Upon celebrating its milestone 25th anniversary, the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum also reached a turning point in its transformation. Conceived as a platform for the exchange of opinions and informal meetings between the government and the private sector, the forum eventually evolved into a whimsical mix of a ruling party caucus and a collective therapy session. The participation of the Taliban and the heads of the Donbas quasi-republics further highlighted the ornamental nature of the event, which had long since outlived its usefulness anyway. The “Russian Davos” has completed its transition from the hope of domestic capitalism into a one-man show with fake adoration from the subjugated audience. The Insider covers the degradation of the nation's main economic fair in detail.

Content

«Bankers aren't thieves»

Riding the oil wave: the prosperous 2000s

Medvedev's reloading

Navigating the post-Crimean landscape

Reasonable fellas: the Taliban, pranksters, and the heads of Donbas «republics»

Once again in the spotlight: Putin's target audience

The Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) has celebrated its 25th anniversary. To be precise, the first event took place twenty-six years ago, but the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the jubilee forum edition coinciding with the war. By Russian standards, the event is stunningly resilient. Pre-Putin era initiatives that have survived until now retaining their formal characteristics are few and far between. The regime that centered its rhetoric on the formula “anything but the lawless 1990s” was doing all it can to sever all ties to that decade, but SPIEF was an exception.

The process of its transformation occurred at the confluence of multiple lines the Kremlin regarded as its priorities. The list of participants attests to the country’s international standing; the size of deals contributes to the illusion of economic power, and access to important foreign guests is a historically tempting opportunity for all ex-Soviet citizens. As a result, SPIEF turned into an Olympics or a world cup of sorts, a platform for boosting Russia's prestige in the conditions when the thirst for prestige had become unquenchable, with fewer and fewer peaceful ways to satiate it. On the one hand; the forum was an accurate representation of what was going on in the country; on the other hand, it resembled, though incomprehensibly, another 1990s relic – a Wheel of Fortune rip-off called Pole Chudes. The deeper you go, the more rituals and veneer you see, and the glossy cover pushes the content to the background.

«Bankers aren't thieves»

Admittedly, the initial concept was wildly different. In 1997, Russia was gunning for capitalism, having voted against Communists a year earlier and still oblivious to the impending default. Apart from established economic practices, the nation was short on respectable capitalists, businessmen with a positive image instead of an underworld vibe. To communicate with society, convey the impact on the country, and play an important role in its transformation, the business community needed a platform. An event promoted as the “Russian Davos” was designed to offer such a platform. In the 1900s, the World Economic Forum was a cult destination for the new Russia; in the public eye, the powers that be gathered in Davos to decide the fate of the planet.

“More Davos than a party caucus”, “St. Petersburg to become a new Davos?”, “A place where decisions are made”, “The forum confirms: bankers are not thieves” – this is just a handful of newspaper headlines covering the “Neva Summit” (an old unofficial title of SPIEF). Organized by Russia’s Federation Council and the Interparliamentary Assembly of the CIS, the event was said to have gathered over 1,500 participants from over 50 countries.

While the numbers may be impressive, no details were provided on the 1,000 allegedly signed projects that would define Russia’s future. The list of speakers was also nothing to speak of, by today's standards, because many of the announced speakers had declined the invitation. The forum had to settle for Federation Council chair Yegor Stroyev as the headliner, while the chief economic decision-makers of the country, including Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin and Anatoly Chubays, his deputy and the minister of finance, had better things to do. National media also paid little attention to the new forum – so little that Arkady Volsky, head of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, made a public appeal to the journalists to cover such meetings in more detail.

And yet, the forum's future centerpiece was already in place. Vladimir Putin, Deputy Chief of Staff at the time, made an appearance alongside his ex-boss, former mayor of Saint Petersburg Anatoly Sobchak. The event had already acquired another tradition that came to be its definitive trait – a penchant for luxury. Even back then, journalists wondered why discussions were crammed into a single day, while the remaining four days were dedicated to parties and receptions.

Looking back, you can’t help but feel amazed at Yegor Stroyev lauding the first forum’s apolitical agenda as its positive feature. Subsequent developments proved the Federation Council’s chair wrong in his assessment of the trend. However, his prophecy about the forum's bright and successful future came to be true. The event was declared annual starting from 1998, with an eponymous entity, St. Petersburg Economic Forum, tasked with its organization under the supervision of Herman Gref. In 1999, Boris Yeltsin charged the government with providing assistance to SPEF organizers, including funding. Prime ministers – Sergey Kiriyenko and Sergei Stepashin – no longer ignored the platform. Other high-profile speakers included State Duma chairman Gennadiy Seleznyov and Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko. The 1999 edition welcomed the first truly important foreign guest, Michel Camdessus – the Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (Russia still used IMF loans at the time). The total amount of contracts signed reached $4 billion that year.

Riding the oil wave: the prosperous 2000s

In the first years of Putin’s rule, when oil prices started their ascent, and the 1990s’ reforms gradually came to fruition, the forum was leaning more and more towards an efficient platform for economic debate. Speakers grew in numbers and credibility. In 2001, it earned the official title of the main economic forum in the CIS. The 2002 guest list included head of the WTO Mike Moore and president of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development Jean Lemierre. In 2004, the forum featured exhibitions and presentations by European nations. Dignitaries began to hold the forum in high esteem as well: the 2004 event brought together the prime ministers of Russia, Ukraine, and Moldova: Mikhail Fradkov, Viktor Yanukovych, and Vasile Tarlev, respectively.

The high profile of the forum presented an opportunity that was no longer possible to ignore, so Vladimir Putin joined the event for the first time as the head of state in 2005. Since then, the forum has been held under the presidential patronage and became an important item on the government agenda.

Presumably, it was then that the Kremlin was finally sold on the idea of SPEF rivaling the forum in Davos. Its title came to include the word “international”, with geopolitics slowly creeping in on the agenda (although this was true about the entire country). In 2006, the motto of the previous three years, “Efficient Economy – a Decent Life”, was replaced with “Globalization Challenges and the Competitive Advantages of Developing Countries”. Apparently, a decent life was postponed for later, once the top priorities had been dealt with. In the following year, which was also marked by Putin's Munich speech, SPIEF's motto was “Competitive Eurasia: a Space of Trust”. On the occasion, first deputy PM Sergei Ivanov made a futile promise to propel Russia to the world’s five largest economies before 2020.

At the 2007 SPIEF, Russia’s First Deputy PM promised to propel Russia to the world’s five largest economies before 2020

Medvedev's reloading

To date, Barack Obama's first term and Dmitry Medvedev's only presidential term still remain the golden age of the Russian economy. Their attempts to negotiate and foster a relationship between Russia and the U.S. were a short-lived and, looking back from 2022, erroneous strategy. The West offering its friendship was perceived by Moscow as weakness and carte blanche for preparing an expansion. In retrospect, SPIEF’s transformation at the time serves as an apt illustration of the bigger picture.

For one, 2008 ushered in a love for records. Medvedev's first forum set the bar in terms of funding (a record 720 million rubles) and the amount of contracts signed ($14.6 billion). The 2009 SPIEF was more frugal in view of the crisis, but in 2010 the organizers finally identified the optimal metric for reporting on the forum’s success: the number of agreements signed – an impressive 47 compared to 14 in 2007, going on 68 a year later, 84 in 2012, and so on. The forum budget grew as well, reaching 790 million rubles in 2010 and 880 million rubles in 2011.

Furthermore, SPIEF was becoming more and more of a social event. In 2008, Chukotka governor and Chelsea Football Club owner Roman Abramovich arrived in Saint Petersburg on his yacht and moored it next to the historical Aurora cruiser in the city center. Twenty other participants followed suit, traveling to the forum by sea on their private vessels. In 2009, another billionaire, Mikhail Prokhorov, gathered hundreds of SPIEF guests on the Aurora itself to watch a performance by rock musician Sergey Shnurov's project called Ruble, which took place on a nearby barge. Unsurprisingly, the media exposed the use of escort services at almost every SPIEF in the 2010s. Even without Instagram, which further highlighted this trend, escort girls posing as VIP guests’ dates were hard to overlook.

The forum still retained its nickname of “Russian Davos” by inertia, but any specific parallels were almost impossible to draw. Instead of meaningful discussions, the agenda was centered on milestone agreements. In 2010, the presence of French president Nicolas Sarkozy and minister of the economy Christine Lagarde earned Roscosmos a contract with the French Arianspace for the launch of carrier rockets from the Guiana Space Centre, while Gazprom struck deals with GDF Suez and EdF on the construction of the Nord Stream and the South Stream natural gas pipelines. Naturally, all the particulars of these contracts had been negotiated well in advance. Signing them at the forum was a way to showcase Russia’s economic might, while the appearance of Sarkozy and Lagarde emphasized the high profile of the event.

The largest contracts were the agreements between Saint Petersburg city administration with RusHydro and Sberbank to the amount of 65 and 60 billion rubles, respectively. In terms of ownership, two Russian state-owned entities – a corporation and a bank – contracted with Russian public officials at an international forum promoted as a practical tool for the business community to overcome barriers between Russia and the rest of the world. However, it only sounds absurd if you overlook the actual purpose of SPIEF at the time: window dressing for domestic economic achievements.

SPIEF essentially became window dressing for domestic economic achievements

This stage of the forum's evolution climaxed in 2013, the last sanctions-free year. Organizational expenses surpassed one billion rubles, the list of participants reached a record number of 7190, and the total amount of contracts signed bordered on an exorbitant $302 billion. Admittedly, the forum largely owed its financial success to the 25-year deal between Rosneft and the Chinese CNPC to the amount of $270 billion. Russia and China had signed an intergovernmental agreement on the matter as early as in March, but the contract was featured in the 2013 SPIEF statistics nonetheless.

Having regained his presidential post in 2012 and having crushed the protests against his reinstatement, Vladimir Putin donned the hat of chief innovator and idea generator. The rest could only speculate and exchange comments on the decisions made, refraining from any criticism. The head of state’s key SPIEF announcements included the merging of the Supreme Court and the Supreme Commercial Court, the bigger role of the state in state-owned enterprises, the establishment of the public ombudsmen institute, and the investment of the National Wellbeing Fund into development.

Navigating the post-Crimean landscape

The annexation of the Crimean peninsula, the proxy war in Donbas, and international sanctions halted Russia’s economic growth and development. Therefore, the Russian government had a different use for the forum in Saint Petersburg: to prove to the world that everything in Russia was in order, that economic isolation was a sham, and that the attempts to limit the country's economic weight were failing. In achieving this, no effort could be spared.

The sequence of records was a means to this end, with the number of agreements continuing its steady increase: from 175 in 2014 to 800 in 2021. The expenses and the number of participants followed the upward trend as well, reaching 3 billion rubles and 19,000 people in 2019.

The most notable foreign guest of 2014 SPIEF was Christophe de Margerie, chairman and CEO of Total (who would be killed in an air crash in Vnukovo outside Moscow later that year), but he only ranked 20th in the most quoted forum participants’ list. Apart from Putin – which goes without saying – he ranked below ten Russian public officials, eight state-owned enterprise executives, and the president’s personal friend Gennady Timchenko. The Russian political “elite” reveled in one another's company, engaging in self-consolation.

In the next five years – another stage of SPIEF evolution – the forum accounted for about a quarter of Putin's interaction with the world. At his phone-in sessions, Putin wore the mask of a kind, fair leader who can relate to the troubles of a common citizen. The large press conference was the opportunity to show that he had everything in the country (and in the world) under control – even though the differences between the two events have been fewer and fewer still lately. His address to the Federal Assembly underlined his capacity of a strategist, while SPIEF provided an audience for tales of Russia’s economic victories and its successful resistance to the West. Foreign presenters added a special touch, confirming the international, if not global, scale of the event at least formally.

Post-Crimean SPIEF provided an audience for tales of Russia's economic victories and its successful resistance to the West

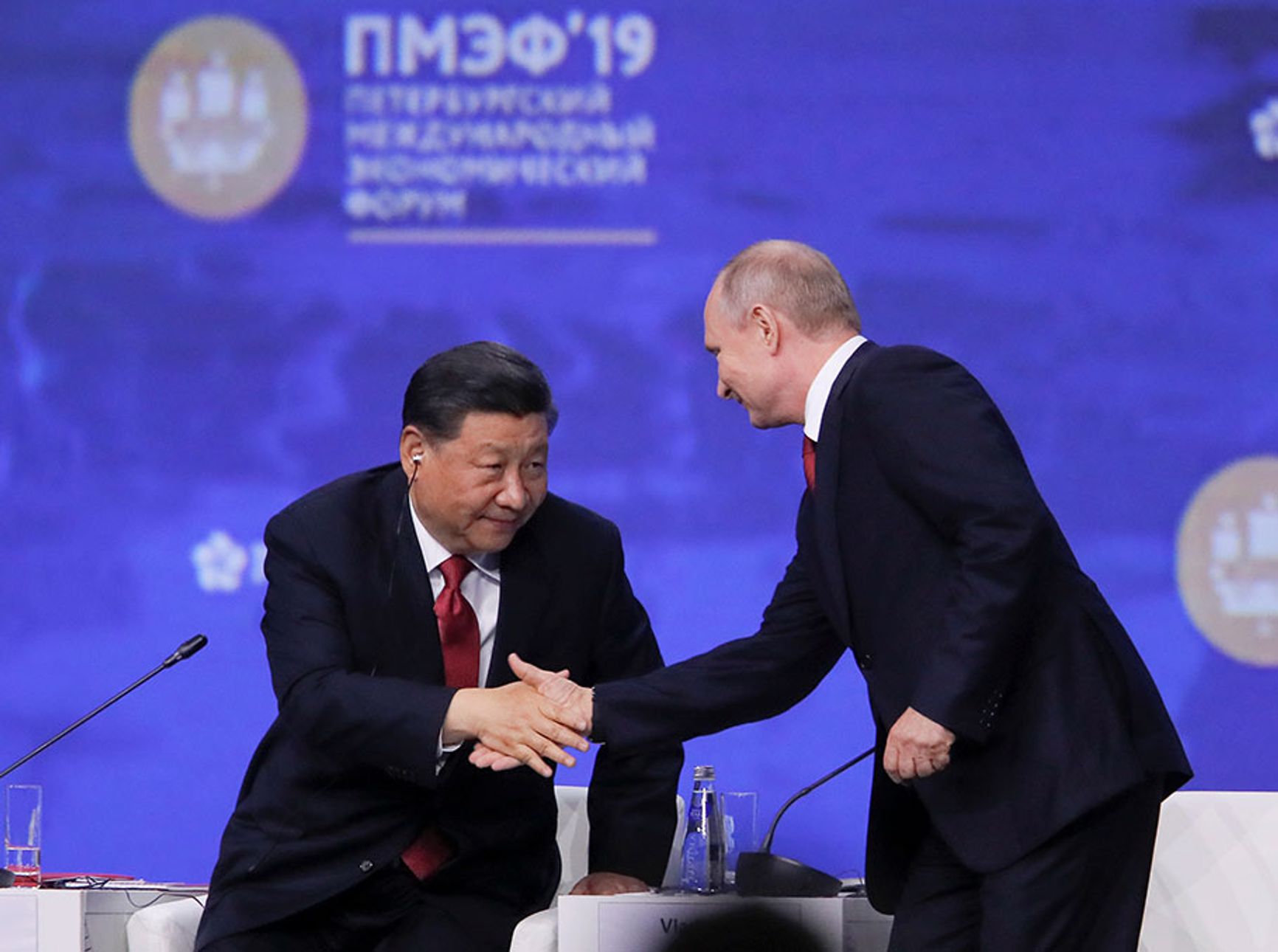

As part of the latter trend, the list of important guests shifted considerably towards Asia and the Middle East. In 2015, the forum welcomed Chinese leader Xi Jinping, as well as heads of Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, Mongolia, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Iraq. Subsequently, SPIEF's representative nature was secured by European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and his successor António Guterres, Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi, and his counterparts Narendra Modi of India, Shinzo Abe of Japan, and Peter Pellegrini of Slovakia, Bulgarian president Rumen Radev, and French president Emmanuel Macron, who appeared to have been among the last Western politicians to lose faith in reasoning with Putin. The presence of high-profile participants also legitimated the event. At the end of the day, high-level negotiations took place anyway but attending an economic forum in Saint Petersburg seemed less of a demonstrative gesture than an independent visit.

In other words, the format took shape and stabilized: Putin negotiates with foreign dignitaries, Russian civil servants, politicians, and oligarchs engage in public discussions on all things economic, and the number of large contracts timed with the forum serves as proof of its unfailing success. Similarly to the president's phone-in sessions and the annual press conference, a certain degree of dissent was permissible – to demonstrate the political establishment’s confidence in its power and ability to rebut any criticism.

Thus, in 2019, head of the Accounts Chamber Alexey Kudrin slammed the arrest of Michael Calvey, co-founder of Baring Vostok, as a shock to the Russian economy that doubled the outflow of capital from the country. To that, minister of finance Anton Siluanov responded that the situation had had no impact on the investment climate and had been getting more attention than it deserved. If we look at the forum's key takeaways, as per Kommersant, we will only find public officials and heads of state-owned enterprises on the list. No more questions were raised at their cozy get-togethers; the completely apolitical event lauded by Stroyev has become irrevocably politicized. Since public officials kept making their usual trite statements, the public’s attention shifted more and more elsewhere – for instance, to young female SPIEF participants who were taking a lot of selfies at stands but barely had anything to do with business.

Further on, the Prosecutor General's Office stand at the 2021 SPIEF raised few brows – and the surprise was more of a formality. After all, securocrats had gained considerable weight in the country's economy and thus deserved an exhibition stand. All the more so because Prosecutor General Igor Krasnov's statement was well-timed with oligarch Oleg Deripaska’s claim about the opposition undermining itself. Known for his straightforwardness and a proclivity for escort services, the billionaire reassured the audience that Russia was in for a decade of stability. For some reason, he also believed the new era would bring entrepreneurs to the forefront and usher in a new social contract.

Early in 2022, the social contract did change – although probably not in the way Deripaska had envisioned. This conclusion is further confirmed by the oligarch spending the first days of SPIEF out in the actual field instead of the forum's fringes: he published a video to that effect in his Telegram channel, with a voice-over reassuring that famine was not a threat. He made it to the forum for Putin’s – for fear of undermining himself, in all likelihood.

Reasonable fellas: the Taliban, pranksters, and the heads of Donbas «republics»

The war with Ukraine scrubbed SPIEF clean from its disguise. The force of inertia exposed the true objectives of the event to a grotesque level. The forum’s international status was emphasized by the Egyptian delegation, Kazakh president Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, who showed unexpected agency, and the main newsmakers of the first few days: heads of the Donbas statelets Denis Pushilin and Leonid Pasechnik and representatives of the Taliban movement. The status of international terrorists did nothing to prevent “reasonable fellas”, as Russian ambassador to Afghanistan Dmitry Zhirnov describes the Taliban, from making plans of fostering economic ties to Russia: exporting fruit and minerals in exchange for oil, natural gas, and wheat.

Out of habit, the organizers mentioned an impressive list of participants but refrained from disclosing it. According to our sources, many companies were hesitant of publicly admitting their representation at SPIEF for fear of sanctions or ostracism from the international community. As a result, public participation in the forum was the lot of those who had nothing to lose.

Day one climaxed in a discussion with MFA spokesperson Maria Zakharova, the puppet master of pro-Kremlin Telegram channels Kristina Potupchik (a SPIEF regular since 2018), and pranksters Vovan and Lexus, who advertised their most recent act – a practical joke on Joanne Rowling. Economically meaningful statements included a call by Anton Siluanov to get public officials to switch to Russian cars, a highly relevant proposal by presidential aide Maxim Oreshkov to scrutinize the authors of negative forecasts to identify possible enemies of the state, and the Bank of Russia’s idea to gradually lower the foreign currency share in private deposits.

Meanwhile, entertainment options included a space-traveling pack of sodium bicarbonate by the Bashkir Soda Company (which spent 200 million rubles on the artwork and its business lounge), coffee-serving android Dunyasha (loosely based on Miss Perm 2014 Diana Gabdullina, the wife of a local businessman), and the Rostov Region stand with Anton Chekhov, Peter the Great, and Karl Marx surrounded with musical instruments.

Once again in the spotlight: Putin's target audience

The first three days of the forum set the stage for Putin's yet another historical speech anticipated by state-owned media as nothing short of the declaration of a “new world order”. In fact, his address was a blend of second-hand statements and ressentiment: a mixture of his grudges against the West, his hope for support from friendly nations, a faith in his power, the imminence of his success, and a traditional reference to Russian history.

“Russia and its efforts to liberate the Donbas have nothing to do with it. Today's price growth, inflation, shortages of food and fuel, petroleum, the generally troubled energy sector – all of these result from systemic errors made by the current U.S. administration and European bureaucrats in their economic policies,” the Russian president insisted.

According to Putin, the West is fully responsible for the food and energy crisis, which was caused exclusively by the sanctions, and the war in Ukraine has had no economic impact – as he underlined multiple times. The EU has lost its agency and is doing the USA's bidding; Russia is open for cooperation with all willing parties; its society is consolidated like never before; its goal is not to replace import but to develop the world’s leading technologies. He also made a few promises: to lower subsidized mortgage rates, to abolish state inspections for Russian businesses, to review incarceration terms for economic crimes, to comprehensively modernize the public utility sector, and to improve life quality in rural areas.

“The recent events have further illustrated my earlier statement: home is always safer. Those who turned a deaf ear to this self-evident truth lost hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars,” the Russian leader claimed.

It was impossible to ignore that, having spoken for over an hour, Putin failed to mention, even in passing, anything about China, the USA’s main economic rival. Given that Xi Jinping addressed the forum participants remotely immediately after Putin, such an omission eloquently attests to Putin’s frustration. China's assistance, which Russia has been relying on lately, is stalled, and unexpectedly so. Technologies, communication equipment, plane parts – China remains evasive across all of the key sectors.

Putin is evidently frustrated at China stalling its assistance

During discussions, Putin was also shocked to get the cold shoulder from Tokayev, whose name he had never learned to pronounce correctly. Not only did the president of Kazakhstan announce his lack of intention to recognize the independence of the DPR and LPR, but he also scolded the Russian deputies and journalists who had taken the liberty of making inappropriate statements about his country. It is no secret that he was addressing, among others, Tigran Keosayan, the husband of propagandist Margarita Simonyan, who was moderating the exchange. The host of the forum had barely expected the Kazakh leader to reprimand his pocket journalists in his presence.

It is hard to pinpoint the target audience Putin had in mind for his address. He was barely looking to reach Western leaders: if the U.S. is an enemy and the EU is its sycophant, what is the point of reasoning with them? Neither was he addressing the Russian people: for that, the focus on the war was insufficient, and the matters of social importance were touched upon too briefly. His call on the business community to invest into Russia sounded like déjà vu – as though he had borrowed it from earlier speeches. His sovereignty rhetoric included an explanation that without sovereignty Russia would have to sell saddles. He did not specify who would be buying them in the 21st century.

In all appearances, pronouncing this speech, Putin was mainly addressing himself – and history at large. He was trying to reach the generations to come, who would watch the leader’s speech on RuTube and appreciate his wisdom and foresight. For now, the applause from the floor reassured him nothing terrible had happened; that he still had a bright future ahead, and that the wheel of history would make another turn, making Russia great again. The train “party caucus – Davos – party caucus” has reached its final destination.