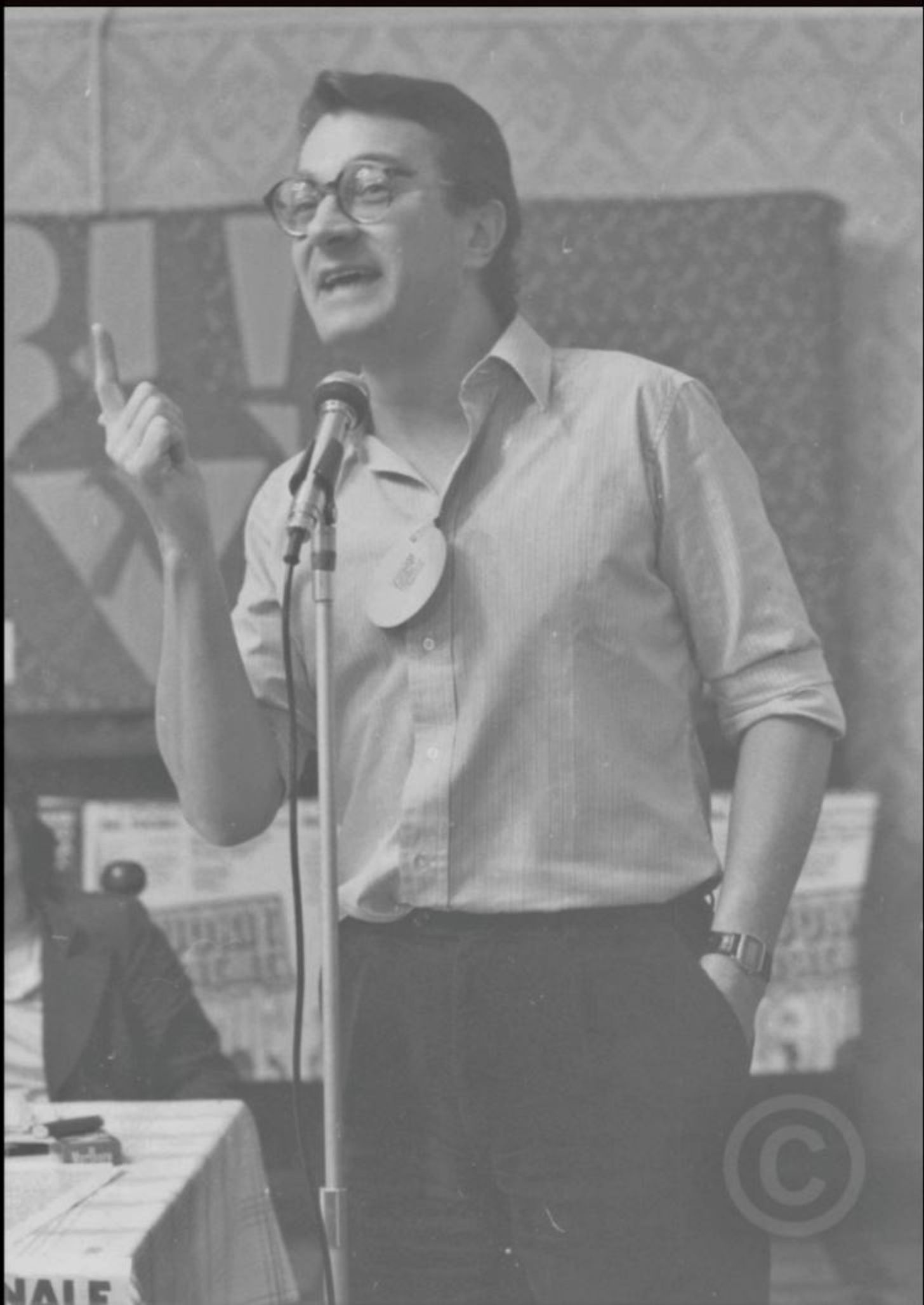

Another prominent Soviet lawyer, Alexei Ignatov, also actively advocated for the abolition of criminal punishment for “voluntary sodomy.” In his doctoral thesis, “Problems of Criminal Responsibility for Crimes in the Area of Sexual Relations,” he wrote:

“In extensive medical and legal literature, both domestic and foreign, it is convincingly argued that consensual homosexual relations between adults do not pose a public threat and do not harm the state.”

However, such bold statements did not gain support from party officials. In 1974, just weeks before Ignatov was scheduled to defend his dissertation at the All-Union Institute for the Study of the Causes of Crime and the Development of Crime Prevention Measures, a high-ranking party official called the law department to express dissatisfaction with the fact that Ignatov was allegedly promoting debauchery. Ignatov was informed of this.

Dan Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Dan Healey, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

Tema magazine, #1 (1990)

Ty magazine, 1992.

Alexei Ignatov

On May 6, 1974, Ignatov defended his dissertation. First, he presented his thesis to the committee, then they began to ask him questions. One asked Ignatov about the legal status of homosexuality in the USSR: “Based on the principles of criminal law, does homosexuality violate the basic norms of socialist morality?”

Ignatov had to treat cautiously. His career was at stake:

“It seems to me that the issue of responsibility for homosexuality, and, in general, the issue of sodomy, should be addressed comprehensively. It goes beyond a purely legal matter and requires deep and thorough investigation. Proposing to abandon responsibility for sodomy, apparently, is premature. Public consciousness and public opinion are not yet ready for such a decision. And in this regard, you are correct in stating that this act is indeed condemned by socialist morality and is considered a violation of the fundamental principles of socialist morality by our Criminal Code.”

The response from the panel was satisfactory. Yes, Ignatov had to retract his boldest proposals, but he did not abandon his covert activism. Several years later, in 1979, after his dissertation defense, he sent a letter to the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR. Once again he urged officials to address the need to abolish the criminal punishment for sodomy. The letter went unanswered.

Soviet gays' early attempts at self-organization

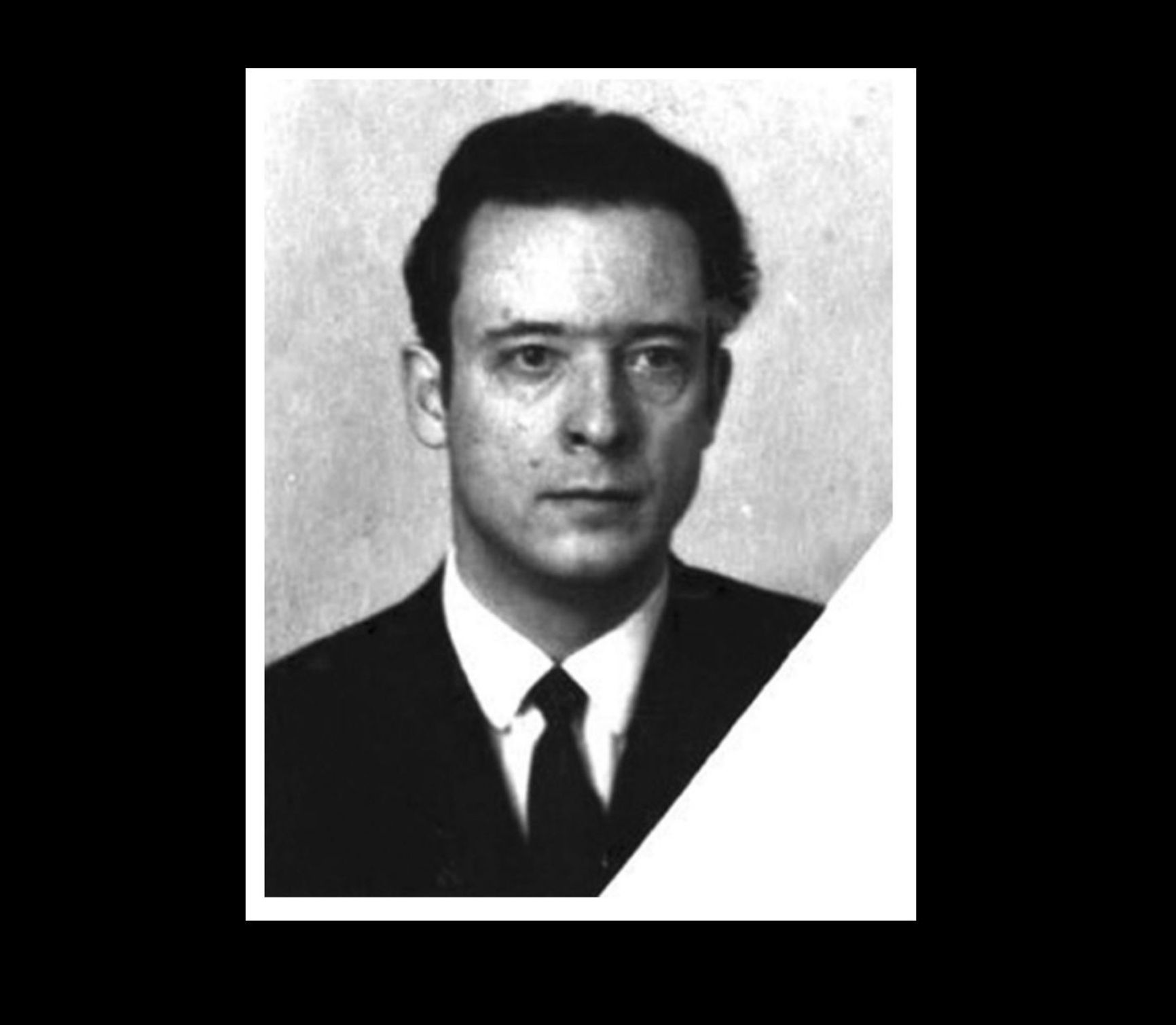

In 1984, a young philologist from Kyiv, Alexander Zaremba, moved to Leningrad, where he decided to organize an underground group to defend the rights of homosexuals. Seeking to gain from the experience of Western organizations, he reached out to the International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA), requesting that his group be accepted as activists.

Dan Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Dan Healey, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

Tema magazine, #1 (1990)

Ty magazine, 1992.

Alexander Zaremba

However, problems soon arose: membership in the organization required payment in foreign currency, as well as participation in annual regional conferences. Without foreign currency and an official visa, this was impossible. But Zaremba's group found a solution: they delegated all these responsibilities to the Finnish organization SETA.

By July 1984, Zaremba's group, now called the “Gay Laboratory,” had grown to 30 members. The group's main tasks were to raise queer awareness, study foreign languages, fight for the repeal of Article 121, and establish gay and lesbian clubs in the USSR. Zaremba was actively involved in organizational work and utilized the resources he had at his disposal: a large apartment in downtown Leningrad, knowledge of foreign languages, and extensive connections within the queer community — both inside the USSR and abroad.

When the HIV epidemic began, the Soviet Union remained silent about it. During this time, Zaremba's group worked diligently to spread information about AIDS among Soviet homosexuals, educating them on prevention methods and warning about the dangers of sexual contact with foreigners without using condoms.

Dan Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Dan Healey, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

Tema magazine, #1 (1990)

Ty magazine, 1992.

While the Soviet Union remained silent about the HIV epidemic, Zaremba's group worked diligently to spread information about AIDS among Soviet homosexuals

Some members of the group were involved in translating Western gay magazines and newspapers, while Zaremba himself collected information on “sodomy” prosecutions in the USSR and organized demonstrations at Soviet embassies abroad. However, it wasn't long before the KGB became aware of the group and forced it to cease its activities.

Gay activism during perestroika: Moscow and Leningrad

Meanwhile, serious social, economic, and political changes were afoot in the USSR. The country’s young General Secretary, Mikhail Gorbachev, was chosen in the spring of 1985. He came to power with the idea of pursuing “perestroika,” — rebuilding — and a process of liberalization commenced. Events moved rapidly. In 1989, elections for people's deputies were held in the USSR, and for the first time, Soviet voters could choose candidates for the highest governing body in the USSR. The First Congress of People's Deputies opened on May 25, 1989, and all of its sessions were broadcast live.

As the climate in the USSR became more liberalized, opportunities for queer activism grew. On October 9, 1990, Gorbachev signed the “Law on Public Associations,” which allowed the registration of non-communist political organizations in the country — before, the only existing organization in the USSR was the Communist Party, along with its branches, which included the Komsomol and trade unions. Just six days later, on October 15, 1990, an important event in the history of the Soviet gay movement took place in Moscow: the founding congress of the “Moscow Organization of Lesbians and Gays” (MOLG), led by activists Evgeniya Debryanskaya and Roman Kalinin.

Dan Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Dan Healey, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

Tema magazine, #1 (1990)

Ty magazine, 1992.

Roman Kalinin

The organization began publishing its own queer newspaper, Tema. In the first issue, it laid out a set of goals:

“We have taken as an example the fight for rights that homosexuals have been waging for many years in all civilized countries. We want to change society's attitude towards us, to make it more tolerant. The union's task is to fight discrimination based on sexual orientation. To end the criminal prosecution of homosexuals. To provide social rehabilitation for those suffering from AIDS. To combat the spread of AIDS through the promotion of safe sex. To educate the public on the subject of homosexuality. To break through the information blockade of homosexuality. To create spaces for meetings and connections. We want to convince people not to isolate themselves, not to feel inferior, but to live happy, fulfilling lives.”

At the same time, in other Soviet cities, there were also attempts to create and officially register local queer organizations. In 1990, twelve Leningraders decided to establish Nevskie Berega, a support group for Soviet queers. On September 10, 1990, meeting in a private apartment, the founders of the group adopted the organization's charter, then submitted all the necessary documents for official registration to the commission for public organizations of the Executive Committee of the Leningrad City Council. The goals of Nevskie Berega were similar to those of MOLG:

“The association is created to fight the alienation of homosexuals and lesbians from society, as well as to overcome their feelings of oppression and loneliness by providing necessary psychological support, preventing crisis situations, clarifying the public's unjustified fears towards homosexuals and lesbians, and assisting people in realizing their ideas of love and happiness.”

In October 1990, Professor Kukharsky, the leader of Nevskie Berega, visited the commission for public organizations at the Leningrad City Council. The founders of the new organization were met with open curiosity, but the reception was generally friendly. Kukharsky immediately informed the commission that the issue of personal sexual orientation had not been considered in the admission process for members, and he pointed out that among the organization’s founders were Soviet citizens who were legally married and had children.

The commission reviewed the organization’s charter, and only one point raised concerns: the one referring to the creation of an “independent urban infrastructure oriented towards homosexuals.”

“Does this mean your association plans to run a 'gay tram' through the city?” asked one commission member, posing a rather unusual question.

The issue was resolved when the founders of Nevskie Berega proposed changing the word “infrastructure” to “structure.” By the end of the discussion, the Leningrad City Council commission unanimously approved the organization’s composition and recommended its registration. However, the process was far from straightforward. Despite the commission's support, the Soviet Union still had Article 121, and homophobic officials actively sought to use it to block the establishment of political organizations for homosexuals.

Although the commission for public organizations had no objections to registering Nevskie Berega, the prosecutor of Leningrad was opposed. He argued that, “The content of the organization's charter contradicts the law, and their actions could be interpreted as promoting activities covered by Article 121 and other articles of the Criminal Code. The activities of this association would contribute to the spread of unhealthy interests.”

After the prosecutor's statements, on December 10, 1990, the Executive Committee of the Leningrad City Council denied the registration of the Nevskie Berega association.

In response, Nevskie Berega filed a lawsuit against the Executive Committee. The trial took place on February 20, 1991, and the court proceedings were recorded on video. Nevskie Berega executive director Kukharsky emphasized the organization’s focus on human rights and education — arguments which seemed to be understood by the judge.

However, when Kukharsky began discussing the organization's plans to open a gay restaurant and a gay nightclub, the judge could not conceal her disgust. After Kukharsky and other members of the association presented their arguments, the judge asked the question that ultimately became decisive: “Will there be members of the organization who engage in homosexuality?” Kukharsky replied honestly: “I cannot rule out such a possibility.”

Dan Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Dan Healey, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

Tema magazine, #1 (1990)

Ty magazine, 1992.

Upon hearing about the organization's plans to open a gay restaurant and a gay nightclub, the judge could not conceal her disgust

Nevskie Berega was denied registration. The court justified its decision by maintaining: “From the statements of the association's representative, it has been established that the organization’s activities will actively support individuals committing crimes under Article 121 of the RSFSR Criminal Code (by providing them with premises, as well as material and legal assistance).”

The city court upheld the district court's ruling. Nevertheless, despite the authorities' resistance, Leningrad's gay activists continued their efforts to establish new organizations, and a few months later, the Leningrad activists managed to register two local gay organizations: The Tchaikovsky Foundation and Wings.

Despite fierce opposition from bureaucrats, the movement to repeal Article 121 garnered strong support from Soviet rock musicians. In early 1991, they even released a special statement, which was later republished in the newly launched gay publications Tema and Risk:

“To our fans, their friends and opponents, and all reasonable people of the USSR,

The rock musicians of the USSR address you in the hope of being heard and understood correctly. We wish to openly express our views on the current Article 121, part 1, of the RSFSR Criminal Code, and regret that we did not have this opportunity earlier.

We are convinced that this article contradicts humanistic principles, the freedom of personal choice, and the right to choose for every civilized person on the planet. It deprives every reasonable, internally free, and mature (or on the threshold of maturity) person in our country of the right to sexual choice.

We believe it is essential, in the process of restoring the rule of law, to look to the experiences of developed and civilized countries. They have long recognized that so-called sexual minorities are a part of society as a whole. You must understand that people cannot change nature by relying on imperfect laws that they themselves have invented and which change at their whim. These laws will not strengthen morality or purify those deemed to carry 'filth'... A person is not above nature.

We call for reason and tolerance, especially now, as the country descends into chaos. These people must have their right to freedom restored, and their fear removed. It is shameful that such an article still exists in our state, which claims to prioritize human compassion to the world. Understand: the world is diverse, and that is its strength. Sexual inclinations are not uniform. Down with the discrimination of those who are different from you!'”

Gay conference in Leningrad and Moscow

From July 23 to August 3, 1991, an important event in the history of Soviet gay activism took place in Leningrad and Moscow: an international conference and film festival, attended by approximately 20,000 participants. One of them, Leonid, recalled: “For the first time in the history of our country, gays gathered together.”

Beyond film screenings, the festival included sessions addressing a wide range of topics: HIV and health, art and culture, politics and activism. The conference organizers remembered how the Soviet press reacted with remarkable interest:

“The Soviet press surpassed all our expectations. Once-pro-communist newspapers splashed front pages with photos of kissing men. The most popular Russian evening news program devoted a significant segment to a conference clip. Even the most conservative Russian newspapers covered the event, albeit in their own reactionary way.”

The conference ended with an unprecedented event — a gay demonstration in front of the Bolshoi Theatre. Standing on the iconic landmark’s cracked steps, Russian and foreign gays chanted:

“We are not afraid!”

“Fight AIDS!”

“Repeal Article 121!”

Many of the participants in the demonstration, including MOLG leader Roman Kalinin himself, had never taken part in such an action in Russian. Back in 1989, Kalinin had to use a pseudonym to avoid the police. Now, together with other Soviet gays, he stood in the heart of Moscow, chanting these slogans.

Assistance to Yeltsin

Meanwhile, the situation in the country was rapidly spiraling out of control. The discussion had long ceased to be about “perestroika,” and a clear trend toward independence for the Soviet republics, including the RSFSR, was emerging. Not everyone was happy about the changes: in August 1991, a group of high-ranking Soviet bureaucrats from the Soviet government and the KGB, dissatisfied with Gorbachev’s reforms and their consequences, decided to stage a coup. They formed a special government body, the GKChP. On August 19, KGB officials isolated Gorbachev at his dacha, and tanks were brought into Moscow.

Leaders of the gay movement, naturally aligned with the country’s pro-democratic forces, were seriously frightened. If the hardliners regained power, all the liberal achievements would be under threat — and gay activism would be impossible.

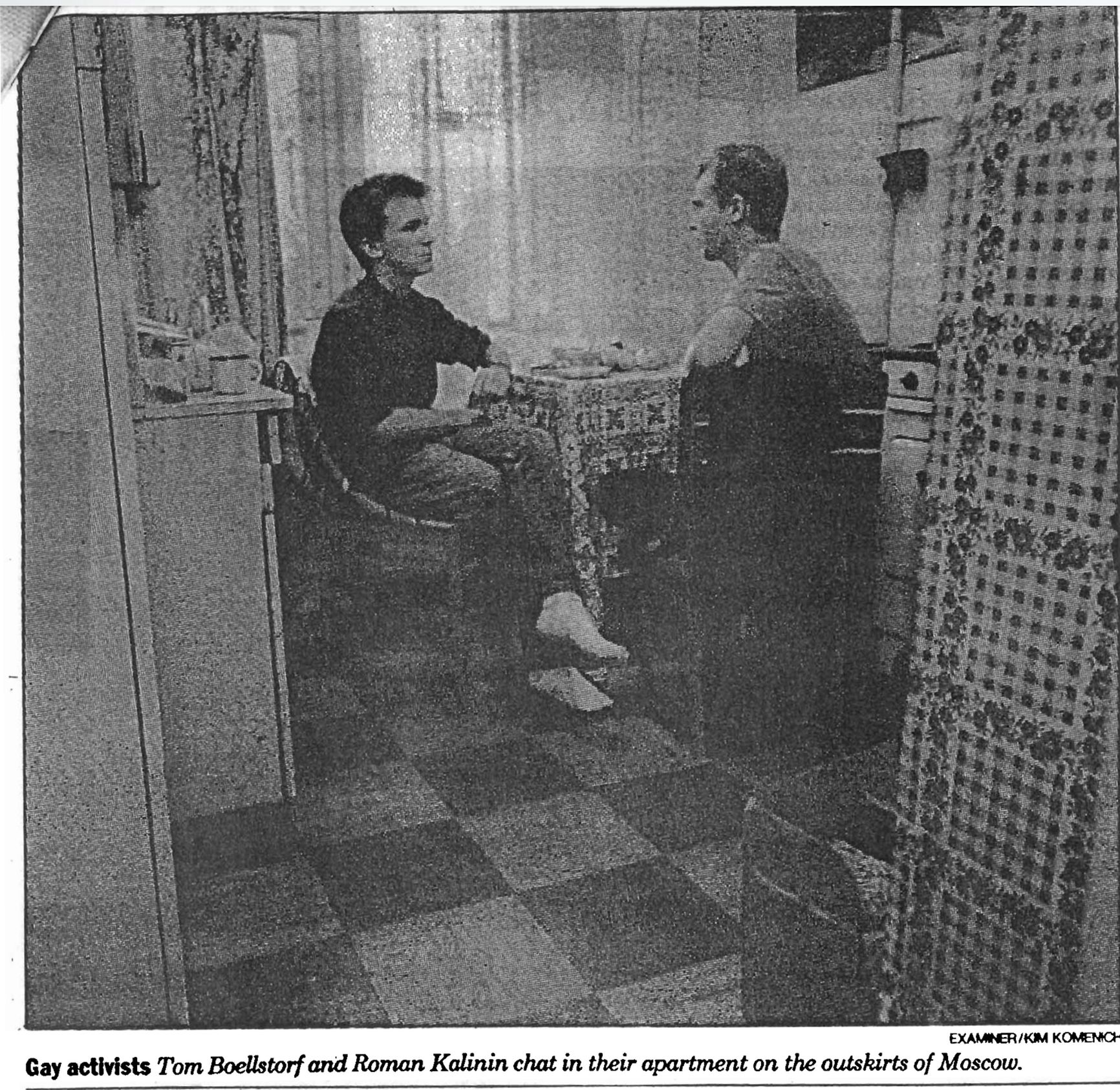

Kalinin was also deeply frightened. Realizing that the coup leaders would begin arresting public activists, he understood he would be among the first to be rounded up. That same day, he moved in with Thomas Boelstorff, his ally and a gay activist from the U.S. who had helped him with the creation of MOLG and the development of the Tema newspaper.

Despite the confusion in the first hours, by 4 p.m. leaflets with announcements from Yeltsin and other leaders of the democratic movement urging resistance to the coup began to appear at subway stations.

When the coup leaders announced the ban on all newspapers except the official communist ones, Kalinin and Boelstorff grew even more anxious — now their newspaper, Tema, was officially illegal. The next day, August 20, Kalinin and Boelstorff went to Manezhnaya Square near the Kremlin. But it was surrounded by tanks, trucks, and soldiers.

Dan Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Dan Healey, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

Tema magazine, #1 (1990)

Ty magazine, 1992.

They then headed to the building of the Moscow Soviet, where leaflets with statements from Yeltsin were posted. Kalinin and Boelstorff took one of the leaflets, but the quality was so poor that it was almost impossible to make out what was written on it. They decided to contribute to Russia’s democratic movement. In Boelstroff’s apartment, there was a Macintosh computer, a laser printer, and a photocopier, which they used to print the Tema newspaper.

The presence of such advanced equipment in the apartment made it one of the few serious printing presses that the coup leaders had not yet managed to shut down. Kalinin and Boelstorff reprinted Yeltsin’s slogans and made hundreds of high-quality copies. The next day, they went to the House of Government, where they began actively distributing the copies.

Dan Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Dan Healey, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

Tema magazine, #1 (1990)

Ty magazine, 1992.

Kalinin and Boelstorff printed hundreds of copies of Yeltsin’s slogans and actively distributed leaflets near the House of Government

That day, it became clear that the coup had failed. While it would be an exaggeration to say that the coup collapsed due to Kalinin’s efforts, many of those defending the parliament building were gay participants who had taken part in the conference held mere weeks earlier — a fact that both Kalinin and journalist Masha Gessen pointed out.

“I believe that thanks to the conference, they felt more empowered,” Kalinin explained the desire of homosexuals to join the resistance against the coup plotters. “We even considered issuing a proclamation on LGBT issues, but we decided it wasn’t the right time to draw attention to it, to highlight differences, or to potentially give the communists an opportunity to discredit the resistance.”

In December 1991, Boris Yeltsin, by then the president of the RSFSR, signed the Belavezha Accords, effectively dissolving the Soviet Union. The country began its reforms while Kalinin and other activists continued to send letters to the Ministry of Justice — and to Yeltsin — demanding the repeal of the article criminalizing consensual male homosexuality. Their efforts were supported by doctors, including Vadim Pokrovsky, a prominent Soviet epidemiologist and infectious disease specialist, who was actively involved in the fight against AIDS.

In 1992, Pokrovsky and his colleagues addressed Yeltsin with the following statement:

“We, the staff of the All-Union Center for the Fight Against AIDS, are sending you this appeal, the contents of which is dictated both by considerations for the further development of democracy in Russia and by the practical tasks of combating AIDS... We urge you, with your authority, to suspend the enforcement of the first part of Article 121 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR, which provides for criminal punishment for male homosexuality, and to facilitate its complete repeal...

The existence of this article in the republic is a peculiarity that distinguishes our country from democratic states... The existence of Article 121-1 complicates educational work [on AIDS prevention] and nullifies much of the work of our epidemiologists, while in the United States, the spread of the virus among homosexuals has practically been halted. We hope that our appeal will not go unnoticed and that it will receive a positive decision. By doing so, you will save thousands of lives. Thank you.”

Abolition of the article and the end of the active phase of gay resistance

Under mounting pressure from gay activists and the international community, Russian authorities were compelled to repeal the first part of Article 121. This change was quietly enacted on April 29, 1993, with little media attention. Lawmakers framed the legal revisions within a broader process of liberalizing the legal code, carefully avoiding a direct statement that homosexuality was no longer a crime. This cautious approach aimed to prevent potential public backlash, given the dominant homophobic sentiments in the country.

For many queer people, this marked a significant victory. The fear of criminal prosecution was finally lifted. However, with the repeal of the sodomy law, the active phase of gay activism and the work of MOLG effectively came to a halt. Roman Kalinin shifted his focus to the club business.

Despite this legal victory, the repeal did not resolve the broader challenges faced by Russian gays and lesbians. It did not guarantee equality under the law, particularly in the private sphere. For them, the fight for full recognition and equal rights was only just beginning.

Dan Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (Chicago: Chicago University Press).

Dan Healey, Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury, 2018).

Tema magazine, #1 (1990)

Ty magazine, 1992.