Having released multiple groups of former prisoners, Wagner Private Military Company (PMC) founder Yevgeny Prigozhin joyfully claims that they are reformed fighters who atoned for their sins on the Ukrainian front. He adds that they have become full-fledged citizens – heroes who have honorably returned home to their beloved wives and mothers with handsome sums of money.

But reality is very different from the picture painted by Prigozhin, judging by the online chats of those very wives and mothers. The women that have waited for their partners from prison and war speak of the violence and cruelty of those who have returned. Those who are still waiting are struggling to secure payments from the “Wagner accounting office.” They learn about the deaths of the mercenaries when they stop receiving their paychecks, and then the search for their graves begins by looking through names on cemetery crosses. To avoid paying funeral fees, the PMC does not inform the women about their partners’ deaths.

How do Wagner mercenaries’ relatives find out about their deaths?

Most often, the relatives of the prisoners enlisted in the Wagner Group, find out about the deaths of their loved ones from anywhere but the PMC. There are several ways to find out if one’s relatives are still alive. The first way is asking for help from online groups working to find prisoners fighting in Ukraine. One of these closed groups on Telegram has 477 members, most of whom are women. Frequently, they only find out about the deaths of their relatives when they stop receiving their paychecks. Before being sent to war, men recruited by the Wagner PMC sign a power of attorney in the name of their loved ones so that they can receive payments instead of them. When the mercenaries die, the relatives stop receiving the funds. In this case, the PMC does not inform anyone about the death of the soldier, and their relatives have to confirm the death on their own.

“After the death they have to pay the funeral fees, as well as help the relatives to cover the costs of burial. But, judging from the stories of women whose stories I read in the chat, the state often hides the deaths of relatives in PMCs, and their status remains unconfirmed. This allows them to avoid funeral payments, and they even stop paying [the soldiers’] wages. That means they’re aware of their deaths,” a relative of one of the dead prisoners told The Insider.

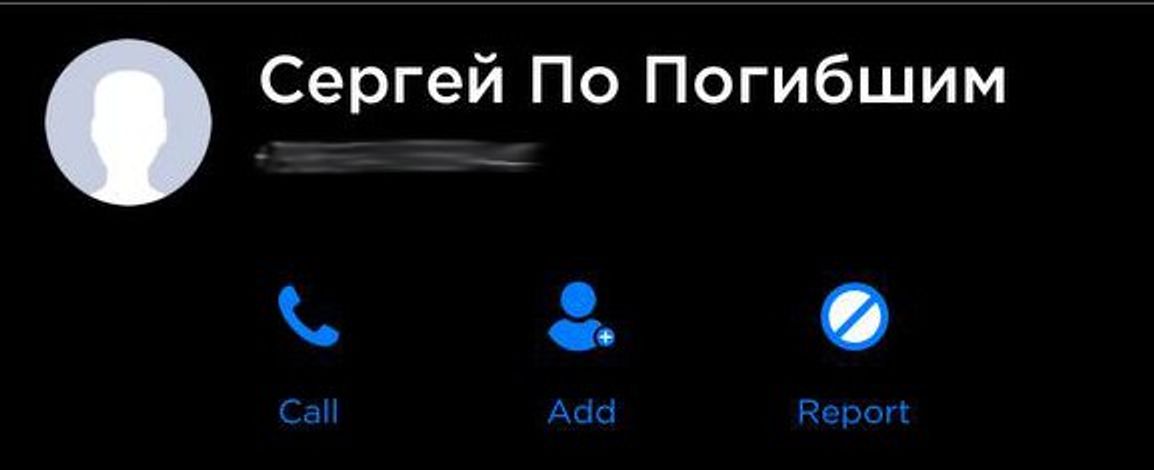

If one asks members of the group how to find out about the condition of a family member at war, or get an answer to a salary-related query, you are likely to be redirected to someone named Sergei. The group members also call him “Helpdesk” or “Service 200” [The number 200 is used as code for the dead in the Russian military – The Insider]. His number appears in the app GetContact as “Sergei About the Dead.” In the databases, the number is listed as belonging to Sergei Viktorovich Rakitin or Andrei Olegovich Beker and registered in Russia’s Krasnodar region. Both Rakitin and Beker are listed in Ukraine’s Myrotvorets database as members of the Wagner PMC. Beker's profile states that he had a conflict with a bank over his actions with money, which the bank qualified as fraud.

A GetContact entry listing "Sergey About the Dead"

Sergei reportedly has access to the lists of the dead and is supposed to help in the search for relatives. In fact, judging by the reports of the women in the chat rooms, Sergei is far from reliable, as he may not reply or pick up calls for up to two months, with his replies often amounting to a one-word “wait.” “Sergei” also did not respond to a message written by a correspondent from The Insider, written on behalf of a recruited prisoner’s daughter.

Another way to find out about the death of a relative is to check the Wagner PMC’s cemeteries, as the mercenaries are often buried there, not only without funeral services and other rituals, but without even informing their relatives. At the beginning of the year, a cemetery with 27 graves decorated with wreaths bearing the Wagner PMC logo appeared in Mavrino near Moscow. “The only thing we can assume is that they are Wagner mercenaries. We were advised not to get involved. So far, none of their relatives have approached us. They showed up in January. I'm not here all the time. They could have come earlier, too,” a priest from a local church told news website MSK1.ru.

How are the mercenaries’ relatives (not) paid?

To get paid by the Wagner PMC, one must not only call the group’s “accounting department,” but also physically retrieve the money, as the mercenaries are paid exclusively in cash.

“If the prisoner signed a power of attorney [over to a third party], their representative will be called – usually within a month – to specify in which city they want to receive the money. Then the cashier calls and calls them to collect the money. Cash only. If you miss the cashier's call, the paycheck is carried over to the next month. If there’s no power of attorney and the fighter did not come back alive, then the salary will be received by the one in whose name a will is written. Everyone has to write one. A month's pay is issued after the 20th [day] of the following month,” writes one of the relatives of the enlisted prisoners in a chat room.

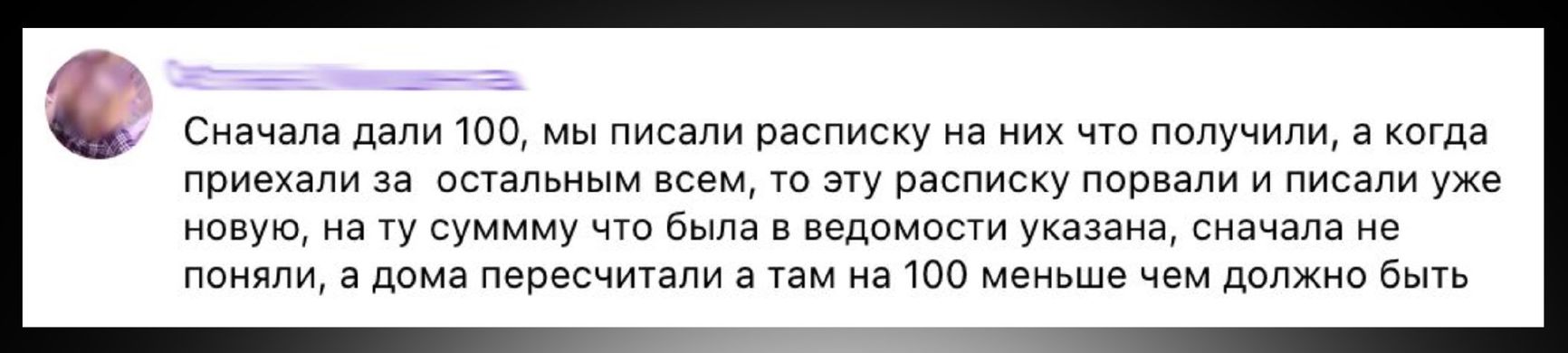

In order to get additional payments for a dead mercenary [often referred to as “coffin money” (“grobovye”) in Russia – The Insider], the relatives of the enlisted prisoners need to contact a “curator.” The relatives themselves do not use the word “coffin money” (“grobovye”) – only “funeral money” (“pokhoronnye”). More often than not, issues arise with obtaining these funds as well. Sometimes, as in the case of “Sergei,” the relatives of the dead are given promises, which are very reluctantly fulfilled. People are even sometimes deceived – one woman in the chat room claimed she received 100,000 roubles (approximately $1,200) less for her husband's funeral. In some cases, relatives living in Russia’s regions have to travel to the nearest town that has a “cash register” (the nickname likely used for the Wagner PMC’s payout centers).

Berating the Russian Defense Ministry, which does not supply the Wagner Group with artillery shells, is fairly common in the relatives’ chat rooms. However, the founder of the PMC, Yevgeny Prigozhin, is respectfully called “Yevgeny Viktorovich” and praised – despite the issues with payments and informing relatives.

How do the mercenaries return to Russia?

The chats discussing the mercenaries’ return – or failure to return – from the front line are also. Grieving women rejoice if their husbands remain alive, and omit details of their biographies. The women try not to talk about the fact that their partners killed people in Ukraine. Many write about “defense of the Fatherland.” Those who bring up the ex-convicts' pasts are quickly silenced by other women. One of the dialogues read:

- A murderer was released in [Yekaterinburg], [he] works as a security guard at a mall. That's what the girl above wrote about him. What can I expect from him? How did he get that job?

- I read your comment and I don't quite understand. What do you care about that security guard? Especially since he’s already redeemed himself. There's no need to accuse anyone of anything bad in advance.

For most of the relatives, the mercenaries recruited in the prison seem to be victims of circumstance. However, after their return, the men often begin to live the same life that led them to prison in the first place. Relatives of former prisoners write about their issues with alcohol, deviant behavior, and even substance abuse overdoses.

The recent story of Ivan Rossomakhin, a resident of the village of Novy Burets, stands out among these cases. In 2020, Rossomakhin was sentenced to 14 years in prison in a maximum-security penal colony, but was released two years later with the help of the Wagner PMC. After returning from the war, Rossomakhin terrorized his native village with violence and death threats, and then became the main suspect in local woman’s murder.

Almost a month after Rossomakhin’s detention, the Russian online database “Pravosudiye”, which contains an archive of judicial acts, contains no record of a court hearing on his arrest, although the formal terms of his detention by the police have long expired. The old court decision that initially sent him to prison, where he became a member of the PMC, is available in the database. One can conclude that either the court ruling has not yet had time to appear in the system, or Prigozhin has indeed kept his promise, and Rossomakhin has been taken back to the front line taken by Wagner’s “recruiters.” Prigozhin alleges that there are very few cases of re-offending by prisoners that have returned from Ukraine – only 0.31% of ex-convicts that have come back from the front lines have committed crimes, claims the Wagner Group founder.